Pune, a city once renowned for its verdant hills, flowing rivers, and rich biodiversity, stands at a pivotal moment in its history – struggling to preserve its ecology. Nestled amidst the picturesque Sahyadri mountains, the city’s hills and rivers play a crucial role in regulating the local climate, maintaining biodiversity, and sustaining livelihoods. These not only provide scenic beauty but also support essential ecological functions.[1]

In 2017, the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) merged 11 villages and, in 2021, another 23 into city limits — turning fertile farmland into concrete jungles. Over the past decade, accelerating urbanisation has resulted in a staggering 300 percent increase in city areas. This threatens to irreversibly degrade the natural resources that have long defined Pune’s ecological and cultural identity. Their preservation has become the responsibility of grassroots movements, voluntary groups, and individuals committed to the cause.

As Ravindra Sinha, an environmental activist, explains, “The Green Pune Movement, an umbrella term under which most democratic green activities can be clubbed, is unique due to its comprehensive approach, integrating policy advocacy, environmental protection, and widespread citizen participation, creating a unique tapestry of activism to preserve ecology.”

On the policy front, leaders like Aneeta Gokhale Benninger, Sujit Patwardhan, Vijay Paranjpe, utilised their expertise in town planning and law in advocacy, supported by political figures like former Member of Parliament Vandana Chavan. “Groups in Baner, Pashan, Wagholi, and Vetal Tekdi engaged in tree plantations, watershed activities, and opposing environmentally detrimental projects. However, the movement’s core strength lies in people, with numerous concerned citizens and groups like the Panchavati Nagarik Samiti actively participating in democratic engagements, public events, and policy discussions to ensure that environmental decisions are based on scientific evidence and community consensus,” he says.

The multifaceted activism, with democratic participation, is a testament to what a city can achieve when its people join hands to protect natural heritage. Pune’s green movements are imperative for the ecological future of the city.

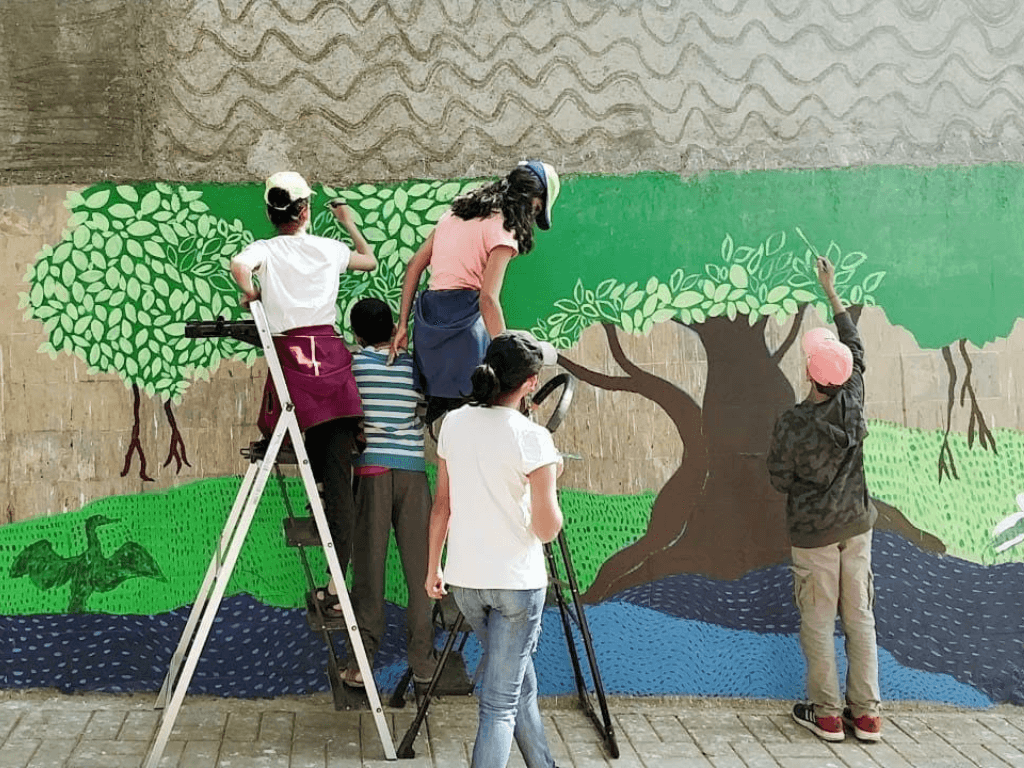

Photo: Meghna Baphna

Pioneering activism

“What Pune does today, Bombay does the following day and Delhi starts thinking about it a week later,” remarks Satish Khot, engineer and former president of National Society for Clean Cities (NSCC), Pune Chapter. The city was among the first in India to insist on waste segregation at source, despite facing significant resistance including criticism from major newspapers. Soon after the 74th Constitutional Amendment in 1992, the NSCC empowered citizens, through mohalla committees, to interact with municipal officers for their grievances. Its efforts made wet-and-dry garbage segregation a household term in the late 1980s and rallied against manual segregation.

Khot has supported movements to preserve open spaces, implement green development plans, and protect Pune’s rivers and hills. He emphasises the importance of sewage treatment to prevent river pollution and supports the anti-riverfront development movement. Khot remains committed to sustainable development, community involvement, and education about environmental conservation.

The Benningers’ crusades

Photo: Purnima Joshi

Aneeta Gokhale Benninger, a geographer-turned-town planner, co-founded the Centre for Development Studies and Activities (CDSA) with her architect husband, Christopher Benninger, in 1976. Over the years, she has championed for balance between development and the environment. Her activism journey began with the proposals to construct on Pune’s hills. Benninger and CDSA challenged the development plans that endangered the hills by mobilising citizens, engineering students, and local organisations through meetings, objections, and public talks.

Despite a planning committee stacked against them, the movement leveraged public pressure and legal channels to protect the hills. Her technical expertise and relentless advocacy led to the first definition and formal protection of the hills based on their gradient, preventing destabilising construction. Benninger then extended the fight to the rivers, arguing for clear legal definitions of riverbanks to protect them from detrimental development. Her pragmatic approach, grounded in geography and science, sought to protect natural resources while ensuring sustainable urban growth.

Lawrence Siddhartha Benninger, her son, is the director of the Institute for Sustainable Development at the CDSA. He initiated the Quantified Cities Movement and developed the iNagrik app to enhance citizen participation. The app enables residents to monitor their neighbourhoods, report issues like garbage, infrastructure, and noise, and upload observations. The app facilitates real-time issue reporting and collaboration between citizens and city officials. He says, “By identifying issues, citizens become caretakers, leading to behavioural changes and maturity.” A UNICEF-funded project enables him to engage school and college children as “guardians of the city”.

Reviving Pune’s Rivers

Shailaja Deshpande, founder-director of Jeevitnadi, embarked on the mission to revive Pune’s rivers after a transformative postgraduate diploma in Management of Natural Resources & Nature Conservation from the Ecological Society (ES). The movement began in 2014 when Deshpande and the ES alumni gathered for the first birthday of a friend’s son. They pledged to restore the river to a state where the child could play in it when he turned ten. This led to the formal establishment of Jeevitnadi in 2016.

The movement faced significant challenges initially, including mapping and documenting the severely encroached and altered river stretches. Deshpande and her team sought expertise from fields like archaeology, organic chemistry, and hydrology to develop a comprehensive restoration approach. Community engagement has been their cornerstone. Programmes like the Muthai River Walk, Mobile River Exhibition, and the Muthai River Festival were created to connect people with the river. The ‘Adopt a Stretch’ encouraged citizens to take responsibility for specific sections, leading to regular clean-ups and monitoring activities.

Jeevitnadi’s impact has been profound, inspiring citizens to adopt sustainable practices and work towards river revival. Its strong support to the anti-riverfront development (RFD) project has helped the latter. Says Deshpande, “Jeevitnadi requested authorities to change the scope of the RFD to a more scientific and holistic one. The river must be the priority. We helped create an ecological model for riverfronts which balances conservation and human use. In fact, in a first, an 800-metre restoration model DPR of Ramnadi we created will be implemented by the PMC.”

Photo: Purnima Joshi

Pune Bachav Mohim

In February 2022, protesters gathered at Vrudheshwar-Siddheshwar Ghat to commemorate one year of chain fasts to protect the Mula-Mutha rivers from the controversial RFD project. Environmental activists like Sarang Yadwadkar, Vivek Velankar, and Shailaja Deshpande voiced concerns about the project which involved creating embankments by reducing the width of the river and disrupting the ecosystem. They warned it would cause floods and disrupt city life. Yadwadkar exclaimed: “Our river is very ill, she needs intensive care in a hospital, instead she is being taken to a beauty parlour!”

Conceptualised in 2015-16, the project spans 44.4 kilometres — 22.2 kilometres along the Mula, 10.4 kilometres along the Mutha, and 11.8 kilometres along the confluence of both Mula-Mutha rivers. Three stretches along the Mula-Mutha are being developed. When Prime Minister Narendra Modi laid the foundation stone in March 2022, the activists approached the National Green Tribunal (NGT). On April 29, 2023, more than 2,000 staged a ‘Chalo Chipko’ demonstration to protest the felling of trees for the project. The PMC’s Rs 5,500-crore plan was to tame the river for recreational purposes.

Yadwadkar, architect and prime mover of the anti-RFD movement, pointed out that the claims of not disrupting the river flow were false and that it ignored the continued release of untreated water into the river. With rains and unprecedented flooding this monsoon, activists and others under the banner of Pune Bachav Mohim demanded that the project be halted. Despite the political backing for the project from the Bharatiya Janata Party and initial support from the Nationalist Congress Party, the project’s future is uncertain, thanks to the movement.

Yadwadkar, committed to the long fight, advocates preserving the natural beauty of the rivers: “Just let the river be…stop work and remove the debris dumped in the name of riverfront beautification.”

Parisar for sustainable urban transport

The journey began in the 1980s when Sujit Patwardhan, Vijay Paranjpe, and a few others concerned about Pune’s environment, came together to start Parisar, to advocate sustainable development and create environmental consciousness among people. Such advocacy was uncommon. They asked questions like “What can the city do to protect green spaces” and initiated lectures-discussions on water management and energy. Ranjit Gadgil, programme director, Parisar, says: “In a sense, Parisar set the stage for green movements in Pune and has been a catalyst for change, prioritising ecological sustainability.”

Parisar’s focus shifted to urban transport in 2003-05. The National Urban Transport Policy in 2006 and the Supreme Court’s orders on air pollution were pivotal. Patwardhan invited Enrique Peñalosa, the transformative Mayor of Bogotá, to Pune, to share his vision for sustainable cities. Parisar has since championed pedestrian policies, urban street design guidelines, a comprehensive bicycle plan, and bus-based public transport to reduce private cars and air pollution.

Guardians of groundwater

Ravindra Sinha is one of those quiet and gentle activists whose work focuses on the protection and conservation of vital groundwater resources. His Mission Groundwater initiative is a part of the Green Pune Movement. Its activities include protecting hills through native plantation, watershed protection, and catchment area treatment. Working closely with the PMC’s dedicated groundwater cell, the movement supports over 30 local resident bodies, including Anandvan, Green Hills Pune, and Vasundhara Abhiyan, and collaborates with organisations like Advanced Center for Water Resources Development and Management (ACWADAM) and Jeevitnadi to implement rainwater harvesting and groundwater recharge projects.

Despite the forest fires, illegal excavation, and pressures from the land mafia and builder’s lobby, the movement perseveres. Its impact is critical, particularly for Pune’s poor with 2.4 million living in slums and vulnerable to landslides, water shortages, and diseases. Sinha stresses the urgency of this work as the exploitation of natural resources continues, and warns that neglect will lead to severe consequences like floods and landslides. “We are fighting against time…eventually nature will win,” he says ominously.

Vetal Tekdi: Preserving Pune’s green lungs

For over four decades, Pune’s citizens have fought to preserve the Vetal Tekdi from the planned Balbharti-Paud Phata (BB-PP) Road. Initially proposed in 1982, it faced immediate resistance, resulting in its removal from the Development Plan. Despite this, the PMC persisted, driven presumably by developers’ interests. The 2.1 kilometre road, connecting Paud Road to Senapati Bapat Road, opens prime land for construction but at the cost of the hill’s ecology.

In 2006, activists Saili Palande and Parth Lawate, along with Vinod Jain and Maj Gen S.C.N. Jatar, secured a stay order from the Bombay High Court. However, the PMC included the road in its 2014 Draft Development Plan. An expert committee, including Jatar and Prashant Inamdar, then exposed the official claim that the road would alleviate traffic and showed its irreversible ecological damage. Last April, the Vetal Tekdi Bachav Kruti Samiti (VTBKS) protested the cutting of 2,000 trees with over 5,000 people joining the rally. As Sushma Date, active member of VTBKS, says: “The BB-PP road is not for people but for vested interests. We hear a builder has got approval for his township but we will continue.” The fight to save Vetal Tekdi is significant both for nature and people as they democratically demand transparency from authorities and stall the road.

Preserving an oasis for migrant birds

Photo: Mahesh Goudelar

“Geez, this is a green treasure right in the middle of the city,” Meghana Baphna’s heart leapt with joy when she discovered the Dr Salim Ali Biodiversity Park in Kalyani Nagar, after returning from the US in mid-2012. She was captivated by the beauty and rich birdlife in the park along the Mula-Mutha. The green space, originally suggested by noted ornithologist Dr Salim Ali and Prakash Gole, faced numerous challenges. Despite being a home for migratory birds — a bird count in 2017 showed over 1,000 of 112 species in one day – the park had trash, rubble, and waste from a nearby crematorium and a garbage transfer station.

Baphna, with like-minded individuals, worked with the PMC to clean the park and rechristen it as Dr Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary. Besides regular cleanliness drives, they did bird walks and educational workshops for students, and teamed with Jeevitnadi for sessions on river conservation. The park was threatened by road and metro constructions and tree cutting began without proper public hearings. This prompted Baphna and her group to organise a human chain of 800 people in December 2018.

Despite their appeals, the metro construction proceeded too close to the bird park. The volunteers then removed 90 tonnes of waste from the river’s islands but the park’s condition deteriorated. The RFD project further threatens the ecosystem of the birds but the local school and activists continue to clean the place in the hope that the park’s fate is not sealed.

Kalpavriksh: Enhancing green areas

In 1997, when environmental activism was vibrant, Kalpavriksh moved its head office from Delhi to Pune. The group, set up in 1979, was well known for its significant role in environmental advocacy and education. In Pune, it addressed local issues including tree-felling, published local field guides, and initiated campaigns like Safe Festivals. It also initiated Pune Tree Watch and Pune Citizens’ Environment Forum, collaborating with various groups to enhance green areas and environmental awareness.

Leading the volunteerism movement

Green movements in Pune have one thing in common – the omnipresence of volunteer Sathya Natarajan. A passionate environmental advocate with many accolades, Natarajan is known for his exceptional ability to connect various green movements across the city. Working night shifts at an IT company, Natarajan dedicates his days to volunteering to nurture a vibrant network that inspires citizens from all walks of life to take environmental action. His leadership has not only united diverse initiatives but has also transformed volunteering into a powerful movement, driving collective efforts to preserve Pune’s natural heritage and promote sustainable urban growth. “I have volunteered with over 60 NGOs and community groups, some of which I have conducted, and done 10,000 such journeys over more than 15 years. I engaged with 1.25 lakh volunteers for the Adar Poonawalla Clean City Initiative,” he said.

The future of Pune hangs in balance

These and other green movements have been battling against the rapid deterioration in the city’s natural resources as urbanisation steamrolls. People, driven by their passion and commitment, have taken significant steps to protect Pune’s ecological wealth. While this demonstrates the power of community action, the need for sustainable urban planning – or nature-based planning – cannot be overstated.

The future of Pune’s natural wealth hinges not only on policymakers and planners, but equally on people working together to ensure that development does not come at an unsustainable environmental cost. The green movements offer a blueprint of community-driven initiatives leading to meaningful changes. Mahatma Gandhi once said, “The earth, the air, the land, and the water are not an inheritance from our forefathers but on loan from our children.” Pune’s green warriors have been vigilant guardians of this loaned ecology.

Purnima Joshi Founder Trustee of Team Swachh Kalyani Nagar, a volunteer citizens’ group turned NGO that has won the PMC Swachhata Award three years in a row and built Pune’s first Resource Recycling Centre. She also co-founded Swap, a hyperlocal platform for exchanging pre-owned items, now active in 15 cities. Currently, she serves as Communications Coordinator at Climate Action Network South Asia.

Cover photo and wall painting: Abha Bhagwat