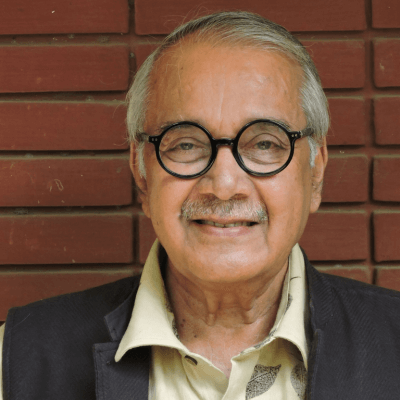

Prof KT Ravindran is uniquely placed to reflect on how urban design reflects in the city, why planning falls short given that it produces ‘mechanistic’ cities, and how ignoring water flows and landform relates to the environmental crisis exacerbating climate change. He works in the public decision-making sphere, addressing the environmental sustainability of national-scale development projects and advocates involving local people in redesigning their space.

Prof Ravindran, the Founder President of the Institute of Urban Designers, was also Dean at the RICS School of Built Environment, Professor and Head of Urban Design at the School of Planning and Architecture in New Delhi. He has served on government committees, including the one to build a new capital for Andhra Pradesh, and several national and international juries. He has been an advisory board member of the United Nations Capital Master Plan in New York, chairperson of the Delhi Urban Art Commission, and a trustee of the Indian Heritage Cities Network Foundation besides being associated with INTACH from its inception. He was most recently a Lead Member of the Kerala Urban Policy Commission, the only one of its kind in India, to chart urbanisation of the state for the next 25 years.

Photo: The Kerala Museum

What is urban design and why is it important?

It is not an easily definable subject or just some sort of aesthetic or objectification of the city. Urban design is about imagining the city in the third dimension along with its people who bring up the fourth dimension, imagining it as a crucible of activity with the people in it. It has to lead to a better lived experience for people.

Urban design has been dominated by a two-dimensional imagination of the authorities when they follow the path of town planning as the only instrument to intervene in the city. It’s the conventional understanding but not enough. Town planning is very good at defining what should not be done but it’s not very good at defining what needs to be done. As a result, our cities don’t have any affirmative action in them. For instance, when you say land use, it’s more about limiting kinds of uses than looking at the dimensions of a specific use for which it is proposed. Then, you have to move to the next level of typology because a school and a hospital cannot function from the same typological building.

What would be examples of good urban design in India, in any city, that you’ve come across or worked on?

What is good urban design changes from situation to situation. For instance, if I take the old city of Delhi, I would say it has a very strong urban design structure. It has the Red Fort and the Fatehpuri Masjid right across, connected by Chandni Chowk; another element, the Jama Masjid is linked to the Red Fort in a different way. You have different gates, different bazaars, and activities, all interlinked by different hierarchies of roles. And that provides an unassailable structure to the old city so that even when the population expands from 1,50,000 to 5,00,000, it still remains a strong structure. This is because the basic structure of all the components and their relationships was firmly established using the landform.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What are the ways by which such relationships get established?

The fundamental basis is human activity – not use, but activity. Structure will follow activity. Landform is also a very critical element. I think a primary manner that town planning has failed Indian cities is because it ignored landform as an element of good design. For instance, every Indian city floods because the authorities never considered the land profile as a criterion for design or planning it. The advantages that one would traditionally get by having locations in higher areas, and the individual structure of the city, are all ignored. This is because planning sees everything as a flat, measurable land, as transactional land. Landform is a very critical factor. Urban design necessarily also responds to landform. Without landform, there is no urban design. What comes out of the landform is a legible structure of the city which is critical to the structure of activities.

You mentioned old Delhi as an example of good urban design. Are there any post-independence cities that come to your mind?

There are only small attempts which have been done. Chandigarh, for instance, attempted to some extent but only at precinct level, not at city level. Most of the attempts in India of urban design are based on this kind of functional approach – of taking a small unit of the city and structuring it in functional and visual ways. Functional and visual are two typical factors, two fundamental ways, to shape relationships between places. So, different entities and their relationship contribute to the meaning-structure of the city. The meaning is vested as much in the elements as in the link between elements.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

You spoke about urban design having the fourth dimension that’s of people and the significance of land form. Can you reflect more on landform and ecology in the context of urban design?

This is all the more important from the perspective of the climate crisis. The current crisis is generated, even compounded, by different forms of planning or land use planning. Ecology and landform are what give rise to urban form whereas town planning reduces it or flattens it where land is measured for transactions. The crisis is compounded because of the idea of measuring land largely as a transactional entity in the city.

Surface water flows are a very critical dimension of any settlement; they were so in all older settlements which did not have any mechanical means of getting rid of the rain/waste water. This aspect is not factored into modern day planning which reduces city planning into an exercise in numbers. All these cannot directly impact the quality of life in the city. How can you touch people’s quality of life with an instrument like town plan? It’s like asking a woodcutter to do an eye operation with an axe, it’s absolutely inadequate.

The transactional background of the capitalist mode of thinking about land as a resource is fundamentally opposed to the idea of a well-structured living environment. That’s why land use planning can be, at best, an instrument to tell you what should not be done rather than what should be done or how it could be done.

How can the community of architects and urban designers seed these ideas to policy makers and governments? Do they listen and engage? What has been your experience?

What comes to my mind is that these are all interrelated issues – urban design, quality of life, ecology, landform, and human actions. There are interactions and relationships between them. If this is the fundamental of understanding of planning and urban design, why is it not reflected in policy or implementation? For this, we have to go back into the history of planning to see how it is genetically handicapped to deal with the issue of quality of life in the city, because it started as a reaction to industrialisation and the subsequent degeneration of the centre of the city. That’s how planning began – as a group of intellectuals coming together to discuss how to make industrial areas and later escape the degeneration of these areas, on how to solve overcrowding and all that was invading the core of the city which meant that people and activities had to be separated, zoned to create ideal communities of suburbia.

That was in history. How do you see it persisting today?

The industrial logic is the basic logic in the planning of cities. We have begun to think of cities as mechanically organised entities, only meant for efficient functioning or for the generation and expenditure of more and more capital, where people have been completely divested from their role in determining their quality of life. Cities have been turned into a mechanical mode of counting numbers with excel sheets, looking at which plot of land can be sold for what kind of profits.

This approach never considered water as a resource except as the visual resource where it is seen as a fine view. Land and water, as primary factors, should guide development but these are not at the core of the industrial logic of planning. It is instead a mechanistic worldview about how efficiently a city needs to function. Efficiency and speed are the parameters. So, we see environmental problems in cities actually springing from this worldview, this mechanistic worldview.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

If we have a city which is totally invaded by automobiles, it creates urban angst among people. There are no places for people to walk, there are no trees because they have been cut down to make room for more and more buildings, more and more infrastructure. It all comes from this worldview. Now, transport planning is like this, only about increasing the speed of vehicles by building more flyovers and making more overpasses and underpasses, all in the name of convenience for people. What it does is inconvenience the citizens because people have to take the trouble of going down and up in an underpass. This notion of mechanised and efficiency framework is opposed to the idea of urban design.

Where would one have to start in order to change it – with elected governments or bureaucrats? Where do we even start talking?

It has to be at multiple levels, it cannot be at one level. One is not more significant than the other. The entire network needs to be dealt with, whether it is the generation of ideas or instruments or planning, whether definition of objective, plans for investments, administrative mechanisms to deliver it. They all require information from the perspective of making the city a bit more human rather than only ‘Engines of Growth’.

We find your work with the Kerala Urban Policy Commission impressive in how it deals with the complexity of urbanisation. Would you give a gist of it and how it could be seen as a model across India?

The identification of problems and the methodology used in the report emanated from the very specific conditions in Kerala which are not repeated in other locations. It is specifically designed for and defined by the type of problems and prospects that the Kerala landscape offers and the perspective of climate change. So, the exact same model cannot fit any other location. But the general principle, the structure and approach can easily be adopted, could be adopted, in other places.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Could you spell out some of the important aspects of the report that could be adapted?

Well, the issue there was to look at the entire state as one planning unit for the next 25 years from the perspective of the climate crisis. There were three specific conditionalities. Kerala’s unique landform, fast changing technology and the climate vulnerability that the state experiences and how, in the next 25 years, it could be combated. I only dealt with one part of it – Habitat and Built Environment. There were a total of 10 verticals from design to finance, economics, health and governance, and so on.

We were able to look at each and use the methodology of talking to different professional groups, user groups, local bodies, institutions, and a large number of people within one-and-half years and arrive at how people identify their problems and what areas are needed to meet their requirements. This was done for all 10 verticals. Kerala, I must say, is very special in the sense that there is already a climate for that kind of public discourse, and Kerala has an advanced local self-government system that’s functioning well. It has had all this for 25 years, an administrative and delivery climate through which something like this can be done. It may not be possible in other states. So, the commission report dealt with existing settlements, coastline, with the reflected sensibilities and needs of the people. The proposals responded to the rising sea levels, ecology to create a schema that includes both people and nature.

Cover Photo: Wikimedia Commons