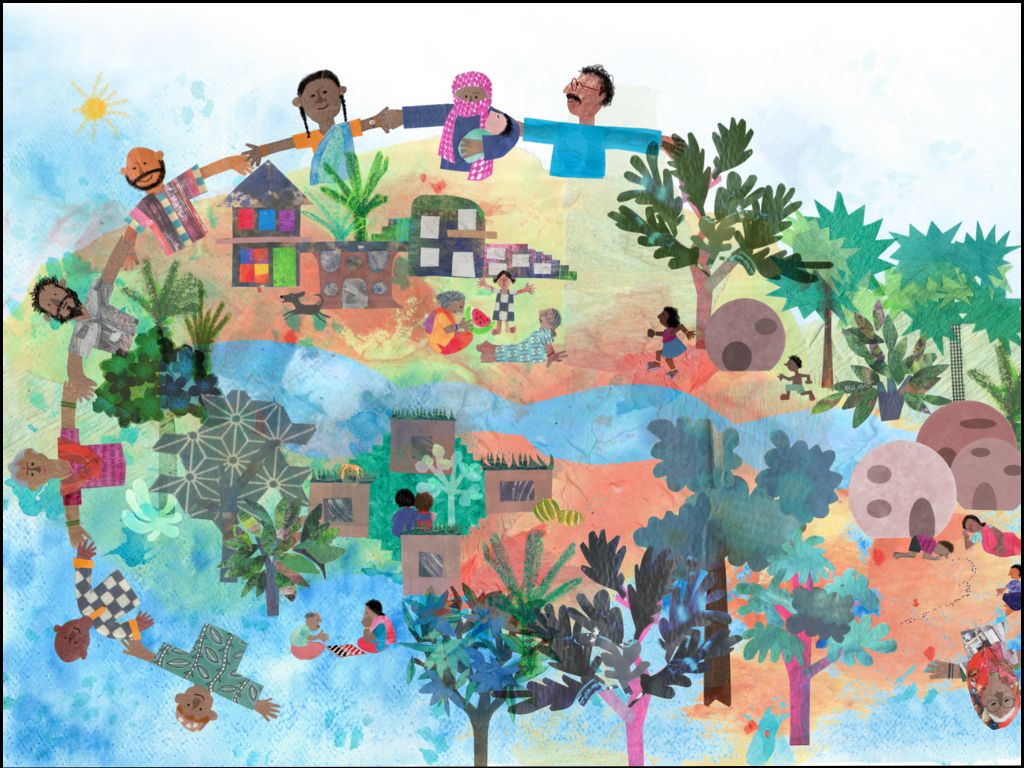

When children imagine their city, they come up with unbiased ideas, out-of-the box suggestions, for happy and inclusive cities. “A city is not judged by its architecture, by the wealth it creates; but, by how people come together to share their lives and experiences,” says Deepa Balsavar, whose illustrations for Happiness City, written by architect, writer and researcher Bhawna Jaimini, are lively and evocative.

The book opens discussions for an ideal city as “city planners forgot that the width of a street needs to accommodate a dog’s siesta, a hawker’s cart, and a child’s hopscotch boxes inscribed on a stick on a warm mud that is gentle on their knees” and shows what a city imagined and created by children might be. Such a city might seem like utopia but Happiness City assures that it is, indeed, possible. Jaimini and Balsavar spoke to Question of Cities about the book and giving young minds a creative space.

Photo: The People Place Project

What was the idea behind the book?

Bhawna: Initially, it was not supposed to be a book. I wrote it because a group of people were reaching out in the pandemic to write on different disciplines such as food, architecture, environment. The idea was to write a manifesto on how we can think of a different world, especially during the pandemic. So, I explored how happiness can guide us into thinking about cities which are inclusive, which are not extractive, transactional, basically all that they are now.t.

This became a long manifesto-ish poem. I sat with it for almost a year, then met Nisha (Nair Gupta) who heads the People Place Project. When we were discussing book ideas, I showed her this. I imagined it as a series of images. Nisha saw potential in this as a book. Obviously, the form had to be edited and it took us almost seven months to find an illustrator. Somebody suggested Deepa. We were very excited, we sent the poem to her and she agreed.

Deepa: I just loved the idea of the poem. It was long and, at first, I didn’t feel that this was a poem for children. But then I realised it’s not an alien concept to them, children would embrace it far more easily than most adults. So, while it’s written in an adult style, I felt it straddles an age divide and that we should make it a joyful book for children and adults.

I loved Bhawna’s and Nisha’s ideas. We did a lot of work together. For instance, the idea of the hands. Bhawna, Nisha and Nisha’s daughter came home one day, we traced their hands and they coloured it with crayons. We ‘felt’ the book, it emerged from the team. All of us had a role to play and there was a fair amount of feedback on what it should show, what the images are. There would be papers and crayons. Crayons because the book itself talks about creating a city with crayons. It was joyful to do.

Happiness City has imaginations, interpretations, and emotions too. What are your ideas of a happy city?

Deepa: I think a happy city is one that puts all of its citizens foremost. A city is not judged by its architecture or the wealth it creates but is a place in which people come together to share their lives and experiences. I remember I attended a talk a long time ago in which an architect said that once you start having gated colonies in Mumbai that will be the death of Mumbai. Once you start separating places into ‘them’ and ‘us’, it creates divisions and mistrust.

Instead of pouring money into being exclusive, our cities should be putting money into shared spaces where people can come together, celebrate cooperativeness and kindness, and have common spaces to know one another. For me, a happy city is one which takes this into consideration and also thinks of migrants. We keep talking about Mumbai being overcrowded but almost everybody who lives here came for a better life. Surely, all of them have a right to this city. Every child does. Every human being has the right to work, to safe drinking water and healthcare services, to be secure. This is not utopia. These should be the priorities of any city. This is what constitutes a happy city. We shouldn’t have to see cooperation and love only in crises such as the flood in Mumbai. If that spirit exists, it should exist at all times and be at the forefront. That’s a happy city.

Bhawna: For me, a happy city is where joy is not a commodity and everyone has a right to it. The book also talks about how the language of privilege has also changed. If you have a structurally safe house and if you look out a window and you see a tree in Mumbai — I’m not even talking about a sea view — you are privileged. The book also has come from my work in Govandi, where I worked closely with the community for five years. The other is my own upbringing in Delhi where I grew up in an urban village. It was a close-knit community, not having access to any open space. So, I think it was also a response to all that.

Why are simple things not accessible to everyone? It does not cost a lot of money. First, have better footpaths, trees, and housing. It’s not that we are a poor nation and can’t afford them. Just a fraction of the money spent on mega projects can make a difference. Everyone who lives in Mumbai has a right to basic things like everyday joy which comes from being able to walk properly, breathe clean air, let your kids run on streets without fear. So, I think it’s not a novel concept, it’s basic. Happiness is an emotion that ties everyone together. It’s easy for people to think about cities, planning and development through that angle.

The book makes a reader feel a sense of ownership of the city. How can it make children imagine their cities?

Bhawna: I didn’t want to write for architecture or planning or activist audiences. I was thinking of themes that everybody could relate to. Themes like access to green spaces, access to housing, urban environment not as a place which exploits but nurturing. It was always meant to be something that can be used to have dialogue. The themes are essentially which can start a dialogue without making it too complex.

Deepa: Of course, Bhawna’s words were the heart and soul of it. I needed to find a way to not only interpret what she was saying but take it a little further which came from my own experiences. When we speak about ordinary people, those who have no assets and yet work the maximum hours, I see them around me – men, women, children, band master in his uniform, all real people around us. It’s only when you draw from your experiences and the real world that you get authenticity.

I asked children what sort of house they would like to make. Something out of a rail carriage or a treehouse, they said. A little girl from a slightly more urbanised setting said she wanted one of those round houses referring to The Hobbit. Earth housing has been a part of our architecture where mud, clay and straw have been used, and that is what I incorporated into the illustrations. I wanted to give children a lot to think about, explore, see on every page. One of the visuals is of a woman mechanic and behind her is a woman, belt around her waist, doing plumbing. This idea came from a story in Rajasthan where women were trained to do plumbing in a cluster of villages because men had migrated to cities.

The book is meant for children but surely adults can take away lessons too.

Bhawna: Our childhood was different from what children have these days, that of our parents too. They remember a time when our cities and spaces were not so commodified. I remember the streets being used for weddings and other gatherings. Now, you pay for a venue. The concept of making houses for each other is not a novel concept. I saw it in Spiti while doing a project. I met a woman whose house was under construction. She had a register. She was keeping account of people coming and helping her so that when their house was being built, she would help.

Deepa: I come from an earlier generation and I remember a very different Mumbai — friendly, safer, cooperative. I was among the privileged and I was made aware of that privilege. Somewhere along the way, as adults, we became jaded in our ability to dream and think. I’m hoping this book will allow parents to talk to children, to think differently, beyond lip-service to the environment, global warming. Most middle-class parents and people I know rarely incorporate these ideas into how we live, how we affect the lives of people around us, the globe or the climate. I’m hoping that the book will generate some sort of a discussion. The book is meant to provoke, raise questions. It’s not a blueprint.

I’m hoping that this adult-child book will help create a platform for discussion but even if children feel excited about the notions and start talking, then it will somehow embed itself in their minds to crop up in different ways later. For instance, Nani’s walk to the park also has the community as the centre of the book. When Nani takes her grandson for a walk, he finds that she has renamed all the roads to reflect values important to her — so, there’s the lane of friendship, the lane of love, and the lane of dreams.

When I first did a workshop on the book with children, they came to me saying, ‘we’re going to rename all the roads in our locality after the things that are important to us’. The fact that they were excited, realised that they could take ownership, that they could somehow put their imprint on their surroundings, shows that there’s nothing stopping us from reclaiming the areas and making them special. I am hoping that will happen, if not now, two or five years from now. Children will remember and say things are possible.

The visuals depict a diversity and harmony that we seldom see. How can the ideas be translated to reality?

Bhawna: I think it’s a way to ignite dialogue, spark conversations, because kids are receptive. Both Deepa and I have been doing workshops with the book. We ask children to imagine a city without money, they don’t say ‘what are you talking about?’ They instantly start thinking. Because they don’t have pre-considered notions and biases, they get the concepts very easily. We’ve had some really great discussions. All we can hope is that it stays with them. Cities are always places of hope.

What would a city designed by children look like? Were the illustrations based on this imagination?

Bhawna: Children still haven’t othered people. The idea of coming together flows easily. Get five children together, they will invariably start playing together. It is easy to evoke empathy in children. You can have a conversation about space for animals. I used to think that it was easy with adults. I did my master’s last year and we had a session on animals’ right to the city. There were some really staunch people who said that animals do not belong in the city. I was stunned. We have done 7-8 workshops with children and this has not happened. So I think that equity, equality, comes naturally to children.

Deepa: Children have a natural sense of justice. We underestimate children’s power to reason and to decide for themselves what they want. We are busy making decisions for children. We are busy pussyfooting around each other, thinking about whom we are going to upset, what will be politically correct, or what is going to harm our growth up the career ladder whereas children are able to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Happiness City gives importance to common spaces, your phrase ‘a city for nobody, but for everyone’ stayed with us. What is the importance of common spaces for children?

Bhawna: I would like to give an example. We were testing certain concepts from the book. I was conducting a city-making workshop at a children’s festival in Bandra. I asked the 12 children present to draw spaces where they find happiness. An eight-or-nine-year-old drew Prada and Gucci showrooms. It really puzzled me. I talked to them about khadi and handwoven fabric but the kid was very adamant. After 10 minutes of back-and-forth, he says ‘fine, you can have a Fab India’. I then realised that even with enormous privilege, how isolated this child is, Money gives you access but it gives you access of only one kind.

Common spaces where you meet others who are not your classmates or not from your socio-economic background, are important for kids to learn empathy, learn about the world. We grow when we are questioned and challenged, when our world’s views are put to test. This won’t happen in classrooms, malls, or amusement parks. This happens in spaces where experiences are not curated.

Deepa: Cities are magical spaces. Why is the local train so romanticised in cinemas, in books? Because it is where you meet people of all kinds. You develop a familiarity, friendship, sometimes even without talking. Those faces are important, especially for children. We get into this habit of thinking nature is outside the city, it is for villages and that cities are meant for working and earning money. When you introduce ideas about why can’t we have a city where we see fireflies, where we can lie down on a bench and look up at the night sky, a city with green, where you can walk through pathways rather than roads, children look in wonderment and agree.

The theme of care is central to the book. How can our cities become more caring?

Bhawna: Like Deepa said, our cities have become bedrock of carelessness. However, we can start with treating spaces of care and the care workers with more respect and dignity. Just look at the state of anganwadis and the thousands of women who toil away everyday and are not even treated as workers with a right to basic living wage. ASHA workers who were at the front and centre of our pandemic response are constantly struggling for very basic demands. Our cities will become caring when we start taking the work of care seriously.

How does one reach urban concepts to children?

Bhawna: Children get it. I would like to bring in a dear friend and colleague, Ruchi Varma, who works in Delhi and has done this fabulous project on school streets. They worked with a group of kids for almost five years and they realised just how insightful the children were, how deeply they were thinking and how unbiased their minds are.

I don’t think we need to craft a different language. We need to understand their experiences better. They understand the urban environments much better than a lot of people. What we need to do is we just need to create a space for them. Conversations of children in the city get relegated to child-friendly spaces but children are everywhere.

Illustrations by Deepa Balsavar from Happiness City, published by People Place Project, reproduced here with consent.