Among the many fond memories of growing up in Bhubaneswar, then one of India’s planned new towns after independence along with Chandigarh and Gandhinagar, is one of spending long evenings with the family as the cool southern breeze gently swept across the forecourt garden of our bungalow. My sisters and I spent time outdoors climbing trees or running and cycling with friends. There was a sense of the open, a vastness, beyond the home.

Bhubaneswar had become the capital city of Orissa (now Odisha) with a population of barely 25,000. Moving to Mumbai, then Bombay, to join the Sir JJ College of Architecture in 1972 was overwhelming given the city’s size, complexity and congestion even then. Besides igniting the spark for human rights and justice movements, the wide chasm between the two cities brought home to me the learning not always given in classrooms: Spaces matter, how they are built matter too because they impact people and ecology.

The story of Bhubaneswar tells us that planning a city is best not done from a top-down perspective and must include participation of people, that master plans which do not integrate what already exists – such as the old temple town – are overrun by time, and planning which does not take into account local ecology is not sustainable in the long run.

Bhubaneswar was imagined more than a decade before independence though it became one of the post-independence new towns. Orissa was carved into a separate province on April 1, 1936, from the administrative units of Bihar, Bengal and Madras; a new Bhubaneswar was to be its capital. However, the city’s planning started only after April 13, 1948, when the then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru laid the foundation stone with his words: “…Bhubaneswar would not be a city of big buildings for officers and rich men without relation to common masses. It would accord with our idea of reducing differences between the rich and the poor”.

Nehru’s noble vision did not fully materialise in the master plan prepared by German-Jewish architect Otto Koenigsberger, who was forced to leave Germany under Adolf Hitler and secured Indian citizenship in British India. He also drew up the master plan for Gandhinagar. With Le Corbusier and his team of largely international architects planning Chandigarh, the imagination of India’s modern new cities – and the realisation of Nehru’s vision through architecture – was in the hands of foreigners.

From Ravi Kalia’s book Bhubaneswar: From a Temple Town to a Capital City

The master plan

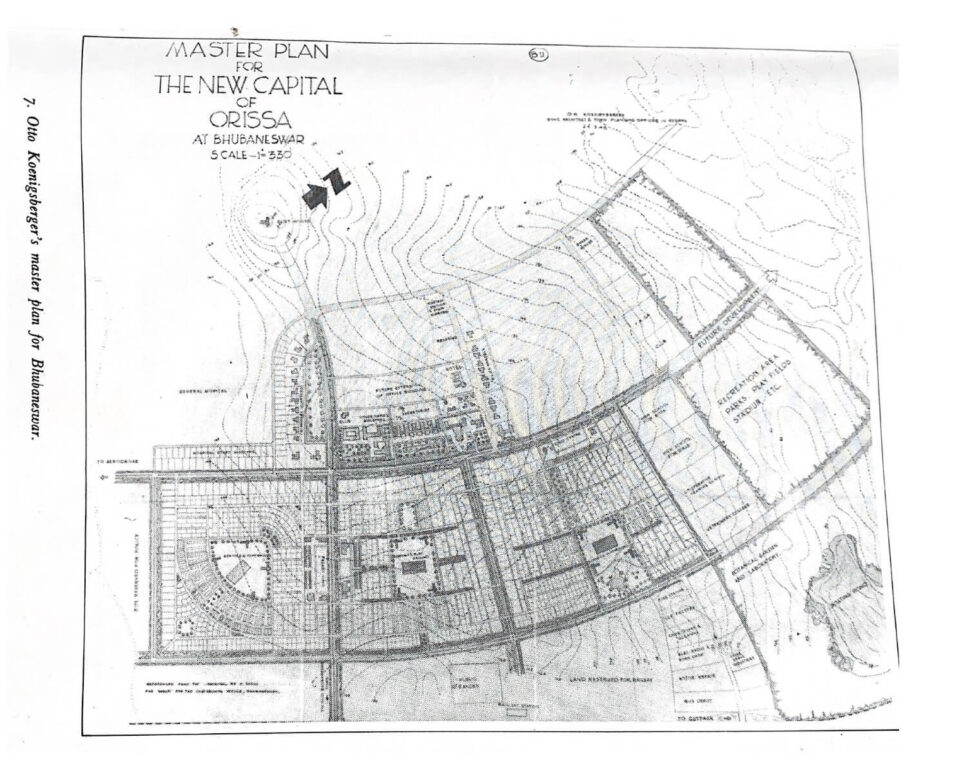

Bhubaneswar’s master plan, contrary to Nehru’s words, was based on hierarchical grids with differing sizes of houses and amenities for various classes of government officials apparent in the layout of neighbourhoods. Such spatial segregation, seen also in Chandigarh’s master plan, has been ingrained in the popular psyche through policies. Unlike his keen interest in building Chandigarh, Nehru paid scant attention to Bhubaneswar – a reflection of the political importance of a Chandigarh after the Partition but also a sign of north Indian dominance. This was carried forward by many including Prime Minister Narendra Modi when he chose Varanasi as his national political constituency; the temple town added to his Hindutva icon image too.

For Bhubaneswar, Nehru’s apparent disinterest and paucity of funds were a blessing in disguise. It meant relative independence for Orissa’s decision makers, including social leaders, to establish an independent Odia identity along with the state. Planning and building the city, including defining the architecture of buildings, became more participatory – though limited to government officials – than in Chandigarh.

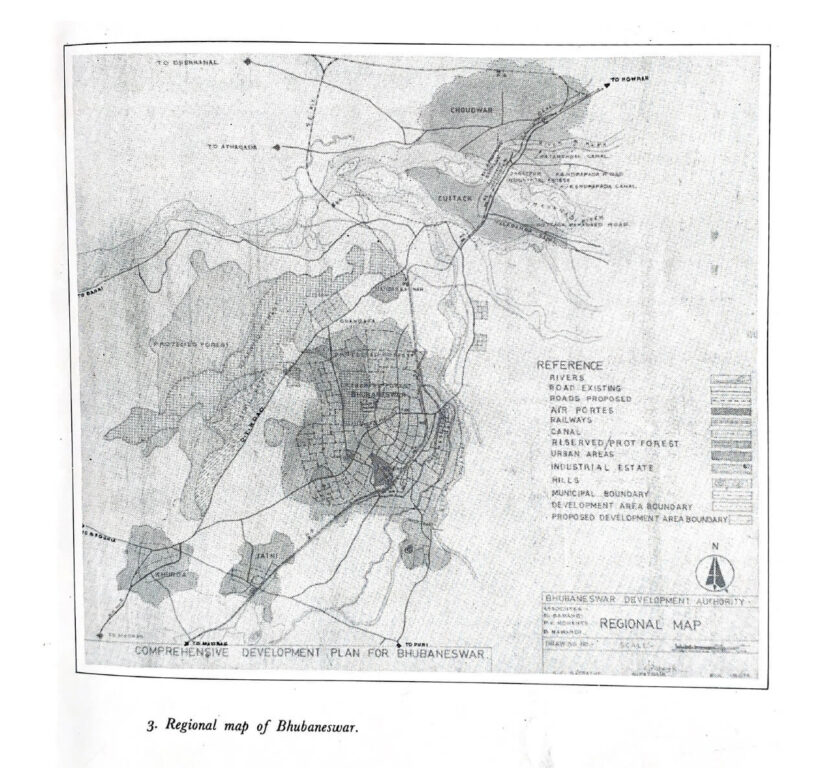

Koenigsberger, invited by the Orissa administration in 1948, was present when Nehru laid the foundation stone. However, he was presented with the site for the new city, away from the old temple town. The siting had begun before his appointment and years before India was independent. The selection process was long and contenders many – Cuttack, the then capital of Orissa; Chowduar, an adjoining industrial town; the temple town of Puri; Angul, Khurda and Barang besides the temple town Bhubaneswar. Eventually, the selected site was between the old temple town and Cuttack, away from temple town culture and Cuttack’s parochialism.

Photo: Subhashish Panigrahi/ Creative Commons

Koenigsberger’s neighbourhood unit idea

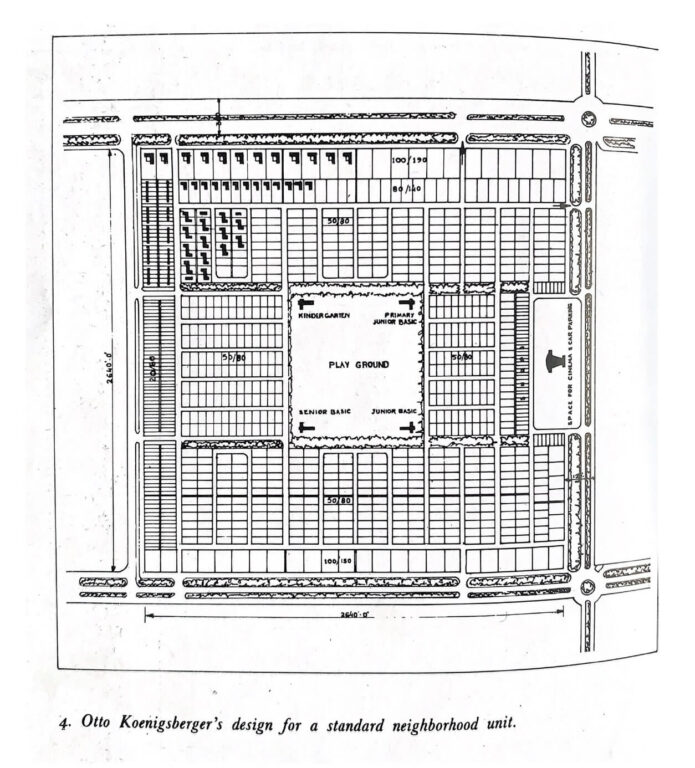

The basis of city planning, in Koenigsberger’s imagination, was the neighbourhood unit like a sector. He had worked with this concept earlier in Jamshedpur. A neighbourhood unit was an average 150 acres square with 1.2 kilometres on each side. Houses were organised in clusters around the open spaces in each unit to allow the cool southern breeze to waft across them.

Koenigsberger believed that the unit would be “an attempt to transplant into the city one of the healthiest features of country and small-town life.” Each unit was self-contained with amenities like schools, dispensaries, shopping, and entertainment centres, all of which could be accessed on foot. Such units, he thought, would enable people to “understand their civic responsibilities much better than a large amorphous city.” Multiple neighbourhood units, connected by a public transport system, would form the city.

If Bhubaneswar was to expand, units could be added. This linear approach, he argued, would make for easy growth and an efficient transport system. He also proposed area planning in which different zones would have industry, recreation, shopping, housing, and transportation. Life in Bhubaneswar’s neighbourhood unit meant social relationships were forged across the usual caste-religion boundaries, people developed a sense of community, and an attachment to their neighbourhoods. This deeply influenced me. It evolves well into neighbourhood-based urban planning in large cities enabling people’s participation and deepening democratic processes.

People and nature

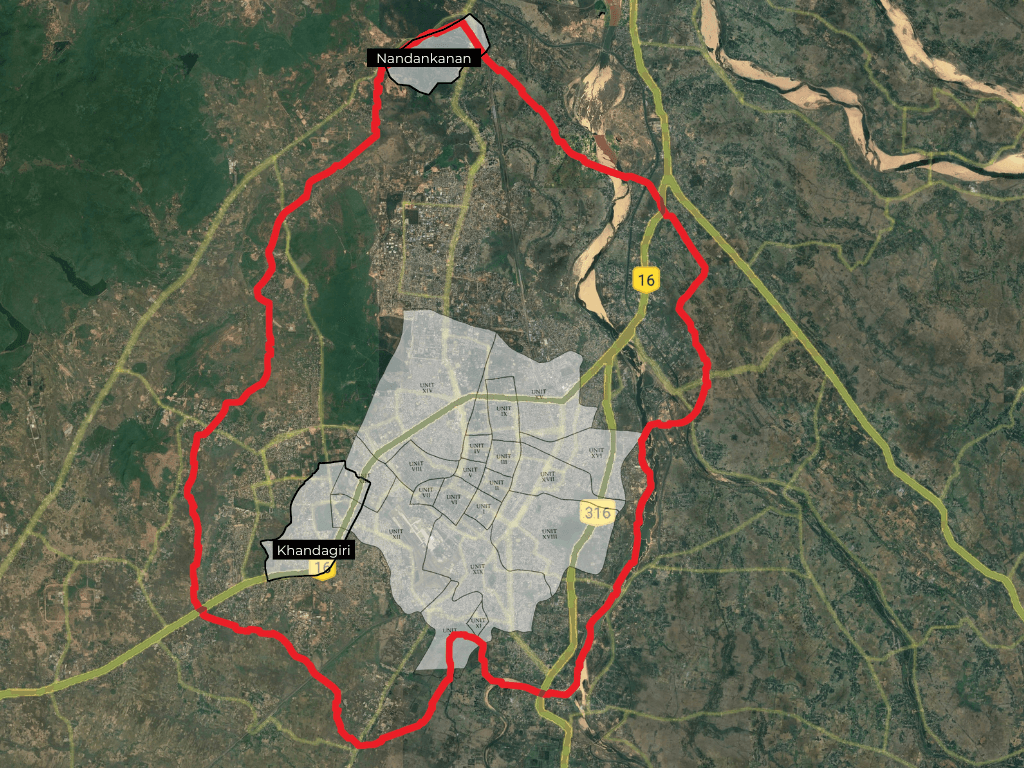

The first six units were the oldest in Bhubaneswar. My father, an anthropologist heading the Tribal Welfare Department of the state government, was allotted a bungalow in Unit-III. The Capital Complex – comprising the Secretariat, Assembly Hall, Accountant Generals (AG) office among other institutional offices – was in Unit-V. Koenigsberger’s plan had envisioned many units, but the first phase was limited to six. Subsequently, 12 or 13 larger units were added. The city later expanded far beyond these units, almost upto Cuttack, making them twin cities. On the opposite side, vast areas have developed too.

Koenigsberger’s master plan imagined all houses in the units to be single-storied which would be favourable to the Indian way of life and climate. Every house had its forecourt garden and a rear yard. Our bungalow too had a large garden in the front and a walled courtyard at the back useful for household work. Away from the house, in the farthest two corners, a toilet and a bath were separately located. There was a large guava tree in the centre of the courtyard which helped keep the house cool. My sister and I would climb it for the fruit. The front had a seasonal vegetable garden with maize, brinjal, okra, and cabbage.

All the bungalows had front and rear courtyards – though their sizes varied – with abundant vegetables, fruits, and flowers. We developed a symbiotic relationship with farming, and learnt how local ecology shaped lives and buildings. In Germany, Koenigsberger had been deeply influenced by his teacher Bruno Taut, an architect with a deep commitment to social architecture and an early member of the Garden City Movement. Undoubtedly, these reflected in Koenigsberger’s master plan.

Please note: The map is a basic overlay of the sketched historical map on the present day Google Earth aerial imagery and hence is not entirely accurate.

Koenigsberger’s city of privilege

Koenigsberger proposed that Bhubaneswar would be a linear city; from a planner’s perspective, achieving “unity” in planning was more possible in a linear pattern than in a radial plan. In fact, he opposed radial planning because he believed “it will never result in useful towns which are pleasant to live in”. His linear city plan for Bhubaneswar relied on one main traffic artery to which individual neighbourhood units would be attached.

Besides the arterial road, he proposed seven types of roads – pedestrian walkways within units, parkways in recreational areas, bicycle paths across various units and areas, minor streets connecting houses, major motorable housing streets connecting the minor streets, main roads between neighbourhood units and workplaces. Walking was to be the predominant mode of mobility within units. Koenigsberger planned shopping squares “not shops along the various streets, accessible from the main roads but at the same time clearly separated from them, so that fast traffic can move undisturbed, and people can buy their provisions at leisure without danger of being run over”.

His brief was to prepare a master plan to accommodate the new bureaucracy and the emotional needs of Odias. Bhubaneswar was, therefore, a largely administrative town. “Koenigsberger viewed the new city of Bhubaneswar as an autonomous body, having its own law and jurisdiction, political independence, right of self-determination, and an organised sense of communal relationship along secular lines,” writes Ravi Kalia in his well-regarded book Bhubaneswar: From a Temple Town to a Capital City.

Koenigsberger had proposed that the government publish his plan calling for public participation, but it was not put into the public domain. “The planning of the new capital of Orissa requires popular collaboration…It is therefore, suggested that the Master Plan be published with an appeal for constructive criticism and practical collaboration…No substantial improvement can be possible unless mass public opinion, is roused in favour of responsive clean civil administration and civic consciousness among all the people,” he observed. It is not clear who he imagined as the public; the plan was circulated only amongst government officials.

This is emblematic of planners and architects across India who, individually and collectively, have failed to influence social change despite their discipline being a democratic tool of social change. Planning and design have become a narrow, timid service to the “client” alone. Even in public projects, administrators and politicians decide; people’s voices are rarely considered necessary. This is most glaring as free-market forces assume control of public resources in a development paradigm which disregards natural ecology.

From Ravi Kalia’s book Bhubaneswar: From a Temple Town to a Capital City

The plan and the city

Koenigsberger and the state government had conflicting visions for Bhubaneswar. The 1948 plan, credited to him, underwent several iterations with many officials influencing changes. Soon after he accepted the Bhubaneswar offer, he moved to New Delhi to assume a role in the union Health Ministry and his involvement in Bhubaneswar tapered. Julius Vaz, chief architect of the government who was actively collaborating with Koenigsberger on the master plan despite their differences, then played a larger role and designed prominent buildings including in the Capital complex.

The first six neighbourhood units developed in accordance with the master plan were expanded to 12-13 additional units. These had a larger footprint each than what Koenigsberger had proposed as a model unit size. His ideals of a neighbourhood unit were compromised as engineers from the Public Works Department (PWD) determined the expansion. Interestingly, M.P. Kini, a senior draughtsman under Vaz had said, “We had too much government influence. There was no Le Corbusier-like person in Bhubaneswar”.

The Bhubaneswar plan, therefore, had many voices but within the government; none from the public. But cities grow beyond a plan. This is true of Bhubaneswar too. The city expanded in all directions engulfing its peripheral villages and agricultural lands, led by more government agencies such as Bhubaneswar Development Authority (BDA) and Orissa Housing Board besides the PWD. This radial expansion shelved Koenigsberger’s linear city planning idea. The new areas are not even referred to as units but identified by their names – Sahidnagar, New Town, Nuapally and so on.

Even his ideas of open spaces, market location and the provision of other social amenities were not followed. Land use and building activity in these areas has meant high-cost and unaffordable mega housing complexes, corporate-run hospitals and schools, even universities, but very little public open spaces and accessible amenities for the less privileged who are a substantial section of the city’s population.

Learning from Bhubaneswar

The city’s planning narrative – a master plan by a well-known planner, implemented by politicians, bureaucrats and engineers, and little to nothing of people’s participation – is now familiar across India. Even when people’s participation is sought, it is perfunctory. However, this is possible if the concept of neighbourhood unit – the basic brick in Koenigsberger’s master plan – was embraced and people allowed to shape spaces within their neighbourhoods. The concept of Koenigsberger neighbourhood unit expanded to neighbourhood-based city planning is possible – even necessary today.

Bhubaneswar today ranks as the best Smart City in India. It is a well laid-out city with excellent roads and street art. It has grown from a bureaucrats’ town to a city for professionals in the infotech and education sectors, among others. Its urban economy now has apartment complexes which have taken over large tracts of the city’s surrounding agricultural land. Bhubaneswar is also an important sporting hub; World Cup hockey tournaments have been hosted here twice.

Photo: Pbedekar/ Creative Commons

Among the many questions that Bhubaneswar and its expansion raises is how villages are subsumed into it, mainly by urban land sharks who convert agricultural land into real estate opportunity. New speculative housing stock is created – but not for the poor and working people – the natural terrain is ignored, and piecemeal land filling is done which upsets the natural drainage of the region. Many hills and forests have been cleared or reduced in size too in the city’s expansion. It is an unsustainable development model – sadly, the planned city of Bhubaneswar which was meant to be the newly-independent India’s urbanism model has fallen prey to market forces that care little about public interest and sustainable ecology.

The city has expanded to 161 square kilometres and has more than 10 lakhs people. It is increasingly car-oriented, shows familiar traffic congestion issues and hardly any efficient public transport network. Roads are without pavements, safe cycling is an uphill task. Peak summer temperatures rise to over 50 degrees Celsius and Urban Heat Island effect is perceptible. Tree cover is diminishing, and frequent cyclones batter the city. The state government receives international recognition for its cyclone response measures preventing loss of lives, but sadly, it has no long-term measures to deal with Climate Change events.

Rampant construction activity and destruction of forests and coastal mangroves continue unabated. Two significant forests on either side of the city, Nandankanan and Khandagiri have been reduced in size. Khandagiri hill, once dreaded for its wildlife, has been split wide open by a freeway cutting across its centre. Across the hill, once impossible to reach, is Kalinga Nagar with large real estate projects. An important natural culvert in the city is being systematically encroached, including by government-approved entertainment parks and buildings, and could cause flooding during torrential rains. Such devastating climate events, besides loss of life and property, demand radically different vision for cities that is nature-led and not determined by free-market-growth.

Even within Koenigsberger’s plan, the implementation leaves much to desire but it is now imperative that city planning is both ecologically sustainable and socially sound. Every time I go to Bhubaneswar expecting the cool southern breeze, I am disappointed.

PK Das is an urban planner, architect and activist with more than four decades of experience. He has been working to establish a close relationship between his discipline, urban ecology and people through a participatory planning process. He was awarded, among other honours, the prestigious Jane Jacobs International Medal in 2016 for his work in revitalising open spaces in Mumbai, rehabilitating slums and initiating participatory planning process. He would like to place on record his appreciation for social scientist and author Ravi Kalia’s Bhubaneswar: From a Temple Town to a Capital City from which he has drawn for this essay.

Cover photo: Government of Odisha/ Creative Commons