A feminist city must be one where barriers—physical and social—are dismantled, where all bodies are welcome and accommodated. A feminist city must be care-centred, not because women should remain largely responsible for care work, but because the city has the potential to spread care work more evenly. A feminist city must look to the creative tools that women have always used to support one another and find ways to build that support into the very fabric of the urban world.

Feminist City, Leslie Kern, 2020

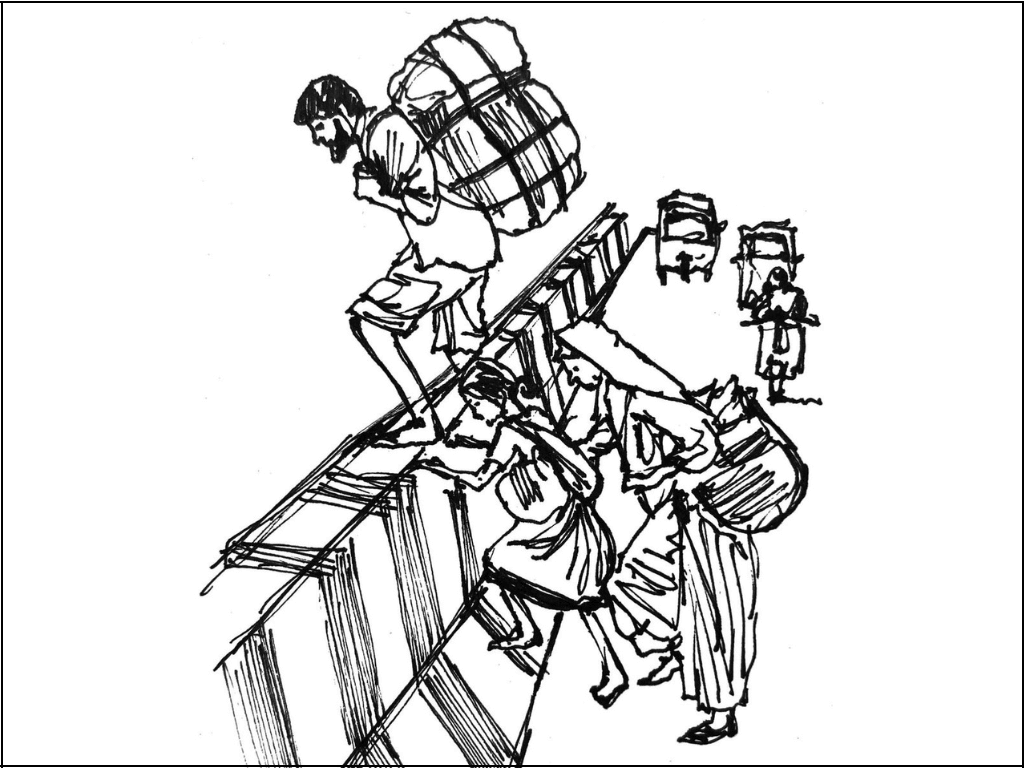

The image stuck in my head some ten years back as I travelled through a fast-growing city of India was a poor family trying to cross a person high barricade to get to the other side of the road (captured in the drawing above) just under the sign which said, ‘Take Metro Escalator to cross’. The depth of blindness that sign exuded was embodied by the poor starving bodies with their entire possessions on their backs, as they struggled to cross.

And here lies the essence of my story — our Indian cities have forgotten to care, forgotten who uses the city the most, who is the most vulnerable to rising temperatures or the flashfloods that plague us every monsoon. Who breathes in the most pollutants that we insulate ourselves in our AC cars from? Who struggles on the broken pavements, the absent ones? For millions of citizens who fall through these cracks, the city is a hostile envelope that never imagined them as a participant and user.

John Rawls’ treatise set out the basic premise that everyone must enjoy ‘equal basic liberties’ for equal opportunity to equal outcomes (Theory of Justice, 1971, p. 7). In his 1968 book The Right to The City (Le Droit à la Ville), Henri Lefebvre lays down the manifesto of ‘spatial rights’, where citizens should not be imagined as consumers but rather participants in creating the city, shaping the urban environment they inhabit, and thus shaping themselves. The ‘everyday life’ of citizens requires democratisation of cities where ‘rights’ are the participatory process of inclusion — the citizen’s inalienable right to decide for themselves how the city behaves towards them (King 2019).

Since the city is a major player in who we become, we have the right to shape it to be what it needs to be (Harvey, 2008). A city must be more than just an economic playfield where absorption of surplus displaces and dispossesses the weakest of the citizens – the poor, the underprivileged, the marginalised. Yet, today’s neoliberal cities of India and outside view citizens as workers from whom labour must be extracted to fuel the great economic machine. Falling by the wayside are needs – of social spaces, companionability, even basic needs of the human species to the point of depriving citizens of the very air they need to breathe and the water they need to survive. India’s metropolitans today struggle to breathe; they experience drought and floods in the same weather cycle as lives are claimed by extreme heat or cold.

City as ultimate democratic society, a site of equality

Cities of the world have a key function within democracy, as the space where citizens escape parochialism and community controls over individual lives; and achieve their true potential with access to equal opportunities and resources. A city is the ultimate act of an inclusive democratic society as it impinges on ‘civility’ — a political act that allows us to expose our vulnerable selves to strangers and expect them to be civil enough to protect them. It is through the effective creation of mixing of populations that true democracy and social equity is created. While mixed housing or public spaces accessible to all, connected spaces, transparency and visibility do not in themselves distribute wealth, it equalises our experience of urbanity and our city, thus making everyone an equal stakeholder with shared concerns.

The city is also an important vehicle for the aspirations of equality of historically marginalised communities like the poor, women, caste and gender minorities, and people with different bodies – the differently abled, the old and children. Thus, it becomes extremely important that the imagination of the city is embedded in the needs and wants of these historically ignored populations. Cities designed by the poor, or by parents and caregivers are the new ways to look at urban architecture, which provides this spatial justice to our most vulnerable.

So, what does this ‘Carefull’ City look like? Opposed to its more famous cousin – the City Beautiful or the Garden City of the late 1800s — articulated by orderly urban space with centralised amenities and rings of houses around it (Wilson 1991) that continues to be much of the imagination of cities in India — the ‘Carefull’ city designs itself around the concept of care giving and care needing – recognising that all citizens fall in either or both such categories.

A ‘Carefull’ city not only beseeches us to look away from cars that have created the monster cities we have today, but also to centre ourselves around human beings and human needs. A ‘Carefull’ city is based on the ‘needs, demands, and desires’ (Kern, 2002) of the women, the disabled, the queer, the caregiver, the aged, the poor, the migrant, the child, the teen and the young. It hinges on understanding that our experiences of the city are different based on where we are placed in the power matrix, and this differentiation needs to become an active part of the design to build equitable cities.

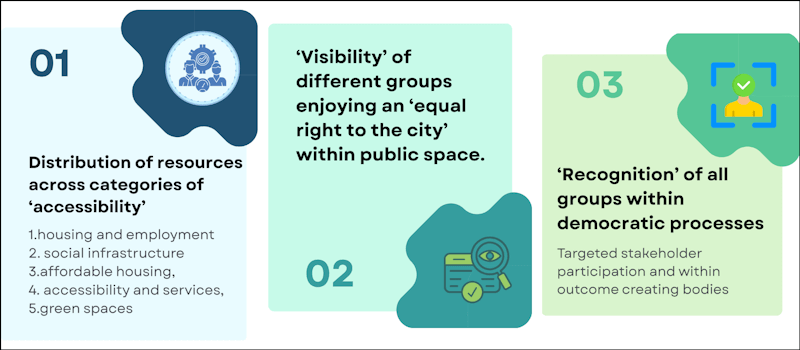

Diagram: Fincher and Iveson, 2008

Why should we build a care–centric city?

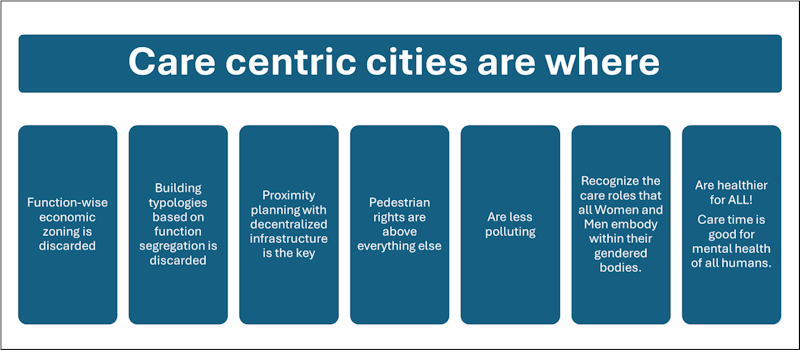

Other than the fact that care-centric cities are just the right way to go about the business of urbanisation, because they recognise the care roles that all women and men embody within their gendered bodies, care-centric cities are also more sustainable and less polluting, understand people’s daily lives, reduce travel times and overall, allow every human being to spend more time for themselves or with their loved ones than separating lives into worker bees and home bound individuals.

Care-centric cities are also more beautiful as cars and car infrastructure gets replaced by people and people-centric spaces, greens and spaces for birds and bees. Major research in recent years have shown how beauty and aesthetics are incredibly important for brain and physical health, how a few moments in nature allow our body and brain cells to regenerate, and how air pollution is a major reason for dementia (Klein 2025; Hiromoto 2025; Fallik 2025). The green spaces, parks and regenerated wetlands which become spaces of care are also the exact antidote that our cities need today to become climate adaptive, reeling under heat waves and flash floods as they are. Care-centric cities are really the solution to many of our urban crises today to be ignored any longer.

What happens when we do not centre ‘care’?

We discriminate. When we eliminate footpaths, we discriminate against women, children and the elderly, as these are the groups with least access to private transport. Lack of round-the-clock public transport is a safety issue for women, as they prefer public transport rather than private later at night. The lack of last-mile connectivity hampers women’s everyday life access to the city, as they use the city intensively for their myriad care duties. Women have multiple roles to perform throughout the day which must be supported by short trips or trip chaining. Disconnected infrastructure wastes time, leaving them time-poor.

Safety based on intensive surveillance discriminates against women, as they are tools for policing behaviour more than criminal activities. Opaque streets feel more hostile to women with their socialisation of the ‘geography of fear’ (Valentine 1989; Condon et al. 2007; Pain 1997).

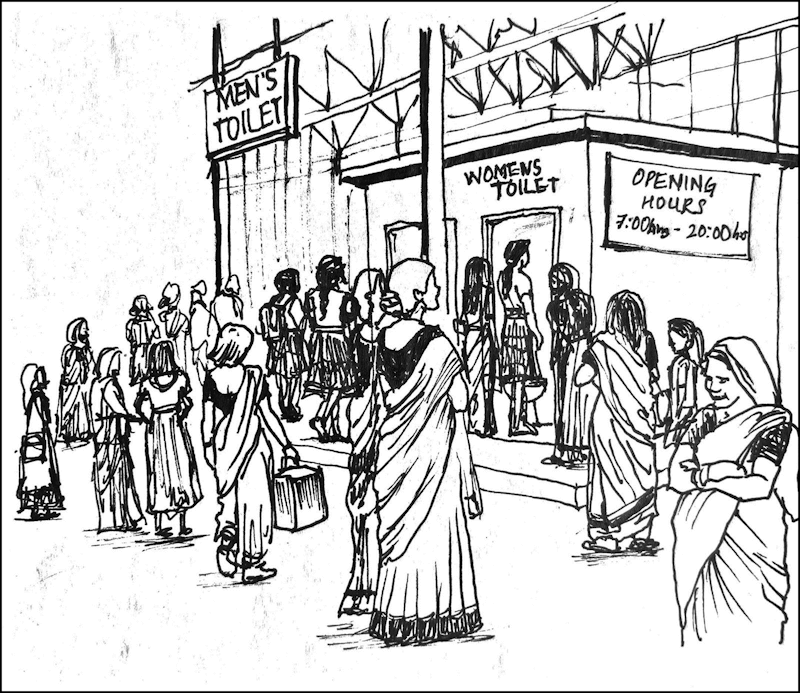

The lack of adequate toilets matters to women more as they are socialised to not ‘go’ publicly as freely as men, encounter harassment if they do, and are clothed inconveniently to be able to do so with ease, other than obvious aspects of menstruation needs and other bodily needs. Even where public toilets are available, they are not sufficient in numbers or are inadequately designed. Building codes in India calculate occupancy loads as 2/3: 1/3 between men and women for public spaces, affecting the total number of stalls available, resulting in long queues outside women’s toilets. Design of public toilets also ignores women’s performative bodies, and their overburdening of care duties. Further, this binary segregation of toilets leaves large sections of gender-fluid people without this very basic necessity within our public realms.

Women have less time to formally socialise and they derive relaxation and socialities along with their everyday care and economic work. Possibilities for chance encounters of companionship and camaraderie by eliminating social spaces along their everyday create isolated lives of loneliness. Opaque housings with single floor apartments or suburban lives of car dependency are especially detrimental to them. Absence of pocket parks along easy everyday infrastructure affects women’s ability to access leisure. Opacity of green spaces to everyday commute routes make women insecure about using such infrastructure safely. Segregated age-specific open spaces serve women less than integrated spaces, as they access these spaces as a part of their care roles.

Diagram: Monolita Chatterjee

What can a care-centric city look like?

Let us imagine a street in such a city.

The grounds are left free for people and their everyday lives. Space-starved and congested areas can use spaces trapped in private front setbacks transforming into spaces for pedestrian movements, pocket parks, constructed wetlands, resting and playing with reintroduced native species of flora and fauna. Wide pavements with open street edges – out of the imagination of Jane Jacobs, create lively and safe spaces for all.

What if a traffic junction was designed around pedestrian movements? Times of exchange were allotted based on human possibilities with an understanding of care giving or care needing bodies. Shortest distance travel on grade was given not to the machine but to the human body.

Let us ask a few questions then. Cities should be designed around questions and interrogations of inclusion and the shape our everyday life. What would parents and caregivers need from a city? How do the old gracefully age? Where do teenage girls play? Can our child cross the street and access a playground? Will I be able to see him from my window?

These questions should not hesitate to examine normative assumptions over our lives and our bodies. How do women want their homes? Do they mind being trapped in opaque homes where no one can see daily slow (or major) violence perpetuated on their bodies and minds? What is this concept of privacy? Who are we private from? What do we hide? Do our opaque facades with high boundary walls protect us or is it guarding over women’s bodies, and their freedoms. Do women really need high walls? What freedom is there inside ‘walls’?

So, what really is a Feminist City?

The Feminist City is a city of beauty, love and care. It is a city which is constructed around joy and laughter, around the recognition of our need to be with our loved ones. It is a place where children can play on the sidewalks and side streets, the fishmonger lady can hawk her fare at street corners at will, the cabbie driver – male or female – can find a cool spot for a mid-day snooze, or a toilet within easy distance. Where anyone can read a book under the shade of the tree while listening to birds. Where a group of friends can take a walk, any time, for any reason, down any odd street and expect the world to be civil.

It is a place which accepts all of us, and visualises a future that all species – plant and animal, can share equally. A just and rightful space for us to engage at will, unconditionally, without reason. The city that allows us to be the best of ourselves, as humanity, and as Earth.

References:

- Harvey, D. (2008, Sept/ Oct). The Right to The City. New Left Review.

- Rawls, J. (1971). Theory of Justice. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wilson, E. (1991). The Sphinx in the City. London, England: University of California Press.

- Condon, Stéphanie, Marylène Lieber, and Florence Maillochon. 2007. “Feeling Unsafe in Public Places: Understanding Women’s Fears:” Revue Française de Sociologie Vol. 48 (5): 101–28.

- Fallik, Dawn. 2025. “Landmark Meta-Analysis Identifies Air Pollution as Modifiable Risk Factor for Dementia.” Neurology Today 25 (19): 12.

- Hiromoto, Julie. 2025. “Brain Economy Opportunity: Brain-Healthy, Climate-Positive Cities.” Urban Land, August 14.

- King, Loren. 2019. “Henri Lefebvre and the Right to the City.” In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of the City, 1st ed., edited by Sharon M. Meagher, Samantha Noll, and Joseph S. Biehl. Routledge.

- Klein, Ezra. 2025. “Opinion | A Breath of Fresh Air With Brian Eno.” Opinion. The New York Times, October 3.

- Pain, Rachel H. 1997. “Social Geographies of Women’s Fear of Crime.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 22 (2): 231–44.

- Valentine, Gill. 1989. “The Geography of Women’s Fear.” Area, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) 21 (4): 385–90.

Sketches by: Zamina Abdul Salam, Aleena Amjad, Anupa Mathew, Jishna V B, Zeba Abid, Anupa Kurien, Georgina John

Ar. Monolita Chatterjee is a Kochi-based architect focusing on design for gender response, inclusion and sustainability with projects ranging from residences to resorts, commercial offices to housing. As a partner of ‘Design Combine, Architects and Designers,’ www.designcombine.com she has won multiple state and national level awards for architecture, heritage transformations, sustainable design, and adaptive reuse. Empanelled with the ASI Southern Region, and Cochin Corporation, Chatterjee has worked on several urban designs, water edge development, conservation and heritage projects. She teaches at KMEA College of Architecture, has been a member of the Kerala State Government for Design and Urban Policy Commission, and is the Founding Principal of gender rights NGO ‘Raising Our Voices Foundation.’ www.raisingourvoices.org