Vegetables waiting to be chopped, a tower of vessels waiting to be scrubbed, stinking leftovers in the garbage and a perpetually leaking sink – the Great Indian Kitchen succinctly describes so many women’s reality through the story of a newly married NRI woman into an orthodox and patriarchal family that systematically smothers her dream of being a dance instructor. She is expected to spend all her time in the kitchen, attending to the needs of the men in the home — a narrative that’s lived experience for millions of women. If women are expected to spend time in the kitchen, why is the space designed so poorly?

My interest in looking at kitchens started during the COVID-19 pandemic when we were forced to stay in our homes. I decided to assist my mother and cook one meal a day for some days of the week. I felt physical discomfort in the enclosed space, something that my mother didn’t seem to mind or had simply gotten used to; I had to take breaks.

This made me curious about those who handle the kitchen, who are subjected to this discomfort daily. This then led me to questions such as how the kitchen was designed, what the connection is between social relationships, everyday gendered practices, and experiences of inhabiting a kitchen in different housing typologies and spatial configurations.

My study encompassed observing kitchen spaces in a bungalow, a three BHK apartment, a tribal house, a one-room kitchen apartment and a slum. The observation was that the space produces certain types of relationships between different members occupying it. Sometimes, the person there does not get help due to the lack of interest from other members of the family. While this may prove to be frustrating to the person who has to spend her entire day in the kitchen, it is also possible that they claim the entire place as their own, where the kitchen functions as more than just a space for cooking and opens up the possibility of it being a prayer room, living room, a place where one can carry out their hobbies.

A typical kitchen is designed for one or two people to occupy and undertake various tasks throughout the day but their opinion is rarely considered while designing the space. For example, in the case of the tribal house, a woman pulls the kitchen outdoors to make it easier for herself. This also allows multiple people to assist her which is usually not the case in a closed kitchen in an apartment type .

My thesis opens up ways in which different kitchens have been configured across various types and questions the existing norms that go into the design of the kitchen

Pushed aside: Enclosed apartment kitchen

On the 24th floor of a building in Hiranandani Gardens, Powai, Pooja Joshi’s day starts at 7.30am to prepare tea and breakfast for her husband, Arun, her mother and herself. A small phone holder placed on the kitchen counter indicates that recreational activities merge into the kitchen space — she watches YouTube or scrolls through Instagram while cooking. The kitchen is surrounded by walls with very little natural light and ventilation. It is completely closed off, by the partition walls, from the rest of the spaces in the house.

Pooja’s routine revolves around family members – Arun leaves for office at 9.30am, she readies herself, wakes up her 11-year-old daughter for school, does domestic chores, watches a few videos if she finds the time in between, serves the daughter lunch and packs her tiffin for school, sits at the dining table or in the master bedroom, chats with her mother and serves her reheated lunch by 2pm by which time her domestic help has come to clean, naps, then returns to the kitchen to make the evening tea and spends most of the evening cooking dinner for the family. Arun returns from office at 9pm and lies down on the sofa, where he scrolls through his phone or watches the TV. Pooja attends a numerology class between 9pm and 11pm. On some days, Arun waits to have dinner with Pooja while on other days, he eats with his daughter and his mother-in-law assisting the latter to get the dinner to the table. Post the class, Pooja has dinner and the couple talk to each other about their day.

The kitchen in their home is always occupied by the women of the household, mainly Pooja, where they spend most of their day. Since the kitchen is closed off, it allows women to completely take over the space of the kitchen, where the other activities and hobbies start to blend in with the activities of the kitchen. While doing domestic chores, she makes space on the kitchen counter to place her laptop and attend classes, receive phone calls, or watch videos. It also seems to deter others from partaking in any kitchen activities, either due to lack of interest or through design itself. She arranges the kitchen in a way that it becomes convenient for her to carry out these tasks while doing daily domestic chores.

Supporting social dynamics: Open-plan bungalow kitchen

Radhika Sharma resides in a bungalow located in the Shimpoli Village in Borivali suburb of Mumbai. It is a State Bank of India colony. A busy main street is connected to the quiet inner street which has various bungalows. Radhika’s bungalow is a G+3 structure protected by a large main gate. Her family consists of her grandparents, parents, and her brother, all living together. All the floors of the house are connected by a lift or a staircase.

Each floor is assigned different functions which, in turn, influences the way everyone inhabits the house. The ground floor consists of store rooms, a large gathering hall, and a theatre room. The hall is only used when there is a party happening. The family has hired two men as gardeners and one man as their domestic helper. He stays with the family and resides in the gathering hall. The first floor consists of the living room, kitchen, dining room, library, and drafting space. The kitchen layout is that of an open kitchen which looks into the living space and is separated from the dining via an island counter.

The family wakes up around 6am. Every person in the family has an individual room or corner on different floors. They meet in the dining space for tea, breakfast and talk. Radhika’s father and her grandmother are very fond of cooking, so they prepare the morning tea and breakfast for everyone in the house. The small island counter makes it easier to serve food. This type of kitchen layout allows multiple members of the family to participate in the kitchen.

The first floor is largely occupied by domestic help and the family cook. The family runs three businesses, Radhika’s father and her grandparents work, whereas her mother is a mandala artist. Sunita, the family cook, comes over at 9am. She helps in the kitchen and prepares lunch for all the members of the family, as well as for the employees of the family business. Most family members are not present in the house for a large part of the day. This allows the first floor space to belong to the cook and the domestic help, where they are able to have a chat, without having questions asked. Sometimes the family sits in their garden area and spends time together, or they spend that time in their respective bedrooms. The day ends with all of them sitting in the theatre room, watching a movie together.

Facilitating interactions: Outside tribal home kitchen

Mandadini Sapte lives in a tribal house, located in Navpada, Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Borivali. She moved here two years ago when she got married. It was renovated recently to have the kitchen inside so that a gas stove could be installed. However, there is a larger functioning kitchen outside the house which has a chullah and a large number of wooden logs next to it.

Her day starts at 4am, she does domestic chores, prepares breakfast and lunch for her family members, and then leaves for work at 7am. She works as a domestic helper at Kajupada nearby. She returns by 11am to help her younger daughter get ready for school. Her older son also works as domestic help. Her husband used to be a gardener in the National Park. The sole earner of the family, she invested in renovating the house.

She preferred to have the kitchen inside because she finds it difficult to cook in the outdoor kitchen during the monsoon season. However, the larger outdoor kitchen allowed her to sit down and work on the chullah. She prepares dinner at 6pm as it becomes difficult to cook in the dark. While cooking in this kitchen, she moves out to chat with her neighbours; they collect wood logs together or even wash the utensils together. The outdoor kitchen helps to generate a social space, where the woman is able to ‘get out of the kitchen’ and interact with neighbours. Since the space is not constrained, other women of the family can come to help too.

Despite having a kitchen with a gas indoors, she is scared to use it; she is accustomed to the chullah. The family is often visited by Shama, Mandadini’s sister-in-law, who takes turns in the kitchen and chats. During festivals, other relatives visit them; they all stay together and eat together in one house. Mandadini finds her new indoor kitchen closed off and too small, making it difficult for her to store essential items. She uses a small corner of the large living space as her storage. She plans on adding partitions within the living space to segregate the kitchen. In this way, she also has the freedom to change the layout of her kitchen and make it larger.

Storehouse over kitchen: One-room apartment

Varad Nagapurkar and Himanshu Wagh moved from Nashik and Nagpur respectively to pursue CA, and now live in a one-room kitchen apartment, in a cooperative housing society, located on Currey Road, Lower Parel. The location is convenient as they work nearby. Their day starts at 7am and they spend two hours in the morning studying. Their room consists of two beds, a clothes hanger, and a study table to place their books. The kitchen is used entirely as a storage space; the kitchen counter holds all the daily objects. There are some utensils placed on the table, but no gas connection. Due to space constraints, they store their luggage in the kitchen as well.

They have breakfast at the nearby street stalls. Both are provided lunch at their offices, so their kitchen is not frequently used. Their busy work schedules make it difficult for them to cook for themselves; they are also not keen on cooking. Both usually return at 8pm and dinner is provided by their neighbour upstairs. They clean and reorganise the kitchen counter over the weekends.

Here, in a home occupied by two working bachelors, the kitchen ends up being a storage room. Since their lunch is provided for by their respective offices, or bought from shops, and dinner obtained through a tiffin service, there isn’t much use for the kitchen. This then opens up the idea of the kitchen being the city or the city as the kitchen, where one travels through the city for daily meals.

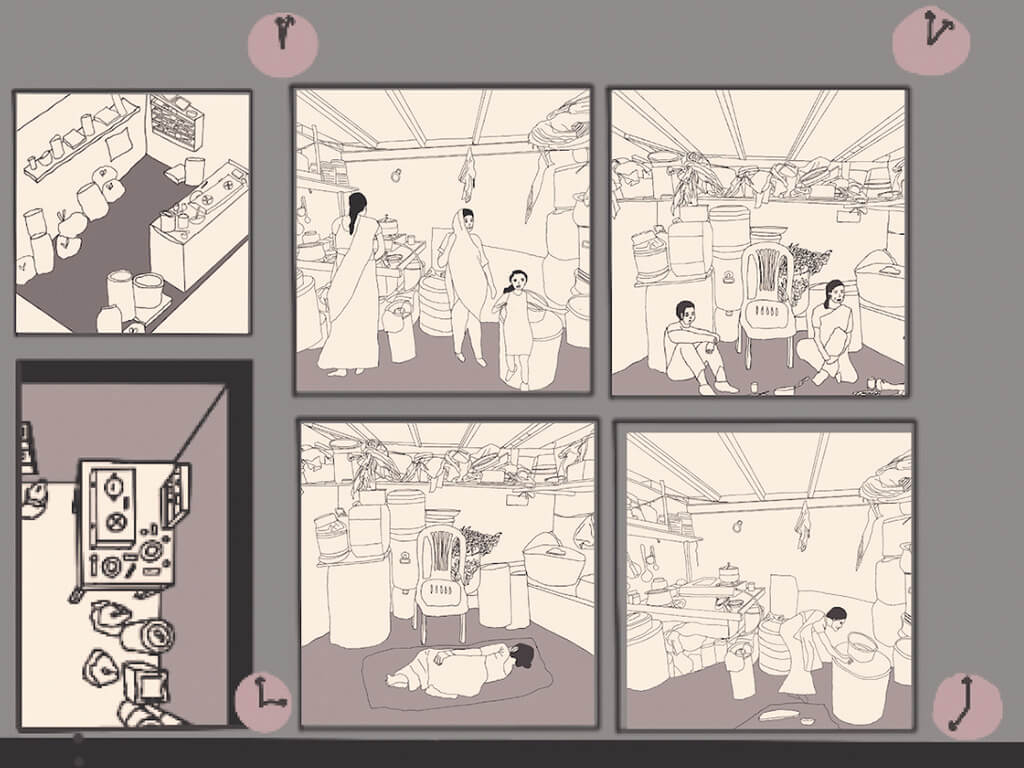

One-woman operation: Settlement kitchen unit

Meandering through a landscape of metal scraps and stacks of newspapers, Daarukhana in Mumbai has large warehouses made from different ship parts. Kolsabunder here is a finger-like projection into the water. One edge of this has boats and ferries docked for repair while the other has informal settlements that form the edge of the land. Najeebunissa, a resident in the settlement, has a three-room house with 11 family members, including in-laws, husband Nizamuddin and five children.

Nizamuddin’s father had purchased one unit 40 years ago; the family expanded their home by purchasing two more units, one adjacent to the first unit and the other above it. One of these units functions as the kitchen. Najeebunissa and her mother-in-law spend most of their day here cooking for the family. The kitchen is a low and dark place; the only source of light is the open door. The common wall between the living and the kitchen has an opening the size of a small window that is used to serve food. The kitchen is organised with various utensils placed on the ground, metal shelf, and on the wall.

Most of the ground space of the kitchen is taken up by large blue water drums. The women wake up early to cook for the children and husband. Najeebunissa’s two daughters are school-going children while three sons are working; one of them is married and lives away. In the kitchen, Najeebunissa often gets exhausted. A chair is placed to allow her to rest. She talks about making changes to make it more comfortable for herself such as getting rid of the water bins, making more space in the kitchen, and adding shelves to store utensils. Only occasionally, her children use the kitchen to cook their favourite dishes. With the kitchen here being one unit, functioning when the men leave for work, it also allows for the space to be taken over completely by the woman who is largely responsible for all domestic chores.

Gendered practices and their spaces

As one of the most frequently used and essential spaces, the kitchen of any home influences how different genders move and behave in the house. Through these case studies, this paper maps how the space of the kitchen influences hierarchies in the household, the kind of social spaces generated, and how the efficiency of the kitchen influences an individual and the social spaces that get produced.

By mapping five households of different scales belonging to people of different socio-economic classes, a genealogical shift in the kitchen form across various types was observed. Upon analysing the different cases, the configuration of the kitchen played a large role in how different members of the family contributed to the space of the kitchen, as well as how different classes of people occupied the space.

A prominent shift observed was how the size of the kitchen changed to “increase” the efficiency of an individual who occupied the kitchen. A kitchen located outdoors as opposed to a restricted kitchen in an apartment type, encourages social interaction among individuals and their neighbours. In the apartment, the kitchen becomes a “confinement” which compels an individual to remain in that space. However, this confinement can also allow her to make the space her own and have a sense of authority over it.

This research also looked at different ways in which the kitchen is occupied and could possibly be used in ways other than its utilitarian purpose. It opens up ways of seeing the kitchen as a private space where the woman can have her privacy. It also becomes an extension of the house, allowing one to meander through both of them freely. The configuration of a kitchen allows it to become a social space, where a large number of people can gather and interact.

The city, in so many ways, opens up as a kitchen too, especially for people who frequent it.

Prishita Kulkarni, a final-year student at the School of Environment and Architecture, Mumbai, is interested in exploring spatial and social dynamics in domestic spaces through a gender lens – this essay is a part of her final year academic thesis. In her free time, she enjoys experimenting with make-up and hair dye, and makes sure to try a variety of cuisines when she travels.

Photos and drawings by Prishita Kulkarni