Viewers stood mesmerised as longitudinal mirrors oscillated in the room and merged with swaying fishing nets – discards of local fisherfolk – with selected organic words inscribed on them. The installation asked people to review what they were consuming from the sea. In another room, painstakingly detailed miniatures of Mumbai’s buildings complete with their balconies, window grills, and air conditioning units were stacked on yellow, orange and green crates used for transporting fish and storing vegetables in the city’s markets. It persuaded people to rethink the city as they towered above it – instead of the other way around in reality. There was more.

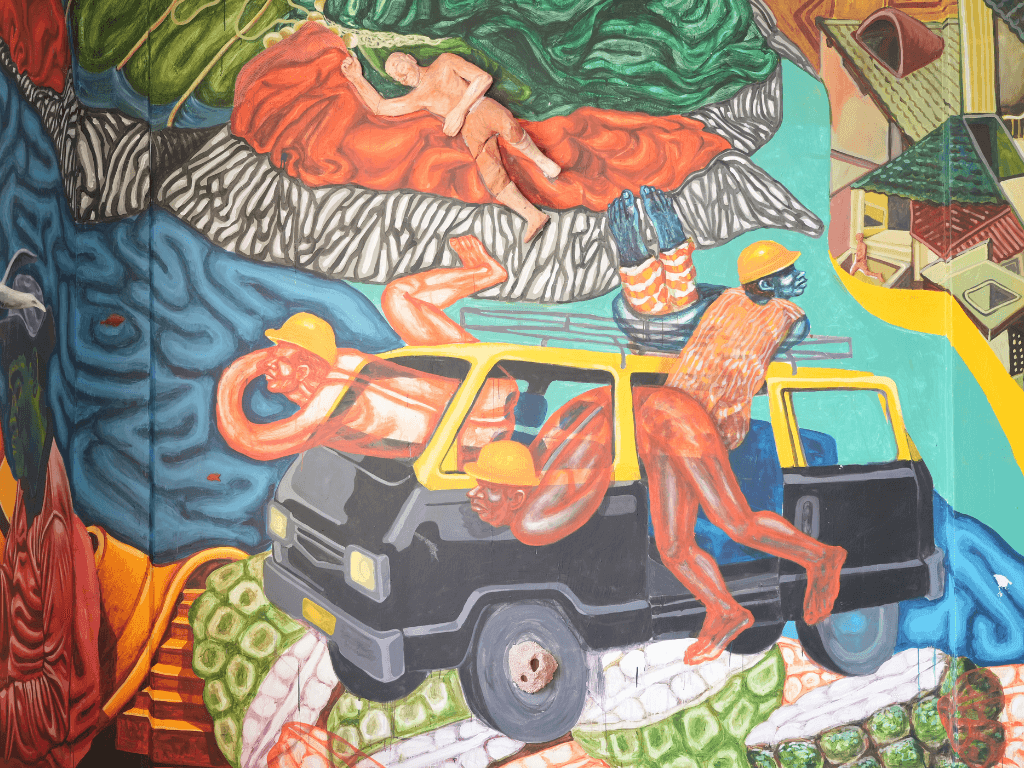

The Mumbai Urban Art Festival at the Sassoon Docks, the city’s oldest and one of its largest fish markets, saw a multimedia and multi-layered fest for two months till February. Titled ‘Between the sea and the city’, it displayed work of more than 60 local and international artists through large murals, immersive installations, experiential exhibits, humongous wall paintings, and performances, all focused on exploring the city’s relationship with the sea – its richness and joy but, more importantly, its ecology and exploitation. It began in a smaller avatar in 2017.

Mumbai’s far-eastern suburb Govandi, dismissed as a place of crime and filth, saw a carnival atmosphere too for five days of February. The city’s backyard, it comprises informal settlements, large numbers of minorities, and people displaced by infrastructure projects; it has among the lowest human development indices in Mumbai. The Govandi Arts Festival, steered by Community Design Agency and the British Council, worked with residents to turn a concretised parking area in Natwar Parekh Compound into an arts venue, signalling diverse uses of public space and different people’s claim to it. The five-day festival saw music performances, stalls with work done by women and girls, and films made by residents who were trained by volunteers.

In tony south Mumbai, the now-iconic Kala Ghoda Arts Festival returned to the heritage precinct after a pandemic-forced hiatus. Bhendi Bazaar – also in south Mumbai and defined by its Muslim majority, small businesses, informality, and decaying buildings – hosted a two-day literature festival, as a throwback to its fading cultural heritage. But urban festivals are hardly new. Venice began its romance with the idea back in 1895, modern Europe has had iterations, and Mumbai, as other cities of India, has had versions of art, culture, and cinema festivals over the decades. This year’s editions saw a post-pandemic resurgence of footfalls.

As the spaces settle back into their quotidian rhythms, questions linger: Do art festivals reimagine public spaces for the larger public good, do they respond to complex issues such as Climate Change, can they play a role in community building and urban planning? The answers are neither simple nor universal. Cities or neighbourhoods have seen different outcomes, but both anecdotal and academic work suggests that cities usually benefit from hosting festivals, despite their limitations.

Photo: Sohil Belim

‘Production of space’

French sociologist Henri Lefebvre, in the post-war 1950-60s, gave us the idea that “social space is a social product”. When art and culture festivals are organised in physical spaces not conventionally designed for them, they help break boundaries imposed by planning, official zoning, and dominant economic use. Whether open spaces such as gardens, parks and markets, or enclosed ones such as galleries, libraries, busy transit stations, festivals nudge people to engage with their cities in new ways. Done with integrity, this can help create badly-needed “social spaces” in a city, give its architecture new purpose, even trigger conversations on complex issues such as ecology.

“At their best, they perform a transformative role in society, celebrating traditions and powerfully expressing the meanings that places hold for people…Our study of 18 festivals across Europe, Africa and the Caribbean found that they can also play a central role in creating more sustainable cities. Sustainability is not just about protecting the environment – it’s also about fostering connections between people and places…(festivals have) the power to bring diverse groups of people together, often with a shared commitment to better lives and places,” wrote researchers Beth Perry and Rike Sitas in 2019.[1]

The sustainability question, the land-sea relationship or its hybridity, was ubiquitous in the Mumbai Urban Art Festival organised by St+art India Foundation and supported by Asian Paints. Installations such as resin models of sea creatures by Parag Tandel, an auto-ethnographer chronicling his Koli community’s relationship with Mumbai, asked hard questions about the city’s interaction with the sea – as a receptacle for waste or cherished natural expanse. This is particularly relevant amidst reports suggesting sea level rise which may submerge parts of the city by 2050.

Non-traditional spaces such as washrooms for men, women, and gender-neutral persons saw art. The imposing walls of the warehouses and ice factory at Sassoon Docks were painted with interpretations of the theme; Kolis were both participants and the muse. A rarely-visited space, the festival drew more than two lakh people to the docks. When the Govandi Arts Festival reclaimed the parking area, residents suddenly realised the expanse of open space available to them.

Photo: Creative Commons

During its Jashn-e-Dastaan-e-Mumbai in January, the 219-year-old Asiatic Society of Mumbai turned its iconic steps into a ‘stage’ for a poetry reading. The cultural group Junoon’s initiative ‘Mumbai Local’ once had artists and scientists talk about their passions. “We took great pains to set it up in public spaces…we avoided rows because we wanted to break the formality. It is not only about finding a place and putting it up, but how you do it that also matters,” says Sameera Iyengar, co-founder of Junoon.

Festivals address the tension between, what researchers have called, contested geographies or spaces in a city and make them relatively more inclusive, even if briefly. Every festival which produces such ‘social space’ is worth its time and effort. Language, then, becomes an important facet of a festival. In Govandi, participants used Marathi and Hindi to tell their stories; the Mumbai Urban Art Festival has installations and performances in Marathi by Kolis, because as Asad Laljee, cultural curator who was also part of this festival, says, “…it’s their festival as much as it is anyone’s. It’s in their backyard, in their stomping ground.”

Journalist-author Naresh Fernandes, also a long-time resident of Mumbai’s Bandra, says that the Celebrate Bandra Festival enabled residents to re-discover their own space such as an old bungalow on Shirley Rajan Road after a play was staged there during the festival. “We need more festivals like the Govandi Arts Festival. We need a Malad Festival, Vashi Festival, Virar Festival so that people in these neighbourhoods discover what they didn’t know and others have an excuse to visit neighbourhoods they haven’t been to.”

Photo: Creative Commons

Transformative power

Urban festivals have been shaped by, and have responded to, the political and socio-economic conditions in which they are planned and brought to life. In bringing issues to the fore, displaying them in anguished or provocative ways through multiple media, festivals can inspire thought, and perhaps, action too. When festivals respond to their milieu, they carry the power to catalyse social change.

Even if a fraction of those who saw Mumbai’s disturbed and dysfunctional relationship with the sea change their consumption patterns or evangelise about it in their networks, small changes would have been set in motion. When issues are presented organically by people directly affected, such as Kolis in Sassoon Docks or Govandi’s residents, they carry an authenticity and urgency needed to inspire viewers. It is not merely the quality of art on display but its impact and possibilities that hold value.

Ecological sustainability, as a theme, has gained ground in festivals. In ‘State of Nature: New Natures’ multi-event in Mumbai last February, poet and art curator Ranjit Hoskote joined artist-activist Ravi Agarwal to invite prominent writers, poets, and essayists to address the ecological crisis on the horizon. International journal ‘The Nature of Cities’ and editor David Maddox invited, for the TNOC Festival, academics and practitioners from around the world “to radically imagine our cities for the future…” The transforming power of festivals was recognised by the international platform United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG)[2] to emphasise the role of culture in planning and building sustainable cities, terming culture as the “fourth pillar of sustainable development”.

Beyond art, mobilisation and politics

The idea of a collective, building a community, around culture is often considered superfluous by festival organisers, but it is an important aspect of negotiating the hard city life. When people join forces to explore ideas or express themselves in creative ways, their socialisation extends beyond their everyday interactions to bind those who are otherwise dichotomised and fragmented in cities, which helps to create communities – ephemeral or long-lasting.

Purists may scoff at art and culture as social or political mobilisers, but when people distill their everyday experiences or larger concerns into creative expressions and claim – or reclaim – public spaces, art and culture are rendered purposeful. The value here is not of the art itself but its purpose and place in urban societies. Offering a collective of people new means of expression and audiences, and mobilising them through their participation in the festival become important.

The Govandi Arts Festival was significant from this perspective. A locality usually forgotten by the city it is a part of, comprising mostly displaced people, making do with cramped and inhospitable quarters as their homes and hardly any civic amenities for leisure and recreation, defined itself as a community. The community identity matters because it forms the bedrock of social and political mobilisation, if handled sensitively and with foresight.

Urban development and city life are harsh, edging out people or violently displacing them as if their lives and livelihoods did not matter. The Kolis and Agris, for instance, among the first settler communities of old Bombay, are barely heard today. When Kolis are drafted into a festival like the one at Sassoon Docks, it offers them a platform to show their perspectives to lakhs of people. Mobilisation of residents in Bandra, through the Bandra Residents Welfare Association, went a long way in reclaiming the promenade and turning it into a vibrant community cultural venue with an amphitheatre which, over the years, hosted hundreds of music and dance performances – and protests.

Studying the role of art interventions in the unrests in 2019 in Chile’s Santiago, among the most segregated cities, university professor Carla Pinochet Cobos found that they helped “people reclaim citizenship…shedding light on how the neoliberal infrastructure of the city has naturalised inequality, social insecurity and segregation”.[3]

Social mobilisation and political resistance have liberally used art, culture, performance arts like theatre and so on through the ages. Urban festivals are no different.

The experience economy

Festivals carry another aspect. The argument goes that they package certain people or parts of a city for the ‘consumption’ of others. This leads to exoticisation or ‘festivalisation’ feeding into the global market, as researchers Marjana Johansson and Jerzy Kociatkiewicz at University of Essex, brought out in their paper. Studying the Stockholm and Warsaw festivals, they wrote, “The urban festival has become a popular organisational form for creating experience spaces and for marketing cities. Festivals are often strategically conceived with the purpose of promoting a ‘distinctive city’.”[4]

The boom in business establishments in the precinct during the Kala Ghoda festival is well-known. “Art is a highly profitable revenue generating industry,” says Asad Laljee. Recounting his experience at Mumbai’s renewed Royal Opera House, he says, “When it reopened in 2016, it led to the promotion of a new kind of economy…The entire neighbourhood started getting painted. Taxi drivers, tea and cigarette stalls, and even the cobbler got more business.”

Jaipur and Kochi have witnessed similar impact during and after the Jaipur Literature Festival and Kochi-Muziris Biennale respectively. However, the festival economy is not a new concept. Most old religious-cultural festivals display this aspect whether the ten-day Ganeshotsav in Maharashtra or the various Kumbh Melas or the less-known Masi Maagam festival in Puducherry when local women sell hyperlocal culinary ingredients among other knick-knacks.

Photo: Creative Commons

There tends to be a “business festival” and an “audience festival” aver researcher-writers John R. Gold and Margaret M. Gold in their book “Festival cities: culture, planning and urban life” published in 2020. Both have art and culture, but the former focuses on economic purposes including tourism to draw in traders and buyers, while the latter concentrates on intrinsic or holistic purposes around themes; in practice, however, most urban festivals tend to be a combination of the two in different degrees.

Revving up retail trade in the festival area or renewing the area’s ties with larger markets are likely to happen. Should they be the intended or only outcomes of a festival, is the question.

Urban planning

With the intrinsic potential they carry for connection and change, can festivals be used as urban planning tools through community participation? Even as events, they have the power to shape the city – or at least the thinking of those who have the power to shape the city.

The Golds, in their book, trace this aspect over time though in European cities only, and show that festivals have been used for economic development and city planning certainly in the industrialised world since the 1930s. The widespread use of festivals as urban policy tools, they write, is because “the festival is an infinitely malleable form of cultural gathering making it the Swiss Army Knife of cultural policy”.[5]

In cities like New Delhi or Mumbai, art and culture are yet to inspire massive shifts in urban planning or policy. The reverse has been more common. Marol Art Village in Andheri suburb has used the spaces available in the neighbourhood to display different art forms from hip-hop cyphers to street art events, and introduced children from marginalised communities to hip-hop, but it has not substantially influenced civic policy or projects in the congested area.

Art and its stories connect people and help build communities – an important role in a city’s increasingly fragmented social life – fabric, celebrate diversity, support each other’s resilience and aspirations. There is always hope that communities can then work towards a sustainable city, and their right to the city.

Smruti Koppikar is a Mumbai-based award-winning journalist, urban chronicler, and media educator. She has more than three decades experience in newsrooms in writing and editing capacities, she focussed on urban issues in the last decade while documenting cities in transition with Mumbai as her focus. She was a member of the group which worked to include gender in Mumbai’s Development Plan 2034 and is the Founder Editor of Question of Cities.

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Cover photo: Trespassers, an installation at the Sassoon Dock Art project/ Sohil Belim