The famous Oxford Street in London, known for its high-end retail shops, could soon be traffic-free. The proposal to pedestrianise the iconic street has been recently rebooted after mayor Sadiq Khan took inspiration from Times Square in New York. The transformation aims at increasing footfalls, creating new jobs, and boosting growth in London and across the UK.

This is an example of how cities around the world have carried out radical redesigns and repurpose of public spaces – by breaking barriers of conservative urban planning, class structures and the economy. Some have experimented with innovative and bold ideas to change spaces, housing, transport and the way people use spaces.

Redesigning streets and precincts to be car-free is not necessarily new urban reimagination but, in the era of intensifying impact of climate change such as high air pollution and rising emissions, it has gained new traction. Cities were not built for the climate era but some of them have broken the old barriers to make them more ecologically sustainable and inclusive. The common templates to redesign include placemaking, walkability, and resilience.

Aspern Seestadt, Vienna

Vienna’s Aspern Seestadt, one of Europe’s largest urban development projects, blends old city concepts with smart city ideals, and importantly takes into account women and their needs. An old, unused airfield has been transformed to build Aspern Seestadt, in a thriving community spread over 800 acres. When completed in 2030, it will be home to over 25,000 people and 20,000 workplaces.[5]

“Eva Kail, urban planner, has shaped life in Austria’s capital for three decades and helped develop gender-sensitive innovations for parks and gardens in Seestadt, creating more options for traversing the space and encouraging visibility. All the streets and plazas here are named after women — Janis Joplin Promenade, Hannah Arendt Platz and Ada Lovelace Strasse, to name a few. But Kail pointed to plenty more examples of the gender-conscious urban planning that she spent 30 years researching and implementing in Vienna: Wider sidewalks for strollers, safer parks with more benches for resting, more services and amenities within walking distance,” states this NYT piece.[6]

Spatial planners Astrid Krisch and Johannes Suitner, in their analysis of Aspern Seestadt[7], call “the switch from government to governance” in city planning. The priority is nurturing the emergent ideals rather than dictating them.[8]

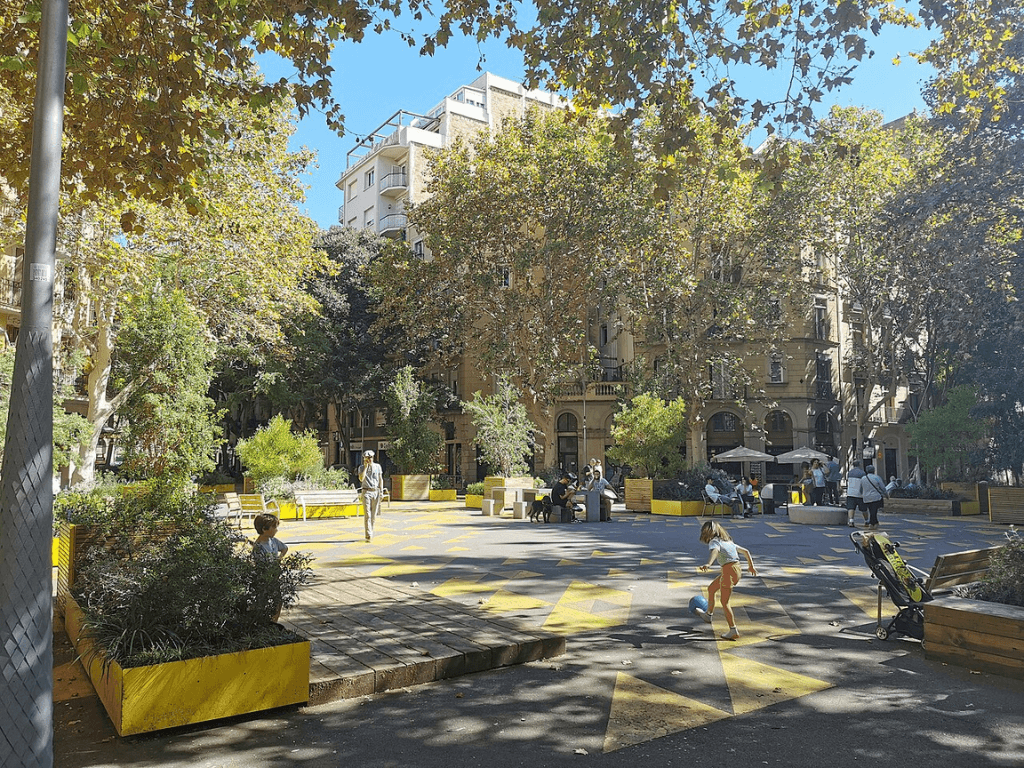

Barcelona, Spain

The Barcelona superblock, proposed as a sustainable urban neighbourhood transformation strategy, focuses on reducing space allocated to cars, allowing for alternative uses to enhance liveability and sustainability. The urban design experiment shows us how neighbourhoods can reclaim streets as public spaces.

“When architect Salvador Rueda first proposed the concept of superblocks in 1987, he called them “super-manzanas”. Manzana means apple in Spanish and referenced the shape of Barcelona’s blocks. They are not squares like most blocks in grid-laid cities such as New York but look more like octagons with edges smoothed. This creates more space between them, and increases road safety. The Superblock is now not merely a space. It has become an approach. Adopting the Superblock approach means putting people at the centre, literally,” explains this article.[9]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Oslo’s city centre is people-centric

Norway will soon introduce new measures which could further limit the number of cars in its capital. The country, which is already one of the leaders in electric car sales, plans to fully ban petrol-powered cars from next year. Oslo’s effort to return the city centre to its residents can be considered a great example of how ambitious policies in cities can directly benefit residents.[10]

“In 2019 the Norwegian capital removed more than 700 parking spots[11] from its downtown area and replaced them with bike lanes, plants, tiny parks, and benches. Oslo is one of a few cities hopping on the car-free trend[12], and it’s been working toward this goal for a few years, but 2019 marked the start of a car-free downtown. The effort doesn’t only help people get around without traffic, either; it improves air quality, helps fight climate change, and enhances the quality of life,” says this essay.[13]

Stockholm, Sweden

While Paris works with a 15-minute radius and Barcelona’s Superblocks[14] with nine-block chunks, Sweden’s project operates at the single street level. Called Street Moves[15], the initiative allows local communities to become co-architects of their own streets’ layouts. “With workshops and consultations, residents can control how much street space is used for parking or for other public uses. It’s already rolled out experimentally at four sites in Stockholm, and three more cities are about to join. The ultimate goal is hugely ambitious: A rethink and makeover of every street in the country over this decade, so that ‘every street in Sweden is healthy, sustainable and vibrant by 2030’,” according to Street Moves.

While municipalities may provide their own versions of this toolkit, the design of each street is based on workshops and conversations with local residents — including school children. Streets near transit stops might favour more bike parking, while those with cafés could opt for more seating. Some units might emphasise tree-filled planters, others play spaces. Piece by piece, these installations can transform streets into sites of sociability and mixing, joining up steadily into neighbourhoods where the space used daily by residents extends little by little out into the open air, explains the news report in Bloomberg.

“A plan piloted by a Swedish national innovation body and design think tank focuses on the spaces just beyond the doorstep are ideal places for cities to start developing new, more direct ways of engaging with the public. Sweden’s streets, Vinnova says, can become ‘an innovation platform for rapidly and powerfully addressing climate resilience, public health and social justice combined’”.[16]

Mexico

Programa de Mejoramiento Urbano[17], or P.M.U., the urban improvement program created in 2018 by Mexico’s Secretariat of Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development (SEDATU)[18], is one of the largest public construction programmes in the country. While major government initiatives in the past had focused on providing housing, schools and other basic needs to marginalised towns, civic spaces accessible to everyone had long suffered from a lack of resources, said Román Meyer Falcón, secretary of SEDATU. “These are neighbourhoods that for decades have not had a field, a sports facility, a public market, a plaza, a road,” he said.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The P.M.U. has so far completed about $2 billion worth of public buildings and community infrastructure in which towns applied for help through a rigorous process; selected architects and designers — many highly regarded, smaller offices — have already completed about 1,035 projects, often in remote areas, with some winning international architecture awards. “Another key strategy: Making places that pull people in. Plazas and courtyards contain feathery mesquite and blue-green palo verde trees and employ brickwork that blends with the buildings themselves. Partial walls are inviting, and limit the need to pay for (or fix) heating and air conditioning, while keeping people inside safer from crime thanks to increased visibility. Lattices, inspired by traditional Mexican screens called celosías[19], provide privacy while permitting breezes and light. Just as important as the practicalities, the buildings are designed to build social connections. They are created as places to stay, and be proud of, in locales that are often regarded as pass-throughs, overshadowed by the ever-more-tumultuous border and what’s on the other side,” details out this NYT article.[20]

Lima, Peru

A unique people participatory project, Ocupa tu Calle, in Peru’s Lima transformed neglected spaces to encourage public use. “Started in 2014, Ocupa tu Calle[21] is an online platform where Lima’s residents can register neglected or abandoned public spaces and propose low-cost ways in which they can be improved — by turning empty lots into small-scale plazas, for example, or by refurbishing parks that have fallen into disrepair. Approved projects are coordinated by the NGO Lima Cómo Vamos, which works with community volunteers, civil society partners and local government bodies and raises funds,” states this piece.[22]

Lucía Nogales, who is the general coordinator of Ocupa tu Calle (Occupy your Street)[23], terms it as Citizen Urbanism — a concept they are promoting and defining alongside other organisations in Latin America[24]. The series of projects, people, and initiatives claim an alternative urban model, forged from the knowledge of social dynamics. “A model that applies innovation, participation, and collaboration tools for the design and planning of more equitable cities; thought from, for, and with people, including them at all levels of decision-making,” she says in this feature.[25]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Paris, France

Paris-born and based designer Stéphane Ashpool has teamed up with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to unveil three artistic sports installations. “Paris is Your Playground” celebrates the joy and spirit of the city in Olympic mode by reimagining everyday street furniture as opportunities for the community to play sport.

“Taking their design inspiration from childhood games and making it for people to come together and play sport, the three pieces turn street furniture into beautiful playable sports installations. A street lamp has been transformed into a basketball hoop and a compact volleyball court, whilst a bench also becomes a football goal. In the spirit of the Olympic Games, the interactive installations, which blend sport and city decor, invite people to meet and engage in sporting activities, fostering a sense of community and encouraging movement,” explains this essay.[26]

New York City, US

Cities existed before cars. This is what Janette Sadik-Khan, New York’s transportation commissioner between 2007 and 2013, was out to prove when she set out to work on a bold idea of pedestrianised Times Square.

Amid opposition, she transformed the busiest and least pedestrian-friendly space, Times Square, into a car-free space. “You have to move quickly, because people don’t believe that cities can change. If you show them what can happen, even if it is by using tactical urbanism, painting a street one night, the city mutates, it becomes something else. It reduces anxiety about change. And the fact of it being temporary makes people relax. It is understood that little has been invested, and perhaps that makes the perception of change less than it really is,” says Sadik-Khan in this article.[27]

Cover photo: A street in Barcelona. Credit: Wikimedia Commons