There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.

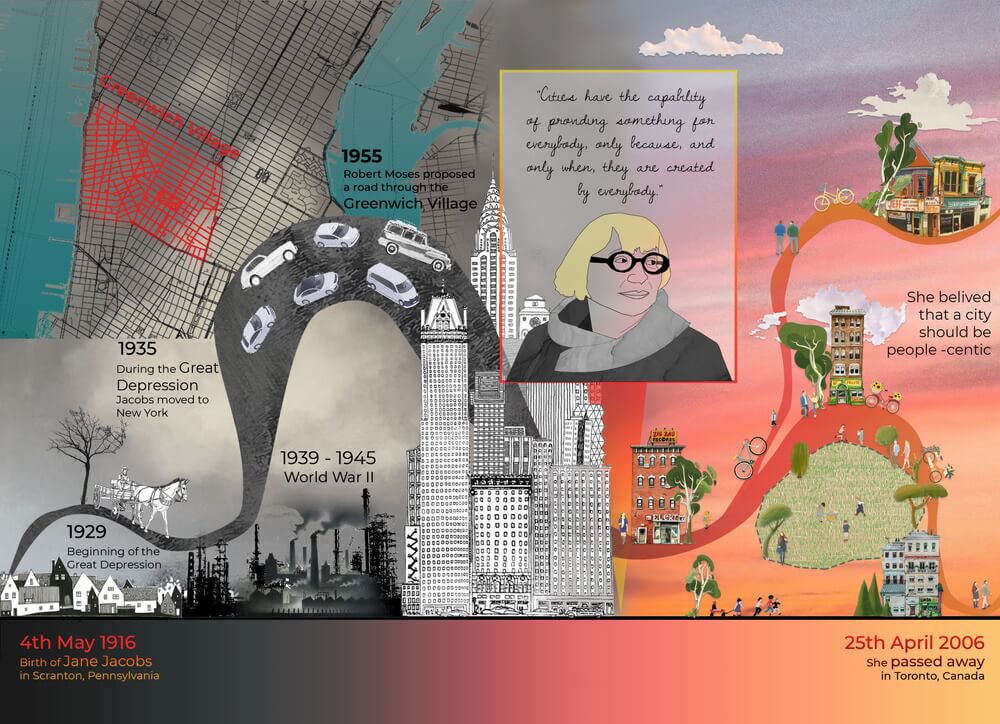

In her life of 89 years, Jane Jacobs essayed many roles from journalist to homemaker, activist to urban thinker, author to protestor, but her stage largely remained the city of New York which came to define her life’s work even after she moved to Toronto, Canada. In New York’s Greenwich Village, Jacobs found her metier beginning with small acts of resistance against the possible disappearance of a neighbourhood garden in which her children played and the imposed plans of an expressway cutting through the Lower Manhattan area.

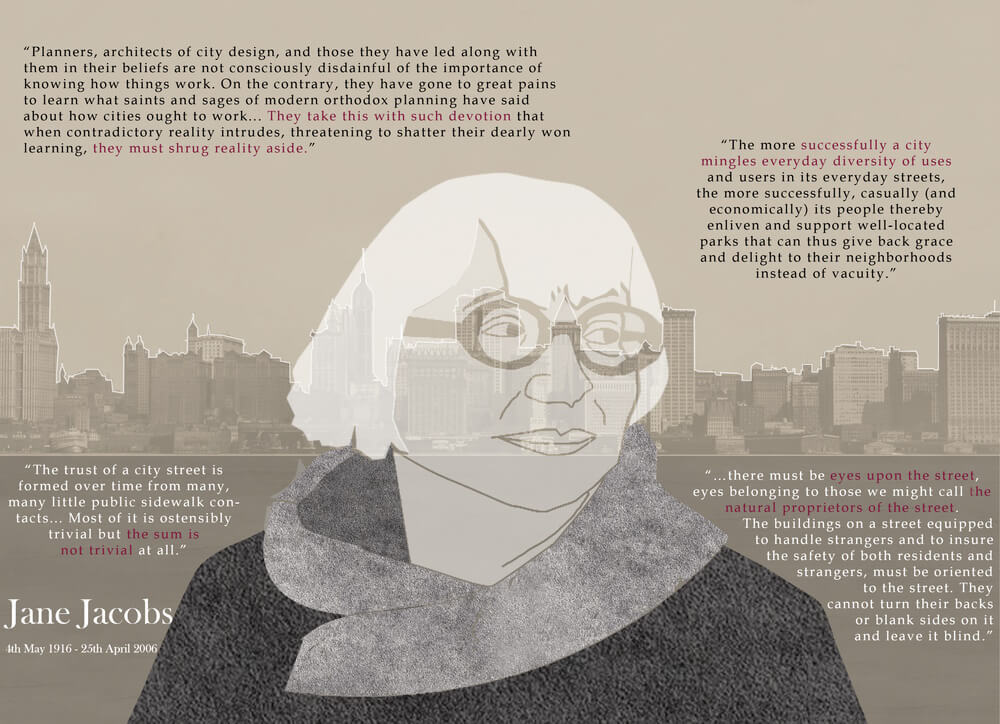

A journalist with Architectural Forum, Jacobs marshalled all her skills of stringing words to make them mean more that their literal sense, to organise communities and people in the protests, to put up protests and resistances which were to become iconic and change the way urban planning would be looked at. Jacobs was recognisable, say those who knew her or wrote about her, with her famous bobbed hair, large glasses on the nose, and a spirited voice that did not hesitate to tell powerful planners and governments to look at what really made cities – people, streets, sidewalks and “the intricate ballet” of it all.

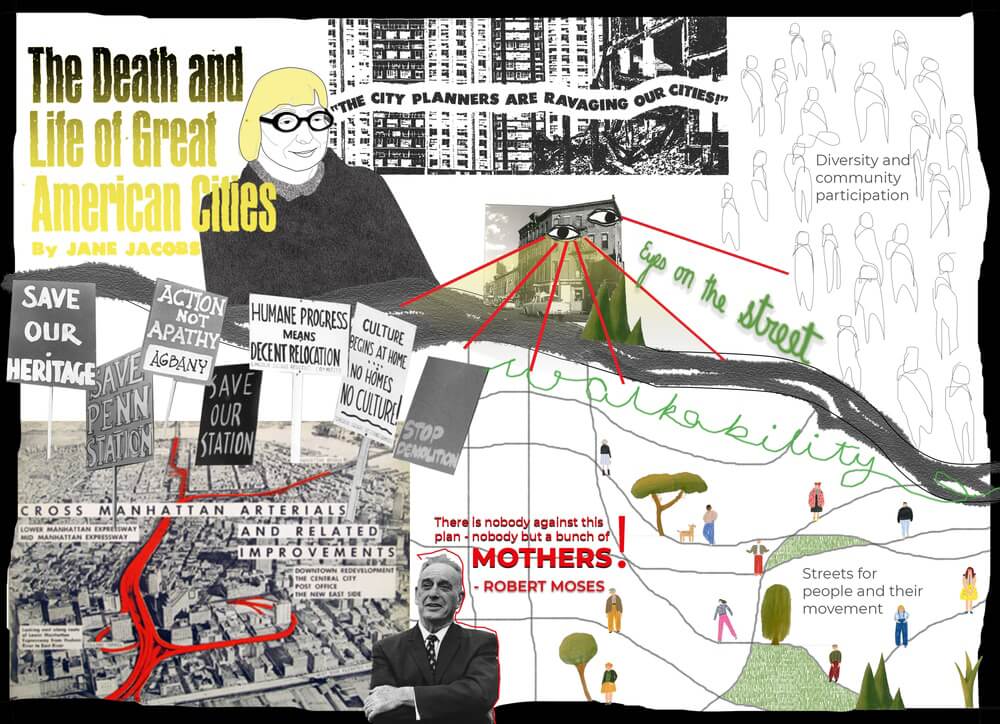

Of the ten books Jacobs wrote, the most well-known are The Death and Life of Great American Cities and The Economy of Cities, which are revered by many around the world but also dismissed by others, especially professional planners. She offered alternative principles of city building and city design, her insightful observations, critiques of mainstream urban planning, and thoughtful alternative ways of imagining cities substantially challenged – if not completely changed – the arc of urban planning in the 1950-60s. Her work continues to inform urban planners in cities around the world six decades later. Jacobs became, though not by design, a leading voice for change in how modern American cities are made in the 20th century. [1]

Under the seeming disorder of the old city, wherever the old city is working successfully, is a marvellous order for maintaining the safety of the streets and the freedom of the city. It is a complex order. Its essence is intricacy of sidewalk use, bringing with it a constant succession of eyes. This order is all composed of movement and change…The stretch of Hudson Street where I live is each day the scene of an intricate sidewalk ballet.

A multitude of diverse job experiences and varying educational interests would have possibly helped her shape her views on the importance of vibrant and diverse neighbourhoods. At the age of nineteen, she left Scranton, where she was born and spent early years of her life, to come to New York where she would go on to live and initiate much-needed transformation in the ways cities are lived and experienced.[2]

Jacobs worked as the associate editor of the then well-known journal Architectural Forum in the 1950-60s when New York was undergoing significant changes. The rapid movement towards modernisation and massive projects came to define city making then, symbolised by planner-administrator Robert Moses whose ideas and plans she opposed, asking questions of him and authorities about where people and their spaces figured in these plans. Billed as urban renewal projects, the highways and large buildings, she believed, were destroying the very neighbourhoods they were meant to revitalise.[3]

The pseudoscience of city planning and its companion, the art of city design, have not yet broken with the specious comfort of wishes, familiar superstitions, oversimplifications, and symbols, and have not yet embarked upon the adventure of probing the real world.

Jacobs clashed with Moses in her battle of ideas of how a neighbourhood should be especially when his multi-lane highway threatened to cut across Greenwich Village.

New York City, in the mid-20th century was, under the Moses spell who was determining the landscape, built environment, projects and everything about the city. Jacobs offered the alternative view to his vision which involved large-scale projects for “urban renewal” such as the construction of highways and the clearance of slums to make way for new developments.

Jacobs vociferously argued, in offices where plans were made as well as on streets with others, that such plans were destroying the fabric of the city’s neighbourhoods and communities. They mobilised against the plan and, along with the entire Greenwich community, eventually succeeded in stopping the highway project.[4] This and other battles helped to shape Jacobs’ vision of what city planning and development must do – look at everyday lives of people, see the ballet on streets and sidewalks, build for them.

There are only two ultimate public powers in shaping and running American cities: votes and control of the money. To sound nicer, we may call these “public opinion” and “disbursement of funds,” but they are still votes and money

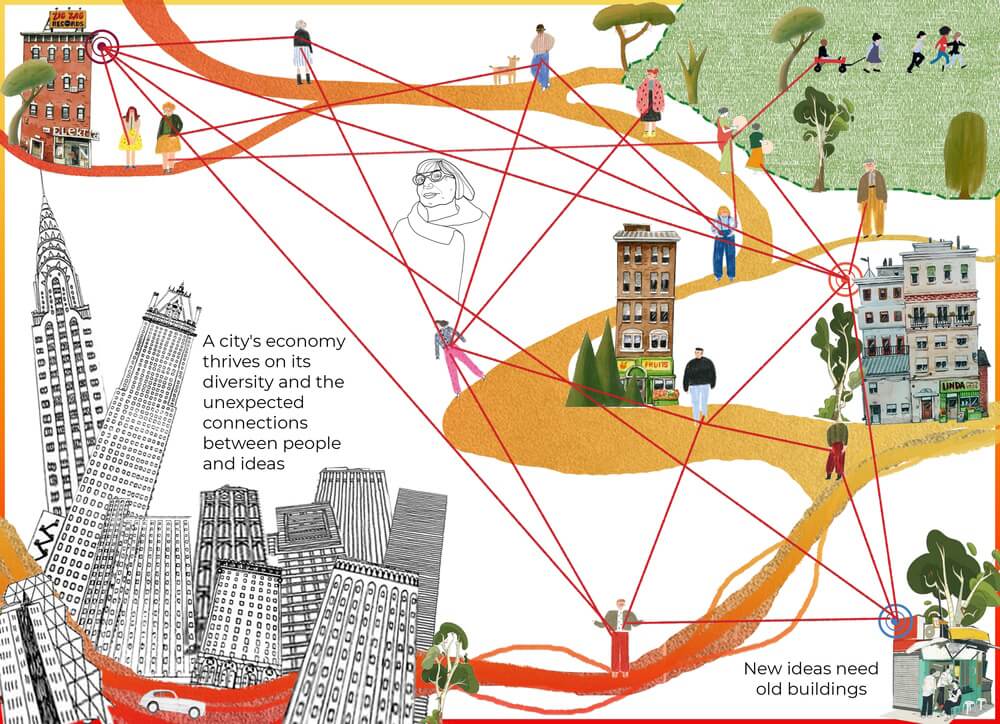

What Jacobs argued, successfully, is that informal networks and connections played an important role in fostering economic growth in cities. She claimed that these networks consist of social and business relationships that exist outside of formal institutions and organisations; they can be valuable sources of information, resources, and support for individuals and businesses.[5]

These informal networks facilitated the exchange of ideas and knowledge among entrepreneurs, which led to the creation of new businesses and the development of new products and services. Beyond that, they could also facilitate economic activity by connecting businesses with potential customers and suppliers which in turn would create more efficient and dynamic local economies. Lastly, they would create a sense of shared identity and common purpose among individuals, their city and their businesses, promoting cooperation and collaboration, and leading to more resilient communities.[6]

Maitreyee Rele graduated from School of Environment and Architecture (SEA) in 2021, where she mostly chose to work on projects on a larger urban scale. She is interested in studying people, their cultures and the society in which they unravel. An unfathomable love for films, art and every other form of storytelling make up the rest of the being.

Cover photo: A representation of Jane Jacobs against the skyline of New York, the city that became her laboratory of ideas and principles of urban planning. Photo: Irving Underhill for The Skyscraper Museum. Illustration: Maitreyee Rele