The experience of Climate Change is deeply gendered and intersectional. [1] What exactly does this mean and what implications does it hold for creating climate-resilient, inclusive, and liveable cities? In this essay, I follow three advances in conversations around gender and Climate Change adaptation. First, how the notion of only women as vulnerable is misleading; second, the variable outcomes of mainstreaming gender into climate action plans; and third, what gender-transformative climate action could mean.

Mainstream discourses on Climate Change and its impacts on people have tended to focus on extreme events – devastating floods, scorching heat waves, ever-strengthening cyclones – quantifying destruction and damages in dollar values and offering an alarming spectacle of precarious lives and livelihoods. Within this, many have demonstrated that women tend to bear the brunt of these impacts [2], left as they are to deal with eroded livelihoods, increased care duties, poorer financial capacities to recover and adapt.

It is only lately that this research and practice has caught onto what gender studies experts have known for a while[3] – that vulnerabilities to climatic risks but also non-climatic shocks and stressors are strongly mediated by an interplay of class, caste, gender, livelihood types, and location. For example, upper-caste women’s material conditions such as concrete housing, better housing locations, and social capital can reduce their vulnerability to flooding compared to men and women from lower castes. Within poor households, as Climate Change makes precarious livelihoods even more uncertain, men can face social stigma and mental distress due to unpaid loans, but women experience higher domestic work burdens, worse health, and intimate partner violence[4].

Such articulations of climate impacts affecting women disproportionately do two things. First, they frame women as victims of Climate Change, as vulnerable subjects to be ‘targeted’ through vulnerability alleviation interventions or as ‘virtuous’ grassroots environmentalists to be ‘rewarded’. Almost two decades ago, Seema Arora-Jonnson cautioned about the implications of this lopsided and somewhat harmful binary of women as victims or inherently virtuous[5], arguing that “generalisations about women’s vulnerability and virtuousness can lead to an increase in women’s responsibility without corresponding rewards.”

Photo: Chandni Singh

Second, a focus on women as vulnerable to Climate Change excludes acknowledgement of male vulnerability, erasing how young male migrants are entering climate-sensitive, poorly paid livelihoods as they move into cities[6], or how older men are left to make sense of a farming identity as farming itself becomes unviable[7]. Thus, the binary of men or women as vulnerable overlooks the intersectional drivers of climate vulnerability, simultaneously disavowing the structural conditions under which women’s vulnerability is constructed and perpetuated, as well as leaving out vulnerable men who are often disadvantaged by caste status, social norms of masculinity, and poor incomes and assets.

‘Mainstreaming’ gender: two steps forward, one step back?

Given this context of differential and intersectional vulnerability, where does India stand? Drawing on global calls towards ‘mainstreaming’ gender into climate policy, India’s national and subnational policy has taken various positive steps towards mainstreaming gender in its National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) and in State Action Plans on Climate Change (SAPCC).

The NAPCC, formulated in 2008, says,

…the impacts of climate change could prove particularly severe for women. With climate change, there would be increasing scarcity of water, reduction in yields of forest biomass, and increased risks to human health with children, women and the elderly in a household becoming the most vulnerable. With the possibility of decline in availability of food grains, the threat of malnutrition may also increase. All these would add to deprivations that women already encounter and so in each of the adaptation programmes, special attention should be paid to the aspects of gender. (NAPCC 2008, page 14)

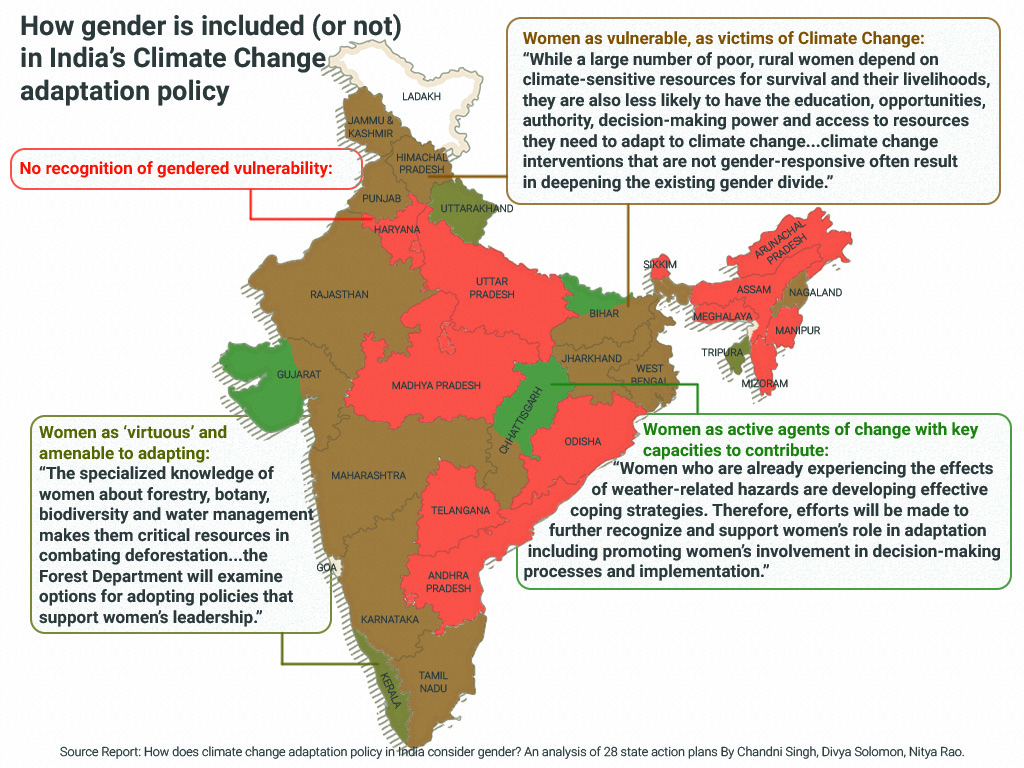

While homogenising all women as vulnerable and not acknowledging intersectional vulnerability, the NAPCC provided states with a national articulation around the gendered impacts of Climate Change. We reviewed 28 SAPCCs[8] to examine how states had gone about formulating this and moving ahead. The study found that most SAPCCs explicitly mention gender as a mediator of vulnerability and adaptive capacity but operationalise it inadequately and unevenly (an important caveat is that all states are revising their SAPCCs currently and the revised ones are beginning to nuance their consideration of gender).

Photo: Creative Commons

Alarmingly, 12 of the 28 SAPCCs did not mention or acknowledge gender, highlighting how sub-national policies on Climate Change have a long way to go. The 16 SAPCCs that do mention gender, do so in a variety of ways and often use multiple framings. Fifteen states still view women as victims of Climate Change, mainly focusing on increased work burdens (time to collect firewood or water) as indicators of this. Three states (Tripura, Kerala and Uttarakhand) swing in the opposite extreme, acknowledging women’s knowledge and societal roles as key for Climate Change adaptation.

Only four states (Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Uttarakhand) speak of women as change agents, as holding power and potential to shape and drive adaptation on the ground. Given that most policies tend to frame women as victims of Climate Change or ‘most vulnerable’, they fail to recognise how women contribute to household adaptive capacities and the reality of intra-household adaptation decision-making which is often cooperative than combative. This oversight erases the substantive evidence on how women determine food and nutritional security, and family wellbeing in households, through direct and indirect labour and care duties.

Illustration: Shivani Dave

All the SAPCCs view gender through binaries of male/female-headed households which masks intra-household heterogeneity, relational gender dynamics and changing masculinities. Fourteen SAPCCs allude to intersectionality by discussing how gender intersects with livelihood opportunities especially in agriculture and forest-based livelihoods; labour divisions; natural resource access and use; and existing deficits such as caste-based marginalisation.

However, worryingly, in all the SAPCCs, gender is equated with women, and women are mostly discussed as a homogenous category. This overlooks the differential experiences of women and men, views gender as fixed, and does not acknowledge underlying societal drivers of vulnerability. Only Nagaland, Chhattisgarh, and Uttarakhand SAPCCs acknowledge that certain men are also vulnerable to climatic risks.

Climate action in practice

While the climate policy space presents a mixed picture on how it is mainstreaming gender, it is instructive to examine the action on the ground. A range of actors and interventions, at different locations and scales, are in play. In India, Climate Change adaptation is happening in various sectors – from heat advisories in informal settlements to improved irrigation efficiency in farmlands, from planned relocation away from coastlines at risk of cyclones to providing risk insurance.

Taken together, these interventions have their own ways of operationalising vulnerability and gender mainstreaming, and there is negligible understanding on whether climate actions in India are helping or hindering gender equality. I piece together some lines of evidence to try and answer this question.

Photo: Creative Commons

Globally, we know that adaptation interventions, or actions to reduce risk to Climate Change, can actually increase gendered vulnerability and deepen inequalities when it is top-down and blind to existing social conditions. Examining about 320 peer-reviewed papers, Professor Joyashree Roy and authors found that[9] “current adaptations aiming to reduce exposure, risks, and vulnerabilities to climate change do not automatically enhance gender equality”; in fact, “without an explicit focus on gender equality and transformative change at project formulation, design, implementation, and monitoring stages, adaptation projects run the risk of reproducing existing gender disparities”.

Replicating this study for cities, we found that several commonly used adaptations such as early warning systems and building risk awareness through public messaging showed mixed effects on the targets of SDG 5 on Gender Equality[10], often excluding women where digital literacy is low, or unable to reach informal settlements and those who are poor. Certain strategies such as urban agriculture interventions do increase women’s agency but may increase their unpaid work.

While there are no studies systematically assessing how current Climate Change adaptation is affecting gendered vulnerability or whether they are helping meet equality goals, scattered evidence paints a mixed picture. In rural areas, adaptation interventions assume households as male-headed and unchanging, with techno-infrastructural measures prioritised. The increasing focus on ‘climate-smart agriculture’ and digital media to achieve this potentially exclude certain men and women – for example the landless, the illiterate. Some notable exceptions are more gender-sensitive climate advisories by MSSRF in Tamil Nadu[11] or SPS’s Women-Led Climate Resilient Farming[12] model which focus on federating women farmers by focussing on micro-irrigation.

In cities, gendered outcomes of adaptation are mixed. While migration, a strategy used to diversify risk, can improve household incomes and investments in health and education, they often lead to lower quality of life for women, reported in terms of decreased leisure, higher unpaid work, and loss of place and home[12]. Women in cities also face non-climatic barriers to equality and integration[13], which then get exacerbated when floods and droughts hit. Some experiments are however showing promise – from MHT’s women-led heat management in informal settlements in Ahmedabad[14] to women-led urban farming enterprises[15] that are providing income and helping recycle wet waste in Bengaluru and Pune.

Tentative steps towards gender-transformative action

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in 2022 stated with high confidence that “there are very few examples of successful integration of gender and other social inequities in climate policies to address climate change vulnerabilities and questions of social justice”. This should serve as a reminder that the climate actions we are putting in place are not addressing gendered vulnerabilities, and in some cases are exacerbating it by paying lip service to gender equity concerns.

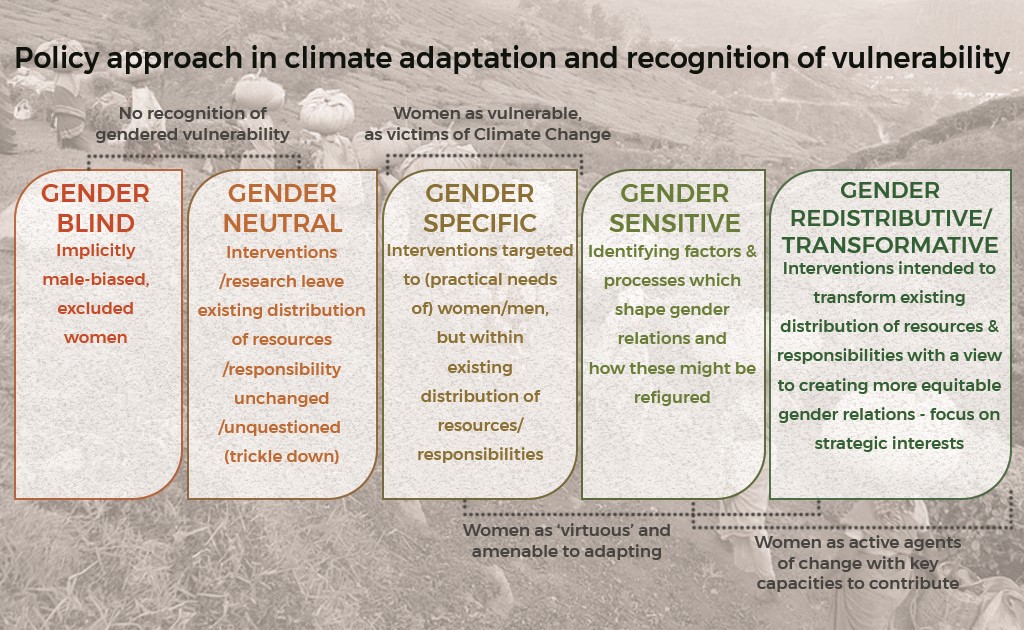

The research on gender and Climate Change has matured to move away from being gender-blind to targeting women (gender-specific) and increasingly calling for gender-transformative climate action. Such a transformative approach moves away from “merely emphasising the inclusion of women in patriarchal systems, (to) transforming systems that perpetuate inequality can help to address broader structural inequalities not only in relation to gender, but also other dimensions such as race and ethnicity” (IPCC 2022).

Adapted from Singh et al. 2021.

Illustration: Shivani Dave

Mainstreaming gender has served a purpose in making us acknowledge gender in Climate Change but to assume it will lead to gender-transformative change is placing too high a burden on such a weak mechanism. As Indian states revise their SAPCCs, and greater attention and investment flow into climate adaptation, we must complement the mainstreaming approach with one that focuses on systemic change.

One that makes gender-disaggregated data, gender budgeting, and gender expertise in developing the policy, minimum requirements in all SAPCCs. One that uses meaningful ways to include and prioritise voices of grassroots organisations, men and women in adaptation planning and decision-making. One that learns from other successful movements and vehicles of transformation such as women’s rights and LGBTQIA+ collectives. And, finally, one that moves current adaptation actions from a women-targeting approach to a mix of gender-specific and gender-transformative approaches.

There is work to be done.

Dr. Chandni Singh is a Senior Research Consultant at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements, and works on issues of Climate Change adaptation, differential vulnerability, disaster risk and recovery, livelihoods transitions, and rural-urban migration. She was a Lead Author of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC’s) Assessment Report 6 last year, is an editor to journals on Climate Change, and assessed how Indian states are mainstreaming gender in their climate adaptation policies.

Cover photo: Creative Commons