‘In the contest of chaos, where nature weeps,

a tale of debris, in silence it seeps.

Climatic disasters, with fury they roar,

leaving a trail of destruction, on every shore.

…

Mountains of trash, an unsightly mound,

consuming the Earth, like a relentless hound.

Plastic seas and polluted air,

a legacy of neglect, we’re forced to bear.’

These evocative lines from Debris, a poem by Vibha Galhotra resonate in the space between imagination and art when it comes to non-artsy, science-heavy, people’s issues such as climate change. What does it mean to distill it into art? Can definitive lines be drawn to capture the ebb-and-flow of an issue so vast, one with profound impact on millions of people and the planet itself?

For certain, these are not today’s questions. Artists have pondered over them for ages. Rabindranath Tagore left us a bouquet of natural landscapes. Well-known figures like Akbar Padamsee, Ganesh Haloi, Satish Chandra, Manu Parekh, and Paresh Maity, to name a few, considerably enriched that. Younger and lesser-known artists have engaged with nature and landscapes, flora and foliage, to create beautiful and breath-taking canvases. Contemporary artists have attempted to merge traditional art approaches with photo collages, used mixed media, even integrated their art into AI if not used AI to make art about, ironically, nature.

However, climate change is quite another subject. It is nature and forces of weather expressing themselves but more than that. It is about science but not limited by it. It is about places, the cities and villages, but not merely that. It is about people, every aspect of whose lives are roiled by its impacts and the extreme weather events turn more intense and frequent every passing year with little relief in sight. How is something as complex and multi-dimensional, global but local at the same time, as climate change manifested in art? A few have attempted to dive in.

Years ago, urbanists Dilip da Cunha and Anuradha Mathur gave us SOAK, a volume in words and exquisite illustrations of the blurred boundaries between land and water in Mumbai. They showed the city as an estuary with surfaces having varying degrees of wetness, folding and stretching into one another. It was almost-art; it brought home the natural watercourses of the city, the blocking or disruption of which leads to massive flooding during every monsoon. It was not merely a book but an aquatic portrait of a city created from the sea.

Climate change is a different beast for artists – for some, it’s too complex and remote to distill into their work, for others, it’s worth grappling with. Art on the subject can communicate beyond the silos of language, form, news, caste, gender and other markers. Imagination, inspiration, medium, form, space, texture, light and everything that makes art is called upon. This art can reflect the action around climate impacts, the dead negotiations at the global level, the unusual nature of weather itself and more.

If art is about a moment in time, then should art not engage more with climate change which is humanity’s big challenge next to war? How should it raise consciousness, foster dialogue, stir action? How does art, which is at once a personal expression and a social comment, go beyond breathtaking landscapes? The questions are demanding; a few have tried to address them.

Of creatures, climates, and cultures

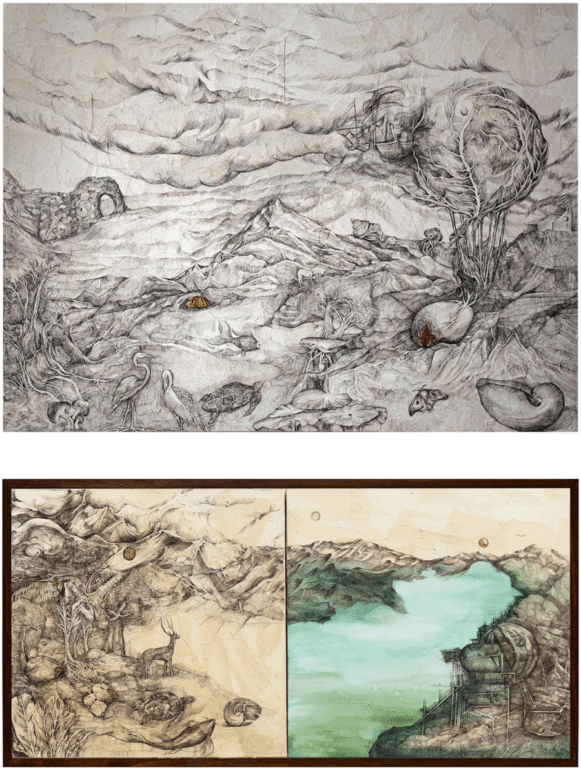

Meghna Singh Patpatia, a visual artist based in Mumbai, is one among them.[1] Her art reflects natural elements and creatures adapting to diverse ever-changing landscapes. “My art practice began with rendering natural elements, following the journey of creatures being drawn to light. The phenomenon of transverse orientation where all beings are drawn to light intrigued me. Through it, I drew a parallel to how humankind in the name of progress is destroying our natural resources,” she explained to Question of Cities.

In her frames, light plays a role in the growth of sentient beings; it is possible to see parallels with biodiversity that’s globally threatened by climate change. “My love for the natural world is expressed through what I create, it is a reverence for the creatures that have survived and witnessed so many changes in our environment,” Patpatia adds. This intersection of nature, science and human beings expands, creates, and displays art beyond the mere beautiful or self-indulgent.

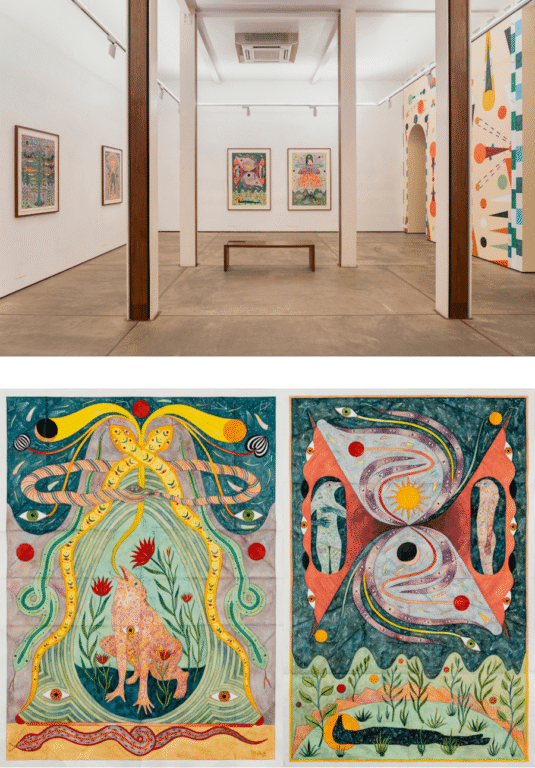

Artist Rithika Merchant showed at TARQ gallery a few months back. The exhibition Pillars of Fruit and Bone[2] built on the idea of creating a sustainable utopia away from the Earth. The introduction of imaginative worlds and creatures in it was, in my interpretation, a way for the artist to soothe herself in the face of climate change. Merchant often uses characters as substitutes of humans to reflect the concept of abiogenesis-life emerging from non-living matter billions of years ago. Her series Birth of a New World (2021) came during COVID, where she began imagining what comes after the Holocene and Anthropocene.

Merchant’s recent series Terraformation (2022-2023, Kristen Hjellegjerde) and Pillars of Fruit and Bone explore life away from Earth. Is leaving the Earth, besieged by the climate crisis, even a possibility or would the possibility seen in her frames goad people into action? “People are drawn to Rithika Merchant’s work for the strong narratives and the quiet, intricate details. It leaves viewers feeling awe and hope, like they’ve stepped into a world that’s both familiar and entirely imagined. It opens space for people to think freely, to dream a little,” says Hena Kapadia, director of TARQ.

Rooted in community

For many, the very act of walking into an art gallery, let alone bringing a canvas back home, seems exclusive and exclusionary. Galleries might be open to all but they are still spaces where many do not feel belonged. Locating art in a relatable way, rooting it in familiar cultural symbols and ethos, and taking it to people are ways that artists from communities have embraced. Parag Tandel, who hails from Mumbai’s fishing community, the Kolis, is among them.

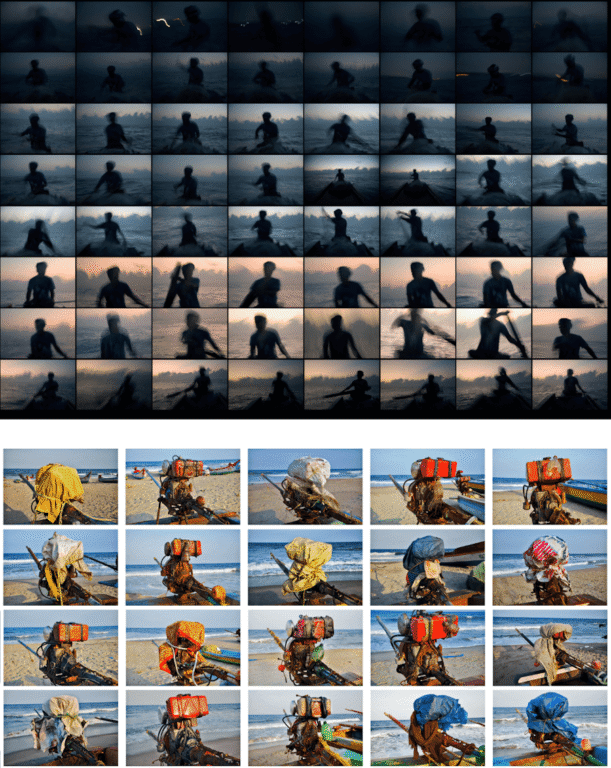

For Tandel, who has shown at galleries and at more accessible community venues, art takes shape at the grassroots. Having lived near the sea for 47 years, his work reflects how the Kolis live with the water and what the vast sea means to them. “I think about the impact. It’s not just a picture but it’s about how to bring new knowledge that people can understand,” he says, given how climate change and urbanisation are complex issues. What bothers him is that climate change “is becoming a corporate thing with many large companies doing CSR funding” but he prefers to engage with the community.

Like him, a number of artists have been working at the intersection of art, research, information and community to create inter-disciplinary work. Besides Navjot Altaf, Ravi Agarwal, Vibha Galhotra, Sonia Mehra Chawla, Meghna Singh Patpatia, Ranjit Kandalgaonkar are some contemporary names.

“Representing climate change is not necessarily showing ice melting or the polar bear in the Arctic. I look at it from the social equity angle – what is the experience of climate change, what was the experience of the environmental crisis,” explains Ravi Agarwal who bridges art and activism with his interdisciplinary practice as an artist, photographer, environmental campaigner, writer and curator. His work, Else All Will Be Still[3], is a collection of photographs of the fisherfolk in Tamil Nadu on how the community perceives the changing sea, what their cultural relationship with it is, and so on. He also speaks about the pollution in the Yamuna River through Toxics Link.[4] Agarwal maintained a detailed diary which was later published as Ambient Seas, an introspective volume of resistance and critique, and a quiet call for action.

Of stories in stone

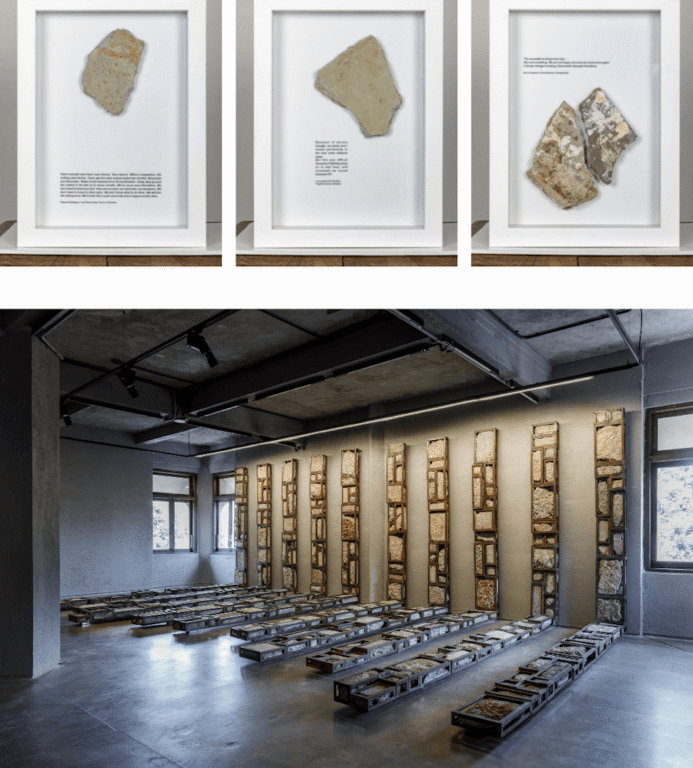

Stone and rubble as art to reflect on climate change might seem far-fetched but it’s been done. Rubble is evocative – whether in cities bombed, or under perennial construction, or as fistful carried from one place to another as memory. Vibha Galhotra’s Solastalgia: The Weight in the Air[5] explores the distress caused by irreversible environmental changes and reflects on the experiences of people forced to migrate in the face of extreme weather conditions. “It’s a very big satire on ourselves. I feel we are living in a time where we are creating these situations and then trying to solve them,” says Galhotra.

Her work of collecting rubble from across the world – different climatic zones, war zones, places affected by floods and earthquakes – is a refreshing approach. It is a signifier of the climatic as well as the sociological toll. “Because of severe drought, my family and I moved permanently to the river some distance away but this was difficult because of the fighting going on in that area…” says a Lau woman in a camp in Ethiopia for Sudanese refugees, on one of the rubble frames. Galhotra’s installation Pieces of memory talks about such rubble. And suddenly, art, war and the environment are fused in one place.

Of the past, present and future

Art is not merely an elitist indulgence but also a form of documenting the changing environment around us. The show A Splendid Land: Paintings from Royal Udaipur[6] , at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art in November 2022, displayed a series of paintings with landscapes, monsoon patterns and climatic changes to celebrate, among other things, the city’s water resources.[7]

Patpatia explains that art practices in Indian history have been an intrinsic part of rituals. “I am deeply inspired by mythological stories that show our co-existence with other species. I also work with found object assemblages which are reflective of us imitating nature,” she explains. This affirms that although art galleries are the designated formal spaces for art, people have lived with artistic forms in daily lives and experiences. Diving into this is perhaps a key to unlock the intersection of climate change and people’s lives.

A buffet of interpretations

In our quest for art on climate change, Question of Cities asked artists to create and share their interpretations. Here are a few our team selected:

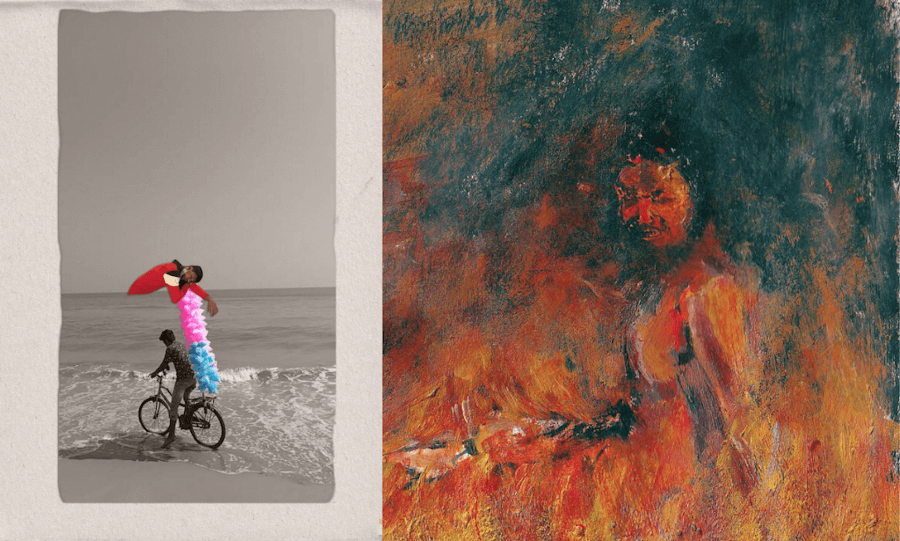

Sunny Kumar Gupta, an independent architect and researcher, says: “Climate change is not just a disaster waiting to arrive. It is already here, in the mundane, in the repetition. It is not a storm. It is this—the quiet violence of being exposed, daily.”

The man with the cycle has no escape from the vast and uncertain daily waves of climate change. His other self—floating, half-limp, half-longing—seeks relief, but knows there is none.

The fire too, isn’t metaphor—it’s presence.

Not apocalypse, but a shift in the air.

You see it in the tin sheds where workers build cities they won’t live in.

In those delivering food through 45°C heat.

You don’t need prophecies to feel climate.

You just need to stand where cooling is a luxury and pausing is not an option.

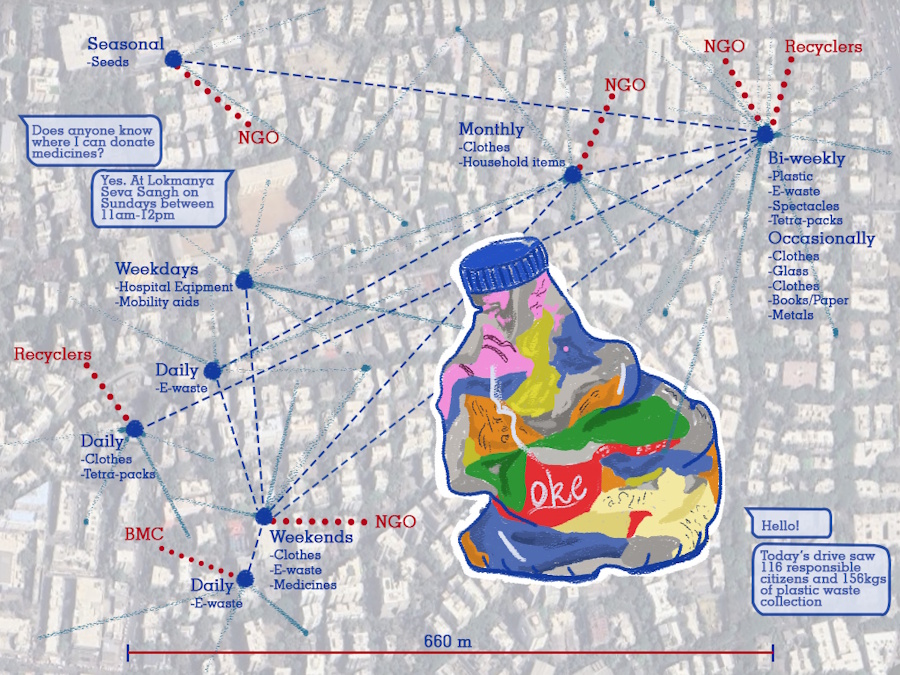

For Trisha Salvi, architect and artists, climate change is innately connected to community and the waste produced. “Over the past five years, I’ve lived in five Indian cities, witnessing both the growing intensity of climate change and unsustainable ways of urban living. City dwellers like us are trapped in systems that promote over-consumption of food, clothing, electronics, plastics, and more leading to increased waste and environmental degradation.” Her illustration came from her work on waste collection and disposal.

Her illustration is about a growing community in a location in Mumbai that is concerned about climate change, consumption, and waste. The nodes in the artwork, plotted on an actual map of the neighbourhood, represent local sanghs, institutions, shops and individuals taking the initiative and time to address this and be the change-makers on this issue.

Madhura Patil an architect, artist and resident of Thane who grew up amidst trees, flowers, grass in lush green gardens, says: “I’ve felt immense grief watching it all disappear. This drawing began as a simple memory of how nature felt such an ordinary part of life.”

For the next generation nature might become something rare and distant. With this piece, Madhura captures the wonder in a child’s eyes when looking at something they should have grown up with. It’s a reminder to protect what still remains of nature.

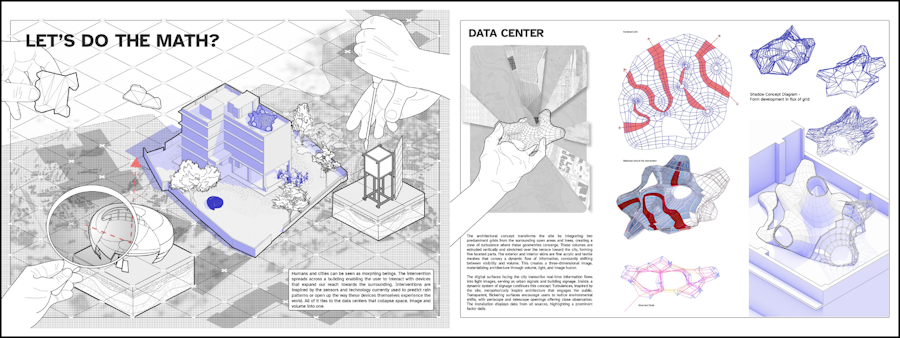

Ronak Soni’s Let’s Do the Math aims to establish a relationship between climate change and people, addressing the age of allergies and environmental hypersensitivity. The goal of Let’s Do the Math is to nudge people towards a personal engagement with climate change. By integrating human, digital, and natural intelligences, the pavilion encourages introspection and action, promoting sustainability.

When artists engage with climate change, and experiment with mediums, forms, textures and material, they are not just making art but capturing their unique perception of the present and interpreting it for the future – for all of us.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect and urban practitioner, works as illustrator and writer with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, and later as Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Cover photo: Rithika Merchant’s exhibition ‘Pillars of Fruit and Bone’. Credit: Nikeita Saraf