The Lalbaug flyover is one of the oldest in Mumbai. At its southern end, towards Byculla, is situated the city’s old zoo and botanical garden. Few know of the latter even though the Veer Jijamata Bhosale Botanical Udyan, a vast expanse of green spread over 60 acres in central Mumbai, has quietly cleaned the air in this densely-constructed erstwhile mill and port area. Popularly called Rani Bagh, it is also Mumbai’s priceless crucible of biodiversity with rare species of flora. The botanical garden had, at the last count, over 4,130 trees of 256 species which is nearly 80 percent of all tree species found in Mumbai.

Between its two gates stands the clocktower gifted by philanthropist David Sassoon in 1864. An east-west radial plan leads to the botanical garden where two old Baobab trees, on either side of an ornate arch, offer a welcome. With several internal gardens, wide connecting pathways between them, and historical structures, the botanical garden is a Grade II-B heritage precinct. Originally established in Sewri in 1860, it was shifted here and opened to the public in 1862. And has, since then, quietly served the city.[1]

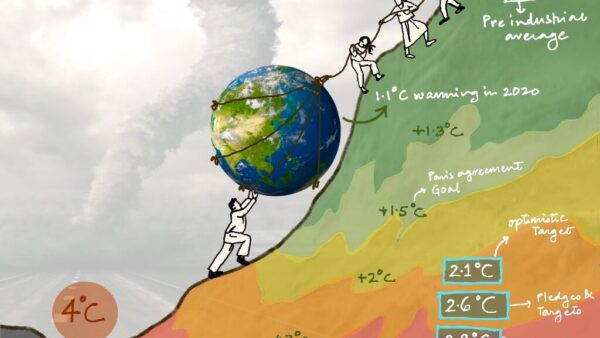

However, the build-more syndrome in Mumbai meant that the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), its custodian and caretaker, decided to redevelop it in 2007-08 as a ‘world class zoo’ with constructed enclosures for new animals, amusement centres, fine-dine restaurants with a view of cheetahs, a night safari, and zones depicting life on the African and Australian continent including a Gondwana land section.[2] This, pencilled nearly five-six years later into the Mumbai Development Plan 2034, would have spelt the end of the city’s green lung and botanical wealth.

Photo: Suditi Gupta

Many were horrified. A group of women decided to turn their angst into a campaign to save it. Hutokshi Rustomfram, Shubhada Nikharge, Sheila Tanna, Hutoxi Arethna, and Katie Bagli came together as trustees of Save Rani Bagh Botanical Garden Foundation. Rustomfram used to edit a law magazine, Nikharge was a banker, Tanna is a practising ophthalmologist while Bagli is an author and Arethna was a school teacher. They came from diverse backgrounds but were united by their passion for trees.

Gradually, they got support from organisations like the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), WWF-India, Sanctuary Asia, National Society of Friends of the Trees, NAGAR, Awaaz Foundation, Urban Design Research Institute (UDRI), Oval Trust, Indian Heritage Society, and, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

If the Rani Bagh stands secure today, Mumbai has this group of indefatigable and persevering women to thank. They mounted awareness campaigns, conducted nature and heritage walks there, made audio-visual presentations, filed RTI applications, trawled through the labyrinthine maze of offices and permissions, travelled to Delhi to meet senior officials and more – all detailed, painstaking and tedious work. It paid off, slowly.

Photo: Suditi Gupta

Their fight

The group’s intent to fight back began at the most basic level: to obtain a copy of the redevelopment plan. Their RTI applications yielded nothing until an anonymous do-gooder, perhaps moved by their effort, dropped it off for one of them. “When we saw it, it took our breath away. It was much worse than we had imagined,” says Rustomfram, “It would have flattened and decimated the botanical garden and its trees, and obliterated its heritage layout.”

The BMC had proposed a Rs 434-crore budget for the redevelopment but the women figured out that it did not have the required permission from the Central Zoo Authority (CZA) and the Mumbai Heritage Conservation Committee (MHCC). This gave them elbow room to mount campaigns. Two of them, Rustomfram and Nikharge, travelled to Delhi to make a representation to the CZA. The permission to construct was granted but their efforts had yielded the clause “without touching a single branch or creeper”.[3] The group approached the MHCC as well as the then union minister of environment and forests Jairam Ramesh.

A tip-off that a cement mixing plant would be installed on a plot acquired for Rani Bagh’s expansion made them appeal to the Zoo Authority to review its permission. RTI applications showed that the authority had appointed a committee whose report stated that at least 200 acres would be needed for the redevelopment while Rani Bagh stood on much less. The women went back to the MHCC with this and photos of trees dying due to the cement plant. “You don’t need to cut a tree to kill it,” says Rustomfram.[4] That remark resonated with MHCC members.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

‘Not’ a botanical garden, says BMC

Surprise awaited the women. The BMC submitted a report to MHCC in 2009 stating that Rani Bagh was not a botanical garden.[5] In a ten-page email letter to them, an additional municipal commissioner lashed out that they suffered from the ‘CAVE’ – Citizens Against Virtually Everything – syndrome. This meant they had to first prove that Rani Bagh was a botanical garden – to its custodian and caretaker.

History and personal networks came into play here. They divided the work. Some dug into newspaper archives, others into the Minutes of meetings of the erstwhile Bombay Agri-Horticultural Society at the Townhall. Yet others pored over old master plans and maps, or looked for tree surveys over the decades. Some surveys did not even mention the rare trees of Rani Bagh. What was not recorded can be easily erased, or so the BMC thought.

“What I studied for Rani Bagh was more than what I studied during my formal education,” says Nikharge. Their RTI applications simply yielded files; they had to go over pages upon pages to ferret out information. In the archives of The Times of India dating back 150 years, Nikharge recalls that the person in charge helpfully told them to look for ‘Victoria’ to find information about the garden. “To our dismay, we discovered that, back then, Victoria was to India what Shivaji Maharaj is to Maharashtra. Every other place carried her name, it appeared two-three times on every page,” recalls Nikharge, reminiscing about the yellowing pages behind smudgy glass.

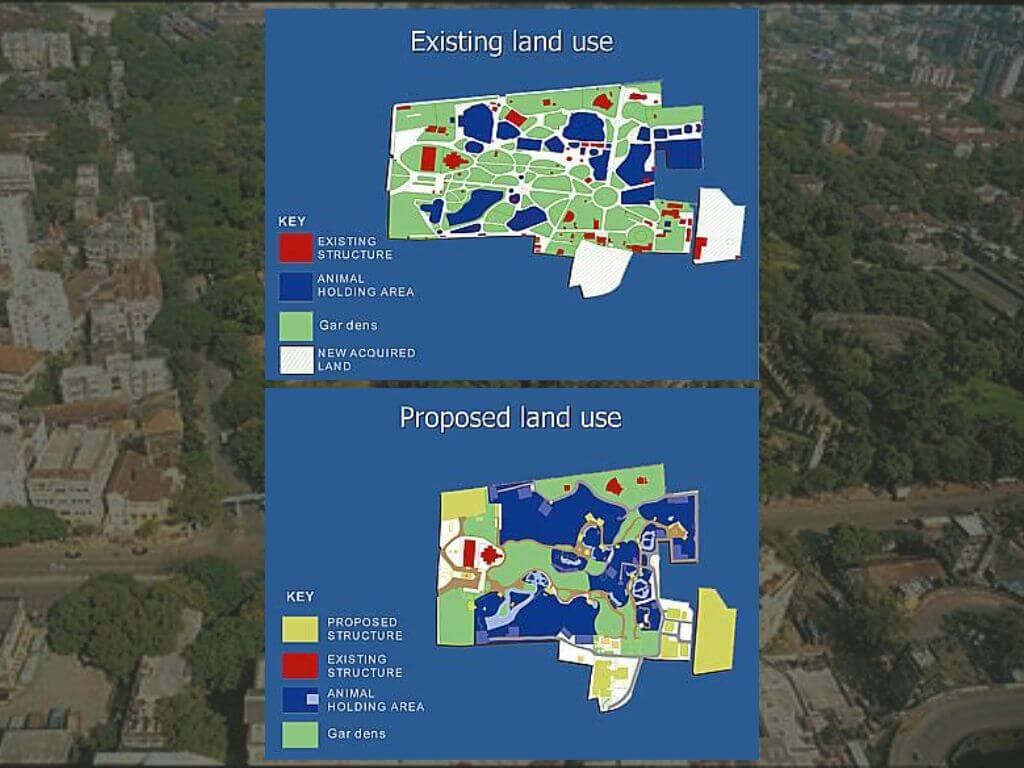

Eventually, a fresh survey ordered by the MHCC and conducted by renowned botanist Dr Marselin Almeida showed the existence of various species of plants.[6] Its authenticity as a botanical garden was, finally, established; it was later notified by the Maharashtra government.[7] In March 2011, the MHCC ruled that renovations should not disturb the botanical garden and the pathways.[8] Undeterred, the BMC redrew the plan six months later; though the pathways were unchanged, earmarked ‘service areas’ would make the garden inaccessible. If realised, it would have reduced the pathways from the existing six to two kilometres too.[9]

Source: Save Rani Bagh Botanical Garden Foundation

Source: Save Rani Bagh Botanical Garden Foundation

It took a city to save a garden

The women of the Rani Bagh Foundation found help coming their way from known and unknown quarters. For example, at the MHCC, a gentleman asked them about the footfall in the garden which was an average of 8,000 a day but would go up to 30,000 on holidays.[10] “That might mean a stampede; the security issue could be cited to restrict numbers,” he said. They worked on that aspect.

The undeterred women met, in all, five municipal commissioners and seven additional municipal commissioners, diligently pursuing appointments when new officials took over. After one such meeting, as they walked out, a peon ran to them and without a word handed them a bus ticket. “The back of it had a phone number,” Nikharge recalls, “When we called, someone told us that debris was going to be dumped in an internal garden. Because we were forewarned, we could get it removed.”

Tanna says that Mumbaikars pitched in with support through contributions, online petitions, and open letters to officials. “Nature lovers and environmentalists posted our plans and ideas on their groups which helped,” she says. This was crucial as the women focused on representations and official meetings. It helped that DM Sukhtankar, the then chairperson of the MHCC, was convinced that Rani Bagh needed to be saved.

“It has some unique features and species of trees, and serves as an important lung of the city,” he said to Question of Cities, “unfortunately, those in charge have given precedence to the existing zoo though the botanical garden is older. It is not a question of which is more important but while the importance of one is recognised, the other is not undermined.”

Heritage architect Vikas Dilawari brought the group’s attention to the relevance of the radial axis layout, followed in London and Paris, and even in the Fort area in Mumbai, which allows large crowds to move comfortably on perpendicular and parallel pathways. Rani Bagh’s entrance leads to Veer Jijamata’s statue with her son, a young Shivaji Maharaj, and further to the roundabout with Greco-Roman sculptures. The Frere temple here was discovered recently during the restoration of heritage structures.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Rani Bagh has been a space for botany students to study myriad species of trees, from the century-old Sundari and the Looking Glass Mangrove to Krishna Fig, Krishna’s Buttercup, and the Mumbai Sugran which is not found even in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. It also houses the Talipot Palm which flowers only once in its entire lifetime.

In 2016, when the new MHCC approved a tweaked plan,[11] Sukhtankar and former municipal commissioner Sharad G Kale were on the women’s side as they met the then civic chief Ajoy Mehta. He understood, but offered nothing. At the end of that meeting, when they thought they would approach the Bombay high court, Mehta asked if they would work with the BMC if the plans did not affect Rani Bagh. Of course, they would.

Under the eyes of a deputy municipal commissioner since then, the group has been overseeing the work to ensure that the zoo-related changes do not disturb the botanical garden. When the BMC introduced the penguin enclosure in 2017, it was not on the botanical garden land.[12] Till the pandemic-lockdown in 2020, the women saw to it that the trees and their root systems were safe, there was space for roots to spread out, they drew boundaries with chalk for this. They maintain copies of the official plans and drawings.

Only a small plot was exchanged between the botanical garden and zoo which, in fact, allowed a huge and majestic Baobab tree to be in full public view. They had the concrete around the entrance arches removed. By serendipity, they also came upon the Frere Temple that Rustomfram had read about in The Asiatic Society archives; they got it restored too.[13] She clicks photos of weeds around it, as we walk, to send it to the authorities to have them removed.

Back in 2012, to celebrate 150 years of the botanical garden, the Foundation published Rani Bagh -150 years. “This book edited by Nikharge and me has essays graciously written by experts that people can use if the garden is in peril at a later date, when we may not be around to protect it,” says Rustomfram. Contributors include Dr Marselin Almeida, historian Dr Mariam Dossal, environmentalist Bittu Sahgal, Dilawari, trustees and tree lovers like Katie Bagli. The Cajeput tree on the cover, among others, were photographed by Nikharge who walked there at different times on several days in changing seasons. “One Sunday morning, it was in full white bloom. It flowers for two-three days only,” she says.

Photo: Suditi Gupta

Learning and lessons

Steadfast perseverance has no substitute, the women say. They kept at it for more than a decade, sourcing and analysing documents, chronicling the botanical garden, keeping diligent records of conversations, and enlisting the help of willing professionals. Aligning with like-minded individuals and groups, leading the fight, but broadening it to include more people, is also important.

Rustomfram believes that while citizens should criticise the authorities, they also have the know-how to use relevant official provisions. Verifying from multiple sources while comparing data is also important, as is the visualisation, she adds. They superimposed the original plan of the botanical garden with several iterations of the proposed plan; this made it clear to MHCC members how much green space would be sacrificed for the zoo redevelopment. “People listen when you do your homework, apply yourself seriously, and present your facts properly,” she says.

“We still have all the letters chronologically filed,” says Nikharge, “It is important to not leave the subject halfway but take it till the end. Consistency is the victory of any movement.” Over the decade and half, there is enough work done that no one dares to question if it is a botanical garden. Sheila Tanna says they learnt patience besides perseverance. “We had to contend with a lot of double-speak, judge if verbal promises would translate into action, keep our patience through innumerable delays and innovative excuses for those delays. Unfortunately, the official bureaucracy is a tough wall to break.”

Nayana Kathpalia, trustee of civic organisation NAGAR, points to the importance of communicating with authorities. “Advocating for causes that you believe in can be frustrating because you feel you’re getting nowhere but you actually are. Only when you get the authorities to notice, they realise what citizens really want.” Rani Bagh’s botanical wealth, preserved and protected, stands testimony to the fact that a spirited group of women can make a difference. This landmark too, as Sukhtankar remarks, is heritage conservation.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award 2023, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Cover photo: Suditi Gupta