“I always heard that America is good, that there are so many chances, but I can never explain what kind of suffering I had here.”

These are words of Marjina, an abused Bengali domestic worker, during her time in the US. Investigating the why and how of the creation of South Asian domestic worker organisations reveals a diaspora of South Asian immigrants that were like Marjina: they took a chance and came to the United States (US) in search of opportunities but were met with unexpected forms of abuse. Along with navigating a new American cultural context and an environment laden with unknown labour laws, domestic worker organisers were engaging—and disagreeing—about the role of class, caste, gender, and labour.

Unique aspects of South Asian cultural life influenced the creation and functioning of domestic worker organisations…Moreover, because South Asian women entered the domestic work industry at a time when greater proportions of immigrants began working within it, their experiences are critical to understanding why campaigns for greater legal protections for domestic workers emerged in the early 2000s and eventually resulted in the passage of the country’s first national legislation dedicated to protecting domestic worker rights.

Shamita Das Dasgupta, one of the six co-founders of Manavi—one of the earliest organisations dedicated to addressing domestic violence against South Asian women—noted how the arrival of South Asian immigrants in the years following 1965 earned the title of “model minorities,” as they scaled up the American economic ladder of success (Dasgupta 1999).

In 1965, 582 Indian immigrants entered the US, 10 years later, it was 14,939 (Mitra 2003). Along with an increase in the number of immigrants, there emerged differences in their occupational backgrounds. The first wave of immigrants were highly educated professionals: medical doctors, lawyers, engineers, doctoral and post-doctoral students in the sciences, and other skilled professionals (Bhatia & Ram 2018). Husbands were usually the primary visa holder. Families were soon reunified through the INA’s second preference category, which allowed spouses and children to be sponsored for immigration.

The number of Indian professionals decreased from 60 percent in 1970 to 30 percent in 1990. Later immigrants were less educated and worked in industries like retail, food service and domestic work. It was the first wave of South Asian immigrants—mainly professionals—that came to characterise depictions of the South Asian diaspora as a model minority group by the American public.

An article in the Winter 1992 edition of SAMAR illustrates the division between middle and working class South Asian immigrants (SAMAR 1992)…The class difference yielded a one-sided relationship, in which the employer exerted influence over the workers. It also showed how the South Asian diaspora was not a monolith. The label of model minority did not reflect the experiences of South Asian immigrants engaged in labour considered unskilled like taxi drivers, restaurant workers, domestic workers, and other professions that involve long hours and low wages.

The early organisations

South Asian women in the early 1970s did not find help at mainstream American domestic violence organisations due to cultural barriers, and they did not yet interact with South Asian organisations because none existed for them. Thus emerged a feeling among the South Asian organisers in the 1980s to begin advocating on the behalf of these women. South Asian specific domestic violence organisations emerged “spontaneously” in response to women demanding assistance.

Manavi, the first organisation dedicated to helping South Asian women fight domestic violence, was formed in 1985. The co-founders considered themselves “runaways from mainstream feminism,” which in their eyes had not adequately helped women of colour (Abraham 2000). It is important to note that these organisations were not initially dedicated to helping specifically domestic workers (but) they formed the basis of organising that came years later to improve labour conditions within the domestic worker industry.

Domestic workers became integrated into these organisations as more and more women pursued domestic work. South Asian women entered the domestic work industry at a time when African American participation was declining and a greater share of immigrants were taking domestic worker jobs. The share of employed domestic workers who were Black shrunk from 42 percent in 1950 to only 6 percent by 1980 (Nadasen 2015).

The path of South Asian women to domestic work was marked through “informal networks and means such as word of mouth or classified ads in the ethnic press” (Varghese 2013) and promises of “high wages and sponsorship for a U.S. ‘green card.’” Seeing ads in South Asian newspapers in their home countries, they chose to take a chance and immigrate in search of work (Daily News 1997). Upon arrival, they navigated a country in which the language, culture, and way of life was entirely foreign.

Class and caste mattered

Class dynamics brought organisers in conflict with one another and forced debates about how domestic worker organisations should be structured. The breakup of the Domestic Worker Committee (DWC) within Sakhi for South Asian Women illustrates the critical role that class played and also illustrates how helping South Asian domestic workers involved different considerations than helping South Asian women escaping abuse.

Sakhi for South Asian Women was created four years after Manavi, in 1989. It was created by co-founders who were “professional women in law, film, finance, and computer science” in New York (Gupta 2006). It began a domestic violence programme that, like Manavi, provided social services to women experiencing abuse. Many of the women that came to Sakhi were domestic workers in New York; this pushed the organisation to focus on the abusive relationship between South Asian employers and employees.

In 1994, Sakhi created the Domestic Workers’ Committee (DWC) to specifically address the concerns of domestic workers such as “unpaid wages and abusive and exploitative working conditions” (Mishra 2016) and included a “women’s hotline, counselling programs, and literacy classes” (Chansanchai 1997). As the DWC began to grow, there were increasing conflicts between members about the priorities of Sakhi. The introduction of domestic workers expanded the scope of the organisation’s work to include domestic workers suffering at the hands of employers, who were usually South Asian themselves. This led to debates within the organisation…This meant rethinking how domestic violence operated in its relationship to labour.

Class caused rifts between domestic workers within the organisation and organisers. Domestic workers believed the organisation should be led by those within the industry. They felt they were “expected to follow middle-class women’s perfection of working-class priorities.” Even the founder of Sakhi, Annanya Bhattacharjee, was critical of the South Asian women within Sakhi. Additionally, domestic workers within Sakhi preferred protest strategies that were more radical than the middle-class women. The DWC changed from “simply offering support services to domestic workers” to “target[ing] employers” outside the homes of employers. It would stage protests against employers to put pressure on them to pay wages to workers. In April of 1997, Sakhi decided to separate the DWC from itself which resulted in “a bitter struggle” (Gupta 2006).

What is explicitly missing from the discourse surrounding Sakhi’s dissolution is the relationship between class and caste, an integral part of South Asian life and especially that of domestic workers. For centuries, one’s caste status has dictated the labour they complete. The caste system, which assigns individuals at birth a certain identity based on their family history, has been integral to domestic work in South Asian countries and informs how families complete household work.

Workers’ Awaaz and Andolan

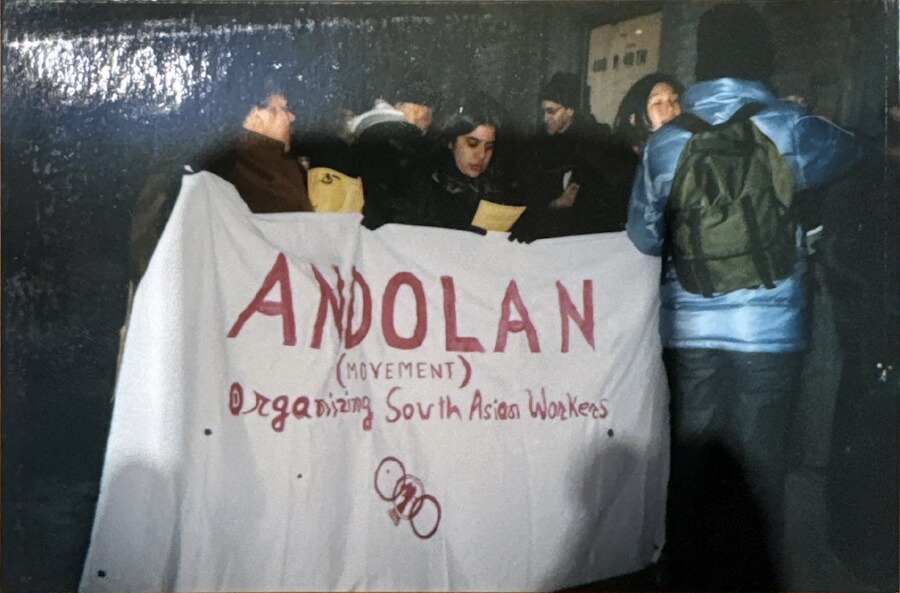

Nahar Alam created two organisations following the breakup of Sakhi: Workers’ Awaaz in 1996 and Andolan in 1998 (Gupta 2006). Alam, a former domestic worker herself and a member of Sakhi’s DWC, founded both to “bring public attention to cases on the federal violation of state minimum wages, sexual harassment, assault, and imprisonment upon false charges by employers” (Hossain 2023).

“Based in New York, this organisation is the first that is committed to directly challenging class inequities faced by the growing numbers of unorganised immigrant South Asian workers, a news release said. Workers’ Awaaz was originally the Domestic Workers’ Committee of Sakhi for South Asian Women…In its first victory, Workers’ Awaaz achieved a settlement with an ex-employer of a South Asian domestic worker in which the female worker received $20,000 in a federal lawsuit” (Desi Talk 1997).

Workers’ Awaaz’s mission statement centred class divisions. It instituted a rule that each committee would have at least half domestic workers, ensuring that their voices were centred in labour discussions. Alam noted the difficulty of organising on the behalf of domestic workers: they were largely “invisible” and out of the public eye, making it difficult for their abuses to be seen in the public sphere. Their conditions were brutal, working “up to fourteen hours per day…. completely dependent on their employers for food and shelter, and isolated from community members” (Alam 1997).

Andolan was created in 1998 “by and for low-wage South Asian women workers to support each other and to organise against exploitative work conditions” (Andolan records). Though Andolan’s main focus was on South Asian domestic workers, the organisation’s members consisted of a diverse set of occupations like babysitters, nannies, housekeepers, and those working in laundromats, garment factories, and retail stores where many South Asian immigrants found work…its focus (was) on placing power in the hands of workers to make decisions about campaigns, protests, and strategies to combat problems within the domestic worker industry.

Andolan, learning from past disputes, decided to keep “50 percent on each of its committees” as domestic workers …The creation of Andolan and the preceding debates about who should lead organisations for domestic workers shows the development of class consciousness amidst rapidly changing immigration patterns in the US.

Fighting back

The centre of a New York Times article noted in bold, black letters how South Asian domestic worker organisations relied on a common American tactic to fight abuse: “A Bangladeshi airs her grievance the American way: in court” (New York Times 2006). In the diaspora—even with the non-existent legal protections afforded by the National Labor Relations Act and Fair Labor Standards Act—and employers who refused to follow contracts, these organisations kept fighting. They used New York State minimum wage laws to gain lost wages, even for undocumented workers. They pursued legal aid claims in federal district court on the behalf of workers, organised protests outside the homes of employers, and led workshops to educate workers on their rights. Their work was vital, as they filled in for “a lack of formal union representation for domestic workers”(Human Rights Watch 2001).

Andolan led a number of legal proceedings that fought theft and indentured servitude for workers against abusive employers, often against the UN foreign diplomats. These settlements, ranging from $10,000 to $80,000, helped workers fight abusive employers and fought conditions of indentured servitude. These legal claims were novel for the time (Andolan records).

The existence of the organisations made workers more comfortable to pursue legal claims that they otherwise would have dismissed. Indeed, a worker from Bombay, India who worked for a South Asian family in the Upper East Side was paid $300 for a 150-hour week, never earning minimum wage or overtime hours. Initial hesitancy at pursuing a legal claim against the family was quelled by “encouragement from fellow workers at Andolan,” after which a lawsuit was filed on her behalf. Andolan also picketed on her behalf, holding up signs reading “Mr. Bhati, shame on you” and “slavery was abolished in the US” (Andolan records).

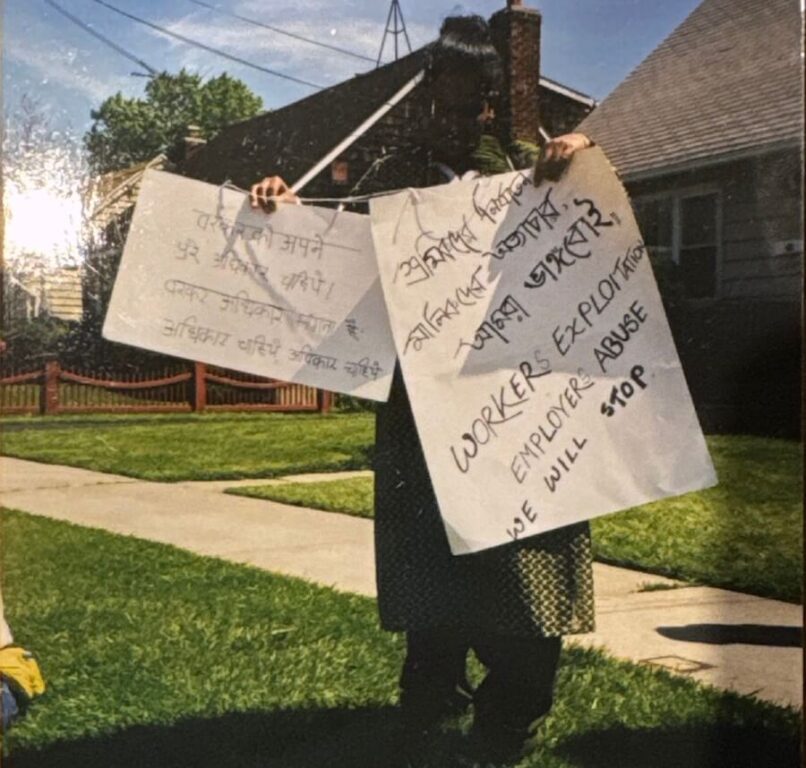

Organisations also led protests outside the homes of employers. This involved going to the suburbs and picketing outside of homes. They held signs that read “Stop Stealing” in both English and Bengali, a common South Asian language that many domestic workers spoke. The hypervisibility of protest contrasted with not only the private nature of domestic work, which is often viewed as invisible, but also the lack of attention paid to the abuse. This protest strategy was “crucial for naming the site of exploitation and recasting home and household as spaces of wage labor”(Varghese 2013).

By showing how labour inside the home deserved the same respect and protection as other work, domestic worker organisations reframed what household work meant…(they) also held educational sessions to help domestic workers become aware of the labour laws that did protect them. Despite not being citizens or federal protections, domestic workers still had rights like “minimum wage, overtime payment, meal breaks, one free day per week, disability insurance/workers compensation, and safe and clean working conditions” (Alam 1997). Workers’ Awaaz outreach was extensive: “on the subway, in the park, at schools, or when one of our members sees a South Asian woman with a different colour baby, we ask them who they are, what they are doing, if they have problems or know of another worker who has problems” (Dalal 1998).

Geneva and the NY bill victories

Central to Andolan’s work was their Diplomatic Immunity Campaign, which sought to protect abused domestic workers by challenging claims of immunity against diplomats in court. On December 12, 2004, Andolan was invited to participate in the 62nd United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva to “articulate international policy changes that should happen for the diplomatic immunity campaign.”Andolan formalised its concerns in a written statement to the UN Economic and Social Council. The joint statement, written with Global Rights and American Civil Liberties Union, highlighted the human rights abuses faced by domestic workers and the international community’s recognition of domestic workers as an “urgent human rights issue” (Andolan records).

The report notes it is “deplorable” that “the United Nations’ own staff… are still suffering exploitation and being denied their human rights” (Andolan records) …Its recommendations include written contracts for migrant domestic workers, a ratification of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, and asking the UN to support recommendations for international organisations to adopt codes of conduct for migrant workers.

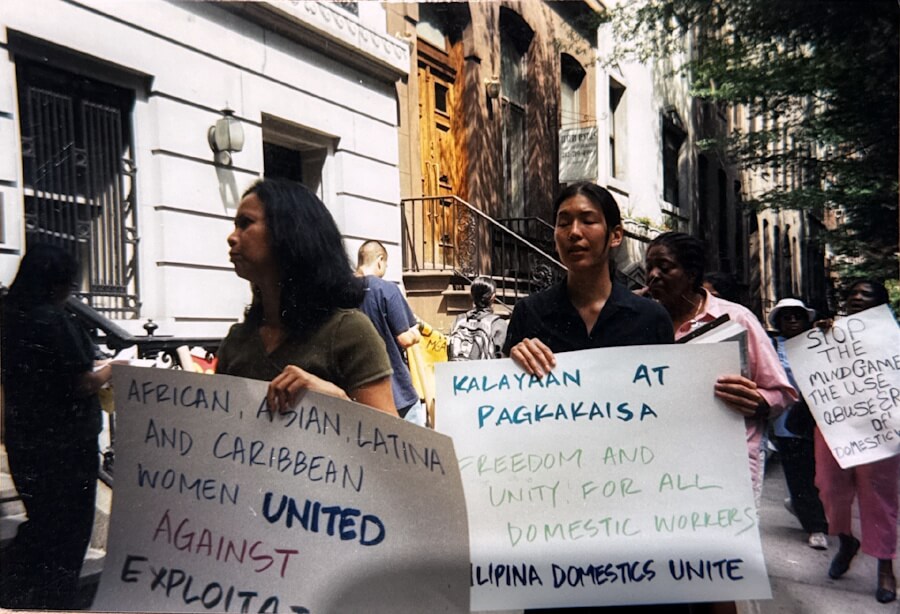

On August 31, 2010, the New York Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights was signed into law, the country’s first national bill of rights dedicated to the labour rights of domestic workers (Domestic Workers United 2000). The effort was led by Domestic Workers United (DWU), which was formed in 2000 by organisers from the Committee Against Asian American Violence (CAAAV) and Andolan (Domestic Workers United 2000). The law extended overtime pay after 40 hours of work per week, sick days, and rest days to domestic workers. It protected over 2,00,000 domestic workers previously excluded from labour laws in the US, marking a major victory for the domestic worker movement in New York.

Andolan, as part of DWU, reached across racial lines to collaborate with organisations like Adhikaar for Human Rights, Unity Housecleaners, Damayan Migrant Workers Association, and Haitian Women for Haitian Refugees over a decade to help pass the bill. Moreover, they testified over 40 times in six years in front of lawmakers in Albany, New York, stressing the lack of adequate legal protections in the industry (Poo 2011). Central to their messaging was explaining that domestic work, often perceived as invisible, was “real work” deserving of labour protections. Supporters of the bill carried signs reading “Tell Dem Slavery Done.”

The references to slavery, as I argued elsewhere, were crucial at pointing out historical injustices associated with domestic work and struck a chord with legislators. Governor David Patterson declared, as he signed the bill, “Today we correct a historic injustice by granting those who care for the elderly, raise our children, and clean our homes the same essential rights to which all workers should be entitled”(Glaser 2023). The passage of the 2010 Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights marked a significant victory for not just the domestic worker movement but also the South Asian community in New York.

South Asian domestic worker organisations had responded to exploitation and abuse with activism and advocacy, using legal aid mechanisms amidst a legal framework in the US that previously excluded domestic workers from labour protections. The arc of the South Asian domestic worker organisations has shown how, amidst living in a new country, South Asian individuals were simultaneously holding on to South Asian cultural ideals while using American systems like the law and courts to fight abuse.

References:

- “No Longer Silent,” Sunday Record, May 28, 2000. Box 2, Folder 12. Andolan (Organizing South Asian Workers) Records.

- Shamita Das Dasgupta, “Is All Well With Domestic Violence Work in the United States?” South Asian Magazine for Action & Reflection (SAMAR), Spring/Summer 1999.

- Diditi Mitra, Rotating Lives: Indian Cabbies in New York City, 2003.

- Sunil Bhatia and Anjali Ram, South Asian Immigration to United States: A Brief History Within the Context of Race, Politics, and Identity (2018).

- “Winter 1992,” South Asian Magazine for Action & Reflection (SAMAR), December 1992.

- DasGupta, Charting the Course: An Overview of Domestic Violence in the South Asian Community in the United States, 181.

- Margaret Abraham, Speaking the Unspeakable: Marital Violence Among South Asian Immigrants in the United States. Choice Reviews Online 38, no. 03 (November 1, 2000): 38–1851.

- Monisha Das Gupta, Unruly Immigrants. Duke University Press eBooks, 2006., 119

- Premilla Nadasen, Household Workers Unite: The Untold Story of African American Women Who Built a Movement, 2015.

- https://openlibrary.org/books/OL26884498M/Household_workers_unite, 151. 30 Ibid, 155.

- Linta Varghese, Looking Home, 160.

- “Frightened by threats, many abused workers stay mum,” Daily News, February 9, 1997. Box 2, Folder 13, Andolan (Organizing South Asian Workers) Records.

- Anaga Dalal, “Cleaning up Exploitation,” Women Organizing Worldwide, March/April 1998, Box 2, Andolan (Organizing South Asian Workers) Records.

- DasGupta, Charting the Course: An Overview of Domestic Violence in the South Asian Community in the United States, 180.

- Sangay K Mishra, Desis Divided: The Political Lives of South Asian Americans, 2016.

- Athima Chansanchai, “Maid in the U.S.A,” The Village Voice, Oct 07, 1997, (accessed February 17, 2025).

- Sharmin Hossain, “A Tale of Two South Asian Americas — Jamhoor.” Jamhoor, February 10, 2023.

- “Women Workers Organized,” Desi Talk, September 5, 1997. Box 2, Folder 12. Andolan (Organizing South Asian Workers) Records.

- Nahar Alam, “Domestic Workers Do Their Homework,” South Asian Magazine for Action & Reflection (SAMAR), Summer/Fall 1997,

- Pamphlet on Andolan’s Mission Statement, Box 5, Folder 1. Andolan (Organizing South Asian Workers) Records.

- “Suit Challenges Diplomatic Immunity,” New York Times, January 12, 2006, Box 2, Folder 12. Andolan (Organizing South Asian Workers) Records.

- “Hidden in the Home: Abuse of Domestic Workers,” Human Rights Watch., 29.

- Press Release, “Media Advisory,” Box 4, Folder 15. Andolan (Organizing South Asian Workers) Records.

- Nahar Alam, “Domestic Workers Do Their Homework,” South Asian Magazine for Action & Reflection (SAMAR), Summer/Fall 1997,

- Andolan Diplomatic Immunity Campaigns Media Packet, Box 7, Folder 14. Andolan (Organizing South Asian Workers) Records.

- “History — Domestic Workers United,” Domestic Workers United.

- Ai-Jen Poo, A Twenty-First Century Organizing Model, New Labor Forum 20, no. 1 (February 1, 2011): 51–55, 54.

- Alana Lee Glaser, Solidarity and Care: Domestic Worker Activism in New York City. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2023. Accessed April 9, 2025. ProQuest Ebook Central, 93.

Ashwin Marathe is a senior at Columbia University studying history and political science. He has developed intellectual interests in criminal justice, labour activism, and legal advocacy. His senior thesis seminar advisor was Professor Michael Stanislawski and second reader was Professor Isabel Huacuja Alonso at the Department of History, Columbia University.

Photos: Ashwin Marathe