Placemaking uses the invaluable knowledge provided by communities from their lived experiences to transform public spaces where they live, into places they can frequent and spend time. It is a democratic process that involves the people who occupy the place by giving them the agency to decide how they want to design it and make it more meaningful in their lives.

Placemaking holds the power to transform derelict and unused spots into public spaces that brim with life, the kind that invite their users to use the space for rest, work, and recreation. The public spaces, however, need to be inclusive to truly belong to the public. Creating inclusive spaces that serve the needs of a diversity of stakeholders can be a challenge. But placemaking is not only about creating material places as typology; it is a process which must involve people. It is an assertion of one’s right to the city.

So then, how does placemaking translate into practice? Question of Cities brings you stories of placemaking from across the world that have used a range of approaches from art and design to public participation and transformed everyday spaces into public spaces that people can share, cherish, and feel comfortable in.

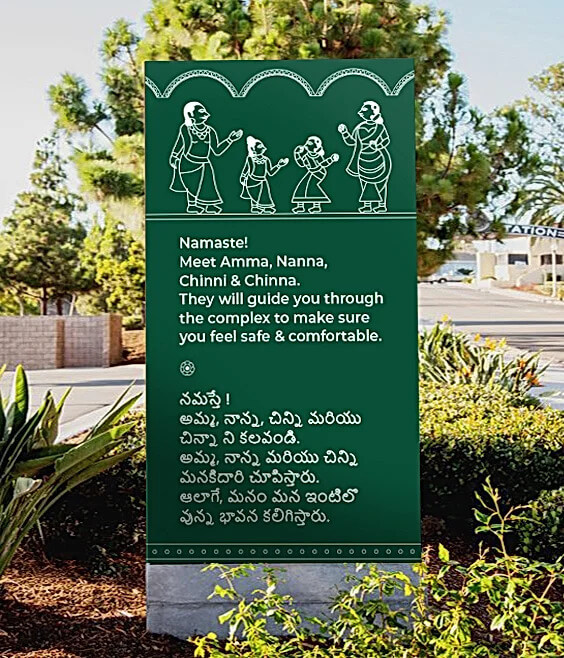

Photo: LOCAL

POCSO Court, Warangal (Telangana)

A brand and graphic design studio based in Mumbai, LOCAL, incorporated a home-grown art form into their placemaking to create the sign system for a POCSO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences) court in Warangal, Telangana. The court sees children and families in distress do the rounds of the court. Roshnee Desai, founder of LOCAL, said, “The brief was to create a signage that spreads a sense of calm in a space that makes you feel stressed and intimidated. It’s such a sensitive topic. You’re in a court. How do you make sure you’re not patronising while helping someone calm down and not feel more intimidated?”

One of the briefs that Desai gave to her team was that when children go to places like Disneyland, they see signage that’s designed to make them feel excited — it tells you how to feel about the space. The idea drove this project. The team chose to use elements of familiarity. Tapping into local art, they used the traditional Cheriyal dolls on signages. Verbal and colour language was designed keeping in mind the familiarity of these dolls for the people. “We introduced nana (father), amma (mother) and chinni (the girl child). Chinni became the young girl from the sign system who would guide one around the court to make people feel safer,” she explained.

Desai says that the team has tried to make it adaptable to the signage needs of POCSO courts across the region. She adds that the project received positive feedback from the public as well as the judicial community, thereby forming a possible template for it to be emulated in courts across the country.

Photo: Spandan Odisha

Soak pits of Penthakotta Puri, Odisha

The residents of Penthakotta fishing settlement in Puri depend on the sea for their livelihood. The wastewater from the homes in this area runs through open drains from the water sources to the sea that inconvenience residents. Spandan, a local NGO, has been working for WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) projects with the community. They had started building soak pits that would direct the water from the open drain to a soak pit covered by seacoast weeds.

The NGO won Water Resources India’s (WRI) The CityFix Lab: Accelerating Access Prize for this which meant it would get WRI’s support to execute the project. Rajeev Malagi, safe access and public space expert from WRI, said, “After interacting with the women self-help groups of the community, that shared ideas to add seating spaces and areas for drying fish, we helped Spandan to come up with solutions that were nature-based and climate-resilient considering that Puri is prone to climate events.”

With the help of the community, they built pits lined with plants whose roots purify the water. They used tyres and sandbags to build seating and fish-drying areas. The walls of the soak pits were also painted by the locals to make them stand out. Malagi says, “This was a pilot project for which the support of the local community was very important. There are 19 such spots created as part of the pilot. Spandan and the local community received support from the local corporator but the grant was entirely utilised by the community.” On the absence of a tangible process of demonstrating the impact of such public places, he said, “It was important for us to show the government what works and what doesn’t for the city to be able to take this forward.”

Photo: PLURAL

SB Somani Park, Cuffe Parade, Mumbai

SB Somani Park at Cuffe Parade in Mumbai, originally known as Dharya Ground, a triangular shaped piece of sea-facing land with the World Trade Centre to its east, a slum to its south and a parking lot to its north — also a dead end — made the area a defecating ground and as a hub of anti-social activities. PLURAL, an organisation that works in participatory planning, mapping, urban design and conservation, came across this space during the mapping of civic wards. They had heard discussions about parcels of land that are not optimally used.

Oormi Kapadia and Jasmine Saluja, founding partners of PLURAL, put forth a plan, which they had worked out with the Colaba Residents Association, to the local corporators who, as Kapadia said, were eager to execute it. They also presented the plan to the slum dwellers who asked, “The watchman never allows us in. What will you do with our suggestions?” The corporators promised them that they would be allowed inside during the park timings.

The park has been built with the support and suggestions of what Kapadia called ‘floating stakeholders’, who are the drivers from the parking lot and the house helps from Colaba and Cuffe Parade who used this space to rest. It is now a space where several groups of people conduct activities. “You can see children from the slums and the high-rises playing together. People from World Trade Centre come here to have lunch or conduct short meetings,” Kapadia said. Added Saluja, “We had envisioned the amphitheatre as a safe space for the youth of the locality to conduct role plays, group presentations and even shoot videos without making it look unsafe and we see that happening now.”

The main challenge that PLURAL faced while doing this project was executing work beyond the limitations of the terms laid down by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) which only allows certain kind of materials to be used. The BMC has an outdated schedule of materials which limits choices for designers. As a result, within a year of the park’s opening, the equipment lies broken. The process of engagement with different stakeholders and the community is not defined under the Garden Department of the BMC. Referring to placemaking and democracy, Saluja says, “In today’s context, placemaking is one of the democratic tools to contextualise public spaces. Using this, we designed the idea of a melting pot of different communities within Mumbai, where chance encounters happen between slum dwellers and residents living in tall towers in Cuffe Parade. There is more tolerance and acceptance of each other while using these curated spaces.”

Photo: Elekes Andor/ Wikimedia Commons

NDSM Wharf, Amsterdam-Noord

The NDSM Wharf built in the 1920s is a shipyard in Amsterdam, on the north-western side of the city, across the IJ river. It houses defunct factories and buildings of an era when ship building was a huge business. The site became defunct between 1965 and 1980 after shipbuilding declined due to the oil crisis and rising costs of labour. Young artists started squatting in the buildings in this area in the 1980s to hold workshops, play music, make murals, hold concerts and church services.

In 2000, when the government wanted to develop housing and public spaces in the city, it wanted to redevelop the wharf but the community resisted this. After negotiations, it was decided that the inhabitants of the wharf would continue there for ten years while the government carried out reconstruction work. At the competition held to select the best plan for the renovation and preservation of the wharf, the squatters, who had organised themselves into Kinetisch Noord Foundation, won it. They now had the opportunity to do something with the 15 million Euros that the local government was going to invest from 2000 to 2015 to repair the old buildings and reenergise the area.

In 2015, the Foundation was able to buy the entire NDSM building — in which there were 85 studios run by creative entrepreneurs — from the government of Amsterdam. After years of transformation and struggle by its latest creative inhabitants who started settling here, the area has turned into a vibrant, safe, and meaningful hub for artists, chefs, and tech start-ups. Amsterdam-Noord, as it is called, put placemaking into practice.

South Duke Street, Lancaster

In 2019, the city of Lancaster launched their engagement platform to consult their residents on how to make their South Duke Street Mobility Project safer and more community-friendly. The plan to improve pedestrian infrastructure and streetscape design along South Duke Street came from the citizens who requested safe, walkable, and accessible streets in their neighbourhood as a part of the Vision Zero Action Plan adopted by Lancaster City Council.

Research found that slower speed limits, more lighting and designated bike lanes could help make the street more people-friendly. Lancaster’s Department of Neighbourhood Engagement launched a platform called ‘Engage Lancaster’, inviting suggestions from citizens. They uploaded their own map layers to display local information and landmarks. The citizens would then have to help the city mark the areas that needed the most improvement. This included spaces where they needed more greenery and lights, sidewalks and crosswalks, intersections that were prone to speeding. The department also carried out 1,000 paper surveys across landmarks in the city. The project used maps to help people move towards their demand for a pedestrian and vehicle-friendly corridor.[1]

Photo: Rithvik Reddy

Life at the Intersections in Chicago, USA

Artist Molly Costello, who grew up in Andersonville, Chicago, was hired by the Andersonville Chamber of Commerce in association with Chicago Association of Realtors to make the mural ‘Life at the Intersections’ on the south wall of The Clark in the locality. Costello interviewed 77 local residents and business owners who were an inspiration for the piece which celebrates the diverse lives that overlap on the bustling streets of the community. The mural also highlights the neighbourhood’s LGBTQIA+ and activist legacies in the hope that it will help reflect on inclusion, safety, wellness, mutual support and care.

After Costello’s research through interviews, questionnaires, museum visits, and phone calls, they started writing and sketching ‘Life at the Intersections’ wanting to emphasise the idea communities can thrive when approached with an intersectional lens.

Costello writes on their blog, “I found myself asking what does it mean to “celebrate diversity” and who does that benefit? Does a project like this help create a safer and more inclusive space for all Black, Transgender and POC (person of colour) community members and visitors?” While adding that there is no short answer to this and that genuine community safety looks like so many small and large changes to our culture, they add, “It is my hope that this mural is not seen as a celebration of something achieved but rather as an invitation to our future together and a joyful recognition of the work that is ahead of us, work that is rooted in collective care and affirms the inherent worth of all Andersonville residents.”[2]

Cover photo: Amsterdam-Noord by Ruben Hansson/ Unsplash