India’s capital Delhi lives with the tag of being the most polluted city in the world. The old and historically-layered city, known for a host of reasons from food to monuments and Central Vista to poor safety for women, has another qualifier – pollution. The city’s air quality is hardly anything to preen about but come winter and the city starts experiencing rapidly deteriorating AQI levels forcing its nearly 20 million residents to ingest an increase in pollutants.

The focus continues to be on air pollution. Its impact on the health of Delhiites gets an airing but the linkage between pollution – both air and water – and deterioration in public health especially of children and the elderly is not made as strongly and repeatedly as it should be. Now, the data is irrefutable – the pollution in India’s capital is hurting the health and well-being of its citizens, the smog bringing on breathlessness forcing schools to shut down and pushing air purifier sales. Such private fixes rarely help; millions in the city do not have a proper house to live in which makes an air purifier a distant dream.

Why does Delhi struggle and suffer year after year? How seriously are the health impacts of the consistently exacerbating levels of pollution?

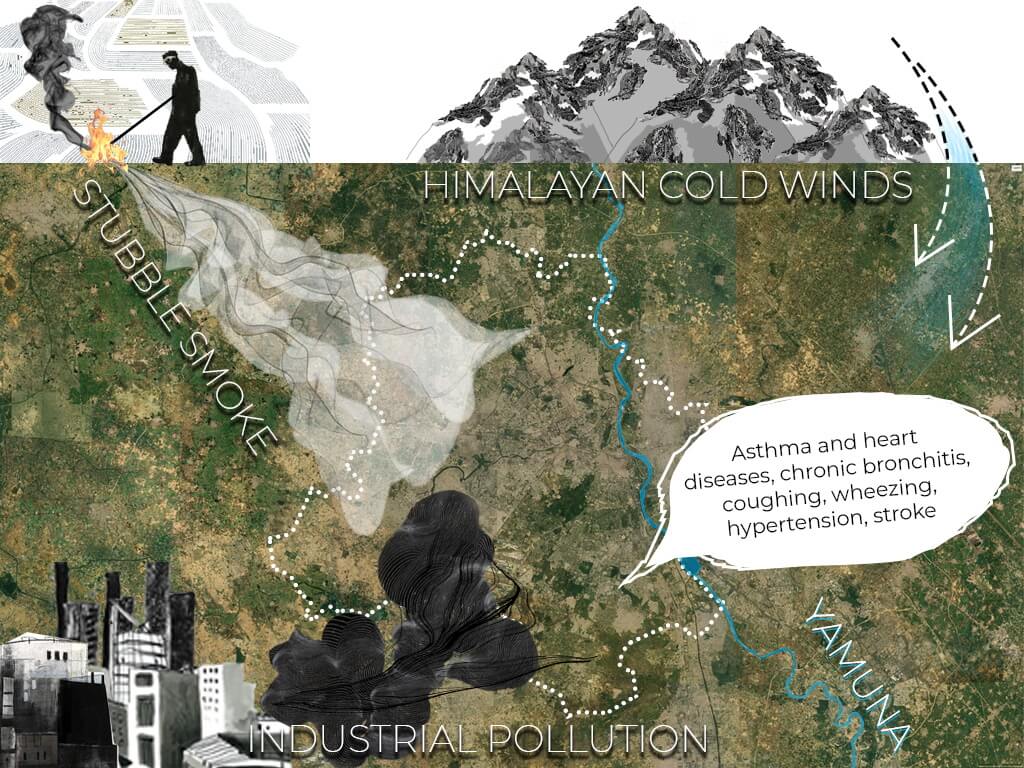

Take a look at where Delhi is situated. It is located on the northern Indian plains with the River Yamuna towards the east and the Delhi ridge originating from the Aravalli Range towards south and west. Delhi is landlocked between the Himalayas on one side and the vast farmlands of Haryana, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh on the other. Smog from the stubble burnt in the neighbouring states contributes to the hazardous air pollution levels but local sources were far more responsible for the dangerous air; vehicular emissions were responsible for 51 per cent of the PM2.5 level in October.[1] The Himalayas do not allow this hot air to escape and it forms a layer over the cold of the winter.

Delhi’s borders are lined with industries, large and small, that discharge effluents into the air and into water bodies, mainly the Yamuna River. Inside Delhi, vehicular emissions, cow-dung cake combustions, exhaust from diesel generators, emissions from small-scale industries and dust construction work only make the smog layer denser. Studies show that inhalation of any kind of particulate matter can result in coughing and wheezing to asthma attacks, hypertension and stroke. Delhi’s air is polluted not just with particulate matter but with lust for power which gets manifested in its built environment in many ways.

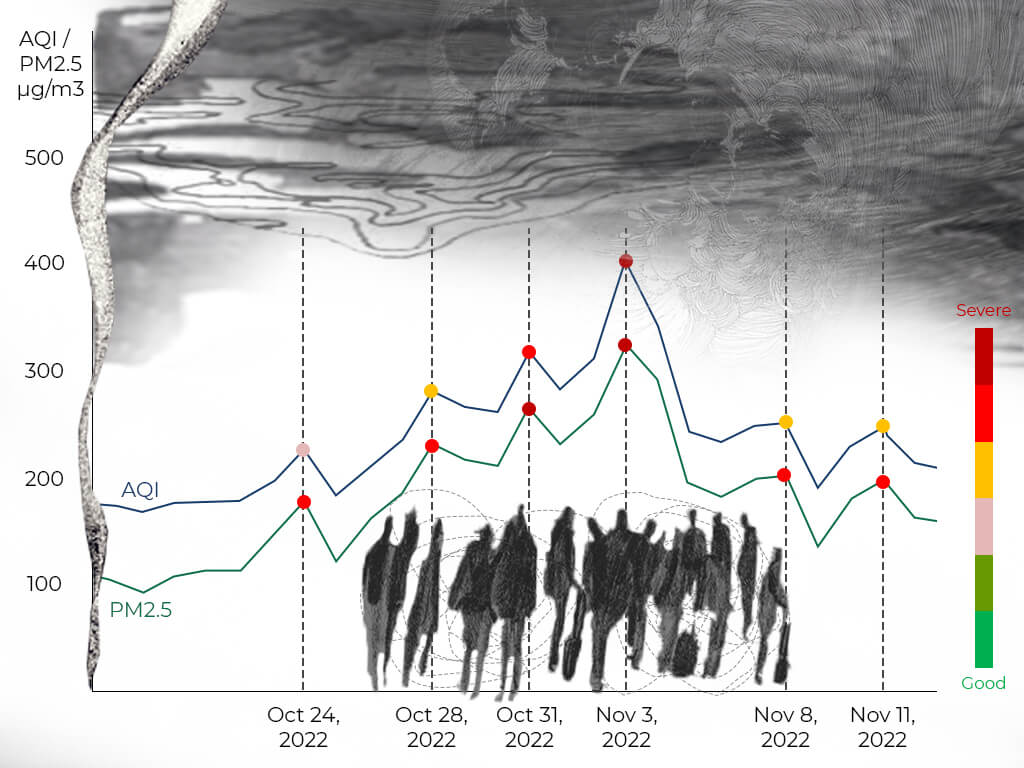

In the last month, Delhi’s AQI and PM2.5 levels have consistently been either ‘very poor’ or ‘severe’. According to data collected by Praja Foundation from the Central Pollution Control Board(CPCB), Delhi had only five ‘good’ AQI days between 2015 and 2018. High levels of air pollution in Delhi reflect in the poor health of its residents. In 2017, respiratory diseases were the cause of 8.4 per cent of the deaths in Delhi. The year 2016, which had 126 days of ‘poor’ quality air saw the deaths of 11,900 people from respiratory diseases. Between 2015 and 2018, the city saw a steady rise in cases of malignant neoplasm (cancerous tumour)of respiratory and intrathoracic organs and other diseases of the respiratory system.[2] These numbers are telling of just how severely pollution can impact health.

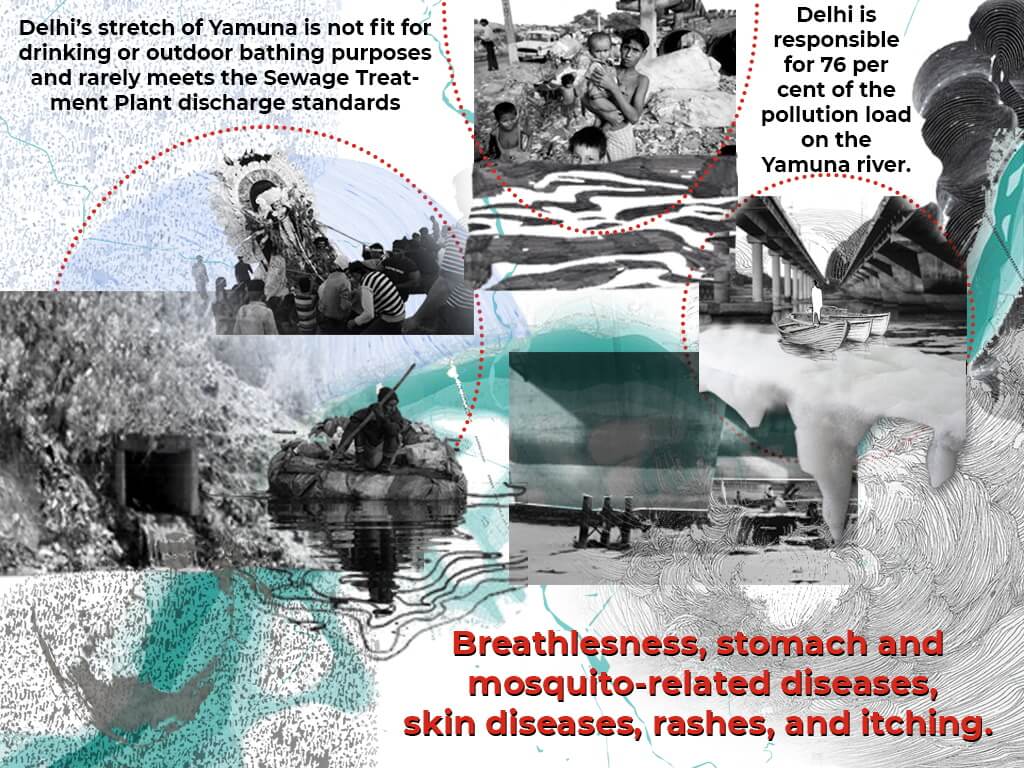

If the air pollution gives Delhi a dubious tag, water pollution is not far behind. Delhi’s life-giving river, the Yamuna, continues to be turned into a drain with the city’s sewage – most of it untreated – and industrial effluents severely impacting its flow and ecology as well as the health and well-being of people who are among Delhi’s poor. Only two per cent of Yamuna’s length flows through Delhi, between Wazirabad Barrage and Okhla Barrage, but the city is responsible for 76 per cent of the pollution in the river.[3] The stench from the river causes breathlessness among the people who live around it. Gastroenteritis, diarrhoea, mosquito-related diseases, skin diseases, rashes and itching are some of the health issues that the residents living in the river’s vicinity have to put up with.

A study published in peer-reviewed medical journal Lancet stated that Delhi suffered the highest per-capita economic loss due to air pollution in India in 2019. The study by Praja Foundation has also found that in 2019, residents in Delhi spent 9.8 per cent of their family income on health. This percentage was found not to vary across socio-economic classes. The study however, could not attribute the amount of stress that it would place on someone from lower socio economic classes and the impact of the available subsidised services in the capital. The annual expenditure on health was found to have increased between 2015 and 2018.

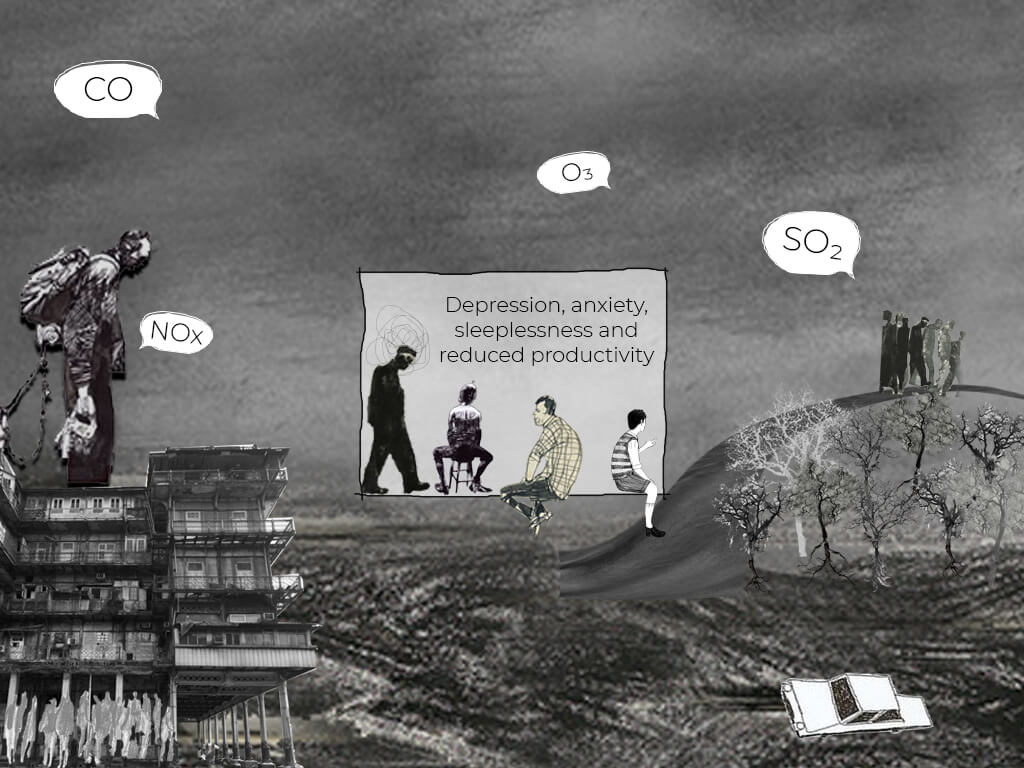

Pollution also has costs beyond physical health. People living in polluted areas undergo stress that manifests itself in the form of mental illnesses. Pollution also impacts people’s productivity levels. Either sitting cooped up indoors or being exposed to pollutants when one steps out can lead to people engaging in impulsive and risky behaviour as a result of short-term depression, sleeplessness and anxiety.

In another study published by The Lancet Psychiatry in 2017, it was found that in Delhi, life years lost to death or lived with depressive disorders and anxiety disorders was calculated to be 459 years and 321 years in an average of 1,00,000 years respectively. There aren’t any conclusive studies that point to the relationship between mental health and the pollution in Delhi experienced by its residents everyday. However, there are many other countries conducting researches to indicate that poor quality of air and water have profound and long-term impacts on the mental state of individuals.

Between 2017 and 2021, students in Delhi lost a median of three days of school, which increased to seven days in 2021, due to air pollution. In 2019, though schools were shut for five days due to pollution, the winter break had to be extended by eight days owing to the poor air quality across the city. This year, the government enforced Stage 4 regulations of the Graded Response Action Plan(GRAP) for five days beginning November 3, effectively shutting schools down for the period. Just how severe the pollution is can be gauged from the fact that children are not being allowed out in the open, in schools.

As Delhi grapples with a plethora of programmes to address air and water pollution, its residents – the poor more than wealthy – take the knocks every day in their life, at work, in their health and well-being. In the multitude of discussions on pollution, its impact on health needs a stronger focus. The health implications of ingesting particulate matter and polluted water, and the long-term effects of living in the world’s most polluted city needs deeper study. The impact on the marginalised is bound to be more acute considering their greater exposure to pollutants and fewer means to counter its impacts – they cannot afford to buy bottled water and air purifiers.

As the deadline for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) come closer, all eyes are on Delhi to see how it makes its way out of the smog to provide residents with a safe, clean and sustainable environment.

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Maitreyee Rele graduated from School of Environment and Architecture (SEA) in 2021, where she mostly chose to work on projects on a larger urban scale. She is interested in studying people, their cultures and the society in which they unravel. An unfathomable love for films, art and every other form of storytelling make up the rest of the being.