When Mumbai’s suburbs drowned in never-before rainfall and floods 20 years ago on July 26, the city re-discovered the Mithi River, its pivotal role as a storm water drain, its compromised carrying capacity, and its reduced status as a nullah for the city’s waste. Mumbai’s skewed and unsustainable relationship with the Mithi – and other rivers like Dahisar, Poisar and Oshiwara – was laid bare.

In the two decades that passed, a host of studies and review reports were done on the Mithi, action committees were formed, the Mithi River Project was launched, a Supreme Court-appointed committee of experts did periodic checks, and nearly Rs 3,545 crore (Rs 1,160 crore spent and Rs 2,395 crore worth tenders issued)[1][2] have been allocated. Yet, today, the Mithi flows filthy, stinking, and, importantly, massively walled in and disconnected from Mumbai’s daily life. It is remembered by Mumbaikars and the city’s administration only on days of intense rainfall, wondering if it will efficiently drain the rain.

The Mithi should be, ideally, more than a storm water drain. This purely utilitarian approach is limited and unsustainable, but even this has not been fully addressed. On the contrary, in the past few years, the very idea of Mithi as a river has been contested both in the corridors of power and in public policy analysis.[3] What could be more disastrous and myopic than, for a city built on water, to question the existence and nature of its longest river?

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

The exploitative utilitarian approach is, partly, what led to the Mithi swelling and behaving furiously on July 26, 2005, inundating slum colonies and industrial units on its banks and leading to many deaths. Partly, it was the unprecedented 944mm of rain in only a few hours that did Mumbai’s suburbs in. A total of nearly 1,100 perished that day.[4] Though Mumbai largely forgets the Mithi, those who live or work by it cannot. Like Sujata Suresh Kakwal, 60, a resident of Samartha Chawl in Kurla, who told us: “We lost everything then, we are very scared. Now, in heavy rain, we just prepare for the worst.” Here, people have raised the plinths of their houses up to 1.5 metres above the ground.

Haseena Khatun, a resident of Bamandaya Pada, Andheri East, who played in a placid Mithi in her childhood, recalls that day with dread: “26 July me kafi log beh gaye, samaan beh gaya tha. Bohot nuksaan hua (On July 26, many people were swept away, belongings were swept away. We had immense losses.)” Thousands like her who live in slums and work in small units by the Mithi, also treat the river as a receptacle for their waste. Two decades of clean-up efforts and concrete walls cut off the river from the slum dwellers but have done little to bring the Mithi back to life.

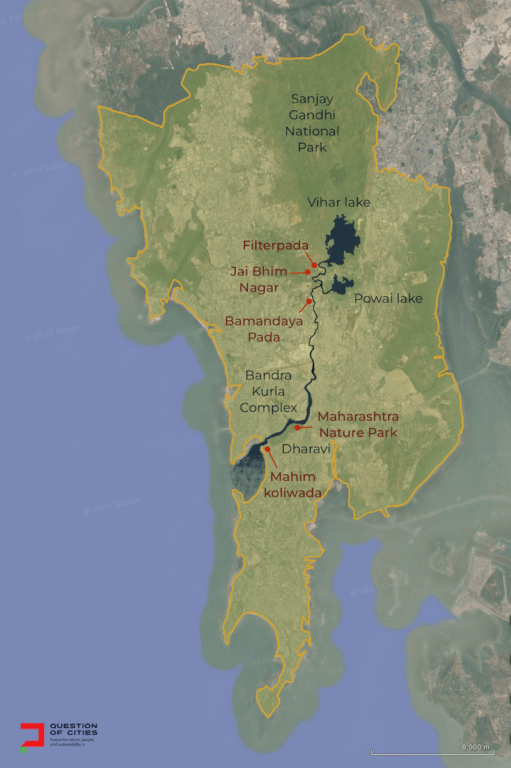

From its origin in the outflow of the Vihar Lake in the hills of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, the Mithi flows 17.84 kilometres of Mumbai’s terrain[5] before meeting the mangroves at Mahim-Bandra and emptying into the Arabian Sea. On this course, the Mithi is not one river; it has many avatars and each calls for a different kind of attention. Are Mumbai’s agencies in charge of the river – Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, MMRDA, Mithi River Development and Protection Authority – sensitive to this? Do they imagine a restored and reinvigorated, ecologically sustainable, river?

Map: Nikeita Saraf

Many Mithis

The waters of the Mithi flowed across the terrain before Bombay was constructed by the imagination and engineering of the British. The river predates the urban landscape. But the creation and construction of Bombay, by landfilling and reshaping its map, meant that the lines between water and land were altered and transformed to create land. This stemmed, as authors Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha noted in their seminal work SOAK, from the belief that “land and water are separable”. This was the first intervention.[6]

The Mithi of the British era was not the seasonal river of 1950-60s as Bombay embarked on development projects; it was bent to accommodate infrastructure projects. This Mithi, which still swelled every monsoon and retracted later, was not what Mumbai encountered on July 26, 2005, because the areas it flowed past were more densely constructed, its waters deeply polluted, and floodplains and ecology broken.

The post-flood work could have focused on repair-rejuvenation of the land-river ecology. Instead, the focus was merely on flood control and walling it, including near its source which prevents water from streams and other sources feeding it. Though the embankment walls have given some respite from flooding in a few areas, they have largely cut people off from the river – rather divorced the river and its ecosystem from Mumbai. The impervious walls might have slightly helped restrain the rising water but they were not, as the SC-appointed committee pointed, the ecological or sustainable way forward.

Twenty years later, the Mithi still struggles to flow. Its water is still almost black, has floating waste including discarded plastic bottles and carry bags, and emanates a putrid stench. The BMC’s pumps to flush out water from low-lying areas but people in slums have made their own arrangements too by putting up three-feet high boundary walls. The river widening has also displaced people.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

The Mithi riverwalk

Despite the work of the 17.3 kilometres of retaining walls and desilting worth Rs 1,150 crore over 20 years, the Mithi is not a river one to stroll by.[7] On this walkthrough, it was never difficult for us to find the river – we just had to follow the stench.

- Filterpada

Filterpada is the first settlement on its course. Here, the Mithi has Hydrangea and filth along its walls. Some men fish, others cross the barely-flowing river to play cricket on the lawns opposite. Most residents say that they have no relationship with the river but flooding has reduced in the three years since the walls were built. Chinta, in her 40s and living here since 20 years, lost a part of her house to the river widening work. Ishrat and daughter Zeenat, 32, recount how the river flooded in 2021 too. “Main so rahi thi jab ghar mein paani aaya, uthi toh paani mein tair rahi thi. Palang se lekar bistar, sab sadd gaya. (I was asleep and remember waking up floating in water. The bed and bedding were soaked rotten).”

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

- Jai Bhim Nagar

By the time, the Mithi reaches here, it has inched its way under Aarey Road. From the stairs of the pipeline here, one can see discarded suitcases, mattresses, and plastic carried by the Mithi. We spotted children throwing rocks into the river. Here, BMC’s sewer cleaners Govind and Chotelal spend eight hours most days removing sludge from drains. Reddy, a bus driver whose house used to be repeatedly flooded, told us: “This area stopped flooding after walls were built two years ago. Before the IT office buildings came up, we used to swim in the river.”

- Bamandaya Pada and Saki Naka

At Bamandaya Pada, the Mithi shows effluents from factories. Near the Military Road Bridge, the BMC’s annual nullah safai is in progress. A JCB excavator lifts black sludge and dumps it into a truck as dirty water drips to the road. The houses, many 90 years old, were demolished to widen the river; an embankment wall and a road sit on the riverbank. The entrances to people’s homes lie a few feet below the road but, as elsewhere along the Mithi, people have not been fully rehabilitated.

Chennamma, in her 50s, whose house was demolished, told us that most got compensatory housing in resettlement colonies in Mahul but returned. Mahul, as the Bombay High Court pointed out in another case,[8] is unfit for human habitation. At Saki Naka Creek Bridge, you can never be sure if the river is flowing. The footpath has waste strewn all over and discarded plastic bottles are below the bridge. Along the river are several delivery kitchens and small restaurants. On the other side, we saw effluents being discharged. The Mithi chokes.

Photo: Moina Rohira

- Dharavi

The Mithi’s network has several nullahs flowing into it. The new Dharavi Metro station lies along one of them; another, the Dharavi nullah, meets the Mithi at the famous T-junction. People and traffic stop here to throw trash to be carried to the sea or relieve themselves. Dharavi and the Mithi are neighbours – for years ignored by the city, now in the eye of redevelopment. On the Sion-Bandra Link Road here, Munna, 35, runs a nursery. From his makeshift hut of four years, he says the nullah does not flood but rises in the monsoon while the stench and trash are always around.

- Maharashtra Nature Park

At the Mithi’s confluence with the mangroves at Mahim, lies the Maharashtra Nature Park (MNP). The mangroves act as a porous barrier between the river and the sea, and help prevent floods. But the BMC built 17.3 kilometres of the proposed embankment wall along the Mithi’s edges, cutting it off. The fencing of the MNP has further cut the river off from popular sight – and imagination.

From here, the 620-acre intrusion of the Mithi river basin, the posh Bandra Kurla Complex, rises tall. The expensive office-residential-leisure quarter is hardly spoken of as “encroachment” though it was sited over the Mithi’s floodplains.[9] From these high rises of India’s costliest commercial district, the Mithi is the ugly face of Mumbai.[10]

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

- Mahim Koliwada

At Mahim Koliwada, where the Mithi meets the Arabian sea, the beach has nothing but trash. The residents of Mahim Koliwada want nothing to do with the river. Many of them have moved here recently from the demolished informal settlements around Bandra station. They showed us where water breached walls when it flooded. Student volunteers clean here on weekends but Idris Ansari, 35, a shopkeeper says, “The cleaning efforts have not made a difference.”

The disconnect between Mithi and Mumbai

Despite voices of reason and study reports advocating better integration of the river with the city’s planning, the past 20 years have seen construction around the river and its segregation from people’s life. The approach has been to tame the river to prevent a 2005-like flood. One of the recommendations of the Madhav Chitale Committee, set up after the July 2005 floods, was to de-clog Mumbai’s rivers and natural streams, and clear encroachments to improve the flow in all the rivers – which has been largely ignored.

In 2018, the SC’s expert committee suggested complete rehabilitation of slums and other settlements to maintain a 50-metre No-Development Zone along Mithi’s length – to give water its space to rise and ebb. Our riverwalk showed that this has not happened. In 2019, the expert committee pointed out the landfilling for roads and flyovers at Mahim Bay had encroached into the river. This, along with the expansion of BKC on the Mithi’s basin and floodplains, choked the river and narrowed its mouth causing polluted water to flow back into the city when high tides coincide with heavy rainfall. Who will address this?

Restricting the river and constructing on its floodplains means the river ecology has been forgotten. The argument that the Mithi is not a real river opens the floodgates to treat it as a developable resource for a city that puts the highest premium on land – at the cost of its natural areas. How will the Mithi service Mumbai’s storm water drainage? In 2019, the BMC and MMRDA claimed that the conveyance capacity of the river basin had increased by three times and that of the river by two times, but the SC-appointed committee quashed the claim.[11]

Despite the crores spent on concrete walls, sewage treatment plants, and desilting,[12] the Mithi is choked. This March, the BMC issued a desilting contract worth Rs 468 crore for the city’s drains and the Mithi.[13] The recurring expenditure was made necessary by the wall-building approach to flood management rather than an ecology-based approach which might have not led to so much silt.

Today, Mumbai and Mithi remain as disconnected as they were 20 years ago.

River ecology

The disconnection, the limited imagination of Mithi in terms of flood management, means the river’s ecology has been largely forgotten. Downstream, the Maharashtra Nature Park has nearly 300 varieties of plants, 115 species of birds, and several insects while the Mahim Bay is a sanctuary for migratory birds[14] in 2009, it was reported that shrimps, prawns, crabs, seagulls and migratory birds like black-winged stilts and godwits were spotted in the river’s vicinity.[15]

Without recognising and renewing the Mithi’s ecology – and that of all the rivers and water bodies in Mumbai – flood management will remain piecemeal engineering efforts.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Essentially, what lies at the heart is Mumbai’s relationship between water and land. By restricting rivers and constructing on floodplains, what has been normalised is that we humans can determine how much space the rivers can have. When it rains heavily and the rivers need to swell to fill its floodplains, there’s no space. Where should the waters go if not inundate our concretised streets and buildings?

It is not ecologically sustainable to address a river only through the flood management perspective. The Mithi is not merely a stormwater drain but a part of a complex network of wetlands, creeks, nullahs and wells across Mumbai. To divorce it from this complex web is ecologically unwise. Although the Chitale Committee Report devoted a chapter to the environmental aspects of Mumbai’s rivers, it also recommended landfilling and opening up salt pan lands – a licence for the authorities to merrily build more around the Mithi and other natural areas.

For Mumbai’s authorities to believe, as climate change impacts become frequent and intense, that the city can be sustainable without restoring its rivers and waterbodies – especially the Mithi –is itself unsustainable.

Smruti Koppikar is a Mumbai-based award-winning journalist, urban chronicler, and media educator. She has more than three decades experience in newsrooms in writing and editing capacities, she focussed on urban issues in the last decade while documenting cities in transition with Mumbai as her focus. She was a member of the group which worked to include gender in Mumbai’s Development Plan 2034 and is the Founder Editor of Question of Cities.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Cover photo: Jashvitha Dhagey