After Independence and Partition, India’s attempt to create a democratic polity took multiple expressions. From a semi-feudal and semi-monarchical colony, a new identity had to be forged. The ‘temples of modern India’ were rising everywhere – the big dam, the powerhouses, and the machine aesthetic-generated new language of nation building along with new institutions to consolidate the democratic frame. Scientific temper, efficiency and universal franchise were seen as the underpinnings of a democratic polity. In this context, city building took on a new meaning and the modern New India was the ideological frame for imagining new cities.

Chandigarh was born in this context but has become the symbol of India’s awkward modernisation. The city is as much a work of art as it is a living symbol of the Nehruvian project for modernity. The new nation had modernity as its goal; Modernism was the chosen language for architectural expression too. Modernism was also turning the corner in India then. The nation was already carrying a heavy baggage of obsessive ornamentalism, religious symbolism, and an Indianised version of Art Deco. Pure Modernism like Antonin Raymond’s Golconde Dormitory in Pondicherry and a few other downtown buildings in metropolitan cities had no universal appeal or impact.

The frenzy of building activity in Indian cities, and especially the making of the three new capital cities of Chandigarh, Gandhinagar, and Bhubaneswar, created an irresistible pull for many Indian architects, planners and structural engineers in Europe and the United States, studying in universities which were thought leaders in Modernism or working with various “masters of Modern Architecture”. Many of them were drawn to the opportunities in India. Many might have also been inspired by the nationalist spirit of building a progressive, modern nation. The then Indian leadership accepted them with open arms to partake in the nation building project.

The time was ripe for a fusion of western Modernism with the need to symbolise and represent the hitherto unknown typologies of institutions. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was leading this thought process. The dichotomous ideologies of Gandhi and Nehru and the many letters exchanged between them for the choice for India’s development directions further sharpened Nehru’s choices towards a Fabian socialism against Gandhi’s village-centric India. After Gandhi’s death, the path taken was unbridled Modernism. Cotton politics was at the centre of this dialogue and industry-based modernisation took centre-stage discarding rural mud for urban concrete. The events in Ahmedabad and the setting up of five contemporary institutions in education, science and management needs to be understood within this discourse.

The collective client power of the central government and India’s industrial elite also attracted considerable interest in star architects of the world of the time. The arrival of Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn, Otto Koenigsberger, Joseph A Stein, and Albert Meyer in India was highly consequential to the subsequent development of India’s Modernism in architecture. An army of Indian architects with their Modernist ideology ruled the narrative. Designing new cities, campuses and buildings became the vehicle of modernisation.

Confluence of histories

Chandigarh represents the manifestations of Modernism and is the confluence of many micro-histories. Various trajectories converge to give new form to Time and Space. Without opening the larger discourse on the choice of Le Corbusier as the urban designer-architect for the project, it will suffice to state that a man whose dreams were to build a skyscraper city where helicopters would hop from rooftop to rooftop, finally dreamt a glorified suburbia as the final form for the only city he was to build. For his progressive European mind, the grid-iron form of Greek cities was an obvious choice. There is no indication that he visited Pondicherry, the grid-iron city claimed by the French (in other versions conjured up by the Dutch and the possibility of a grid-iron Vedic Pathshala based on the Agamas also exists) or even the 17th century grid-iron city of Jaipur in Prastara form.

The minor confusions between Greek’s direct democracy and India’s electoral democracy notwithstanding, an open grid that provides universal access to all parts of the city for all citizens found favour for the new city that was to be Chandigarh. The choice of open flat land at the base of the Himalayas was clever from the ease of development perspective. Le Corbusier developed a well-integrated functional city plan on top of this wide open land, with a hierarchy of road networks, functional disposition driven by zoning, hierarchy of open spaces, and classical neighbourhood roads.

Unfortunately, plotting and density distribution strategies failed to create the universally-accessed equitable city that in the Nehruvian vision would have heralded India’s democratic future. Access is also a function of economic and social factors in the complex Indian economic structure and over time human activity emerges a much stronger force to reckon with than the design intent located in a one-dimensional understanding of citizenship.

Archetype of exclusion

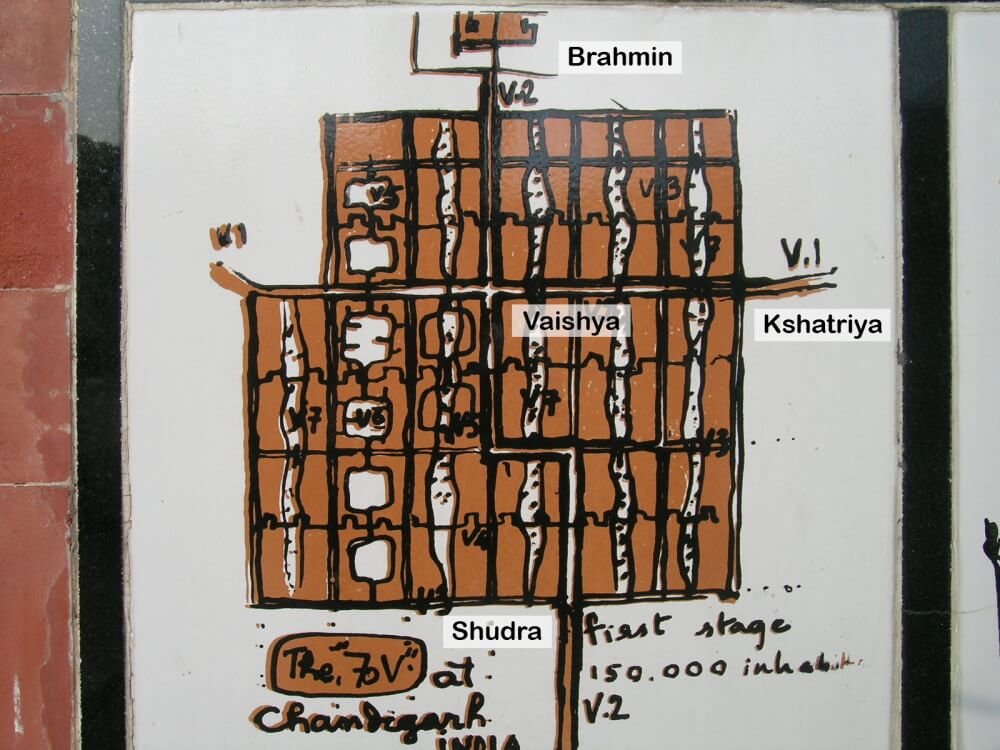

Embedded in its grid-iron and universal access of movement networks, the Chandigarh plan has inherent in it an uncanny semblance to the social hierarchies of Varnashrama (division of Hindu society into four hierarchical groups). In this, the ‘new Brahmins’ (administrators) occupy the rising land in the north which has the concentration of administrative structures and proximate housing for the powerful and the wealthy, while ‘lesser citizens’ occupy the southern sectors with higher density housing.

The main commercial functions as embodied in the central business district (CBD) are in the middle, in Sector 17, representing trade in the middle of the anthropomorphic form. The industrial functions, employment centres of the labour, and other appended functions like the railway station are across the middle stretching out like the arms from the east to west.

Photo: KT Ravindran

A clear class hierarchy is entrenched in the city from north to south; much like the Varnashrama hierarchy from Brahmins at the head to the smaller plotted and high-density housing of lower-rung government employees at the feet. However, as the city moves towards the south, public areas become more vibrant and markets leapfrog across the sectoral boundaries – smaller plots, smaller buying capacity, higher densities and defying the grid to generate interconnected links across sectors that are divided by arterial roads characterise Chandigarh.

This drives home the hollowness of the classical neighbourhood format of the sectors, serviced by commerce and primary schools located in its core. Life is turned inwards where the man commutes to work by car to a different world view about the public.

‘Infected’ by Life

The anthropomorphic imagination in the Chandigarh plan is not unlike the “Vastu Purusha Mandala” (a metaphysical plan that guides design and construction of structures) with head, belly, arms and the feet. However, unlike the Agamas and Vastushastra, Chandigarh fails to build up the flesh and body of the city by using building typologies. Varying plotting sizes and the modernist setbacks-based city development in the entire city, mixed with confusion about inbuilt values of suburbia robs Chandigarh of its potential urbanity.

An orthogonal street network fit for efficient automobile movement also ignores the street picture at the cost of the city’s image. Wide roads and expansive roundabout at intersections isolate the lived experience of the city from the potential intimacy a designed structure could have provided. A monotonous public experience is animated only by people’s mediation in occasional nodes. The city, in other words, bypasses the public experience – one can travel across Chandigarh without encountering the city that one is actually inhabiting.

The “eventlessness” of Chandigarh is, however, has a counterpoint in the imminence of popular public imagination. The wide streets, green landscape and the overwhelming presence of order has forced popular imagination to invent the antithesis of gravity of the orderly city. Consequently, the relatively anarchic and amorphous Nek Chand Garden has emerged as the most popular public space in Chandigarh. The water body and the landscape around it have to scream in the midst of a silent prayer and create a rural mela.

Photo: KT Ravindran

This garden complex has generated a popular public space with colourful boats, bazaars, fun and games. Le Corbusier’s artworks and product design are sold in an informal market as souvenirs, creating a curious mixture of rural Punjab and high Modernist artefacts. The ironic positioning of these counterpoints is at once amusing and intriguing. However well controlled by design intent and bylaws, the rural interface as an irresistible force will impact even the most celebrated examples of modern urban design when it is imposed from above. Chandigarh lives these contradictions while its youth is longing for Delhi.

The fissures

The city of order reflects in multiple ways as women stay back at home with domestic chores and men commute to work in business attire – an urban stereotype perpetuated by the western suburbia that not only consolidates the patriarchal mindset but also perpetuates the role-playing of men and women immersed in domesticity. For pensioners and rent-dependent complacent families, this is certainly ideal but this is certainly to be challenged in the future, if not already rejected, by the growing number of double-income families with greater job mobility and high social aspirations.

In the recent past, two major fissures in the structures of Chandigarh have split it wide open:

A) A strictly controlled land use, urban form and functional structure has ensured that poor migrants are not let into the pristine urban structure to prevent it from being “defiled”, creating high concentrations of slum clusters to develop in the immediate peripheries and along highways leading to the city.

B) The European orderly urban form along with the million moves that ordinary people make every day to negotiate the modernist spaces at home, in the neighbourhood and in public places, as well as the presence of the Nek Chand Garden along with inhabitation of the lake areas need to be viewed as rural Punjab appropriating the design of the preserved city.

Contrasting lifestyles, tastes, and patterns of public habitations of the Indian city are often seen as chaos as opposed to order and the predictable regularities of a well-planned city. Herein lies a lesson in life that violative reaction to order is indeed a sign of life in the Indian city which owes its essence to the vibrant every day.

Power of image

Along with Gandhinagar and Bhubaneswar both designed by the German architect Otto Koenigsberger, Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh was the third capital to come up in democratic India, all more or less following modern planning logic, wide orthogonal streets, and a crowning Capitol Complex. These capital complexes contain the three pillars of democracy: The Legislature, Secretariat, and Judiciary. These three functions are distributed in a spatial order that represent the collective power of institutions in a democracy. In a way, the imperial capital of New Delhi already demonstrates this positionality of power in a polity, albeit from an imposing and colonial worldview.

The socialism that India chose to follow after Independence and Nehru’s seminal role in expressing modernity as the vehicle to build a strong industrialised, democratic India forms the main conceptual frame for all the capital cities designed within the new federal structure of the country. Subsequently many states were created, or later subdivided, with each of them getting a new capital. Yet, Chandigarh remains a singular replicable icon that has dominated India’s city planning. Le Corbusier’s choice of siting the Capitol Complex at the base of picturesque mountain on the highest portion of the city’s body has multiple implications in Chandigarh’s morphology. It also implies some far-reaching insights into the history of democracy in India. Only that clarity emerges now, after years of historic distance in time as well as India’s appropriation of the process of democracy.

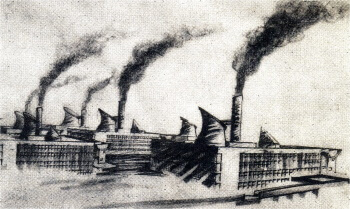

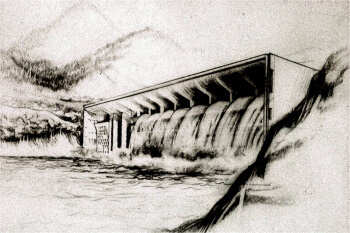

It is pertinent to point out that Nehru had clear ideas about Indianizing modernity though no evidence exists that he communicated this to Le Corbusier. On his own, Le Corbusier as a sensitive architect, set upon journeys recording various locally present forms to trigger his design initiatives and finally narrowed them down to the “temples of modern India” as famously described by Nehru. These are the powerhouse, the big dam, and the factory (machine aesthetic).

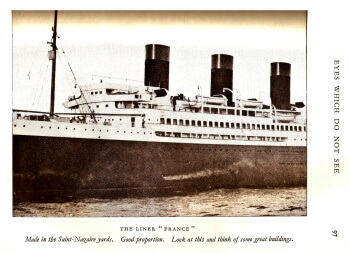

Le Corbusier also brought in to play his long-standing obsessions with the beauty of a steam ship to epitomise the ultimate functionality, form, purity of a perfect machine without flab or ornamentation. The result is his fertile and highly creative imagination conjuring up the pillars of democracy as an iconic imagery of a progressive mechanistic new India: A western style democratic, industrialised, and rational nation with scientific temper.

Multiple truths

The stunning architecture that Le Corbusier produced in seductive brutalism at once evoked multiple aspirations of the new nation. It now enjoys the UNESCO World Heritage status. The composition of the capital with the mountains at the back and his attempts to integrate public art into the landscape remains, as yet, unsurpassed in India after seven decades of nation building.

Multiple truths emerge when you approach the city through multiple trajectories. From the historic lens of lived lives in Chandigarh city, from the perspective of the capital serving two state governments (Punjab and Haryana) to histories of Punjab’s separatist movements, and the growth of collective insecurities in its body politic, the capital which is meant to represent people’s power has now become isolated like a fortress in war. Barbed wires and gun toting policemen dominate the well-designed concrete landscape. Bureaucratic permissions and high-security motorcades separate the public from their rulers. And the location, isolation, and inaccessibility built into the plan of Chandigarh has now brought it closer to the Acropolis placed on a mountain.

This is not to blame the design for the distortions in the functioning of democracy in India. Chandigarh is a clean city, even after decades of habitation which provides legitimacy to its original design intent. From an integrated worldview, the political process and history of power struggles that have maltreated democracy and its prime vehicle -modernity in India – can be now read through the morphological distortions in Chandigarh, as if the DNA of the city contained this potential schizoid condition that separated people from their own power in a democracy.

Chandigarh remains an icon not only in its seductive physical presence but also as a prophecy of the future of democracy in India.

KT Ravindran, veteran architect, was Dean at the RICS School of Built Environment, Professor and Head of Urban Design at the School of Planning and Architecture in New Delhi, and the Founder President of the Institute of Urban Designers. He has served on government committees, including the one to build a new capital for Andhra Pradesh, and several national and international juries. He has been an advisory board member of the United Nations Capital Master Plan, chairperson of the Delhi Urban Art Commission, and a trustee of the Indian Heritage Cities Network Foundation besides being associated with INTACH. Prof Ravindran works in the public decision-making sphere, addressing the environmental sustainability of national-scale architectural projects and advocates involving local people in redesigning their space.

Cover photo: Raakesh Blokha/ Creative Commons

There is 1 comment

Very interesting and informative article.