As a nation, we in India woke up to the issue of high heat sometime in 2010-12 when a large number of deaths were reported. Following the deaths in Ahmedabad, the first city Heat Action Plan (HAP) was formulated in 2013. Then, other cities such as Bhubaneswar and Nagpur followed with theirs. In 2016, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) released guidelines to address heat waves after which they have been revised every year.

Progressively, more cities and states have been drawing up their HAPs and each city or state adds something when there are workshops in which best practices are discussed. When it comes to short-term measures against heat waves, there are examples where plans are working. For cities working on their HAPs, the template, from what I understand, is the Ahmedabad HAP because that was the first city plan prepared and implemented.

Currently, we at Visvesvaraya National Institute of Technology, Nagpur are developing a model HAP which can be deployed in various cities. We will submit it to the NDMA in April after the draft is reviewed by national and international experts. Once it is accepted, it can be taken to all cities which need a HAP. We have been working on it for the past two-three years, we reviewed 47-48 international HAPs, studied what was happening in Arizona, Sydney and Europe, and found out what the World Meteorological Organisation and World Health Organisation are doing.

The model HAP, which is scientifically worked out, has all the three components: Short-term, medium and long-term. But this is not a take-and-use plan. The model HAP will provide the much-needed framework with templates for studies and data-collection on how each city can make its HAP; it will address not only the immediate concerns but also the long-term changes needed to bring down the heat.

The idea is to have a strong data-based framework on the basis of which a city will draw up its HAP aligned with local factors. Our role is to ensure that framework is scientific and technical. Within this framework, each city will have to prepare its own plan based on its vulnerable population, where these people live, how much vegetation cover exists in the city and so on. It is not feasible for the nation or even a state to have a common HAP, each city should have its own which responds to local factors.

Photo: Biswarup Ganguly/ Wikimedia Commons

Ahmedabad model

The Ahmedabad HAP has been largely working and is regularly revised, but I want to emphasise that it addresses only short-term aspects which are important and needed, but an HAP should not stop at these. The plan should become a part of the larger development plan of the city. Despite some things working well such as bringing down heat-related deaths, long-term measures are yet to be designed or incorporated into the HAPs.

One of the most important components of a HAP is its adaptability because the measures that were adopted would have to be evaluated and their impact assessed before a revision can be made. Whatever measures were taken the previous year should be evaluated for their efficacy, and then the HAP appropriately revised.

That mechanism for proper evaluation does not exist which means there is not enough information of what measures worked in previous years and what needs to be changed. So, typically, either the same HAP is being repeated year after year, or officials pick up a few best practices and try to incorporate them in a plan. Systematic evaluation and revision are hardly done.

Beyond reducing mortality

The basic objective of a HAP is to save lives and reduce morbidity, but it is not the only one. Information and warning systems have played an important role since the NDMA guidelines in 2016 in reducing the number of heat-related deaths. Beyond mortality, on a long-term basis, there is the economic impact. The impact of heat waves on the informal sector or construction sites is yet to be studied properly. When people cannot work for a few hours every day, or the high heat brings down productivity, or people fall ill and spend money to recover while losing their wages, there is an economic impact.

The HAPs have largely been viewed as a public health issue but there are other domains too. The HAP should be ideally prepared at the intersection of public health, urban planning, economics, meteorology and so on. Heat is not a single domain issue. So, the framework should take into account multiple domains as well as the short, medium and long-term perspectives. The HAPs for rural areas must also include agriculture because in the long-term heat waves may affect food security too.

Work will have to be done on all aspects – from educating people and issuing warnings to providing relief measures in the short-term and seeing the link between heat waves and urban planning, transport options, energy management in the long-term. The purpose should be to build cities which become more heat-resilient and have the capacity to adapt. So, while mitigation measures are important, thought should be given to the way we plan our cities.

Everything is interconnected. The HAPs cannot be independent of all else. Large construction and use of building material which necessitates air conditioning means higher energy consumption which creates more anthropogenic heat and makes the city hotter. The more vehicles on a city’s roads, the more anthropogenic heat. Cities that are public transport-oriented and are bicycle and pedestrian-friendly, where urban planning measures are centred around existing ecology with importance given to green and blue infrastructure will see lower levels of heat.

Map: Magotra, R. Tygi, A. Shaw, M. and Raj, V (2021). “Review of Heat Action Plan’

Vulnerability mapping

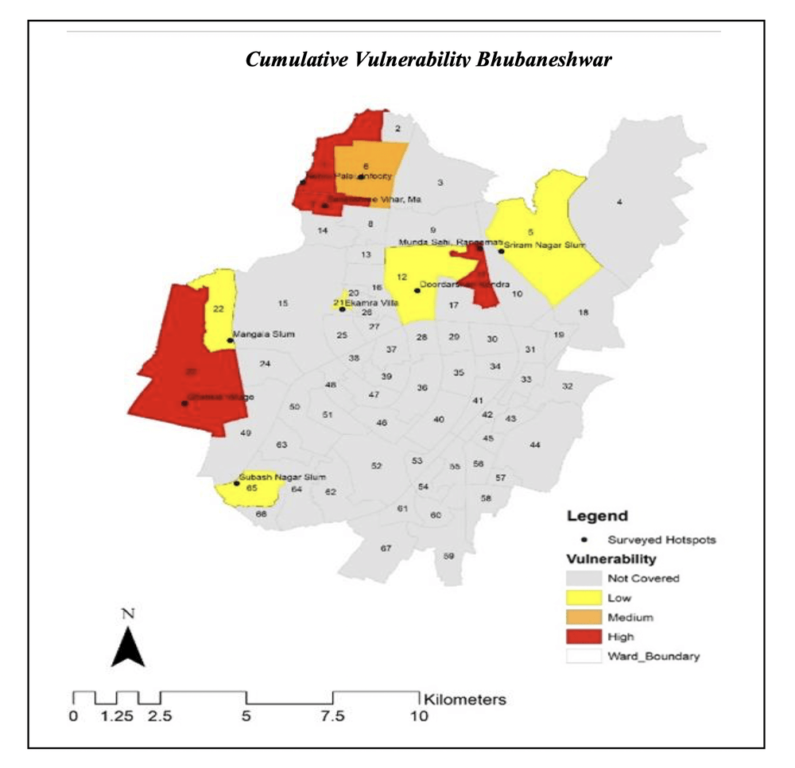

In an HAP, the short-term mandate is about the vulnerable people affected by heat waves – the socio-economically marginalised, the young, the elderly, and the outdoor workers. Local agencies are best placed to identify them in cities. But a plan should go beyond this.

In one of our studies in Nagpur, we did vulnerability mapping to find out which wards are more vulnerable, what adaptive capacity people have, and so on. A ward-wise heat vulnerability mapping can be best done by municipal agencies. Once this map is available, it can decide what to do to mitigate in the short-term and how to eventually reduce vulnerability.

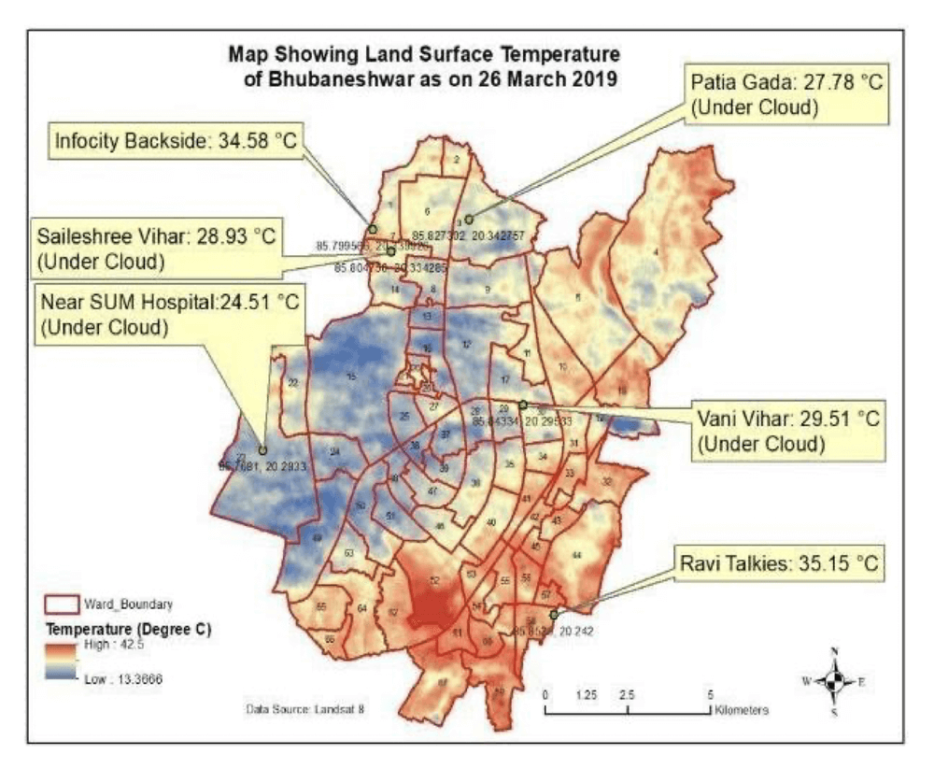

The local climate zone mapping is a classification system developed in Canada in 2012 to study the urban heat island patterns and has been used around the world to study heat stress. My team and I were perhaps the first to apply it to an Indian city, Nagpur. The basis is that a city does not have a single temperature; though the meteorological department says the temperature is 42 degrees Celsius, some areas in the city might record higher and experience a heat wave.

We also did a nocturnal heat island intensity study and found that certain parts of the city are very hot during the night while others are cooler; some are hot during the day but cooler at night. This variation and detail are available in vulnerability mapping, and are important for any city to formulate a good HAP.

Heat and city planning

In the last decade, the number of districts and cities experiencing heat waves has increased. Cities which were not in the hot region are also experiencing heat waves. The thresholds are also different – in a coastal area, it will be 37 degrees Celsius; in the plains like Nagpur, it may be around 45 degrees Celsius but hilly regions will see 30 degrees Celsius. Each city will have a heat wave when temperature rises a few degrees above the threshold, so it is not that cities in the hills do not need a HAP. Coastal cities like Mumbai and Chennai will also have to include relative humidity which increases heat stress. In fact, each city will have to study patterns and decide the threshold to declare a heat wave.

Historically, India is in a heat-prone region. It takes time to perceive heat as a risk here because we are used to high temperatures. Europe woke up early because heat is new to them. It is proven also that hot regions take time to accept that it is a risk. Even common people do not think it is a risk. Floods are a risk, so is heat, but because people can see floods, they perceive floods as high risk. People do not see heat, it is called a ‘silent killer’. So, HAPs are a relatively new phenomenon.

HAPs which consider all domains and aspects may be idealistic – I am called that too – but the truth is that solutions will have to be long-term, inter-connected, and will require policy changes. Economically too, it makes sense to have cities that are built around nature but the problem is that one has to say “economically too”. The Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC), which says that buildings should conserve energy, exists but has to be implemented in the spirit.

Heat is an urban planning issue too. Cities can reduce their heat to a great extent with critical urban planning – securing parks and playgrounds, having abundant tree cover, converting an average trip length of four-five kilometres into a walkable and bicycle-friendly stretch. If there is willingness at the topmost level, it can be done. Cities and their management are mostly governed by economics. When economics takes the front seat and the environment suffers, it creates such a crisis in cities.

Map: Magotra, R. Tygi, A. Shaw, M. and Raj, V (2021). “Review of Heat Action Plan’

Nagpur’s Local Climate Zones

The Urban Heat Island phenomenon gives us only two temperatures between a city and its outer areas; cities tend to be warmer than their surroundings due to a complex set of factors. However, there is no one temperature in a city; various areas fall in different temperature ranges. This intra-area difference also needs to be studied and responded to.

For a better and more accurate picture of the heat stress, a city’s local climate zones (LCZ) need to be mapped. Our team prepared a LCZ for Nagpur, the first city to be mapped this way. We shared our research with the Nagpur Municipal Corporation and assisted in mapping so that the Nagpur HAP, which we had helped prepare, is revised in a scientific way.

For the HAP to include long-term vision, that the city has to be understood well– we mapped the LCZs, studied the variations in temperature and heat stress, did vulnerability mapping followed by the outdoor thermal comfort studies. We are currently trying to map mortality against various meteorological parameters and studying morphological parameters. All these become the basis of revising the HAP.

Our studies are in the Nagpur HAP and, therefore, a guide for other cities. As scientists, we show how these studies are done; the data, method, and results are shared and provide the framework for any city to use. Our team is currently mapping LCZs in 15 Indian cities. We are also trying to automate some processes and develop our own machine learning techniques or tools in collaboration with computer scientist Dr. Ravindra Keskar because we cannot go to different cities. Data is critical – we had 17 loggers in Nagpur every summer from 2016 for about 70-80 days logging temperatures every 15 minutes, a vehicle with a sensor moving around collected data seven-eight times a day, the outdoor thermal comfort study was done for 16 days. Machine learning tools will help take these to other cities.

Photo: Piero Regnante/ Unsplash

Built environment and heat

The built environment in our cities contributes to the high heat. There are several approaches to tackling the heat stress. One is to improve the green cover and conserve the blue infrastructure. Then, the cool roof strategy used in Ahmedabad or roof gardens can be used in slums and low-rise buildings, though cool roofs wither and their impact reduces with time.

Another is to shift to cities where some areas are made conducive for walking or bicycles, and public transport is given primacy. Also, the city’s Development Control Regulations can be a combination of the built environment and vegetation cover, and can be modelled so that there is no substantial increase in the city’s temperature due to building activity. For example, real estate developers cannot fill lakes or chop hills to build housing complexes. This may take time but we should move towards it. Similarly with the transport sector, water availability, and so on.

Cities are not looking at heat and water with an integrated approach. If we start building cities around heat and water, many of our problems will be addressed; it makes economic sense too. Every time a city floods, it spends money and there are other economic losses. If you build around water, you take care of the water stress. If you build with sensitivity to heat, treating surfaces and using certain building materials, you take care of the heat stress. If you build with the green cover, it reduces heat stress and flooding.

The Vegetation Density Ratio, or the ratio of green to the total area, is an important factor in heat but the variation is more important. Nagpur, we can say, has so much percentage of green cover but it is not evenly distributed. The VDR varies in different areas and impacts heat, our study showed a higher VDR reduces nocturnal heat stress. In areas with low VDR, municipal agencies can focus on planting trees.

There are no quick fixes. We need both structural and non-structural approaches to tackle high heat. Cool roofs are a non-structural change, they do not impact anything fundamental. Structural change is when the way cities are planned and built moves away from the present paradigm. Our HAPs need to be a combination of both.

Dr Rajashree Kotharkar is professor at Department of Architecture and Planning, Visvesvaraya National Institute of Technology, Nagpur. She has done extensive research, published in peer-reviewed journals, on urban climate, mitigation measures for urban heat islands, and heat vulnerability mapping among others. She and her team recently submitted a draft model Heat Action Plan for Indian cities to the National Disaster Management Authority.

Cover photo: Ibrahim Rifath/ Unsplash