In New Delhi’s bustling Kamla Nagar market, on Bungalow Road, is a makeshift stall like thousands across the city. Here, Anita, a mobile vendor who sells kurtis, is always watchful of having to negotiate with forces other than her customers such as sudden heat or flooding and harsh officials. Of late, she has had to factor in the central government’s ‘beautification drive’ too which makes no space for people like her in the city. This market is a lifeline for countless vendors offering a wide range of goods to diverse customers from college students to bargain-hunters. There’s not only police and municipal harassment and confiscation of our goods routinely but we are forced to pack up despite having valid licenses, sometimes when it’s too hot or cold, said Anita.

About 15 kilometres away in Seemapuri, the story echoes. Sheikh Akbar Ali, a waste worker, could not tolerate the heat. “Earlier, we would first sort the waste to separate the recyclables to be sold. Since the government installed the compactors, the machines crush all waste together, forcing us to sift for recyclables making it more challenging, especially in extreme heat or rain,” he said. The compactors were part of the ‘beautification drive’ before the G20 Summit. Ali has since started commuting to landfills far away in search of recyclables, in high heat. “All this has increased my expenses,” he lamented.

Informal workers like Anita and Ali, many working outdoors, form an astonishing 80 percent of Delhi’s total workforce, according to this report Women in Informal Employment: Globalising and Organising,[1] which is almost twice the national average of 49 percent outdoor workers in India’s total workforce Periodic Labour Force Survey 2022-23[2]. Nearly half of Delhi’s informal workers also live in precarious informal settlements which offer little security from extreme weather events, they are not assured minimum wages or income protection, and have virtually no safety nets.

Urban master plans and climate action plans which do not account for them directly undermine their Right to the City, which mandates that urban spaces are accessible, equitable, and inclusive for all people and they have a say in the city’s decision-making. When this right is upheld, the city becomes a space where people from all walks of life can partake in its opportunities, culture, and social fabric. The absence of the Right to the City is not merely abstract; as in Delhi, it has tangible, often dire, consequences for those who are denied it.

Unpredictable weather, vulnerable millions

It is not only the heat. Delhi is projected to suffer losses of Rs 2.75 trillion by 2050 due to various impacts of Climate Change. This comes from the Delhi government’s draft action plan on Climate Change. Yet, the next move – to secure the lives and livelihoods of the vulnerable – has not happened.

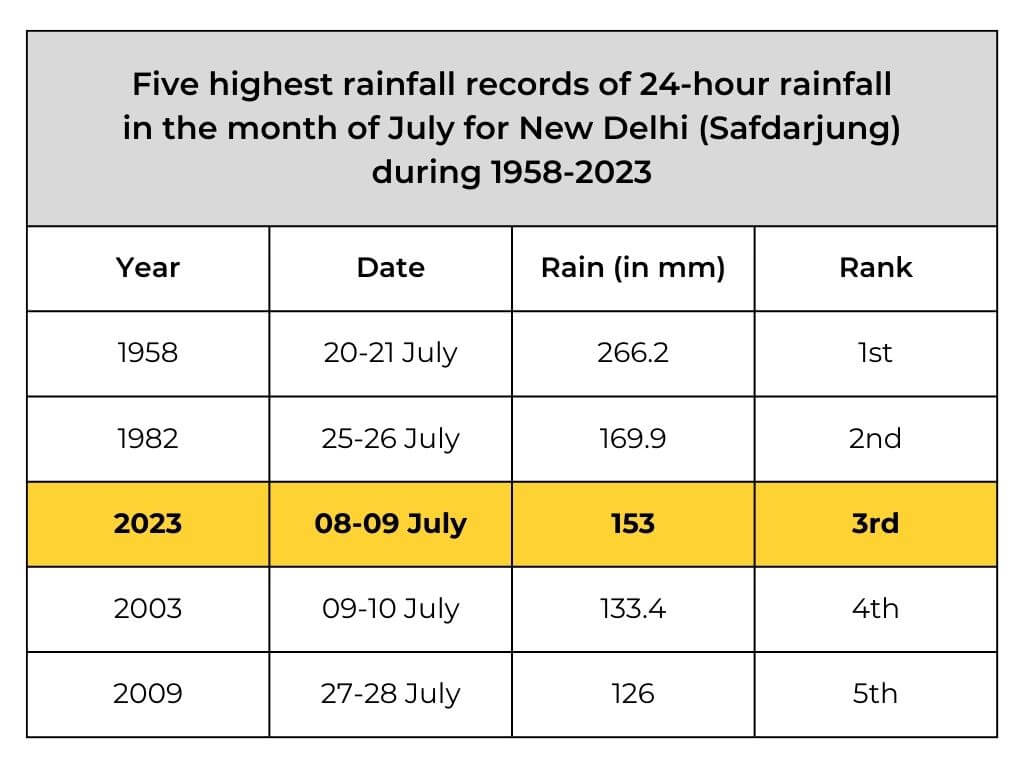

This monsoon, Delhi broke a 41-year rainfall record[3] due to a host of climatic factors. In only 36 hours, on July 8-9, the city recorded an unprecedented 260 mm rainfall, prompting the government to issue a flood warning and shut schools temporarily. The water level in the river Yamuna reached a record high of 208.66 metres, well above the previous high in 1978.

With extreme heat waves and rainfall, the city is shivering through more intense cold waves too. According to the IMD, the national capital experienced eight cold days in January 2023 – the second-highest in 30 years and the most in a month in the past 15 years. This January, Delhi also witnessed its longest cold wave in a decade, lasting five days from January 5 to 9. In 2021, Delhi recorded a minimum temperature of 1.1°C on January 1, which is the lowest reading for Delhi’s base station in 14 years.

In the past few years, records show that Delhi has been experiencing comparatively warmer Decembers and sharp declines in temperatures in January. This, experts say, is because of the climate crisis which is changing temperature patterns resulting in shorter but more intense winters. The city is, in fact, in the throes of what’s called the Compound Climate Extremes where one extreme climate event results in multiple crises.

To not account for this in planning in a city where millions work outdoors and live in informal settlements begs the question: Who is the city for?

Work and high heat

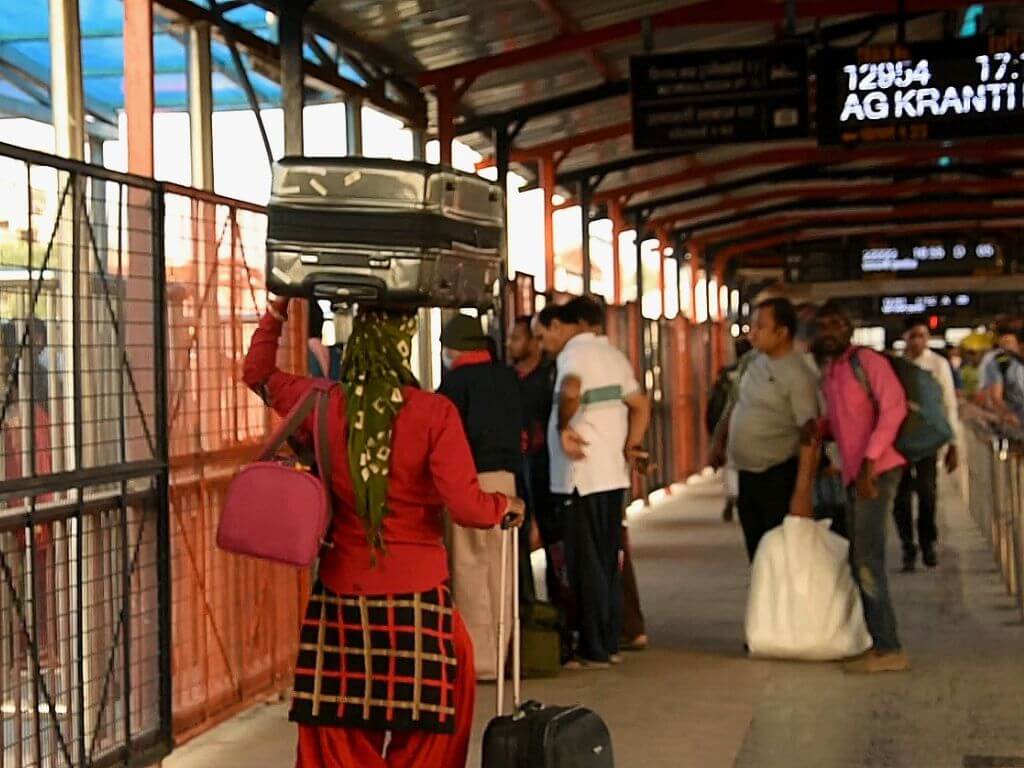

Lalita Devi, a porter at Delhi Cantonment railway station, got her first customer at 3pm on a terribly hot summer day. “As soon as I lifted the luggage, I felt intense pressure on my head and immediately fell unconscious. This has never happened before. How will I work?” she asked. Like her, Shakeel at Nizamuddin railway station too fell unconscious several times this harsh summer. Many among the 532 porters at Nizamuddin have similar tales.

What makes it worse is that they do not have cool homes to return to. “There isn’t even cold water to comfort my husband after he returns,” said Rubina, who lives in one of the rehabilitated jhuggi jhopdi (JJ) clusters. These clusters are veritable heat islands in themselves, hotter than their surroundings because of the materials used and the absence of cooling mechanisms. The Madanpur-Khadar cluster, for example, has nearly 450 houses of displaced people, its dingy rooms located over a sewage drain with neither ventilation indoors nor open spaces outdoors.

In such clusters, food security is also an issue. Ankit Negi, a mobile phone vendor near Saket metro station, makes about Rs 500 a day, a quarter of which he spends on his food. “I skip lunch some days in summer so I can buy sugarcane juice…if not, I feel like I might collapse,” he said. Food plate prices surged by 28 percent on a year-to-year basis, according to this report[4] by Crisil, while wages[4]. fell by 0.2 percent this year. The high heat, with no relief measures offered by governments, leave people to fend for themselves within their meagre means, showing yet another way climate events intersect with people’s Right to the City.

Lawyer and urbanist Mathew Idiculla, in this paper ‘A Right to the Indian City? Legal and Political Claims over Housing and Urban Space in India’ [5] argued for invoking the Right to the City as a core part of human rights in the context of housing. Inadequate shelter and food makes climate-related events worse for the most vulnerable, as this report ‘Increased labor losses and decreased adaptation potential in a warmer world’[6] highlights. Sweltering or humid conditions contribute to productivity losses. Globally, the International Labour Organisation[7] projects a 5.8 percent surge in working hours lost by 2030 due to heat stress. In India, this could hurt millions across the informal sectors.

Criticality of adequate public transport

“We don’t have cars; we use buses to commute daily but we don’t get adequate services. In May and June, it feels like being in a pressure cooker,” said Anita Kapoor from Shehari Mahila Kamgar Union. “Worse, bus conductors mock us by calling us pink ticket wale. Buses don’t halt at the bus stop if there are only a few women waiting,” she articulated at a consultation on the City Vision Document and Delhi Slum Policy. Many women elaborated on how high heat and rain worsen this. Their testimonies are confirmed by surveys such as by Greenpeace India.

Local buses are the only transport option for millions living in distant resettlement colonies around Delhi where the metro is an unaffordable option[8] even if it services the colonies. Travelling in non-air conditioned buses for hours in a heatwave can feel like being in a giant oven[9]. The Public Transport Forum, Delhi, and Greenpeace India asked the Delhi Transport Corporation for a Mobility Heatwave Action Plan. Though the government published a Heat Action Plan (HAP), it does not effectively address mobility in the context of heat. It suggested that buses should not run between 12 noon and 4pm during peak heat but did not offer air-conditioned services.

Shutting down bus services disregards informal workforce who have no office hours nor recourse to private cars; Delhi does not have a well-connected affordable system like the suburban trains in Mumbai. The colonial Delhi was described as “planned by, and essentially for, the automobile-owning class” with the city’s post-independence planning continuing this pattern, according to N. Evenson’s The Indian Metropolis: A view toward the West.

The HAP does refer to the need for cooling shelters, cool roofs at bus stops and bus depots, but does not mention the sources of funds or implementation process which may well mean that this remains on paper. An analysis of HAPs by the Centre for Policy Research showed that only three of the 37 plans had identified funding sources and eight asked implementing departments to generate resources. Delhi’s plan was formulated after the analysis but suffers from the same lacunae.

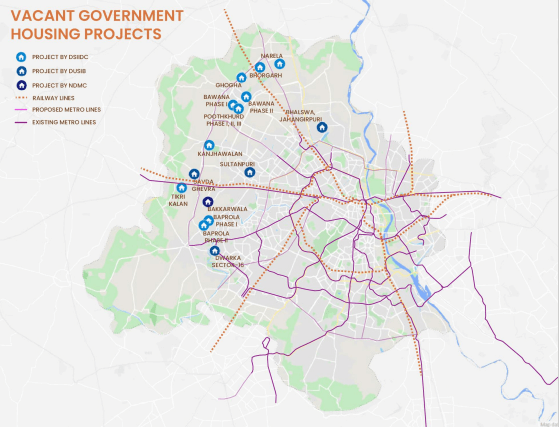

Improved housing is a conundrum. In September 2020, Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board suggested rehabilitation of people in the JJ clusters in around 46,000 government flats built under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission[10] but these are on the outskirts of the city which make reliable and safe public transport even more important.

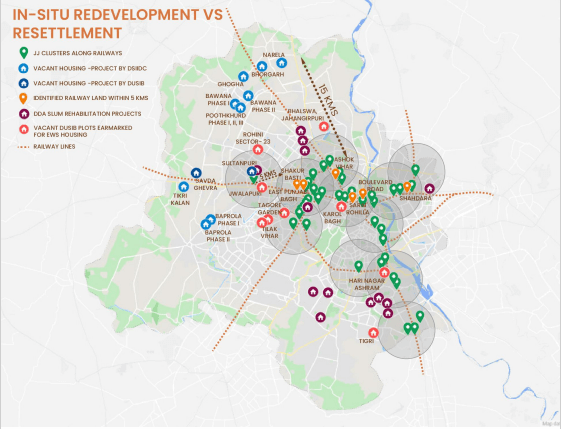

Map: Social Design Collab, Missing Basti

This is in violation of the government’s own policy[12] of rehabilitation of slums and JJ clusters which provides for rehousing either on the same land or within a five-kilometre radius. The location matters to the poor because their worksites are usually in the vicinity of their homes. Naturally then, as media reports[13] showed, the resettlement colonies have become ghost towns.

In city, out of city plans

The non-provision of adequate buses or ill-advised location of resettlement colonies are not accidents or casual occurrences in the life of Delhi; these are the intended outcomes of urban planning in which the rights of the poor and marginalised are barely recognised or, at best, paid lip service to.

Planning has meant the government at the steering wheel. It relied on technical experts and excluded local knowledge and communities. This top-down bureaucratic approach and a plan’s disconnect from reality was exemplified in the 1961 Master Plan, the formulation of which was outsourced to a team led by American architect-planner Albert Mayer. Citizen consultations, when held, were restricted to registered residents’ welfare associations from middle and upper-income planned neighbourhoods or elite industry associations. As a result, Delhi’s master plans have been disconnected from the majority of its residents while envisioning the city as an orderly and neatly-zoned domain with formal housing and office-goers – a far cry from the lived city.

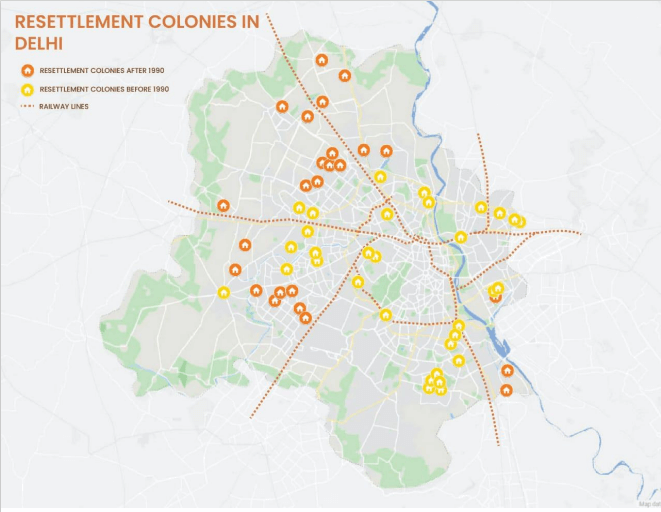

If putting the informal and vulnerable on the periphery is a neoliberal idea, then Delhi’s plans have amply displayed this. The Map Essay[14] below, by Missing Basti, compares the resettlement of slums and JJ clusters before and after 1990 which illustrates the systemic push to move the urban poor out of the city. The post-liberalisation spatial segregation of the poor to the urban periphery is hardly a myth; it is self-evident, as pointed out by A. Kundu and Ray Saraswati[15].

In the essay The Dream of Delhi as a Global City[16], author Veronique Dupont characterises this development vision of beautification: “…the capital’s redevelopment and beautification has often resulted in pushing unwanted slums further out of the city’s physical and economic spaces, without solving the issues of adequate shelter for their dwellers. Moreover, since slum demolitions entail the destruction of poor people’s investments in housing and improving the microenvironment, such operations systematically impoverish the affected families”.

A study[17] done by Social Design Collab argues that there is sufficient land in the city itself. Its founder and architect, Swaati Jaanu, said, “People build jhuggis because the housing policies do not cater to their needs, the state has put the responsibility of affordable housing on private players. This model has not worked in Mumbai with the SRA…Build more houses for the poor in the city and change the definition of illegality when it comes to deciding who has the right to live in the city.”

Delhi’s narrative on Right to the City and climate issues is a striking illustration of the mindless application of old western planning ideals. The challenges associated with exclusion and the growing socio-spatial polarisation do not find enough articulation in the context of Climate Change-driven policymaking. Any which way sliced, the Right to the City is the cornerstone of a just and equitable city. When unrecognised, denied, and exacerbated by climate extremes, millions are condemned to a life of insecurity, hazards and hardship.

Way forward

It is now well accepted, as in the UNDP report, that access to assets improves the resilience of informal workers in the face of Climate Change[18]. If the state-provided social protection is combined with individual responses, they do get a robust safety net to tackle climate events. The landscape of social security in Delhi, as in India, is a complex web of fragmentation which poses substantial challenges for workers and policymakers. At the core lies the absence of a unified database for unorganised workers and the wide dispersal of social security schemes across union, state and local governments. This compartmentalisation does not help people who are forced to navigate labyrinthine processes to avail benefits.

The ramifications multiply when it comes to the portability of social security schemes, especially for migrant workers. Although the Occupation Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code of 2020 attempts to improve the accessibility of social security schemes, particularly concerning the Public Distribution System, it grapples with formidable administrative and financial challenges. For example, questions arise about whether the “source” or “destination” state is to bear the financial responsibility for providing social security benefits to migrants.

To campaign a worker-centric urban development approach, a team of Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) joined forces with allies to work towards a better and equitable Master Plan 2041 for Delhi. They advocated a livelihood-centric perspective in urban planning with suggestions to build multipurpose community centres, and decentralisation of access to essential social services. The coalition chose to directly engage in the city planning process, away from mere criticism or advocacy, to see how best the Master Plan can integrate informal workers into the city’s landscape for not merely a habitable city but also a compassionate one.

Yet, these efforts could integrate Climate Change issues too to make the planning more responsive to the urgent issue of our times.

Hrushikesh Patil is a Maharashtra-based independent journalist and environmental lawyer interested in covering the impact of Climate Change-induced disasters on vulnerable communities. Currently working with the Goa Foundation as lawyer and researcher, he is also a member of the environmental communications and advocacy volunteer collective called ‘Let India Breathe’ and is a recipient of many awards.

Sejal Patel, an independent journalist and documentary filmmaker currently working from Delhi, keeps a strong research focus on rural communities and data journalism, as well as the application of artificial intelligence (AI) to the fields. Patel holds a postgraduate degree in Convergent Journalism from AJ Kidwai Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia. Through her work, she aims to challenge established norms, foster social justice, and instigate transformative change.

This is the second essay in a series supported by the QoC-CANSA Fellowship on Climate Change and cities in four nations of South Asia. The first can be read here.

Cover photo: Pinki, a woman porter at Nizamuddin Railway Station, lifts luggage up to 70 kgs every day.

Photos: Sejal Patel