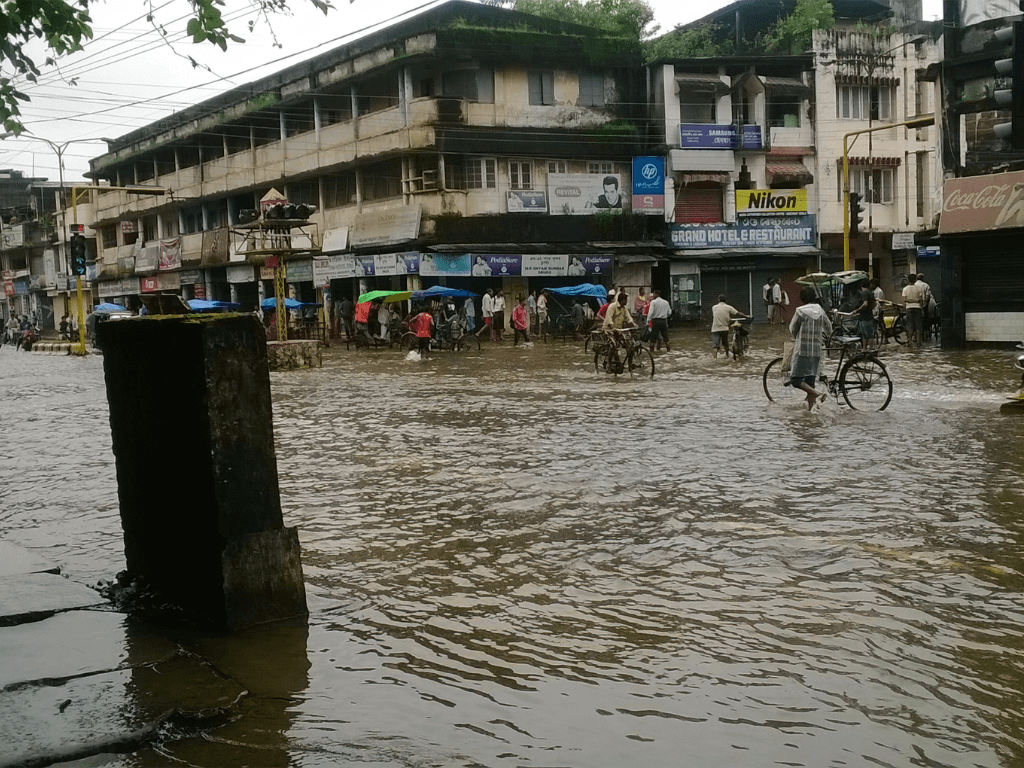

The southwest monsoon hit the country more or less on schedule in June. As if on cue, reports began pouring in from cities and towns across India about micro to massive flooding. Besides the usual suspects of Mumbai and Chennai where areas flooded within an hour or two of a downpour, videos and photographs of gushing water and landslides came in from Gurugram in Haryana, Mandi and Kullu in Himachal Pradesh, towns in Uttarkashi, and almost all districts of Assam which have been the worst hit in recent memory.

If it rains, it will flood and cause devastation all around – this seems to be the default setting of urban governance in India now. Floods are no longer rare natural occurrences which disrupt city life once in a while. Instead, given that the frequency and intensity of floods in cities have increased, they are now considered as ‘disasters’, flood management is a growing sector of study and financing, and no climate action plan is considered complete without space and thought given to flood mitigation and adaptation measures. The loss of lives and damage to property and livelihoods have increased substantially in the last few years.

City administrations and state governments, at best, try mitigation measures – installing pumps in low-lying areas, desilting and cleaning storm water drains, preparing rescue boats. When all of it fails, they issue advisories to people to stay indoors so that lives are saved. Yet, in the last decade, nearly 15,400 people lost their lives and lakhs were displaced across India. Floods caused the maximum harm of all the natural disasters in India from 2011 to 2020, accounting for 67.2 per cent of the total deaths caused by natural disasters – nearly twice that it used to be, 20-35 per cent, in the previous decade.[1]

The approach to addressing floods has mostly been mitigation measures, some of which are essential to save lives and property but in focussing on the short-term, small-scale and disparate mitigation measures – to be safe here and now – governments and multiple urban agencies have been missing a key piece in the complex jigsaw of urban flooding: Ecological destruction and the need to factor ecology in flood management. Floods in cities are human-made disasters too.

Where will the water go?

As cities expanded, driven by economic impulses and the need for constructed spaces increased, its natural areas – green and blue – were encroached upon. Forests and groves were razed, green areas and open spaces shrank. Water bodies, watercourses, wetlands and other elements of their natural drainage systems were damaged or entirely lost. The stormwater drainage built into the under-bowels of a city proved inadequate over time. And, due to Climate Change, the pattern of rainfall changed to drop more rain in fewer hours. The water has no space to flow out or seep into the ground.

Hence, flood management which does not address the existing ecological devastation and, subsequently, build ecological repair and conservation into its action plan is only scratching the surface without going to the core. Just as cities built in an ecologically unsound manner are designed to flood, flood management measures which leave out ecological conservation are designed to fail.

Photo: Creative Commons

Ecological concerns are being slowly recognised. The 15th Finance Commission stated in its report that flood management “requires an approach that brings together urban planning, ecological conservation, and disaster management. The state government needs to support a set of interventions that are implemented by multiple urban agencies working together.” It would have been unlikely to see the words “ecological conservation” in a Finance Commission report years ago. It recently allocated Rs 3,000 crore to seven cities over the next five years to undertake targeted flood management measures.[2]

Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad and Pune are the chosen cities but with Mumbai and Pune getting Rs 100 crore and Rs 50 crore respectively this year, it is a no-brainer on what work will be done. Floods have been lately addressed as ‘disasters’ by governments and the National Disaster Management Authority. India’s central government now considers urban floods a national issue but one city does not flood like another. Urban floods are local, even hyperlocal, events with the ecology and topography playing major roles in determining the flood frequency and intensity.

The ecological aspect, first flagged off by conservationists and citizens’ groups as nature-based solutions to tackle floods in cities, is gradually making its way into reports and recommendations by top-notch international business and finance consulting firms. This is welcome so long as it does not become merely the flavour of the season, as it were. They are supposed to be socio-ecologically sound and flexible enough to be adopted by individuals, communities and areas in a city, and for the entire city by government agencies too.

Nature-based solutions include, but are not limited to, setting up urban forests and practising urban farming, generating terraces and slopes, creating open spaces and green spaces for the water to soak, making more permeable surfaces along roads and buildings, promoting rainwater harvesting, restoring river floodplains, protecting and rejuvenating wetlands, restoring natural drainage network and so on. Nature-based solutions, sometimes called nature-based infrastructure, is the green-blue infrastructure – distinct from and opposite of the grey infrastructure of constructed spaces and built environment in cities.

Photo: Ramnath Bhat/ Flickr

From green-blue to grey, and back again

Cities were built on land cleared of green spaces or by landfilling blue areas, inaccurately called ‘reclamation’. These reduced the area available for rain water to seep into the ground or for it to flow along natural water channels; as more and more surface area was constructed upon, the holding area for water reduced which increased the runoff from rainwater and stormwater. All cities which rapidly expanded in the last few years show this. Bengaluru is a befitting example.

Located in the watershed region of two rivers and valleys, the ‘garden city’ had an interconnected natural layout of lakes and other water bodies which formed its natural drainage system. In this, the primary canals, called Rajakaluves, linked hundreds of lakes in a complex web and collected the runoff through other channels to discharge it into the lakes. In the 1980s, there were more than 280 lakes in 161 square kilometres of the city – ample space to hold the rain water.

The expansion of Bengaluru in the last 25-30 years, driven by the IT and IT-enabled services, turned the languid city into a vibrant economic hub. By the mid-90s, it had expanded to 226 square kilometres and then to 741 square kilometres by 2011. However, as its built area exponentially increased, the share of dense vegetation cover declined from 68.27 per cent in 1973 to less than 15 per cent by 2013. As many as half of the city’s storm water drainage infrastructure deteriorated in length, according to data from the Indian Institute of Science analysed by the real estate research firm Knight Frank.[3]

“The surge in infrastructure and real estate development to accommodate the population growth and the associated increase in land surface properties has interrupted the natural valley system of Bengaluru and damaged the interconnectivity of the lakes within the city. Additionally, at a few places the primary stormwater drains connecting the lakes are old and decayed due to non-maintenance and have lost the capacity to withstand water runoff in case of heavy rainfall,” the Knight Frank report pointed out.

The impact of this encroachment on green and blue areas was exacerbated by changing weather patterns and extreme rain events. Shorter periods of rainfall but intense heavy rain in a few hours in a city in which the carrying capacity of water was severely reduced was a perfect recipe for floods and waterlogging, as happened last year.[4]

Complex factors may coalesce at once to lead to severe flooding but the root causes usually lie in the disturbance or disruption of the natural drainage network and destruction of green spaces. Returning from grey infrastructure – built environment or constructed spaces – to green and blue infrastructure after initially destroying it to build the grey is a supreme irony, nature would say if it could. This return may not be ideal yet, but small efforts towards restoring and conserving the natural areas and water bodies are steps in the right direction.

Photo: Thejas/ Flickr

Same template, similar floods

Bengaluru is not the only city to have sacrificed its natural drainage or green spaces in the name of urban development. Gurugram is a classic case of a modern city with gleaming high-rise towers linked by roads, inundated after even a light rainfall. Floods are a nightmarish ritual several times a year in the city that could have been planned and designed to handle climate events better. The link between its flooding and the shrinking of its water bodies is there to be seen – and set right.

There has been a staggering decline of 42.5 per cent in Mumbai’s green cover in the last 30 years and the area lost is more than the size of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, according to a study published in peer-reviewed journal Springer Nature.[5] Similarly, its four rivers have been heavily encroached upon, the restoration of Mithi river after the 2005 flood is not yet complete, the network of hundreds of kilometres of nullahs has been snapped by construction projects, wetlands gradually diminished, and its storm water drainage network far from capable of handling a heavy rain event.

In New Delhi, which routinely floods, the Akshardham Temple Complex and Commonwealth Games Village (CWG) were constructed on Yamuna’s floodplain leaving little space for the river to swell. Guwahati witnessed its natural water channels, the Deepor Beel and Silkaso Beel, choke with construction; Assam registered the highest share of the national tree cover loss from 2000 to 2020. In Chennai, the second runway of its airport was built over the Adyar river and the airport on the river’s floodplain. As the city’s built area increased three-fold between 1991 and 2021, its vegetation cover declined to 17 per cent and the area of its water bodies from 8 per cent to 4 per cent, according to the draft City Climate Action Plan.[6]

Game changer: Plan with nature

In these cities and others too, urban development, or the rampant construction that goes in its name, left no space for rain water to soak into the ground or flow out. Even accounting for Climate Change impact on rainfall, poor urban planning is primarily to blame for urban floods. It is evident that this model of constructing a city has turned self-sabotaging and unsustainable.

So what can cities do? Rudely awakened, cities have been adopting flood mitigation measures and, egged on by international consultants, deliberating on long-term adaptation strategies. Coastal cities have not only flood but also possible submergence to worry about, going by the spate of studies and projections by climate scientists. Discussions about flood management revolve around financial prudence. As Dr Kapil Gupta, professor in the Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, said in this interview.[7]

“The amount of investment is generally a fraction of the total damages. International studies have shown that the investment needed, in terms of following building by-laws, constructing proper infrastructure, establishing and enforcing mitigation measures, is only about seven per cent of the total cost of damage that would have occurred if the above measures were not put in place.”

However, the game changer is planning and designing cities with nature. As a concept, it has been around for decades – among others, Sir Patrick Geddes recommended it in the early 20th century and Scottish architect Ian McHarg wrote the book Design with Nature in 1969 – but the need to adopt it as the default way to plan cities has never been more urgent. Others have engaged with the idea but the simple and powerful explanation came from McHarg.

By “design with nature” McHarg meant that the most recommended way for people to occupy and modify the earth is to plan and design with regard to both the ecology and the character of the landscape. “In this way, he argued that our cities, industries and farms could avoid major natural hazards and become truly regenerative. More deeply, McHarg believed that by living with rather than against the more powerful forces and flows of the landscape, communities would gain a stronger sense of place and identity,” explains this note by The McHarg Center.[8]

To plan and build with nature is not only sustainable and ethical, it is absolutely the need of the hour.

Cover photo: A flooded road in Dibrugarh, Assam. Credit: Creative Commons