Withdrawn and sulky

I flow past Delhi,

like dark silver

caressing the city shores,

draining darkness

from Delhi’s soul.

This is the lament, a moan, of the Yamuna River that poet Abhay K gave words to in The Seduction of Delhi (2024).[1] For a river on whose banks and generosity, Delhi flourished century after century, was built and rebuilt, to be morose and angry is a call of desperation – a call to recognise its significance in a city that seems to have all but turned it back on the river, a call to renew its health and restore its ecological vitality, a call to reconnect with all the people who make the city.

But who is listening to the river’s call? Why should the people of Delhi spare a thought and dime for the Yamuna? How does it feature in the city’s plans, and, importantly, can Delhi make the leap to centre the Yamuna in its planning?

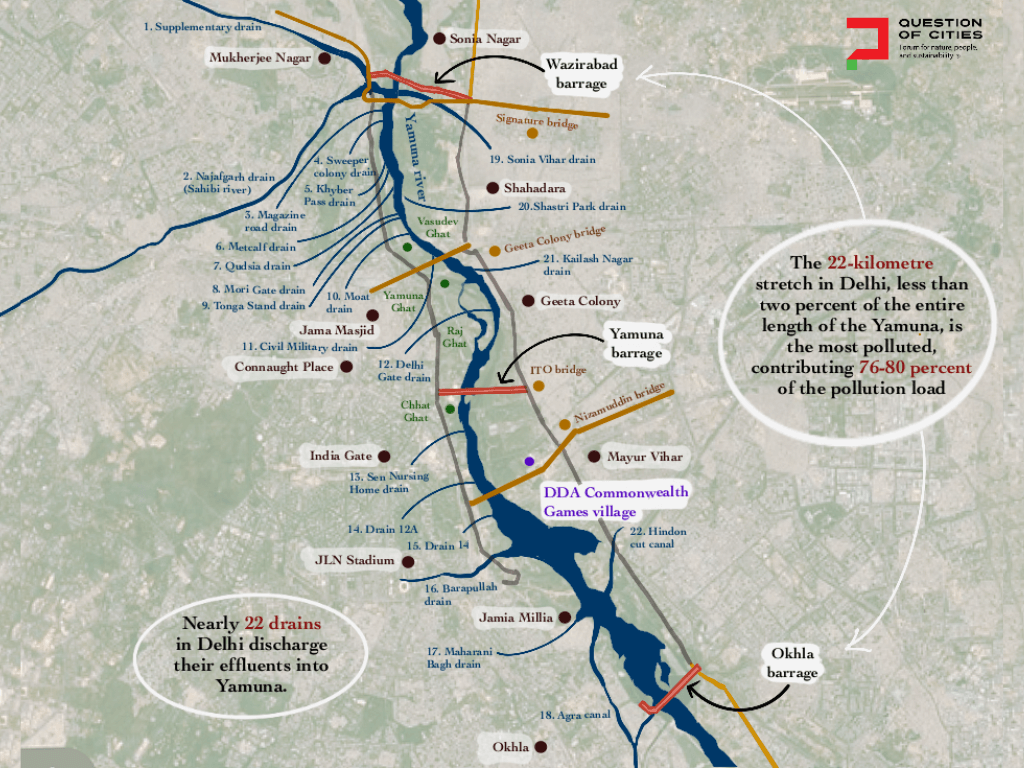

The Yamuna in Delhi has been declared dead[2] for quite some time now. Originating in the Yamunotri glacier in Uttarkashi, it meanders across 1,376 kilometres in four states before meeting the Ganga. Only 52 kilometres of it flow along the National Capital Region from Palla to Jaitpur. Of this, barely 22 kilometres streams through the city of Delhi from Wazirabad to Okhla Barrage but this small two percent of the mighty river carries 76[3] to 80[4] percent of Delhi’s pollution load.

For decades now, the river has received untreated sewage, industrial effluents, and toxic chemicals leading to dangerously high levels of biochemical oxygen demand, faecal coliform, and heavy metals all of which has damaged its ecology, turned it into a carpet of toxic foam, and made the river unsustainable. It is also Delhi’s primary source of water supply via the Western Yamuna Canal and Munak Canal from Hathnikund Barrage.

Photo: Ankita Dhar Karmakar

Despite multiple action plans launched since the 1990s[5], the Yamuna has veered between being Delhi’s resource and its sewer while its floodplains became real estate for the ever-expanding city. While the upstream Wazirabad Barrage shows a relatively larger floodplain area, the flow has been found severely disturbed in other places including Shastri Park and Yamuna Bank Metro Station.

After decades and crores spent on numerous action plans, what Delhi is left with is a dangerous dichotomy and socio-ecological inequalities about the Yamuna – massive constructions on the floodplains such as the Commonwealth Games Village, the Art of Living festival, and the Yamuna Riverfront Development project while modest informal settlements and farmlands where farm labourers, fishermen, boatmen, divers, priests struggle to make a living are demolished. The people who power Delhi’s daily rhythms, who settled here during the Partition or migrated for livelihood, in the Yamuna Pushta slums and beyond, evicted to ostensibly free up the floodplains.

The Yamuna has quietly watched these selective, exclusionary and socially divisive actions. Its “withdrawal and sulk” are signals that Delhi has ignored – or failed to read.

Plans, ecology and people – an interconnection missed

The restoration of the Yamuna depends not on riverfront development – which means more construction and concretisation – but on rejuvenating the river ecology that begins with respecting and understanding it, as veteran crusaders of the river have pointed out. It includes ways to integrate the river into city planning and city making that discard the old way of seeing a river in the city as an afterthought, an annexure to its detailed land-use plans.

Delhi’s plans have acknowledged the Yamuna but it’s complicated. The Master Plan of 2021[6] carved the city into 15 zonal areas and marked the entire floodplain area of the Yamuna along its 22 kilometres as Zone O. An estimated 56 bastis with roughly 9,500 households – perhaps more – lived in this zone, mostly new migrants and farmers who had been here since the British era; some illegal but mostly legitimate. Cases of ‘encroachment’ went to the courts and demolitions followed. But these settlements have carried out nature-based activities as livelihoods that have had a low ecological footprint, environmental and social activists pointed out. Yet, in the guise of preventing pollution and protecting the ecology of the Yamuna, they faced evictions or lived with the threat.

Delhi’s Master Plan 2041 bifurcates the floodplain zone into two – Zone OI and Zone OII – and prohibits construction in the first while allowing it or regularising it in the second. The Commonwealth Games Village, the Akshardham Temple, large tracts of the riverfront development including on the Millenium Bus Depot stretch which the Supreme Court had ordered demolished, and other ‘beautification’ projects lies in Zone OII.

If “Delhi’s soul” must be preserved, then its politicians and planners must engage with the question: how is it sustainable for the well-appointed classes to enjoy at the constructed riverfront but not sustainable for marginalised people with a history of living on its banks and bonding with the river to continue living there? How are the latter held responsible for pollution when reports show that untreated sewage and industrial effluents are the main culprits? The answers might be beneath the toxic foam and dark sewage, if they cared to look. But in the myopic vision that Delhi’s politicians and planners have shown, cleaning the Yamuna and restoring its ecology has been equated with identifying ‘encroachers’ and carrying out demolitions – often with the backing of the courts.

Photo: Sudip Sen

While the spate of demolitions goes back to the 1970s and the Emergency, the targeted demolitions to save the river are more recent. In March 2003, in a petition by the Wazirpur Bartan Nirmata Sangh versus Union of India that asked for slums to be removed from industrial areas, the Delhi High Court ordered the demolition of the Yamuna Pushta settlements too. The slum dwellers, it justified, were the main contributors of the river pollution. In December that year, after months of resistance by the people, the demolitions were carried out and people sent to Delhi’s outskirts like Bawana and Madanpur Khadar; over the years, some returned.

Tensions lingered across the settlements. In 2020, the National Green Tribunal ordered the removal of encroachments in the Okhla area of the floodplains; in September that year, bulldozers of the Delhi Development Authority razed the slums at Dhobi Ghat, Batla House. In 2024, the Delhi HC again ordered, on a petition that linked the city’s worsening air pollution to unauthorised construction, the removal of “all encroachments and illegal construction on the Yamuna river bank, river bed and drains flowing into river Yamuna” rapping the dwellers with a stern “do not shed crocodile tears”.[7]

What is authorised and what is not, and how lightly or harshly the unauthorised should be dealt with is a matter of social station and influence. How else can this be explained? Even as the demolition cases went on in the courts, in 2016, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar’s Art of Living was allowed to organise a massive World Cultural Festival on the Yamuna floodplains. Following a ruckus, an expert panel of the NGT recommended that the spiritual organisation be fined Rs 42 crore for physical and ecological repair of the floodplains but the NGT lowered it to merely Rs five crore.

Clearly, those who can pay can pollute; those who cannot must endure demolitions. Over the years, lakhs[8] of slum-homes have been demolished in the Yamuna Pushta region, mostly for the beautification of the city. “This is the logic of neoliberalism which prioritises aesthetics over the welfare of its slum dwellers,” points out this research paper.[9]

River-led planning as the future

Restoring the river and its ecology has come to mean riverfront development or ‘beautification’, though they could not be more divergent. Delhi was designed around the river banks in the 17th century when the Yamuna fed[10] the canals that cooled royal palaces. Colonial making of Delhi, historian Swati Janu argues[11], fractured the geomorphology and human ecology, buried streams from the Ridge under grand avenues, and turned nullahs into sewers. The river was screened off by high walls, and enclosures, from the city, left only for the spectacle of the elites, write[12] academicians and researchers Dr Reema Bhatia and Meeta Kumar.

Riverfront development symbolises, in the new India, purposeful action and spectacle that’s supposed to showcase the river but this approach – not just in Delhi but across India’s cities – is repeatedly imagined as top-down planned construction along the banks, sidelining of the river’s hydrology and ecology, eviction of the existing low-ecology-footprint users or the marginalised. The Yamuna, as noted sociologist Dr Amita Baviskar calls it, has become a ‘non-place’, emptied of any social meaning only to become real estate.

The river ought to be centred in the city’s plan. Centering would mean, for example, allowing the river to guide land-use and construction policies. It would call for understanding the river as a composite and complex ecosystem beyond just a water source or dumping ground; ideally, not just an ecosystem but “a living and breathing entity”, as Dr Bhatia and Kumar tell QoC in this interview. To see it as a composite ecological whole should not be a tall task but it is, as the late Manoj Misra, Indian Forest Services officer and environmentalist who set up Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan frequently pointed out. Misra counted as many as 16 agencies in charge of the river in Delhi.

If the plethora of agencies and vast sums of money were enough to restore the Yamuna, the story would have had a happy ending by now. Money has consistently flowed for river cleaning. Between 2022 and 2025, Rs 5,536[13] crore was spent. In Nov 2025, thousands of crore were earmarked from the Namami Gange Programme. On Jan 29, 2026, Chief Minister Rekha Gupta approved projects worth Rs 728[14] crore to boost civic infrastructure along the trans-Yamuna area.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

However, institutional challenges persist as much as a lack of an ecologically-led vision. The Yamuna in Delhi has 37 Sewage Treatment Plants, of which only 17 are functional.[15] Delhi generates[16] 11,862 tonnes of solid waste every day but 36 percent is not processed, according to Delhi Pollution Control Committee. In August 2025, the NGT asked[17] IIT-Delhi to check on the safety of the sewage discharged into the Yamuna but, to date, the IIT-D has no data because it has not been able to gain site access[18] to review the Sewage Treatment Plans.

Yet, the blame for the pollution falls on the people living on its banks – authorised and unauthorised. While the cleaning efforts and the creation of ecological breathing spaces such as biodiversity parks symbolise the idea of ecological restoration, it runs deeper. Delhi’s floodplains have been consistently shrinking, which dangerously threatens[19] the Yamuna’s carrying capacity.

The challenge would be to leap beyond all this to create and embed a vision centred on the river in a city. This would mean clearly delineating the floodplains, marking strict no-development zones or non-negotiable areas where construction will not be permitted, putting down flood lines for one-in-25-year and one-in-50-year floods that allow the river to swell without bringing urban floods, mapping and protecting the complex biodiversity and non-human species that the river supports, and charting out its protection. Essentially, this vision calls for seeing and treating the Yamuna and all water bodies as the city’s natural wealth.

This is truly a river in a city or river by a city – recognising it not merely as a utility or project area but as the city’s natural asset that shapes its urban form and plan.

Just how far this lies shows a study by the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA) in 2020. Half of the 13 cities studied “did not have any vision centred around the river despite having ecologically significant river systems running through them…Chennai stood out as an exception for its thoughtful integration of water into its urban plan”. According to the NIUA’s Ishleen Kaur, senior environmental specialist, the Delhi Master Plan 2041 has attempted a major shift. “We made a conscious decision to put the Yamuna and its floodplains at the centre of the environment strategy,” she said.[20] This included detailed baselines for physical infrastructure, water supply and sewage, and ecology which encompasses restoring 250 water bodies, formally delineating floodplains, and expanding green-blue networks.

But the focus on the Yamuna may not be enough. The Sahibi River is a major contributor to the pollution, without addressing which the Yamuna cannot[21] be cleaned. In the 2022–23 budget, the Delhi government allocated Rs 705 crore for cleaning the Najafgarh drain; in May last year, Rs 600 crore project to build a road and riverfront along a 60.77-kilometre stretch was rolled out. Again, this is construction on the riverbed or floodplains.

International cities have recognised that the health and integrity of the river in a city means a renewed city itself, made plans to restore the river and turn it around. The Thames[22] in London and the Chicago Riverwalk[23] in Chicago are but two examples. It begins with people in power nurturing an ecological vision, having the humility to recognise that the city cannot truly flourish when its rivers darken and die. Who in Delhi’s corridors of powers has this vision or humility?

Ankita Dhar Karmakar, Multimedia Journalist and Social Media in-charge in Question of Cities, has reported and written at the intersection of gender, cities, and human rights, among other themes. Her work has been featured in several digital publications, national and international. She is the recipient of the 4th South Asia Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity and the 14th Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity. She holds a Master’s degree in English Literature from Ambedkar University, New Delhi

Cover map: Nikeita Saraf