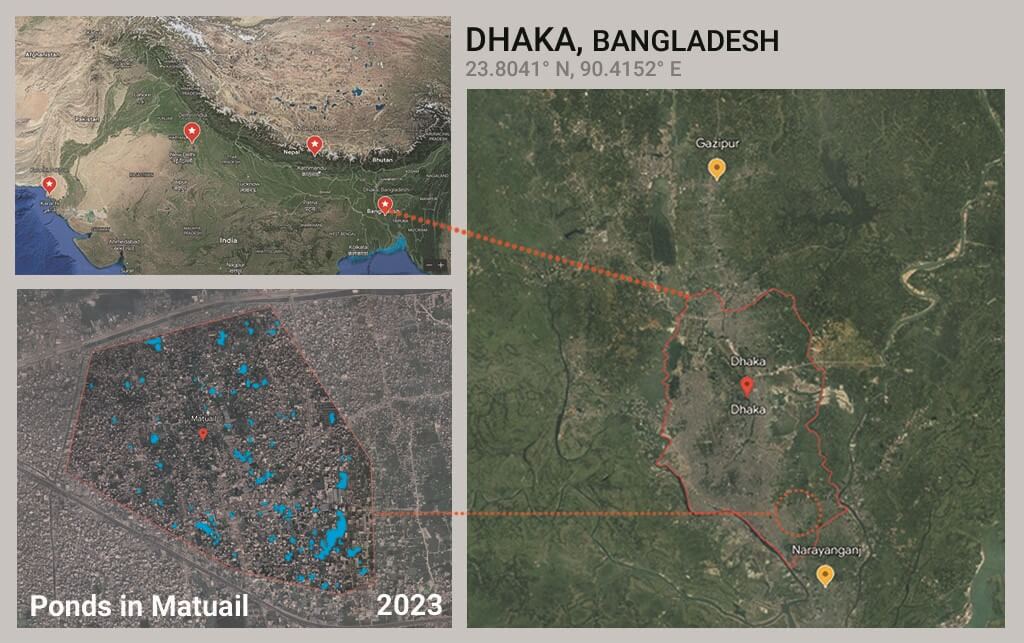

Matuail area lies at the southern end of Dhaka, capital city of Bangladesh, presents a study in contrast. One side of the Hazi Badsha Miah Road in Matuail has industrial sheds while the other sports high-rise residential buildings. What appears ‘development’ from a distance unravels into haphazardness at a closer look. Without a functional drainage network, Matuail has prolonged waterlogging – sometimes even without rainfall. People here have learned to live with the predicament.

Amidst the giant concrete buildings is a patch of land, sunk into the earth and perennially waterlogged. Originally a paddy field, it now resembles a pond with standing water through the year. On this 0.14-acre land, 60-year-old Mozaffer Hossain lives with his family in a tin-shed. As neighbouring plot owners elevated the base of their buildings, and the Road Transport and Highways Department raised the road, Hossain’s land subsided. “Every monsoon, rainwater gets deposited here and remains stagnant through the year,” he said.

Map: Shivani Dave

A resident of Matuail for the past 25 years, Hossain used to cultivate paddy on the surrounding croplands with an output of a hundred maunds of rice every year for the land owners. He recalled that, even a decade ago, this was a vast green field and scattered wetlands which were converted into high-rise buildings. “Nobody gave importance to developing the drainage,” Hossain rued. After rainfall in mid-July and mid-August, the water was stagnant for days later. His wife, Zamina Khatun, regretted that they could leave the land taken from the landlord but found it difficult to live without basic necessities – including, ironically, drinking water.

In fact, most of Hazi Badsha Miah Road had knee-deep water at various places days after rainfall this monsoon. Hossain’s story is one of the many in this part of Dhaka where ‘development’ has come to hold different meanings for people based on their station in life. When the water finally subsides, they have to brace for searing rising heat. In Dhaka – the greater metropolitan area with 22.4 million people with one of the highest density urban agglomerations in the world – both rainfall and heat have exacerbated in the times of Climate Change, multiplying the challenges for poorer and marginalised families like Hossain’s.

Photo: Noor-A-Alam

Higher incidences ahead

“Normal distribution function was adopted to forecast rainfall variability due to global climate change and found that annual daily maximum rainfall equal or greater than 200 mm might occur in any 12 years during the period of 2010 to 2066…Any drainage structure to be designed and constructed in Dhaka should be resilient to extreme rainfall events. The existing system was designed based on historical rainfall data, but the capacity of the drainage network will not be sufficient enough,” observed this decade-old study by scholars in Australia.[1]

Studies have demonstrated that the situation is likely to worsen in the years to come, both of rainfall and heat. Greater Dhaka has been experiencing longer summers with heatwaves followed by weaker monsoons and shorter winters. This April 15, Dhaka recorded the highest maximum temperature in decades at 40.6 degrees Celsius and June saw high heat too leading to closure of schools. There could be “an increase in the likelihood of such an event to occur of at least a factor of 30 over India and Bangladesh due to human-induced Climate Change…the likelihood of this April’s event recurring would increase by about a factor of 3 between today and reaching 2 degrees Celsius global warming, meaning that this humid heat event could be expected every 1-2 years,” warned a study by World Weather Attribution[2]

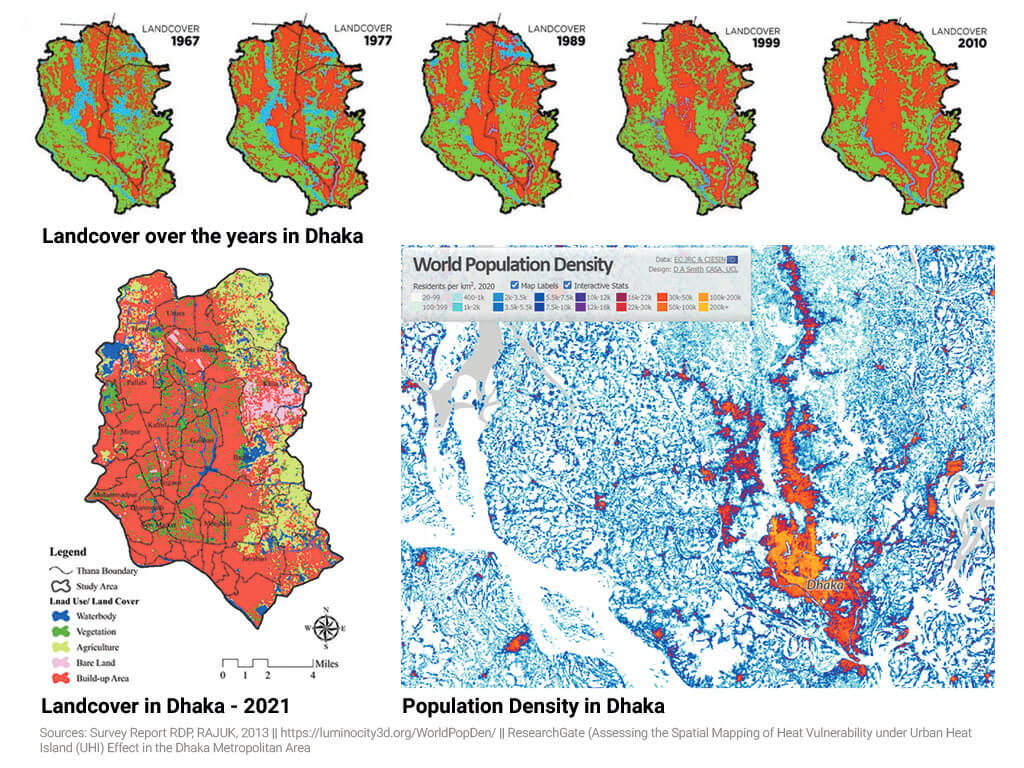

The Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) estimates that the frequency and duration of heatwaves in Dhaka have increased over the last 30 years; the city now has more built-up areas than natural vegetation and wetlands. An analysis of BMD records between 1989 and 2023 suggests that the frequency and duration of heatwaves over Dhaka are rising, especially since 2014 which was the hottest year so far. BMD meteorologist Dr Muhammad Abul Kalam Mollik told Question of Cities that the trend of five-day-long mild-to-severe heatwaves is increasing.

As Zamina Khatun narrated, the extreme weather situations mean mosquito menace and a weird combination of “hot-wet air” or high humidity which “wraps us most of the time”. Like Hossain’s family, thousands of underprivileged families are trapped in uncomfortable and unhealthy lives not only in Dhaka but also in Narayanganj and Gazipur. Narayanganj, approximately 26 kilometres from Dhaka at the confluence of Sitalakhya and Dhaleswari rivers, is a market for jute and hides, and forms part of the industrial region of Dhaka. Gazipur, also located 25 kilometres from the capital city, is a textile hub.

A study shows that more than 50 percent of manufacturing industrial employment is concentrated in the Dhaka-Narayanganj-Gazipur zone.[3] This has meant large-scale urbanisation undertaken rapidly, without adequate planning, to support the rural-urban migration. The population densities[4], especially in Dhaka, are worrying: 39,353 people live per square kilometre in Dhaka South City while the population density in Dhaka North City and Narayanganj are 30,474 and 13,361 respectively.

Photo: Noor-A-Alam

In Narayanganj, a narrow alley named Khankar Goli linked to Pakka Road gets inundated with 30 minutes of heavy rain despite being close to a pond. The hyacinth-covered pond, a private property, is surrounded by residential buildings on all sides and has become a dump for municipal waste. Till 20 years ago, it was connected to Sitalakkhya River, 800 metres to its east, and had ferry services. “Even a decade back, with a few buildings scattered across the vast wetlands, rainwater would recede fast. The alley was developed on a box culvert. It’s clogged now, the pond has lost the capacity to carry excess rainwater,” said Habiba Begum, 48-year-old mother of three who assists her ailing husband Marfat Ali to run a small grocery shop near the pond. The rusty floor of their shop shows the impact of flooding. They prefer the shop to their home because their tin-shed house amidst the congested buildings becomes a heat chamber.

Multiple authorities

The impact of extreme heat or rain has been crippling on most people. When those affected approach city authorities, they are advised to elevate their house basements at their own cost, as the Narayanganj City Corporation Mayor did when residents complained about waterlogging in Khankar Goli. The authorities deal with waterlogging by unclogging the drainage network – occasionally – but private land development is not a civic issue.

The multiplicity of authorities does not help. The Hazi Badsha Miah Road, for example, was constructed by the state-run Roads and Highway Department; the area has been under the Dhaka South City Corporation since June 2017 but it cannot address waterlogging or construct a drainage network because the Road has not been handed over yet. Neither the Corporation nor Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha RAJUK (Capital Development Authority) can deal with issues of private land development. The better-off land owners and realtors freely landfill – with no consideration for neighbours.

The absence of a single authority has meant lack of coordination, which has had an impact on planning – or the lack of it. Usually, land price is fixed based on location, road connectivity, access to hospitals, markets and educational institutions. However, land prices remain constant in Matuail because the land has to be developed after purchase to address the water-logging.

Compromised planning

The cities did not reach this point due to lack of planning. In fact, the greater Dhaka area plans date back to 1917 when the renowned Scottish town planner Sir Patrick Geddes prepared “Report on Town Planning, Dacca” in which he highlighted the need to protect water bodies and green spaces. Within nine years of the formation of Pakistan, the Dacca Improvement Trust (DIT) was set up; in 1959, the capital of the then East Pakistan had its first Master Plan which showed 38 percent water bodies and 5.1 percent open spaces. In 1987, the DIT transformed into RAJUK marking the shift from ‘improvement’ to ‘development’.

In 1995, it adopted the Dhaka Metropolitan Development Plan covering 1,528 square kilometres of Dhaka, Gazipur, Narayanganj cities and outskirts, and included three time-specific Detailed Area Plans. The DAP 2010-2015 marked 27.27 percent of the total land as agricultural zone, 24.70 percent as flood flow zone, leaving 0.94 percent for open spaces and 9.52 percent for water bodies. Environmental degradation was written into the plans, so to speak.

Between 1989 and 2020, Dhaka city lost 56 percent of its vegetation even as its urban cover increased to 82 percent, found a study[5] two years ago. A study on Narayanganj observed that between 2011 and 2019, vegetation and agricultural lands reduced by 21 percent.[6] In Gazipur, a study estimated that agricultural land which accounted for 63.44 percent of the total land in 1999 was barely 22.10 percent in 2019.[7] The Bangladesh Institute of Planners (BIP) study revealed that areas under plans had lost at least 22,516 acres or 22 percent of the total wetlands till 2019 in the name of land ‘development’.[8]

Photo: Noor-A-Alam

Independent urban planners blame successive governments for undermining the DAP. Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) reported in January 2020 that the DAP was revised 158 times between 2010 and 2018 on instructions of the ‘high-powered cabinet committee’, including for filling up water bodies.[9] Professor Amanat Ullah Khan, retired faculty in Geography and Environment Department, University of Dhaka, was a spatial expert in the formulation of DAP 2010-2015 but he soon resigned. “The area lost its green and blue spaces because the government didn’t want to conserve them,” he told Question of Cities, “Making cities livable is a political decision.”

The rapid urbanisation of Aauch Para, in Tongi Municipality, Gazipur, underscores this. When Abid Iqbal’s family bought land for family home in 1993, they motivated other landowners to sacrifice small land parcels for a 2.5-kilometre mud road to connect to Dhaka-Mymensingh highway; this was soon turned into a brick road by the Municipality which dramatically increased the price of the low-lying lands. It showed how unplanned ‘development’ can be.

The National Housing Policy 2016 excludes flood flow zones and agricultural land from residential projects, besides restricting development on river, canal and lake. The Private Residential Land Development Rule 2004[10] prohibits narrowing wetlands and natural drainage channels for land development and, according to the Open Space Act 2000[11], natural water bodies marked in a Master Plan cannot be used for such purposes. Then, how landowners converted agricultural lands or flood flow zones into congested built areas, is a question that authorities have to answer.

Matuail represents this. It lies in the 56.79 square kilometre Dhaka-Narayanganj-Demra (DND) irrigation project area which protected the floodplains of Balu, Sitalakkya, and Buriganga rivers. Rice was produced on more than 14,000 acres here till 1970. When the devastating flood of 1988 inundated most of Dhaka, people believed that DND area was safer, leading to the conversion of floodplains into urban areas; soon, Matuail was part of Dhaka South City Corporation.

“The construction of buildings aggressively encroached canals; land developers and building owners did not leave space for even a sewage channel,” said Shamsuddin Bhuiyan, Matuail’s ward councillor. According to the minutes of an inter-ministerial meeting in 2020, as many as 22 educational institutions, 22 religious centres, utilities, and public and private offices were identified as encroachers on the drainage network. Where will the water flow?

Climate Change, a global phenomenon, has severe local impact when anthropogenic factors combine with it. The 2021 study[12] in the Journal of Geographic Information found that land surface temperature in Dhaka Metropolitan area increased by 2.48 degrees Celsius in March and by 3.76 degrees Celsius in May this year. Narayanganj and Gazipur too witnessed a rise in temperature[13] where heavy industrialisation and urbanisation occurred recently. Urban planner and ICLEI’s Bangladesh representative Jubaer Rashid stated that none of these cities were ‘climate resilient’ adding, “Science-based interventions are important, but political will and citizens’ participation are necessary to save cities from climatic hazards.”

Photo: Noor-A-Alam

What lies ahead

In the new DAP 2022-2035, RAJUK proposed 28 percent of agricultural land, 7 percent for water bodies, 1.55 percent open space and 1.41 percent urban forest of the Greater Dhaka area. In ecological terms, this is hardly an improvement over previous plans and offers little to address Climate Change. However, it proposes five regional parks of minimum 100 acres each and 49 water parks to accelerate groundwater recharge, and discourages housing projects on small plots to increase collective land for water to soak.

With an astounding 80 percent of the country’s population is projected to live in urban areas by 2050, according to Md Ashraful Islam, RAJUK’s Town Planner, it would lead to severe pressure on existing vegetation and wetlands. “Vested interest groups are trying to manipulate the new DAP,” he disclosed. Green campaigners believe that the new plan has many loopholes such as the non-marking of flood flow areas which will allow RAJUK to give conditional land development approvals. “It will allow new towns by converting the already depleting wetlands,” said Syeda Rizwana Hasan, Chief Executive of Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association.

The new DAP, however, encourages block model development in which multiple land owners collectively build a single large multi-storey building and leave 40 percent of the land as open green space. On paper, this looks impressive “but it does not specify the minimum range of a block or make it mandatory,” remarked Professor Adil Mohammed Khan, faculty of Urban and Regional Planning department at Jahangirnagar University. He recommended policy instructions so that landowners cannot elevate the baseline of their land and road authorities do not elevate roads at whim.

Such glaring gaps persist in planning even after the impact of Climate Change has been well recorded. As Dhaka, Narayanganj and Gazipur gallop towards greater urbanisation and densification, sound ecological-based planning is urgently called for. Instead, might is right which means more instances of Hazi Badsha Miah Road might be repeated and millions like Mozzafer Hossain will still be left at the mercy of extreme weather events.

Sadiqur Rahman, a post-graduate of the University of Dhaka, is currently employed as a journalist in The Business Standard. His 10-plus-year career in journalism includes reporting on Climate Change, biodiversity conservation, local business, and livelihood-related issues. A member of the Thomson Reuters Foundation Alumni Club, Bangladesh, he won two anti-corruption media awards in 2014.

This is the first part of a series supported by the QoC-CANSA Fellowship to report on Climate Change and cities in four nations of South Asia.

Cover photo: A waterlogged road in Board Bazar area in Gazipur by Noor-A-Alam