Natural areas in cities are under the constant threat of ‘development’ that flattens and builds over them, contributing to the rising incidences of heatwaves and floods. This also disconnects people from nature in cities, often even unaware of the natural wealth around them. One way to create awareness and rebuild the relationship between people and nature is by mapping these areas. Mapping has become popular of late but simply mapping natural areas does not suffice, explains urban researcher, teacher and geospatial mapping expert, Abhijit Ekbote.

“Once you document green spaces and put them on a spatial system, you should put it on the ground for people to interact with it, where people can pause. This helps them connect with nature in their surroundings,” he says in this interview to Question of Cities. Ekbote talks about the ways in which such knowledge of natural areas can be used to empower people and also help to reimagine cities that can be built harmoniously with nature. He runs City Resource[1], a platform of geospatial data which is not easily available in the public domain. His research includes the understanding that building on elevated natural areas and mudflats can be dangerous for the future of cities, especially cities like Mumbai.

How does the mapping of natural areas help in the planning of our cities?

The planning these days is top-down where master plans and development plans are made for people. These do not pan out the way that they are supposed to because the ground realities are not thought of. The nuances of small localities and neighbourhoods are missed. That’s why you see that less than 10 percent of Mumbai’s Development Plan is implemented on the ground. Local area planning, which was a great idea, unfortunately was scrapped. Concepts like those may be the way forward.

We are experiencing climate disasters which are connected to the way our cities are planned. Cities have completely ignored natural resources. This is the biggest problem we face now. Rivers are called nullahs in our plans and treated as backyards. Where a river enters a city, drain pipes and filth are directed to it. We see this right outside Mumbai’s Sanjay Gandhi National Park. Rivers and wetlands are neglected, mangroves and mudflats are ignored. Because of extensive building on mudflats, too much extraction of groundwater, and building close to rivers and wetlands, we find that our cities are sinking.

What has been a significant finding for you from maps?

When I overlaid the present-day informal settlements of Mumbai on the 1827 map of Bombay[2], I realised that they have come up in areas which are extremely vulnerable to disasters – either on steep slopes or extremely low-lying areas which are flood-prone. This means more than 80 percent of the informal settlements are in extremely hazardous areas, if you leave aside informal settlements close to gaothans which are safe havens. The manner in which urbanisation has taken place in Mumbai, it is clear that the areas which flood today were softer landscapes earlier, as seen from this map [3].

Why is it important to map natural areas in cities?

We know that we need to protect natural areas in our cities because we can exist only if nature does. So, they definitely have to be mapped. When we make ecological maps, we create evidence and document it. This is useful for researchers and planners to work with. Geographic Information System (GIS) can help us analyse land cover and help us do historical land cover mapping, as well as current mapping, and then compare the two. Other powerful platforms like Google Earth Engine, which is a cloud-based platform, does not require us to download heavy files on the machine which adds to the convenience of using GIS.

If information about natural areas is made freely available to people, does it impact the way in which people view and interact with the city?

Mapping a city’s ecology can radically change the way we see development. Once people look at natural systems, organisms and their habitats, they realise that there is a continuity in the life process that sustains them and insensitive ‘development’ can disturb this. For example, when the residents of Mumbai’s Lokhandwala Complex knew that there are mangroves around them which need to be protected, they became sensitive towards them. They are also thinking of making boardwalks now. The moment you give access and knowledge to people about natural areas, you empower them to make decisions about how to protect these areas.

Once the green spaces are documented and put on a spatial system, this should be available for people to interact with. One way to help people identify natural resources around them is to use simple signages or information placards. Softer interventions like creating seating areas where people can pause can help them connect with nature in their surroundings. Also, if the data about natural areas in cities is put up on a web-based platform, or a dashboard, which is dynamic and continuously updates people about the condition of these areas, including how many are being destroyed, people will be aware and motivated to raise their voice to save these spaces.

Does having such information open people’s imagination of cities?

If the information is available on a ready platform, people will definitely use it to raise their voice and act against exploitation of natural areas. Building at higher elevations on steep slopes causes erosion that blocks the rivers and leads to siltation. If we extract groundwater indiscriminately, sinking will happen. If we build on mudflats, we will lose the sponges. Once the areas that cannot be built upon are identified or the areas where we cannot draw groundwater from are known, all such activities can be stopped. If this happens, I think we will have some hope. Seoul built a highway over a river but also realised its mistake and restored the river later by dismantling the highway. If Seoul could do it, any city can.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Community participation in mapping has turned into ‘maptivism’? How do you see this?

Community participation is important in mapping natural areas. One needs to involve the community of a place that’s being mapped and teach them to map. You should not have a preconceived notion of a place, create a data collection form, and then go out. Capacity building is also something we need to do. Citizens who are interested in this work can be taught the basics and they can take over platforms themselves. Instead of activists managing platforms, people can be empowered in groups to come together and manage these platforms. After the mapping, people can create their own web maps and action plans, and that’s how natural areas can be protected through community mapping.

What has been your experience of teaching this to people?

We had undertaken a participatory mapping exercise in Saloshi Gaon, near Koyna Dam. The intent was that the women and men come forward and learn how to geotag natural resources and their farming practices in their village so that they can be shown on a map and then protected. It is important to involve women in all these activities as their issues and concerns get completely side-tracked. We did a similar mapping in Dharavi too, where we mapped amenities and ensured that there was women’s representation from each nagar (colony).

Heat and flood have wracked cities recently. Mumbai grapples with floods every year. What is needed to make Mumbai flood resilient?

Firstly, the kind of ground surface treatment needs to be controlled in such a way that it has a low run-off coefficient. This means that the ground surfaces should not be concretised. Secondly, roof and surface rainwater harvesting has to be mandatory for large plots as well as small plots. Thirdly, the way we treat our river edges needs to change. In spite of the Chitale Committee Report prescribing gabion walls which allow for percolation, concrete retaining walls have been made with large footings that go into the river bed. These don’t allow for any kind of life. This means a loss of habitat for birds like the Common Kingfisher who have their nests on river banks. Tall walls don’t make sense, they are to show that something is being done.

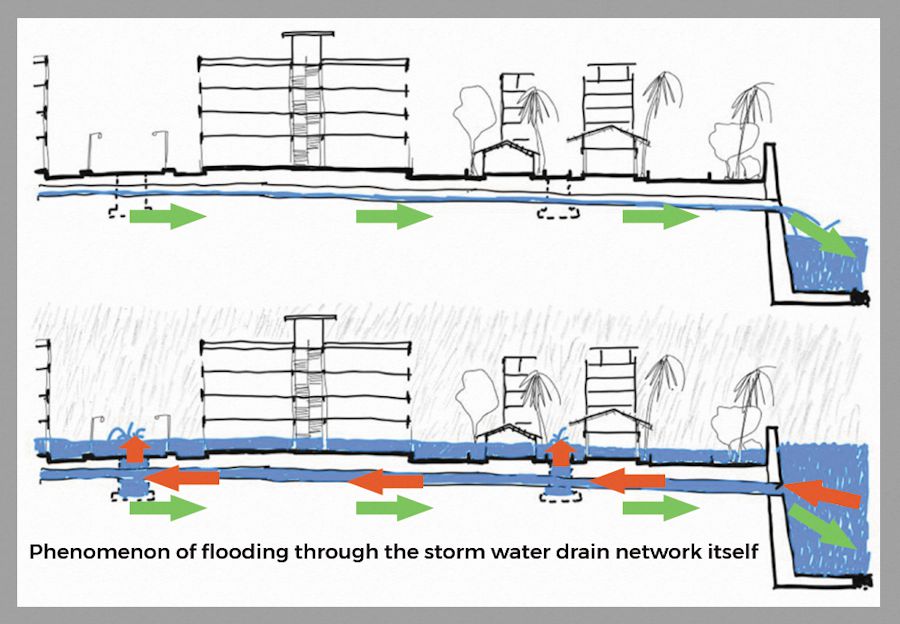

Fourth, the authorities fail to understand that even if they can raise the height of RCC retaining walls of the river (before every election), excess water will still enter the city through the storm water network itself. The valves which are supposed to prevent the backwater coming into the city through the storm water drains are not functional, as seen in the Figure 1 below.

Lastly, to increase resilience, early warning systems have to be in place. We only have general yellow, orange and red alerts now; we need a more localised granular weather monitoring and early warning system. I have developed a simple mobile friendly map [4] which tells you whether you are in or around a flood prone area. If you know this, you will try to reduce the damage by preparing in advance.

What are the immediate measures Mumbai should take to control urban floods?

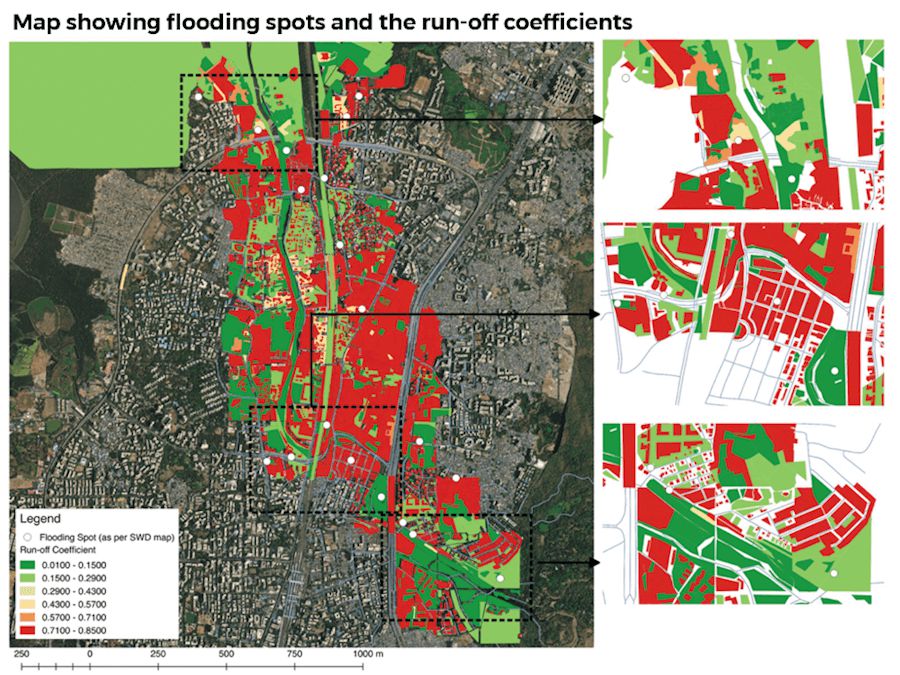

Interesting observations came from a student workshop done in collaboration with World Resources Institute conducted at Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture (KRVIA) that studied surface conditions and mapped flood-prone areas through GIS. Newer areas which are hard landscapes have raised levels which leads to flooding of older areas that are on softer land. Older areas with ground plus two three structures and bungalows which have ground surfaces exposed get flooded whereas the new towers which have come up don’t flood – they are the cause of the flood, as seen in Figure 2 below.

At a larger level, the entire city is built on water [5]. When you talk to the storm water department about floods, they say that “pura city toh paani ke upar bana hai, hum kya kare? (the whole city has been made on water, what can we do?)” In that case, if this is true, then why are the ward boundaries not matching the watershed boundaries? If these boundaries are watersheds, we should have had development plans around water.

Building disaster resilience is important. Safe routes and safe zones should be highlighted on maps accessible to people at all times on their mobiles so that in case of a deluge, they know exactly which route to take and where to take shelter to save their lives. Interventions in combination with each other are necessary for all cities.

You also teach in architecture colleges. Do you believe that workshops on these themes would be beneficial for students who ultimately design cities?

Architecture does not happen in isolation. We only realise this once we move out of college and practise on the ground. Your building is one small jigsaw puzzle piece in a larger maze – your building has a bearing on this large maze. Students have to be made aware of this. I recently conducted a week-long workshop in IES college of Architecture where we looked at how to create land cover maps using image classification, map watersheds, and understand overlay techniques. Every college is capable of doing small electives or workshops like these where the future planners of the city are made aware of the ground realities.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award 2023, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Maitreyee Rele was a researcher and illustrator with Question of Cities when this interview was conducted. An architect by training, she spent time with Question of Cities before joining a Master’s degree course in sustainable urban planning and design in Sweden’s KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons