India has been rapidly urbanising. For the first time, between the Census surveys of 2001 and 2011, the absolute increase in urban population was greater than that of rural population. India’s urban population of 377 million people or 31 per cent is expected to rise to 535 million or 38 per cent by 2026, according to the National Commission on Population.

According to our calculations based on decadal growth rates, urban India will house 654 million by 2031, an estimated 40 per cent of the country’s population. The number of million plus cities in India went up from merely 16 in Census 1991 to 27 ten years later and to 45 in Census 2011; the number of towns in India increased from 5,161 in 2001 to as many as 7,935 in 2011. Most of this increase came from the growth of census towns. The projections are, by 2031, nearly 600 million Indians will reside in urban areas – an increase of more than 200 million in just 20 years.

Clearly, there is burgeoning growth in the population of cities and in the number of cities themselves. India’s cities are centres of commercial activity and infrastructure development. The urban poor, who are often engaged in these activities, are employed as informal labour. The shortage of housing is already a major cause for concern and is expected to exacerbate. According to the report of the Technical Group on urban housing shortage, set up by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation (MHUPA), there was a nation-wide shortage of 18.78 million housing units in 2012.

It is interesting to note that the housing shortage in nine states exceeded millions, with 3.07 million in Uttar Pradesh being the highest and followed by Maharashtra at 1.94 million. Other states faced shortages too. Therefore, creating a sufficient stock of affordable housing is a huge challenge for both the central and state governments as well as for the local municipal bodies.

According to MHUPA’s 2012 report, the Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) and the Lower Income Groups (LIG) face 95 per cent of the housing shortage. An EWS household was defined as one with income up to Rs 5,000 per month and a LIG household with income between Rs 5,001 and Rs 10,000 per month. Subsequently, these limits were increased and, in 2018, stood at Rs three lakh per annum for EWS and between Rs three lakh and Rs six lakh for LIG. This reclassification resulted in a situation where the two sections now account for more than 95 per cent of the shortfall.

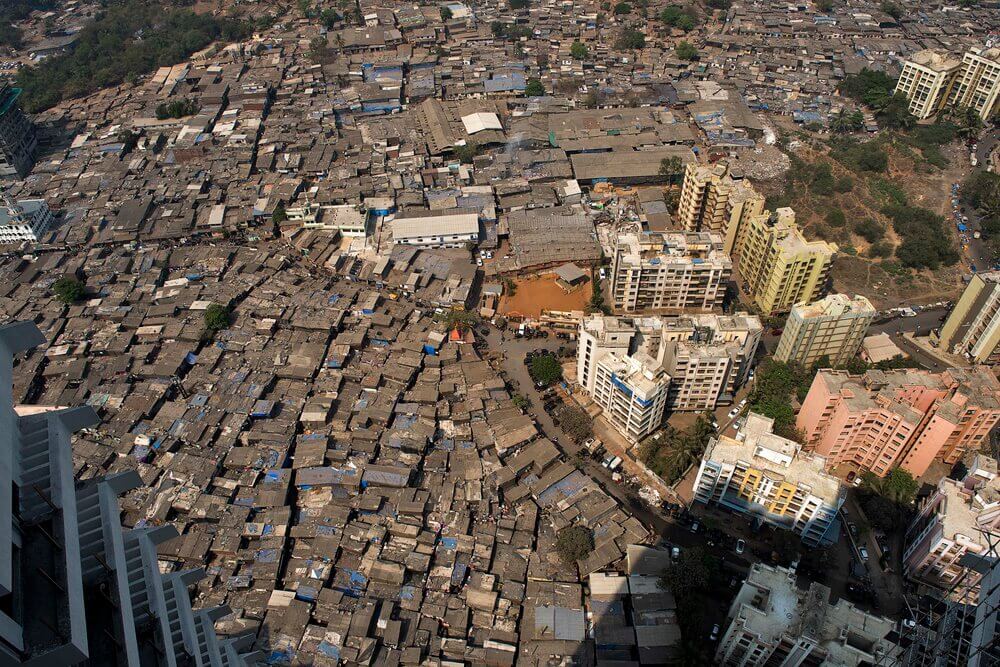

Housing shortage was a constant problem in India’s cities. With urbanisation gathering pace and the population of cities growing rapidly, the requirement of housing units increased consistently. Distress migration from rural areas to urban and peri-urban areas also contributed to the ever- increasing demand for houses. Neither the government nor the market has been able to provide formal, affordable housing to counter the growing demand, resulting in the proliferation of slums.

The irony is that the casual and daily-wage labourers hired by contractors, who contribute to building residential, and commercial urban complexes, remain outside the purview of a legal and permanent home. Usually, people in villages and smaller towns see cities as dream destinations offering a better quality of life. They migrate with the hope of a higher income and an improved standard of living. However, their hopes are often dashed to the ground in cities where a large proportion of the poor find themselves residing in slums, squatter settlements or peri-urban spaces – the seamy underbelly of a glitzy city.

Not shortage but severe shortage

Such urbanisation has resulted in sharper inequalities, specifically when accessing elementary necessities such as housing, toilets, water, health care and education. The MHUPA Technical Group estimates of shortage of housing units (18.78 million) was left far behind by a research report which pegged it at around 34 million by 2022. This implies a three-pronged challenge: a) to clear the backlog of housing shortage, b) to provide for existing shortages in a timely manner and c) to account and provide for shortages that may arise in the near future.

The magnitude of the existing problem and the expectation that it is going to grow in the future should warrant quick action by the government in the direction of rapid reduction in shortages. However, according to information provided by Mr Venkaiah Naidu, then minister of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation in Parliament on March 10, 2016, it is evident that the sense of urgency which the situation demands has been missing.

Naidu, later Vice-President of the country, stated that in three years up to 2016, a total of 4,07,485 houses were completed jointly under Jawaharlal Nehru Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) and Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY). At this rate, it would take 138 years to build 18.78 million housing units.

Any discussion on housing in this context turns to affordable housing – a wide-ranging phrase which has been used by governments and the private sector alike often to seize control of land in cities. Affordability, in the context of housing, is a much-abused term which has meant different things to different people.

What is affordability?

The term ‘affordability’ is frequently used in relation to income, the connotation changing as income levels vary. The lack of affordable homes means the poor are forced to lead a life devoid of the basic human right to a dignified and safe dwelling. It is in the context of the urban poor that the lack of affordable housing becomes a multi-faceted form of deprivation. Often, the household spends a large proportion of its meagre income on housing and is left with a substantially reduced amount to spend on other needs such as food, health care and education. Housing affordability thus contributes to other forms of deprivation as well.

Finding affordable homes is a serious challenge in a large number of our cities. Not having any other option, households are often resigned to living on hazardous lands such as dumping grounds, along nullahs, and hill-slopes that are vulnerable to landslides and flooding. Health issues that arise due to the lack of sanitation and water facilities only add to the misery of a large proportion of urban dwellers. Additionally, the sizes of units that people are forced to live in and the lack of optimum open spaces cause congestion trauma.

Gan and Hill, in their 2009 paper, elaborate on the concept of affordability.[2] They exclude owner-occupiers, arguing that affordability is not an issue of “direct relevance to owner-occupiers who have already purchased a home.” Instead, it is the first-time would-be home buyers who are directly impacted.

Affordability can be conceptually identified in three ways:

i. Purchase affordability which measures the ability of a household to gather enough funds in order to purchase a house.

ii. Repayment affordability which measures the ability of a household to be able to make the mortgage payments.

iii. Income affordability which measures the ratio of house price to income.

Usually, affordability is measured by the ratio of median house price to median income. The International Standard given by UN-Habitat requires this ratio to be between 3 and 5, depending on income levels. The MHUPA defines it as: “Generally, affordability is taken as three-four times the annual income. However, in all schemes and projects where subsidy is offered by state or central governments for individual dwelling units with a carpet area of not more than 60 square metres, then the price range of a maximum of five times the annual income of the household, either as a single unit or part of a building complex with multiple dwelling units will be taken as affordability entitlement.” This is a broadly fair definition of what an affordable home is.

What affordability means in Mumbai

In Mumbai’s context, for those at the bottom of the income pyramid, the cost of an affordable home for ownership should span between Rs six lakh and Rs 20 lakh, to bring it within the reach of a family whose income is between Rs 10,000 and Rs 30,000 a month. Additionally, there is also the distance which relates to housing costs; as housing layouts go farther away from the city centre, the dwellings become more affordable, as research has shown.

However, the economic and temporal cost of transportation increases, and the housing cost is replaced by transportation cost, as Kalpana Gopalan and others showed.[1] Given the linear topography of Mumbai, the travel time from the periphery to the workplace can be as much as 2.5 hours. It is also important to consider the liveability of the dwelling and surrounding areas. The physical infrastructure and amenities provided make a significant difference to the liveability. Location issues are important in an urban settlement; social factors, community networks and familiarity are critical too.

Costs related with maintenance, power, water and property tax also need to be taken into account, as Gopalan showed. Often, it has been observed that slum-dwellers settled in formal housing find it difficult to pay these costs given their meagre incomes. As a result, they move out to another slum where the purchase price and/or rent is more affordable for them while informally letting out their property or selling it. In many slum redevelopment projects, some beneficiary slum-dwellers sold or rented their tenements to move to cheaper places, including other slums, in order to meet healthcare, educational and other social needs.

Hence, it is important to take into account the many factors and costs for successfully achieving the target of accommodating all citizens in formal housing. “Adequate shelter means more than a roof over one’s head. It also means adequate privacy; adequate space; physical accessibility; adequate security; adequate lighting and ventilation; adequate basic infrastructure – all of which should be available at affordable cost,” according to the high-level task force on Affordable Housing for All, December 2008.

The UN-Habitat III, in its Quito conference in October 2016, published various issue papers. The one on housing stated that “Adequate housing was recognised as a part of the right to an adequate standard of living in international instruments including the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.” The Government of India is a signatory to this covenant.

The Habitat III Paper also made it clear that “adequate housing must provide more than four walls and a roof…affordable housing is not adequate if its cost threatens or compromises the occupants’ enjoyment of other human rights.” The provision of affordable and adequate housing must be therefore judged from an assessment of its success or failure in terms of human rights. In short, housing is not a commodity that can be manufactured in repeated and monotonous building blocks, packed without open spaces and social amenities with the sole obsession of maximising financial turnover which is currently the single-most dominating factor in dysfunctional markets.

Affordable housing includes rentals

The Habitat III Paper pointed out that “inadequate housing has contributed to health inequality and risk exposure. The home is a major environment of exposure to hazards and health threatening factors due to lack of habitability, overcrowding, and inadequate services, among others. Crowding is among the most serious threats as it enhances the transmission of diseases.” Both private and government housing finance agencies have considered housing finance through mortgages. In this regard, the Habitat III Paper pointed out that mortgage “has often been feasible for the middle- and high- income groups rather than the most needy 60 to 80 percent… Subsidies (are flowing) to those who need least.”

The concept of affordable housing also covers rental housing and the availability of houses to rent. The opportunity to access rental housing is necessary for large sections of population in any city. This includes the very poor but it also covers those who have other priorities or compulsions of expenditure, either healthcare, education or other liabilities in the family and would therefore like to access housing on rent on a temporary basis.

Besides, there are a large number of people in cities who are likely to move within the city or are on temporary or transferable jobs. For such people, owning a house is not a necessity. Even otherwise, ensuring a regular payment of EMIs on loans taken to purchase a house is a burden for most families. All such people prefer good rental housing, while choosing to spend for other needs which can enhance the quality of their lives.

It is the availability and access to housing, ownership or rental, that are fundamental to human development and also become the mark of a developed city. It is the lack of access to dignified housing, as in Mumbai, which undermines the very idea of cities and urbanisation.

These are lightly edited excerpts from the publication Chasing the Affordable Dream: A Plan to House Mumbai’s Millions by the authors. PK Das is a well-regarded architect-activist involved in the housing issue for more than three decades who along with Gurbir Singh, senior journalist and Consulting Editor for The New Indian Express, and others co-founded the Nivara Hakk Sangharsh Samiti; Ritu Dewan is the founder-member of the first Centre of Gender Economics; Kabir Agarwal is is an independent journalist who writes on public policy, the economy, climate change, energy and national security.

Photos: PK Das & Associates