The screams and howls of birds and animals are unforgettable for those who have seen the video of the assault on 400 acres in Hyderabad’s Kancha Gachibowli by 50 JCB excavators and bulldozers this week.[1] This large swathe of land was being cleared by the Telangana government to pave the way for an IT park.

Hundreds of students from the neighbouring Hyderabad Central University came out in protest,[2] shot and shared the videos, and made sure that the world knew what the government was up to. The Supreme Court halted all activity.[3] Yet another green area, complete with its ecosystem and biodiversity, was being sacrificed at the altar of ‘development’ or construction. We heard only peahens but who knows what complex and rich biodiversity was mercilessly wiped out?

This was reminiscent of the assault on more than 2,200 trees in Mumbai’s Aarey forest in 2019 to make way for the car shed of the underground metro. People vehemently protested but it was in vain. It is not only the major metros of India where the ‘build more’ approach has meant a direct assault on the natural areas such as forests, hills, open spaces, rivers, lakes and other watercourses. Smaller cities and towns too are showing the trend. In Alibaug, once a sleepy coastal town that people in Mumbai escaped to, new construction and redevelopment are in full swing altering its skyline and very character for the local people. The story repeats itself in Dehradun, Guwahati, Shimla and other cities.

In a report submitted to the National Green Tribunal this March, the central government disclosed that 13,056 square kilometres of forest area is under encroachment in 25 states and Union Territories.[4] This encroached area is more than the total geographical area of Delhi, Sikkim, and Goa combined. While a rural-urban split of the total area is not available, it is likely that a large part of it has been in cities that rapidly expanded their footprint.

It is not our case that there should be no urban development or building activity where natural areas stand but the current model of development pushes its agenda of more-and-more construction with little thought to its ecological consequences. It is important to pause and ask whether construction is happening in a sensible and ecologically-sound manner or it is just an extractive building spree. Rapidly losing natural areas – natural wealth – to development cannot give us sustainable cities.

Just how much more is the built-up area in a city compared to say five or ten years ago is not a statistic that’s easily accessible or available. If such data is available and accessible, then it’s not comparable to the past or across cities. This is not a bug in the development paradigm; it is a deliberate feature that allows the powerful to obfuscate the reality, minimise people’s anger, and keep their power. It’s by design. If people know, people’s resistance will be stronger.

Rapid expansion

The construction sector has been one of the key economic sectors contributing to the country’s GDP and it has grown by leaps and bounds. Its compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) is projected to be 9.14 percent from 2024 to 2032 and building-construction market is projected to grow from USD 271.13 million in 2023 to an estimated USD 596.63 million by 2032 (Rs 5,089.85 crore)[5]

The corresponding land expansion across India is reflected in the National Remote Sensing Centre’s assessment titled Annual land use and land cover atlas of India.[6] It states that the built-up area has expanded by almost 2.5 million hectares over the past 17 years from 2005-06 to 2022-23, underlining rapid urbanisation and infrastructure growth during this period.

Master plans or development plans of cities have been about land use and land expansion, but have failed to balance these with natural resources. In fact, most plans have even sidelined transportation, energy, water, resources, waste management all of which are important for sustainable and liveable cities.[7] A large part of urban India does not even have plans. A NITI Aayog report of 2021,[8] found that 65 percent of India’s 7,933 urban settlements lack master plans.

The plans have not, cannot, prevent the encroachment of built-up areas into natural areas; not having plans probably makes it worse as concretising green areas, levelling hills, destroying forest cover, disrupting natural water networks, choking streams and lakes, and more goes on. The outcome of this seen in the water crisis in Bengaluru last year, urban heat island effect seen across cities in summer, lingering air pollution set to intensify.

Here’s a look at the extent of the built-up area expansion in some cities, in alphabetical order, over the past few years.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ahmedabad: Neoliberal transformation

Between 2001 and 2021, Ahmedabad’s built-up area increased by 37 percent, found this study, Predictive modeling of land cover changes in round-1 smart cities of India using cellular automata and GIS while other studies have shown that open land, forest land, and agricultural land have been shrinking to allow more built environment.[9]

If the period 1990 to 2019 is considered, the total built-up area grew by 130 percent and the fastest decadal urban growth of 52 percent happened from 2000 to 2010. “The semi-arid landscape of Ahmedabad had little greenery by way of trees or parks—mostly agricultural fields and scrub. The westward greening was driven in part by institutional campuses, though not solely. While they once supplemented public parks with conditional access, narratives of safety and security eventually sealed them off from the very neighborhoods they inhabited,” says Shubhra Raje, an architect and educator. The controversial Sabarmati Riverfront project, central to Ahmedabad’s neoliberal transformation, has choked the river’s natural flow and further polluted the river.[10]

Alibaug: Sleepy town wakes up to real estate boom

The coastal town, around 100 kilometres from Mumbai with barely 2.6 lakh residents, was a quiet and popular weekend getaway. With a plethora of infrastructure development in the past few years, the sleepy town has been seeing a multi-fold increase in tourists and elite homebuyers[11] with its population rising to nearly six lakh. The RoRo facility, Atal Setu that connects Sewri to Nhava Seva, a new Karanja-Revas (Alibaug) bridge over Dharamtar Creek bridge have made it more accessible, driving the surge in real estate demand. The national highway NH4 from Mandwa Jetty to Alibaug now resembles a local congested road, several large luxury gated complexes are being planned and advertised, and the town has seen nearly 13.8 percent rise in its real estate prices in barely a year.[12]

As the concrete jungle of villas, hotels, and high-rises expands, concerned architect Pinakin Patel, who moved here 25 years ago, has urged the Maharashtra government to draft a zonal plan to preserve Alibaug’s green spaces. Government rules now allow high-rise residential towers, mini townships and five-star hotels, and big developers have announced their plans to construct these. Patel reiterates, in this interview to The Hindustan Times,[13] that he is not against development, only that Alibaug should not turn into an “unplanned urban hellhole”.

Bengaluru: Garden city transforms to IT parks

Situated on a high altitude, Bengaluru is mostly ridges and valleys. Manyata Tech Park, which saw severe flooding in 2024, was built on a valley area and over the Nagavara lake wetlands. The area first saw floods in 2021 even though the rainfall was not too heavy. “That was the time when everyone woke up and said that flooding also happens in high-income neighbourhoods,” Sairama Raju Marella, architect and urban planner who works at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements (IIHS) told Question of Cities.

A recent study[14] shows Bengaluru’s urban cover will increase to 1,323 square kilometres this year – almost twice that recorded in 2017. Between 1991 and 2017, Bengaluru’s urban area expanded by a whopping 348 percent, the boom seen after the economic liberalisation in 1991 which turned the city into an IT hub. In the last five years, Bengaluru has absorbed more commercial real estate than London, New York, Singapore, Beijing and Hong Kong put together.[15]

Trees have disappeared at an alarming rate. In 1970, 68 percent of Bengaluru had trees which is down by 4 percent now.[16] The 920 tanks and lakes in the 1960s had dwindled to just a little over 100 lakes, as per reports from 2012.[17] Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike’s (BBMP) website states that there are “167 lakes in BBMP custody”.[18]

One of these is the Rachenahalli lake, spread across 104 acres, which used to support agriculture till about 2000 but the area – including Manyata Park – has begun flooding.

Bhubaneswar: From planned to unplanned

One of the first planned cities of independent India, Bhubaneswar, has expanded in an unplanned and haphazard manner in the past decade. Over the years, there has been 44.77 percent increase in built-up areas and 15.11 percent of crop lands have been changed to other land use, found the research paper Land use/ Land cover change analysis of Bhubaneswar from 1973 to 2017.[19]

Photo: Shobha Surin

The Chandaka wildlife sanctuary, which used to be on the city’s outskirts, is now surrounded by urban development. The edges of 20 square kilometres of Bharatpur Sanctuary, a part of the Chandaka, are now dotted with apartments, office complexes, hospital, roads and illegal settlements. Bhubaneswar’s area increased from 25 square kilometres in 1951 to 135 square kilometres in 2011.[20]

Chennai: Battling floods and water crisis

With a 25 kilometre coastline, leafy avenues, and major rivers — Kosasthalaiyar, Adyar, Cooum — flowing through it, Chennai is rich in ecological heritage but rampant urbanisation has made the city less resilient to natural disasters. The severe flooding in 2015 followed by water scarcity in 2019 are directly linked to the shrinking wetland areas, found the Living Planet Report 2024. Rapid urban expansion resulted in an 85 percent decline in the area of wetlands.[21]

The city’s urban cover increased from 50 square kilometres in the 1980s to 5,904 square kilometres in 2020 and Chennai was divided into Chennai City and Chennai Metropolitan Area over a period of 40 years. The reason was the increasing population, which was growing at an average of 2.3 percent every year.[22]

Delhi: Expansion ruins charm

The country’s capital has always been a charming city. Majestic buildings, old colonial structures, iconic landmarks, the Yamuna, lots of trees and open spaces, parks made Delhi a beautiful, walkable city. But the city has expanded to encompass more residential, industrial, commercial, institutional areas, and dense transport networks had to be built. In 1989, the built-up area of Delhi was 246.07 square kilometres which increased to 291.49 square kilometres in 1999 and 585.91 square kilometres in 2019.

In 2006, the Delhi government declared relocation of industries and 27,905 units were eligible for allotment of industrial plots and flats in Patparganj, Narela, Badli, Bawana, and Jhilmil and flatted factories (Industrial Policy for Delhi).[23]

Now, Delhi is known for rising temperatures, flooding and worsening air pollution[24] and one of the reasons is urbanisation. The heavily polluted Yamuna has become a dump yard that severely flooded the city in 2023.[25]

Guwahati: More concrete, less greenery

Assam’s largest city, Guwahati, recorded a 61.2 percent growth of built-up area between 2002 and 2015 even though its population grew at only 17.7 percent, finds a research paper Simulating urban land use change trajectories in Guwahati city, India. The development damaged the ecology,[26] ate into recreational open spaces and vacant lands and damaged the hills and other natural land covers. From 1976 to 2018, the forest cover of the Guwahati Metropolitan Area (GMA) declined with dense and moderately dense forests in the urban areas decreasing by 44 percent and 43 percent respectively.[27]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Urban planner and architect Urmi Buragohain says the transformation started in the 1970s when the capital was shifted to Dispur from Shillong. “Guwahati expanded so much that Dispur has become a neighbourhood within Guwahati city. It attracted a lot of people from all over northeast and outside too,” says Buragohain. The past decade or so has seen exponential growth[28] with infrastructure spread such as roads, flyovers, foot-over bridges, and bridges over rivers.

Buragohain remembers growing up in the 1980s in a house surrounded by paddy fields and watching birds from the backyard; the paddy fields are long gone and houses are replaced with apartment blocks. Who worries about the birds? “The roads have remained small laneways and open drains have been covered to make more space for the increasing number of cars,” she says. There is a master plan but it focuses on decongesting Guwahati by shifting functions to its northern area, across the Brahmaputra although there is no public transport connectivity there, she adds. The city, once surrounded by hills, water bodies and wetlands, is fast losing them.

Kochi: A balance in building and conserving

Before the Kerala Conservation of Paddy Land and Wetland Act, 2008, came into force on August 12, 2008, there was rampant construction over wetlands and swamps in Kochi. Since then, there has been some vigilance on how much is built to avoid flooding, landslides and so on. The construction activity has now moved to the cyber park area which is centrally located and more hilly. In Maradu, four waterfront apartment complexes were built violating Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) rules, which were ordered to be demolished in May 2019 by the Supreme Court.[29]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“The urbanisation in Kochi is far less harmful to biodiversity now as compared to other metro cities but harm has been caused in the past for sure. People want to see development and there is positive growth. Since Kochi is a small geographical area, factors like flooding and erosion are risks that are associated with it. Scope for development in this limited space is also less,” said Souparna V, a development professional and project coordinator at Sustera Foundation, who has been working in the climate space and based in Kochi since 2018.

Mumbai: The saturated metropolis

The city, sprawling along the Arabian Sea, has around 149 kilometres of coastline besides an intricate network of watercourse, hills and forests, and wetlands. Vast swathes of Aarey forest, the city’s lungs, have been cleared for constructing car sheds among other projects, the ecologically fragile salt pans have been approved for rehousing slum dwellers from Dharavi and that’s the end of 255.9 acres of them, rivers have been lost to the city with encroachments of all kinds.

A study by Indian Institute of Technology-Bombay found that the urban footprint of Mumbai spread more than the city’s population growth in the four decades from 1972 to 2011. The built-up area increased 4.5 times, from 234 square kilometres to 1,056 square kilometres, while the population grew only three-fold, said the study.[30]

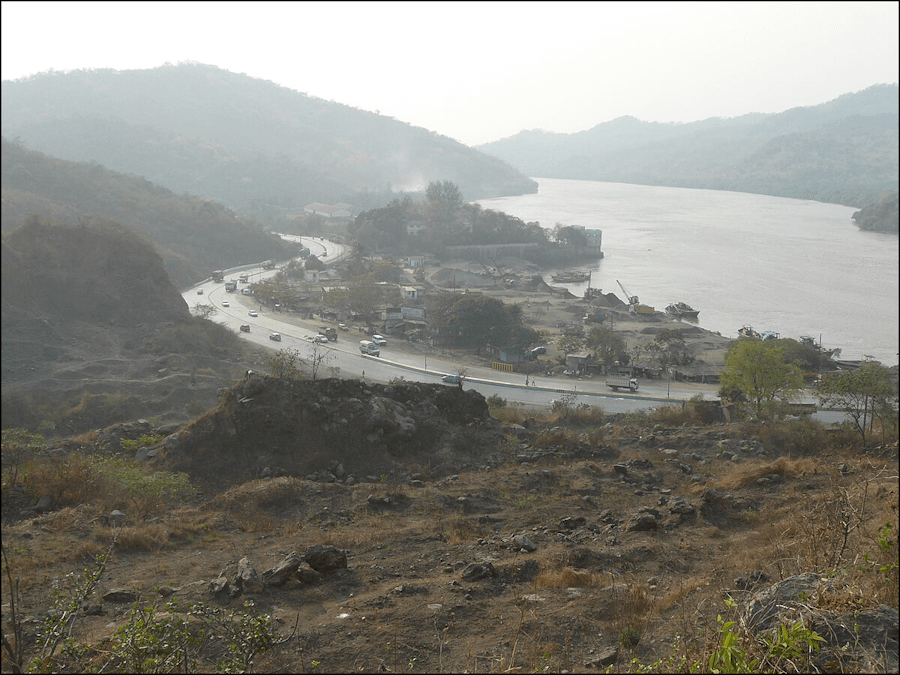

Pune: Natural water networks lost

The rapid expansion of construction has many anecdotes in Pune which lies nestled in the Sahyadri hills and with two rivers flowing through it, is a city with gradually disappearing hillocks and streams. Reports show that Pune’s built-up area has increased from 30.86 percent of the total city landscape in 1999 to 48.50 percent ten years later whereas barren and fallow land area decreased considerably from 36.20 percent to 21.80 percent.[31]

A research, Land Use Land Cover Analysis: A Case Study of Pune City Using Remote Sensing Data, says that there has been a drastic increase in the built-up area in Pune in the last two decades – it has increased from 54.03 percent in 2001 to 63.84 percent in 2020.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Gurudas Nulkar, who heads the Centre for Sustainable Development at the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, lives in a 135-year-old house in the old Sadashiv Peth. “All around our house are large buildings. The old wadas are gone. In the same space, more families are living, so you have to create more parking spaces,” he says of the parking problem in the city.

Pune has seen a glut of construction in the past few years with the metro rail, the controversial riverfront development, river rejuvenation, ring road, multi-level flyover at Chandani Chowk and Pune airport expansion. Vetal Tekdi movement,[32] a citizen-led movement, has been fighting to save the biodiversity-rich Vetal Hills. “The Pune Municipal Corporation is spending Rs4,200 crore on the riverfront beautification project. This is completely absurd,” says Nulkar.

Thane: Fusion of heritage and high-rises

The historically rich city of Thane, adjoining Mumbai, has 27 kilometres of coastline and the 1,000-acre Yeoor forest, an extension of Sanjay Gandhi National Park. The rolling hills, forests, the creek, wetlands and mangroves are slowly getting lost in a maze of high-rises. Known as the city of lakes, Thane now has only around 35 lakes – most of them polluted, neglected and encroached upon.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Thane’s built-up area increased by 27.5 percent between 1995 and 2020, reducing[33] open spaces by nearly 30 percent, wetlands by around 19 percent and mangroves by 36 percent. Once lush green, Thane lost 1,329 trees in 2024.[34] Chirodeep Chaudhuri, well-known photographer and city chronicler, who moved to Thane in 2000, has seen a “manic rise” in the number of buildings. “Just around where I live, it used to be largely factories and industrial areas but they have all been gradually replaced by housing complexes. What’s happening in Thane is not so much about rural land or forest land taken over but industrial plots which were possibly built on forest land at one point,” he said to Question of Cities.

The heavily congested Ghodbunder Road that connects Thane and Mumbai has been seeing more traffic in the past few years – resulting from and fuelling the boom in tall residential towers being constructed.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect, illustrator and urban practitioner, works with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with more than 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she is concerned about climate change and is learning about sustainable development.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons