Urban design has been traditionally understood as shaping the physical layout of cities and neighbourhoods, buildings or groups of buildings—the art of making spaces and landscapes or defining the built form.[1] This is a rather limited and outdated approach to a complex and multi-disciplinary field. The way design is understood and practised largely reinforces exclusion, segregation, isolation, and individualization in our cities.

There is an inter-relationship between people, between places and environment, that the structured order of mainstream planning and design are antithetical to. We see the prevailing order and intensifying climate change sever these interdependent relationships. Adding to the complexity of race, caste, religion, class, culture, and gender which play out in physical boundaries and divide city landscapes, the climate crisis is critically affecting lives, relationships and the planet.

Urban planning and design ideas must confront and address these challenges. In fact, urban design understanding must now be based on an understanding of the climate crisis and its impacts.[2] There is an urgent need for urban design to evolve and pursue ‘design beyond boundaries’ in order to influence change in the prevailing order of city-making.

These may be complex and challenging issues but urban designers will also find exciting possibilities. The central objective in urban design must include and reflect a higher state of nature-people relationship.[3] This lies at the core of urban design as intervention. How can urban design focus on these relationships and the complex networks of interactions with new ideas? How can it respond to climate change and work towards social and environmental justice? How can it contribute to the socio-environmental sustainability of cities?

The starting point for planners and urban designers must be to understand and commit to the idea of shared resources, a shared relationship between people and nature, not people over nature. In this context, urban designers must align with people’s organisations and movements that they do not often pay attention to. The focus of urban design, as a discipline, must shift from mere buildings and infrastructure that has colonised our minds and bodies, towards achieving a liberating social order and environmental justice.

Three aspects are important—understanding and honouring nature-people relationship, ecology-centered or climate-sensitive design, and collective intervention or people’s collaboration in nature-based development.

Urban design beyond borders: A nature-people relationship

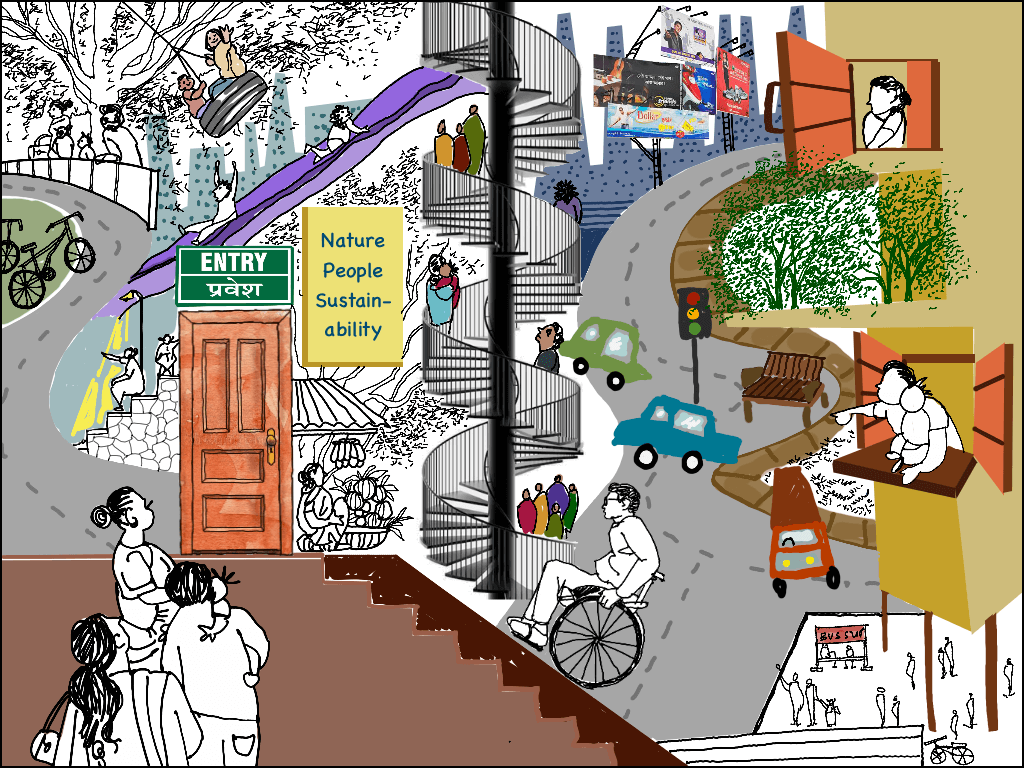

The very act of designing buildings as a tool of intervention in people-people and people-nature relationships is the principle of designing beyond boundaries. Broadly speaking, there are two borders to be consciously breached and gradually erased. First is the plot boundary, the physical aspect. Second is the ideology of territorialism, gated-ness, and exclusivity. The success of a building design must be evaluated by the extent it breaches these two boundaries.

In this approach, a building should be viewed not as a stand-alone, independent, gated, well-packaged marketable product but as an integral part of its immediate precinct or neighbourhood. To unite or integrate a building with its precinct would be to design beyond borders.[4] With this, it is possible to challenge the ongoing fragmentation of the city landscape that we increasingly witness—the segregation of people and places that promotes exclusivity on one hand and exclusion on the other. This could intervene in the neoliberal phenomenon of individualisation promoted by the markets which, in turn, breaks down collectivisation.

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf

When collectivisation is undermined, equality is undermined and debunked too. Equality, by no means, imposes uniformity and unification of the built form in the city but there is certain danger when collectivisation – and unity through diversity – is consciously undermined by the ruling dispensation through land and building policies. Then, forms of discrimination and marginalisation take over that we witness today-–buildings meant for different groups of people based on class, caste, religion, and communities; buildings built with different standards, often in violation of basic human needs, right to shelter, and climatic conditions; buildings that thus become tainted with segregation and divides.

Buildings for the poor are designed and built poorly,[5] stripped bare of the minimum standards of construction, materials, and planning norms. There are fewer or no open spaces, there’s untenable density, token amenities, unbearable maintenance cost, higher heat island effect, lack of privacy for women and space for children. Such low-level building standards trigger severe mental and physical health conditions, and stress community relationships. Buildings for the rich and privileged do not show such oppressive living conditions.

The commitment to integrate a building with its surroundings compels the building to be open and porous. Therefore, the art of designing a building must aim towards a neighbourhood and city without borders,[6] beyond the obsessive individual building-centric approach and privatisation, both of which, amongst others factors, are leading to rapid erosion of urban common property resources and raise questions of accessibility. In physical terms, our buildings are opaque, mono-block, barricaded and controlled—the opposite of what urban design should be.

In his book Speaking with Nature,[7] author Ramchandra Guha writes: “It was in October 1910, the Royal Institute of British Architects organised a major conference on town planning, to which scholars and practitioners from all over Europe were invited (attended by Patrick Geddes). The idea that cities could be carefully and artfully planned was relatively new to the modern imagination, and this conference was an attempt to make architects, accustomed to building discreet structures, more aware of how and what they did fit into the landscape as a whole”.

Ecology-centric urban design

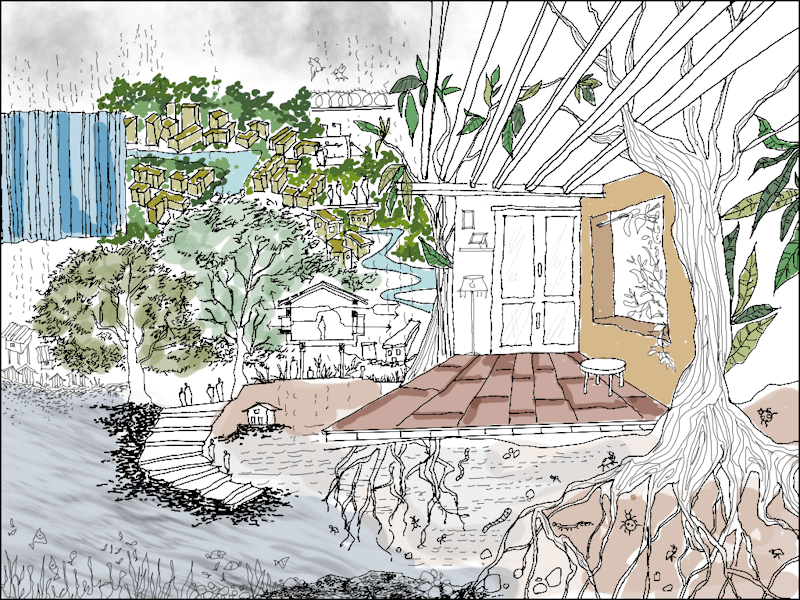

Beyond the individual buildings and placemaking, urban design ideas that deal with multiple buildings and layouts must also commit to, and reflect, an ecology-centric approach.[8]

Illustration: PKDA Architects

In my practice, we in PKDA architects have attempted this. In Konsari township and the Bombay High Court plans (a competition submission), the idea pursued was of multiple buildings or building blocks intertwined with ecological landscapes but not merely decorative, ornamental, and manicured landscapes that’s the celebrated trend. Buildings that intertwine with natural ecology would factor in a response to the climate crisis[9]—rising temperatures, heat island effect, flash floods, rainwater dispersal, low carbon absorption, and loss of biodiversity.

Urban design must contend with these now. In The Burning Earth,[10] Yale University historian Sunil Amrith writes: “The earth charter insisted that human well-being, and ultimately human freedom, depended on ‘preserving a healthy biosphere with all its ecological systems, a rich variety of plants and animals, fertile soils, pure water, and clean air.’ The relationship between human liberty and ecological vitality has become toxic.”

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf

This is most evident about Mumbai, and true of cities across India, in the building byelaws and development control regulations which allow buildings[11] to be constructed without leaving ground-level open space. As a result, we have, in the words of Amrith “turned living nature into lifeless commodities…the outcome of our inability to imagine kinship with other humans, let alone with other species.”

Interestingly, and alternatively, urban design that intertwines with ecology would contribute significantly to better working and living environments, thereby positively affecting the state of mental and physical health and well-being, and productive capacity of the people.

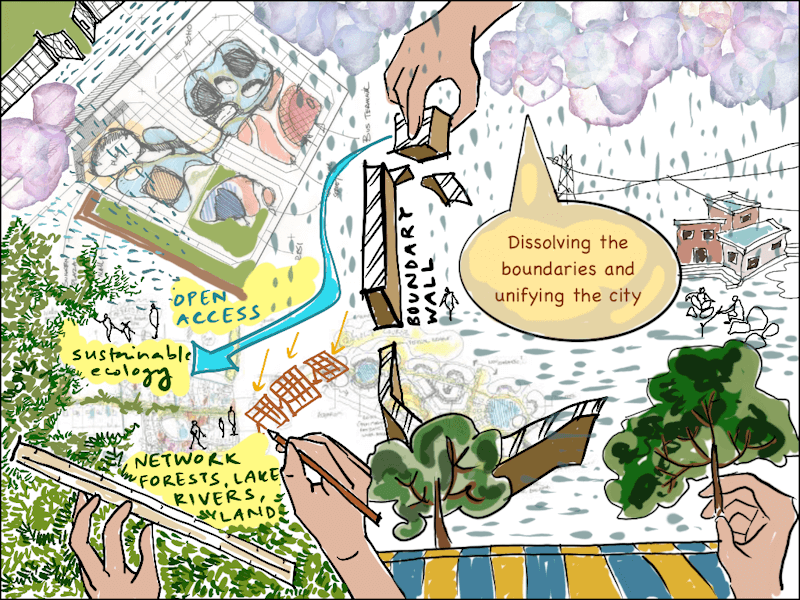

A collective intervention approach

At some stage, it is imperative that urban design moves from individual buildings and clusters to the city at large. An important learning from my life and work in Mumbai is the need for collective intervention which is against the current trend of exclusionary urban design and development. Also, necessarily, every individual intervention must be linked to other struggles for democratic rights which build networks of interventions towards a vision of an equal and just city.

Connecting the dots between natural and built environments, nature and people, and various movements around these issues is an effective way to start creating a new ecology of cities – and, through this, evolve a new intervention strategy and urban design approach. When done this way, by a participatory process over time, that calls for patience besides perseverance and tenacity, we will not only create sustainable and inclusive cities but also build a liberating and sustainable environment for all.

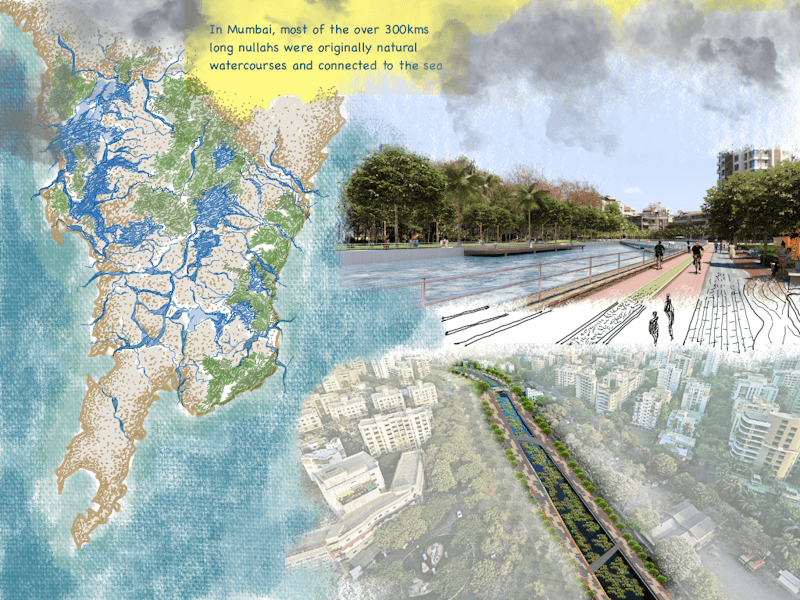

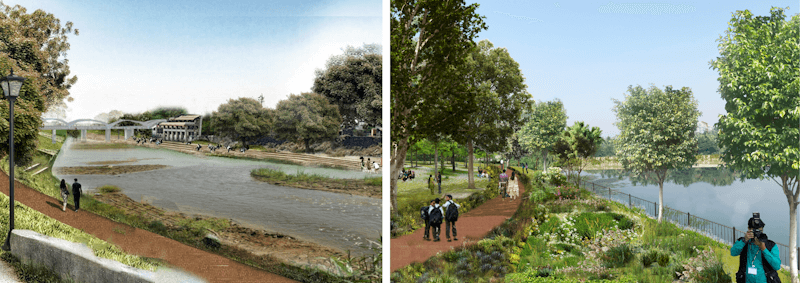

A collective intervention that I was a part of was the Linear Park[12] in Juhu, Mumbai. The filthy and stinking Irla Nullah was converted, by prolonged struggles and negotiations with the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), into a linear park covering four kilometers with naturally-cleaned water (to be completed), rows of trees, cycling tracks and parks that knit neighbourhoods. The collective comprising residents, in association with PKDA Architects, launched the movement in 2012 to bring the people and diverse natural areas of Juhu together. On both sides of the water, people were able to meet, walk, loiter, and cycle. On either side, we also developed ‘city forests’ with thousands of trees.

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf

If adopted and implemented, the BMC could have given nearly 300 kilometres of linear parks to Mumbai. Instead, the authorities built impervious concrete walls along the edges of water courses, damaging their ecology and segregating water from people. Linear parks can define a new landscape, breaking away from large and territorialised spaces like a central park—an idea rooted in the idea of centralism instead of a fluid stream of linear public spaces which meander and modulate across neighbourhoods as water does. Such a stream of open spaces can integrate more areas and people.

Illustration: PKDA Architects

Every city has natural wealth; it is necessary to recognise and include it in urban design. David Maddox, editor of The Nature of Cities[13] writes: “We know that we have a crisis of access to green and open spaces in many cities. We assert that everyone should have access to the benefits of nature and ecosystem services, from the enjoyment of biodiversity to clean air and protection from storms. As a matter of justice, through the lens of equitable access, linear parks are major opportunities in urban design and planning to improve the lives of millions of people.”

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf

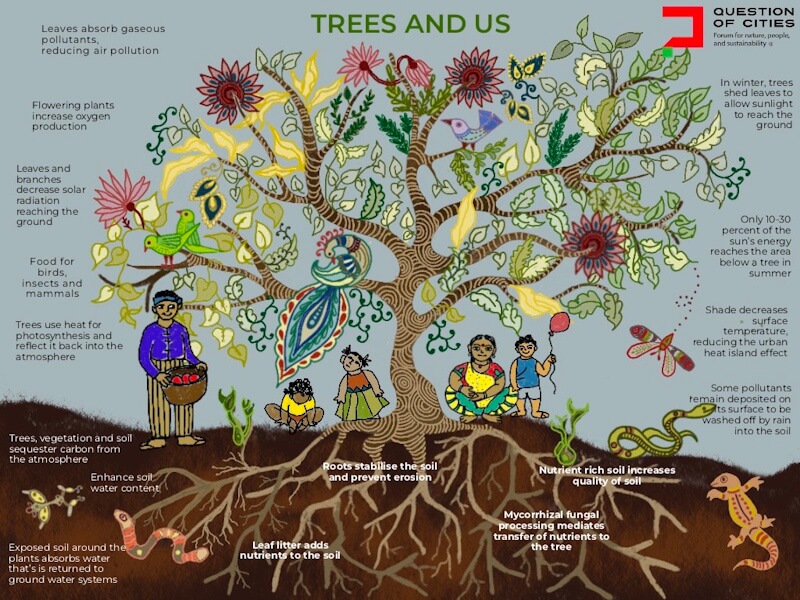

Urban design must pay more attention to a tree or trees as the new sign and symbol, not buildings. Trees provide shade, absorb carbon, release oxygen, maintain moisture levels in soil, check floods, support over half of the planet’s species underground, reduce rising temperature and help mitigate heat island effect and more. Trees also attract people to meet and rest in an otherwise stressful city life. Trees are a life force.

Therefore, urban design proposals must include buildings intertwined with ecological landscapes and imageries foregrounded with trees. For this, it is imperative that cities map their natural ecology including trees and forests, natural streams and waterways, hills and hillocks—not to cut and destroy to build more as in the recent case of Aravalli hills[14] where the Government of India had a skewed definition of hills.

Urban design must contend with two aspects here. One, natural areas have been made invisible and inconsequential which allows governments to exclude them from plans. Two, urban design as well as governments believe it is not important to understand nature and integrate it into plans and designs. When adopted, ecology-centric approach can also foster stronger networking of people in neighbourhoods besides popularising natural areas and realising the benefits of ecosystem services. This naturally helps as an effective climate action programme too.

Conclusion

The shift in urban design from focusing merely on individual buildings or blocks to a wider imagination of neighbourhoods and city rests on the act of seeing. As novelist and art critic John Berger eloquently stated in his seminal work Ways of Seeing: “To look is an act of choice”.[15] Urban designers must consciously and deliberately see the natural areas and the landform in the city, the relationship between different natural elements in ecology, and the relationship between nature and people before designing.

This would take the discipline a step or two closer to weaving the fragmented fabric of the city through nature-led re-envisioning. The Open Mumbai Plan[16] and Juhu linear park project were attempts at this—to map and see Mumbai’s natural areas, recognise them as the foundation of design, and consciously integrate them into the city and people’s lives. When done through people’s participation, it could evolve into a ‘People’s Plan’ strengthening rights-based movements for equal and sustainable cities. Ultimately, participative planning and design must be a right.

Urban planning and design hold incredible power to influence change, address climate crises, break the prevailing order of exclusion to achieve equity-based land use and development, and renew the nature-people relationship. In the re-envisioning of our cities, urban design must dismantle many walls in which it now exists including the formal master planning process that perpetuates hierarchy and control. It must un-barricade spaces, design sustainable spaces and cities that promote harmony and resilience, and protect natural areas as an integral aspect of urban design.

PK Das, urban planner, architect and activist with more than four decades of experience, is also Founder of Question of Cities. He has been working to establish a close relationship between his discipline, urban ecology and people through a participatory planning process. He has received numerous awards, including the prestigious Jane Jacobs International Medal, for his work in revitalising open spaces in Mumbai, restoring waterfronts, rehabilitating slums, and supporting participatory planning.

Cover Illustration: Nikeita Saraf