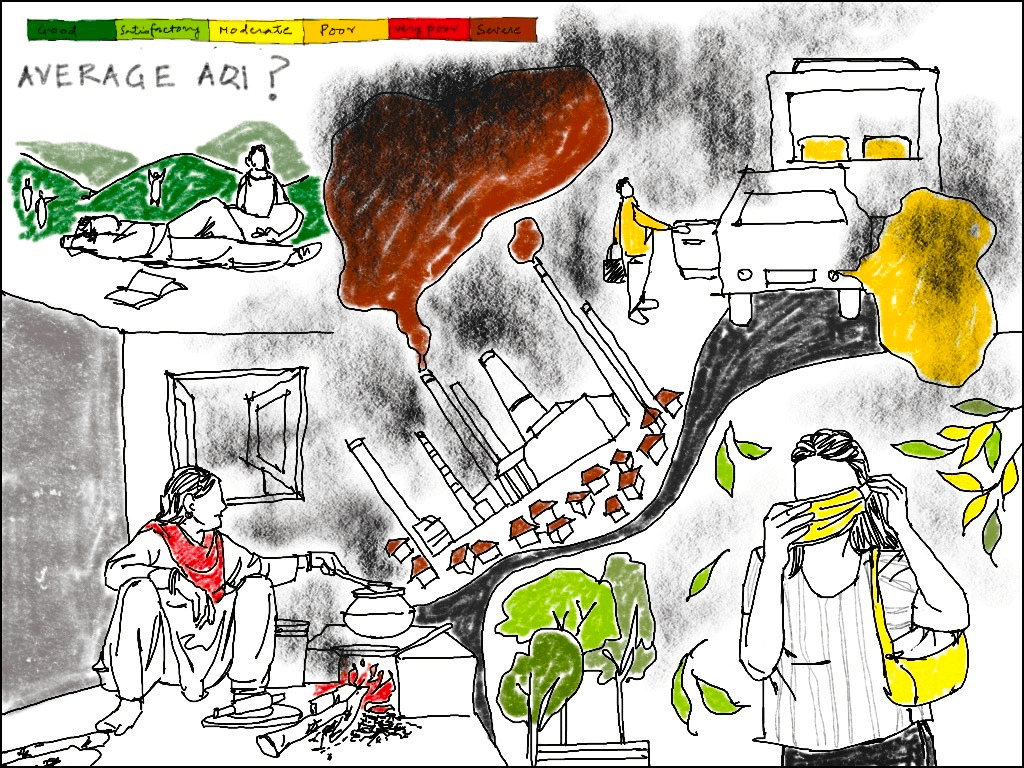

As Delhi-NCR and cities across north India grappled with hazardous air quality through November-December and people tracked Air Quality Index readings closely, often comparing one reading with another, an element that stood out is the limitation of the average reading. In Delhi or elsewhere, the average AQI, as the term goes, showed the central or typical value. Look beyond the average and it’s clear that some areas in a city had cleaner air while others suffered worse quality air than that number.

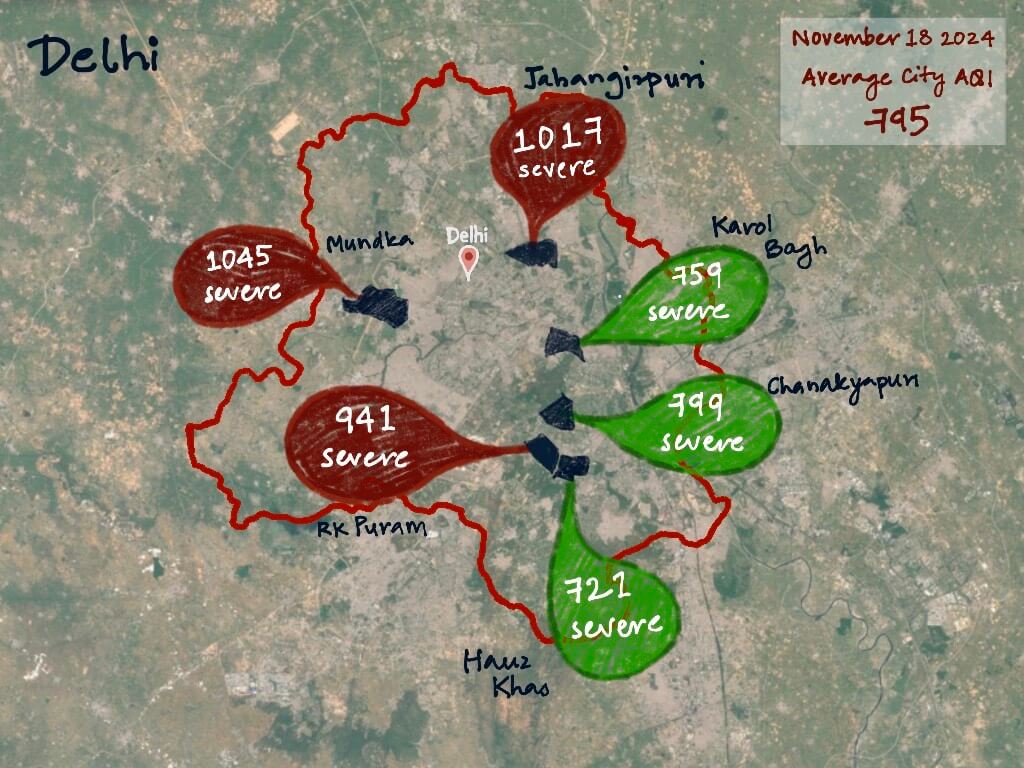

On November 18, the average AQI for India’s national capital read over 1,100 on the international platform IQAir while it peaked at 494 on India’s scale. The former is sensor-based and measured on a scale that did not have an upper limit; the latter is analyser-based and on a scale that has an upper limit of 500. Either reading led to the same interpretation: Delhi’s air was severely polluted, hazardous in the extreme. The highest was more than 200 points above the average that day in Jahangirpuri; the lowest AQI was a solid 700 points lower in Vivek Vihar. On a day when Delhi’s average AQI was 485, the monitoring stations recorded between 1300 to 1600 for Mundka, Dwarka Sector-8 and Rohini.[1] The plush Hauz Khas, though severely hazardous too, was far lower at 721.

On October 16, when the AQI in Connaught Place was 178, Anand Vihar was in the “severe” category with an AQI of 518. Whether in October or November, some areas had cleaner air than others. What this implies is that a city-level action plan, the focus of air pollution management that several cities are undertaking, may not be enough to address the issue. Differences or variation in the microclimates require different strategies and actions that are local to hyper-local.

The Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) Stage IV was pressed into implementation for the entire city of Delhi when the air pollution was at its worst but, going forward, varying levels of action in different areas might be needed to address the local readings of pollution.

Wide disparities follow locations

Like all averages, the city average flattens the peaks. Though useful, it may not be the most accurate representation of the many realities across a city. The reasons behind the wide disparities of air pollution – as also of heat or floods – could be many and complex. The highly polluted areas may be industrial zones or near high-emission industries, high-traffic and congested roads with vehicular emissions adding to the pollution load, and there may be a lower footprint of green areas and fewer trees that absorb the emissions.

Areas with commercial and industrial activities, thoroughfares and busy streets, construction sites and landfills have a significantly higher concentration of pollutants (PM2.5 and PM10) than plush residential localities with abundant open and green spaces, and wide distances between buildings. For local and hyper-local readings, the monitoring stations have to be in sufficient numbers across all types of locations in every city. Delhi has 40[2] monitoring stations; Mumbai has 25[3] across its length. Many cities in India, as per the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) data, have just one or two[4] monitoring stations – and rely on the average. Without localised monitoring which captures the variations at a granular level, pollution mitigation action will be limited.

“In general, for any city to get representative air quality numbers, the estimate is that you should have stations spread around different micro-environments as per the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) guidelines. So, fundamentally for any city with a population of around 5 million, there should be at least 10 monitoring stations placed in different micro-environments including background stations, highly polluted roadsides, residential areas, industrial zones, coastal areas (if any), etc. Then the average of all these would be a true representation of the overall picture of that particular city,” says Dr Gufran Beig, Chair Professor, NIAS and the Founder-Director of SAFAR (System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting and Research).

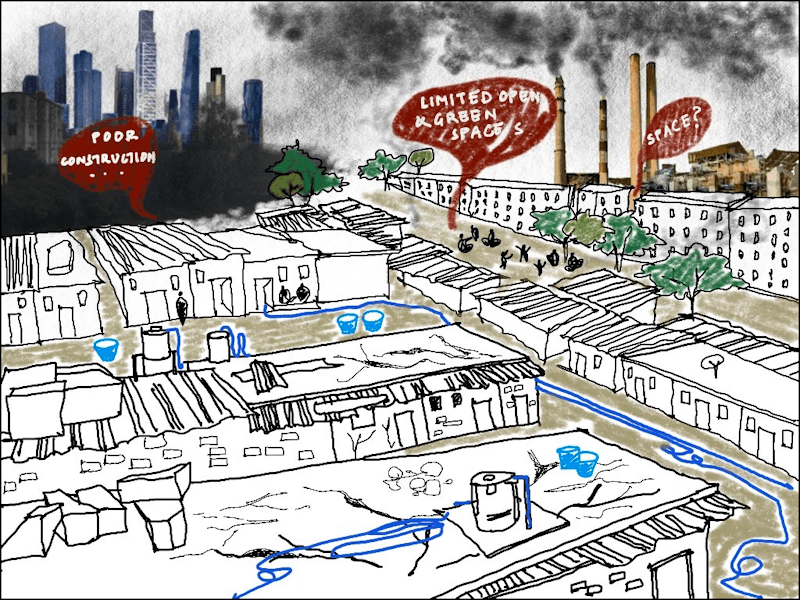

Jahangirpuri, which recorded the highest AQI, is largely a resettlement area built in the mid-1970s to settle slum dwellers from New Delhi and South Extension, and an industrial hub with factories and transport-related businesses – with few green areas or lush open spaces. The juggi jhopdis and rehabilitation colonies are cramped spaces with homes within touching distance, housing people mostly from the lower economic strata who work as vendors, construction workers, delivery personnel, security guards or domestic help. Mundka, in west Delhi, is a mixed area with residential colonies, commercial market areas, industrial areas and a large timber market.

Both Jahangirpuri and Mundka have little in common with Hauz Khas which registered lower AQI even though it was in the hazardous range. Hauz Khas, one of Delhi’s historic locations, is an affluent area with art galleries and boutiques, hip restaurants and pubs, well-manicured green areas, parks and walkways, and indoor spaces that can shut out the polluted outside air. Delhi’s average AQI treats these areas – and others – as homogenous, flattening local characteristics or causes behind air pollution.

Mumbai and Jaipur too

In the case of Mumbai, low-income neighbourhoods in Mankhurd and Govandi, also resettlement slum colonies with poor civic infrastructure, usually see higher daytime temperatures and higher AQI levels than say wealthier areas like Pali Hill, Khar and Bandra. Across the congested slums are open spaces such as mangrove forests and wetlands, but these are largely inaccessible to residents. Posh areas of Khar and Pali Hill have more accessible open areas, parks and walking tracks.[5]

November brought a sharp rise in air pollution across Mumbai but not all areas were similarly or equally affected. Residential suburbs like Kandivali remained in the “satisfactory” AQI level with an AQI of 92 while Worli and Colaba showed readings of 278 and AQI respectively; Mumbai’s average was 161. Increased and massive construction activity of both redevelopment and infrastructure as well as rising vehicular emissions in the latter areas are factors that increase pollutants. Mumbai’s AQI levels are largely also determined by the pattern of the sea breeze.[6]

Localised data becomes important in Mumbai as areas have a distinct geographical settling and proximity from the seafront. Chembur and Deonar,[7] relatively land-locked, have been recording poor air and smog with AQI of 167 and 119 respectively. These are also areas with polluting industries, a massive landfill and a Ready Mix Cement (RMC) plant in residential areas which was ordered to be shut down.[8] These are like the backyards of the city where displaced slum dwellers jostle for space between small and medium factory units, landfills, and more. The suburbs of Shivaji Nagar, Kandivali and Malad West were recently recorded as hotspots, according to a report by the Respirer Living Sciences which focused on hyperlocal data and analysis of pollution in November.[9]

“Usually, air pollution talk is about Delhi or other cities in north India but Delhi is not the threshold to compare air pollution levels. It should be the World Health Organization (WHO) standards. The narrative is that air pollution is lower in southern cities than in the northern cities but we ignore that in the southern cities too, the crisis is really bad,” says Selomi Garnaik of Greenpeace India. Its recent report, ‘Beyond North’[10] threw light on the increased NO2 levels in Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Pune, Jaipur, Kolkata, and Chennai.

All ten monitoring stations in Bengaluru recorded particulate matter (PM) values higher than the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). The annual average levels of PM2.5 are four-five times higher in seven locations and eight-nine times higher in three locations; the annual average PM10 levels are three-four times higher at seven locations and five-six times higher at five locations in the city.[11]

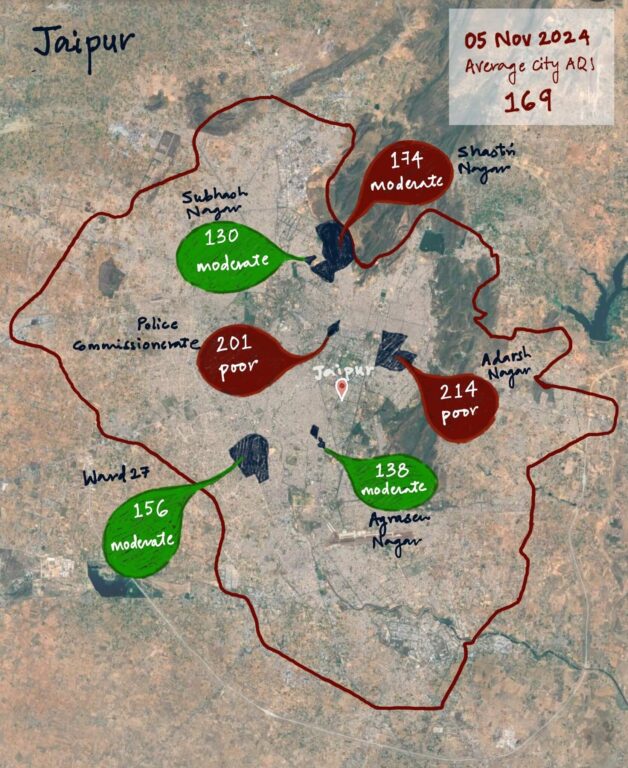

Jaipur too has been witnessing hazardous air quality; since November 18, the Pink City’s air has been of poor quality forcing restrictions such as shutting down of schools. As in other cities, vehicle emissions, construction activities, and industrial pollution have turned the air here hazardous, making it the most polluted city in Rajasthan in 2023. In mid-November this year, areas such as Mansarovar, Vaishali Nagar, and Malviya Nagar had different pollution levels from the busy Tonk Road.

While Mansarovar Sector 12 showed AQI of a healthy 69, the Police Commissionerate had an AQI of 181 while Murlipura Sector 2 showed AQI of 185; the Tonk Road witnessed AQI crossing 300. The Vishwakarma Industrial Area and the congested Mirza Ismail Road worsened the air quality.[12] A research paper[13] revealed that the levels of pollutants such as PM10 and PM2.5, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and carbon monoxide (CO) exceeded both national and international standards in some areas of Jaipur.

Inequality and air pollution

A cursory review shows that largely areas with low-income or poorer residents correlate with higher AQI levels than better-off areas. The microclimates in these areas could be the result of a number of factors that range from structural to land-use planning, zoning and materials used, auto constructed,[14] availability of green areas and open spaces that act as carbon sinks for polluted air, and other tangible and intangible elements that impact air quality.[15] These are also less serviced by Urban Local Bodies and show inadequate amenities.

However, urban development practitioner Swastik Harish is cautious about the correlation. “Everyone commuting to work or school is affected by the pollution though differently. So, we should be careful about that. The categorisation is just not about rich and poor, but also who are vulnerable, for example, children and older people,” says Harish, though he suggests that air pollution exposure is influenced by building design, lack of ventilation, cheaper materials, and low maintenance. Harish, who has been working with low-income settlements in Bengaluru’s government housing colonies, slums, and industrial areas, has seen symptoms like coughing, difficulty in breathing, lung disorders as well as cancer and tuberculosis among people.

The widely differing air pollution in the same city plays out in the inequities of health, work and incomes of people. Many in the more polluted areas are daily wagers. When anti-pollution measures are put in force, such as the ban on construction activities in Delhi, many workers are left to fend for themselves or return to their villages. Polluted air tramples on their livelihoods.

Deepali Tonk, a resident of Sundar Nagari in northwest Delhi, works as a community organiser with many NGOs in bastis. Her observation is that people underplay symptoms of pollution-related illness so that their work is not affected; they ignore the symptoms. “There is more awareness among people in bastis about their immediate environments and changing climatic conditions. However, it has become a practice for these people to not let their bodies feel what they are going through, because they have to keep working,” says Tonk. Local doctors told her that while men and children have come with throat discomfort and headaches, women have been completely absent from the picture.

Areas of Delhi like Jamia Nagar, Old Delhi, Jama Masjid, Nizamuddin and southeast Delhi, several of these with large Muslim populations, reportedly have fewer open spaces and parks.[16] Children here lack play spaces and find small areas or spaces in graveyards to play.

The correlation between pollution levels and socio-economic profiles of areas needs deeper academic research but it is clear that a city has microclimates determined by local factors, planning and zoning. As such, government action to mitigate pollution will also have to become more local – or hyperlocal.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect, illustrator and urban practitioner, works with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Illustrations: Nikeita Saraf