Sultana Bano, in her late 40s, did not have a choice back in May, when demolition squads razed her jhuggi. An Anganwadi worker, she lived with her husband, a paralytic, in a cluster of slums in the Tughlakabad area in the southeast of India’s national capital, New Delhi, and had bought an air cooler from her meagre monthly earning of Rs 7,000-8,000 to make the city’s infamous heat slightly bearable. When the demolition squad came to raze the cluster, all 3,000 houses in it, Sultana knew she had to forego the cooler that had cost her a month’s pay. “I could only save my husband. Life is more important,” she said.

Bella Estate area, in Old Delhi and to the east of Yamuna river bank, is a quaint neighbourhood with narrow alleys and old houses. Residents of Bela Gaon are mostly old-timers like Rekha’s family of five, with homes that hold memories. In her late thirties, Rekha lived in Moolchand Basti in Bela Gaon. In March this year, Rekha with other residents watched as the demolition squad ripped through the makeshift homes of the Basti and ran the bulldozer over their fields too. When Rekha, heart pounding, demanded to see documents, the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) officials showed her a notice which stated that the area was a part of the ‘beautification drive’ for the upcoming G20 Summit. Unconvinced, she asked them to prove their modest homes were illegal; the officials laughed, she remembers. “Are we collateral damage for this beautification,” she asked, shuddering at the memory of how her home was reduced to rubble.

About 10 kilometres away, Hiralal Jha, 25-year-old resident of the Yamuna Pushta area, was in a worse predicament on June 21. Physically challenged, Jha depended on his neighbours to negotiate life. That morning, he woke up to the sounds of destruction; the demolition squad of the Municipal Corporation of Delhi was on a determined attack against some 350 jhuggi-jhopris and showed mercy to none. His was gone too. “I had begged on the streets to build this house of tarp and wire,” he wailed.

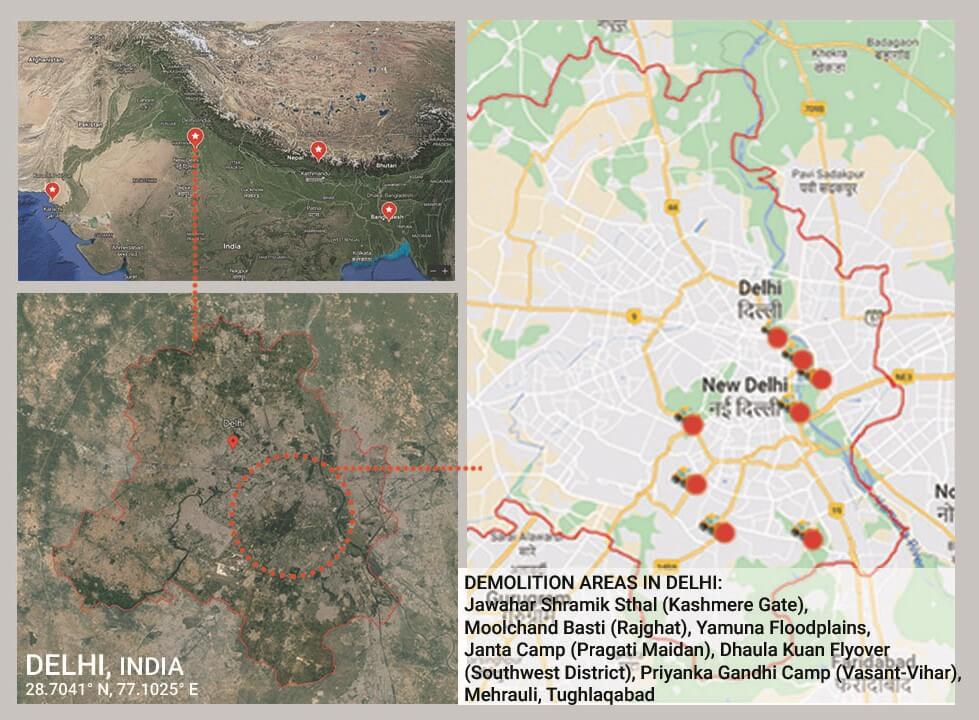

Over four months from March to June of this year, as intense heatwaves seared Delhi followed by devastating floods, five working-class neighbourhoods – all predominantly slum areas – lakhs lived through the worst possible nightmare of losing their homes. The Municipal Corporation of Delhi, run by the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), and India’s national government, led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), began the “beautification” plan for Delhi to get it spiffy and show-worthy in time for the G20 Summit to be held on September 9 and 10. India has the Presidency of G20 this time.[1]

The ‘beautification’ was a cruel joke on the city’s worst-off for whom it meant losing their homes, however ramshackle; the demolitions left nearly 2,60,000 people homeless. Without a clue of what G20 means except that it is some big event for the country or the Prime Minister (seen on hoardings), they were out in the open in appalling levels of heat and floods. The national capital which should have seen climate resilience plans in action during extreme weather events such as these, to provide relief especially to the poor and marginalised in the city, was throwing them to the harsh elements, literally and figuratively.

The G20 is intended to showcase a positive image of the country – and Delhi as its national capital – on the global stage. The price for this has been, and is being, paid by those most vulnerable to extreme weather events and Climate Change impact. Ironically, 23 hotels are being spruced up to house delegates and dignitaries for the G20 Summit. As the demolitions have shown, the government’s pronouncements and claims of climate resilience made on global platforms are hollow. Similarly, climate vulnerability has hardly made its way into urban policy and governance; if it had, thousands would not be dishoused across Delhi.

Map: Shivani Dave

Demolition as a response

This spate of demolitions has been linked to the G20 beautification drive but Delhi has seen demolitions as a routine administrative approach. Termed ‘encroachments’, the jhuggi-jhopdis and slum clusters are easy targets. Between February and July last year, Delhi witnessed several demolitions by the central government: Indian Railways razed 250 homes in Punjabi Bagh without a resettlement plan, evictions happened in Gyaspur where the DDA demolished 100 homes, to cite only two. The High Court, seized of the issue through a writ petition (9625/2022) did not intervene, citing the non-inclusion of these in the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board’s list of bastis.

“Whether for G-20 or not, forced evictions invite gentrification through privatisation and development-induced displacement,” said Rajendra Ravi of People’s Resource Centre. He pointed out in his report that “As is seen in the case of infrastructure and ostensible ‘development’ projects, including road/highway expansion, canal widening, and metro projects, over 77,000 people in 2017 were displaced.”

Other reports highlighted unseen aspects of these demolitions. The Housing and Land Rights Network’s report showed that Muslim slum homes were demolished after communal clashes, such as at Mansarovar Park in May last year, suddenly terming them ‘encroachments’.[2] 2021, it recorded 158 forced eviction incidents across the country averaging 100 homes a day.[3] A report by urban scholar Gautam Bhan, of the Indian Institute for Human Settlements, noted that between 1990 and 2003, a total of 51,461 houses were demolished in Delhi under ‘slum clearance’ measures, and between 2004 and 2007, around 45,000 homes were demolished.[4] However, less than 25 percent of them were resettled.

Under the Indian Presidency, the G20 Summit is focused on the theme ‘One Earth, One Family, One Future’ to affirm the value of humans, animals, plants, and microorganisms and their interconnectedness on earth and in the broader universe. The Ministry of Earth Sciences is popularising Lifestyle for Environment (LiFE) with an emphasis on environmentally sustainable and responsible choices that people should make for a cleaner, greener, and bluer future.[5] During the G20, Working Groups are scheduled to address areas such as green development, climate finance, inclusive growth among others.

Photo: Hrushikesh Patil

Despite tall talk, demolitions were undertaken further intensifying spatial and other inequalities. “What kind of climate justice calls for demolitions of houses? Who bears the brunt of carbon emissions by the super-rich and the West?” asked Anirban Bhattacharya from the Centre for Financial Accountability. However, the DDA denied demolitions for beautifying the city for the G20 summit.[6] In a written reply to Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) Rajya Sabha MP Manoj Kumar Jha, junior minister for housing Kaushal Kishore said that the DDA had informed him this. Facts on the ground belie this assertion.

Heatwave hazards and floods a double whammy

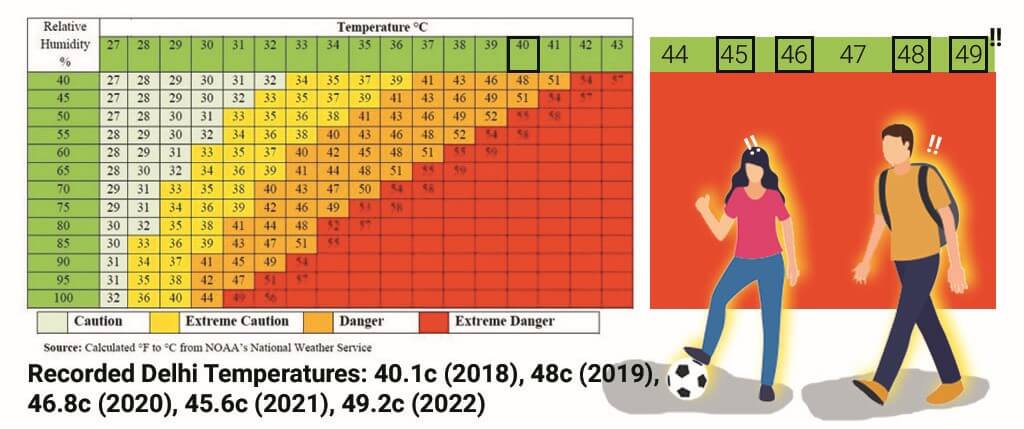

Climate events such as intense heatwaves and floods that have racked Delhi in the past few months only worsen the condition of the poor and marginalised in the city. Reports such as the McKinsey and Company one on climate risk and response in South Asia found that India was at the top of the group of “critical” nations which included China, Indonesia and Pakistan for heat-related threats to their populations.[7] Heatwaves have far-reaching impacts on, among other aspects, food security, and household incomes.

Delhi, a landlocked city, has always had harsh summers. For the past few years, Delhi and the National Capital Region (NCR) have seen temperatures consistently breach 45 degrees Celsius in summer months. The year 2019 saw a maximum temperature of 48 degrees Celsius; the following year, it touched 46.8 degrees Celsius, and in 2021, the highest was 45.6 degrees Celsius. Last year registered a scorching highest temperature of 49.2 degrees Celsius. Temperatures touched 46 degrees Celsius (113 Fahrenheit) this year in May. Combined with relative humidity and other factors, the Heat Index – or the temperature that people feel like – would have been in the 50s.

Such high temperatures would have called for measures under a Heat Action Plan (HAP) but Delhi does not have a functional one for the current year because it is awaiting approval from governments. Even cities which have formulated HAPs struggle to translate the protocol steps on ground during high heat days but the absence of a HAP means that authorities may not even be tuned to provide relief measures given that heat is a silent hazard. The absence of HAP also leads to non-provision of specific infrastructure such as shelters, cooling spots, regular water supply, and outreach clinics to reduce the impact.

Illustration: Shivani Dave

While Mohalla Clinics provided some health-related support, this team did not find any other measure in place during the high heat days “There is no communication between the government and urban poor on the risks of heatwaves. Heatwave precaution guidelines are available on government websites and social media, but do not reach people who cannot access these though they are most vulnerable,” pointed out Akshit Sangomla, a writer on environmental issues.

Floods mean the same set of challenges for the poor. Through July, Delhi was grappling with one of the worst floods in 45 years as the Yamuna breached its danger mark. Several people living in the low-lying areas had to be evacuated and housed in shelters. Those in bastis struggled to simply stay alive; those whose homes had been demolished were literally at the mercy of nature.

Kalpana Devi, in her 30s, stands straddling her one-year-old daughter outside the makeshift shelter on the footpath leading to Shastri Park Metro station. The baby suffered from heat rash. When the Yamuna flooded on July 13, Kalpana Devi and many like her from Yamuna Khadar were not warned about the rising water levels. “My husband had gone out for work. I somehow took the kids, some home essentials, and made my way through waist-deep water,” she said. When the flood washed away her jhuggi, she lost even personal documents without which she cannot avail government’s flood relief.

Photo: Sejal Patel

Like other families, she too was not allotted temporary shelter by the district collector office; instead, they were all provided with a few tarpaulin sheets and foodgrains by an NGO. Prem, who lived in the same locality and earns Rs 250-300 a day as a daily wage labourer, ended up spending Rs 1,500 on a pathology test at a private lab. Ishrat, a teenager displaced by the floods, saw her jhuggi demolished in Yamuna Khadar in March during the ‘beautification’ (demolition) drive. She somehow managed to rebuild her hut but it washed away in the floods. Similar stories abound here. Most families are migrants from remote areas of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, setting up ‘homes’ in the neglected subserviced parts of the city, vulnerable to demolitions as well as floods.

Known housing problems, ignored solutions

The Delhi government’s department of environment, in charge of preparing the State Action Plan for Climate Change assessed that the south and northeast parts of Delhi are most vulnerable to Climate Change impact though research at Cambridge and Yale University showed that all of Delhi is at dangerous Heat Index levels.[8] Another study referred to the Delhi SAPCC 2022 but the plan itself is currently not available on the website of the Delhi government.[9]

Besides this, the district-level Heat Index research shows that even low climate-vulnerable areas of Delhi are at high heatwave risk. The SAPCC 2017, used currently, does not factor in the Heat Index; without this, relief measures and warning systems cannot effectively plan for the full impact of a heat wave, especially on the urban poor. Their vulnerability increases manifold when they are left without a roof over their heads after demolitions. India makes an assessment of climate vulnerability – there is a national Climate Vulnerability[10] Index — but it does not consider factors such as affordable housing for urban poor to map heat-induced vulnerabilities.

Without structural solutions in the housing sector, which makes affordable housing a priority, reducing climate vulnerability of the urban poor is a mirage. According to the Economic Survey of Delhi 2022-2023, “about one-third of Delhi lives in substandard housing, which includes 675 slum and JJ Clusters, 1797 unauthorised colonies, old dilapidated areas and 362 villages. These areas often lack safe, adequate housing and basic services. According to the projections, Delhi needs 24 lakh new housing units…of these, 54 percent are required for the EWS and LIG.”[11]

The numbers are staggering. The jhuggi basti and slum clusters are home to 1.7 million people, often called ‘encroachers’, the unauthorised resettlement colonies house nearly four million, and the notified slum areas or katras have nearly two million people living thousands of them with a ‘perpetual licence’ providing a fragile shield against demolition. Besides, there are 135 urban villages and nearly twice that number awaiting a formal transition from rural, and there are around 16,000 homeless and pavement dwellers entirely at the mercy of governments.

Photo: Hrushikesh Patil

It is a complex landscape of people and housing, especially at the lower end of income – at once a complex story of urban growth including the provision of affordable housing (or the lack of it) and multiple stories of some of the poorest urban families dishoused and dispossessed for lofty city beautification programmes. There is a human cost of such ‘beautification’ – for G20 Summit or any other purpose – and it is paid by those who can least afford to, who anyway have very little space to call their own.

There will be discussions and mentions of Climate Change during the G20 and later at Conference of Parties COP28, there will be the usual talk of making India climate resilient and reaching the most vulnerable and so on, ‘climate targets’ will be set and carbon set-offs decided. All of this sounds hollow and meaningless to the lakhs whose homes were razed, homes they had ‘built’ where they could because affordable housing and climate-resilient housing are beyond their mindscape. Without adequate housing and other basic services, climate resilience and targets are just hot air – all talk, no action.

Climate Change stamped its presence all over Delhi twice this year – in unprecedented heat and record-breaking floods, hitting and displacing the poorest some of whom also bore the brunt of demolitions. Climate justice must mean rehousing and rehabilitating them as well as providing adequate affordable housing for all.

Hrushikesh Patil is a Maharashtra-based independent journalist and environmental lawyer interested in covering the impact of Climate Change-induced disasters on vulnerable communities. Currently working with the Goa Foundation as lawyer and researcher, he is also a member of the environmental communications and advocacy volunteer collective called ‘Let India Breathe’ and is a recipient of many awards.

Sejal Patel, an independent journalist and documentary filmmaker currently working from Delhi, keeps a strong research focus on rural communities and data journalism, as well as the application of artificial intelligence (AI) to the fields. Patel holds a postgraduate degree in Convergent Journalism from AJ Kidwai Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia. Through her work, she aims to challenge established norms, foster social justice, and instigate transformative change.

This is the first part of a series supported by the QoC-CANSA Fellowship to report on Climate Change and cities in four nations of South Asia.

Cover photo: Demolition drive razed tubewells built by Bella Estate residents. Credit: Hrushikesh Patil