Somewhere in the centre of Mumbai, not far from the ultra-posh Bandra Kurla Complex and chaotic-grungy Dharavi lies the Maharashtra Nature Park (MNP). This surprisingly quiet space amidst the city’s cacophony and hustle is a veritable treasure trove of trees. If you include the mangrove marshes not far away, at the confluence of Mithi river and the Arabian Sea, then this stretch of green helps Mumbaikars discover not only the beauty but also the significance of trees in a city that’s losing its green cover.[1]

In the MNP, established in 1994 as a botanical garden, illustrator and writer Abhishek Khan conducts fragrance walks of trees allowing trees to guide him towards the themes of the walks whether in Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Heritage Botanical Udyan and Zoo, also called Rani Bagh or MNP. This walk, which QoC’s Nikeita Saraf and I joined, was intriguingly called ‘The Botany of Witchcraft’. After three hours, we came away blown by the trees of Mumbai and the sheer wealth they have to offer. If only Mumbaikars cared to look closely, if only the authorities cared enough to protect this natural wealth.

Inside the MNP, the air is cleaner after the haze we breathed through to get here. Trees help to clean pollutants. The walk starts with Khan talking about the advent of botanical gardens as a coloniser project. They were set up by pillaging and plundering natural areas to remove native species and treating trees as “embellishments, considered cute decorations. Colonialism put plants into boxes”.

Trees, we reaffirm to ourselves on the walk, are not ‘the other’ but are a part of our city life. Trees and plants have thrived independent of people and, in fact, have sustained us. Those who recognise this thread in the web of life, know the trees and plants, the unique character of each, and their multiple uses. We need more tree walks for all kinds of Mumbaikars.

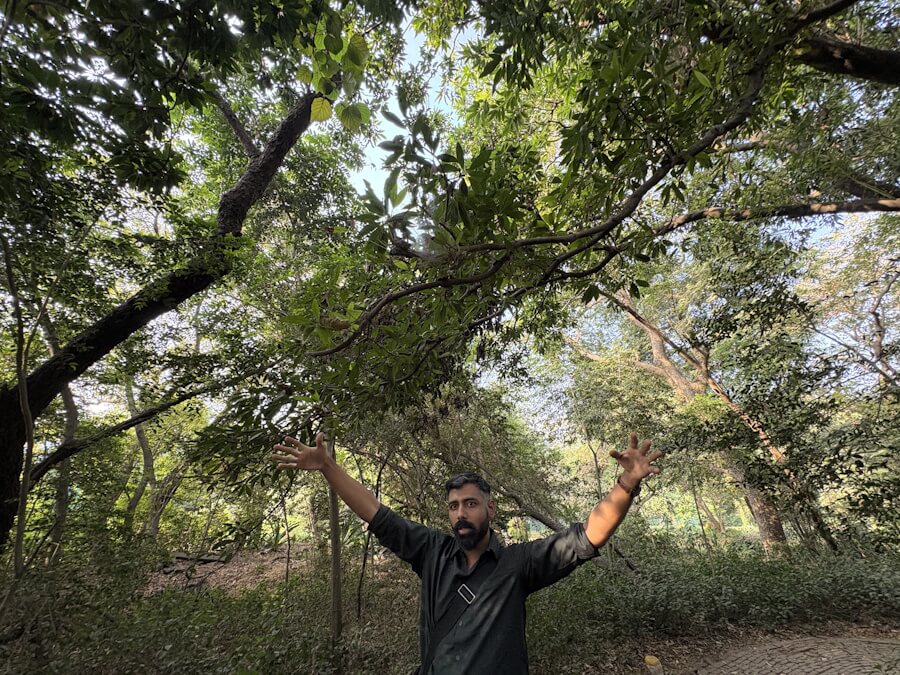

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

‘Botany of witchcraft’

One of the first plants we meet is the Passiflora Incarnata or Purple passion flower which is locally called Krishna kamal. Khan shows us how, if done the right way, one can get high off it. Right behind it is the Indian gooseberry (Emblica ribes) or the common amla whose seeds, he tells us, are burnt like incense to keep mosquitoes away by some communities. The Arjun tree (Terminalia arjuna) is a rare one that travelled from Ayurveda into science; it’s used in cardiovascular medicine and as an aphrodisiac for males, he adds. The Putranjiva tree (Drypetes roxburghii) was used as a fertility improver for women to bear sons. Is nature sexist or botany? The Sweet Apple (Annona squamosa), or what we know as Sitaphal, though has been mentioned in our scriptures, is not indigenous, Khan says, adding that it’s reportedly used in abortions.

Then, we come to the Elm Tree (Ulmus)associated with witchcraft the world over; shamans apparently talk to plant spirits and this tree ranks high for them. We then encounter the two-leaf nightshade. Brinjal, potato, tomato, tobacco and the datura (Datura innoxia) belong to this family and could be hallucinogenic. Khan talks about English women who used such plants as poison and midwives who administered their extracts as gynaecological “treatment” to induce abortion. This information, Khan says, was passed down orally as poems. He reads out one called the Girls Skipping Rhyme to us, the tree walkers.

“I have a deadly nightshade

So twisted does it grow

with berries black as midnight

And a skull as white as snow

The vicar’s cocky young son

Came to drink my tea

He touched me without asking

now he’s buried ‘neath a tree”

Listening to a poem about a tree inside a forest in Mumbai is a luxury, I reckon taking in the coconut palms. This too is a foreign tree, having floated here from the Malay peninsula, Khan tells us, but is found in the earliest legends of Mumbai when it was still an archipelago of fishing villages. The stories around trees are fascinating – Kerala’s toddy tappers were ostracised because people believed back then that they practised black magic, a poor woman heard crows on trees where she lived and knew guests were on their way to her shack. Such native knowledge, barely documented, is fast vanishing.

Photo: Nikeita Saraf

The fragrance and the taste

Surrounded by tall and short trees, canopies of plants and shrubs in a mind-boggling array of green hues, we walk on leaf litter. Khan picks up a leaf, carefully wipes and tears into parts, hands us each a piece. We take in a familiar fragrance and guess it as cinnamon, bay leaf or mace. Khan tells us it is Allspice (Pimenta dioica) whose fruits are sun-dried, ground into powder that’s sold in packs in supermarkets. We learn that such plants, in addition to not being native, are also dioecious which means they have separate male and female varieties and only the latter produce fruit.

We reach the tamarind trees. The Arabs apparently tasted it and called it tamar in their tongue, which was morphed into tamar-e-hind, and later was anglicised to tamarind, Khan tells us, handing us a leaf each to chew on. It tastes tart, of course, but also has a salty aftertaste. The variant with smaller leaves means it requires less energy to replace its leaves. The wonders of the plant world never cease, I think. The leaves of Shampoo ginger, or Insulin plant (Zingiber zerumbet), taste like grapes and the wild betel leaves are spicier than at the corner paan shop.

There’s a dead tree with black fungus. I dismiss it but I learn the power it holds – it’s the coal fungus (Daldinia concentrica) used to transport fire.[2] Then, we meet the Pongam tree (Pongamia pinnata) whose oil is used to light lamps, the Sheesham or Indian Rosewood (Dalbergia sissoo) which is reportedly not labelled to save it from poachers – its timber is greatly sought after to manufacture guitars – and the Fishtail palm (Caryota urens) with its serrated leaves used to make toddy. The Silk Cotton tree (Ceiba pentandra) is used by bees to build hives because its spikes prevent predators and then we see the Kumkum phal (Mallotus philippensis) which was the original tree used for kumkum or sindoor.

Photos: Jashvitha Dhagey

The wealth that’s trees

We then see Cinnamon (Cinnamomum) which has been eaten by insects and the Khus (Chrysopogon zizanioides) that’s popular across India for its cooling properties. There’s the Chikoo tree (Manilkara zapota) which too, Khan says, is not native but was brought from South America. Its sap was used to make chewing gum and ‘Chicklets’ of my childhood. Then we come upon the Sea poison tree (Barringtonia asiatica), found in a row along Marine Drive that were once used to literally ‘poison’ or immobilise the fish for a catch. With fishing nets and deep-sea trawlers, the trees have little use now.

On the opposite side is a tree with a rich history. The ubiquitous Ice Apple (Borassus flabellifer), or Tadgola widely available in Mumbai’s markets, a source of toddy, had a significant role in the development of the written word especially in south India; its leaves were the first to be used as parchment marking the transition from oral to written communication, Khan tells us. The leaves would, however, tear with vertical strokes which is why southern languages have rounded scripts, we learn.

Photo: Nikeita Saraf

Khan slips in an important fact that we file away: Leaf litter is not unclean, it helps retain soil moisture, enhances percolation, allows for more transpiration, and helps reduce the temperature. Clearing leaf litter, he says, is a part of the colonial legacy of pruned botanical gardens. The obsession with concretising spaces around trees means rain water is channelised out rather than allowed to percolate. As he speaks, the role of trees in preventing or minimising heat waves and floods is underscored.

Then, we see the fallen tree. It’s growing sideways, this Silk Cotton. “It has fallen but its roots are intact,” shows Khan telling us about how trees display gravitropism and phototropism which helps them survive.[3] The fallen tree could develop roots because it could communicate through the Mycorrhizal fungi with more of its kind – a community of trees.[4]

We walked into a Ficus grove. The Ficus family includes Cluster fig or Umber (Ficus racemosa), Banyan (Ficus benghalensis), and Peepal (Ficus religiosa). It is known as the ‘kickstarter species’ because birds love and pollinate it, making it grow faster. These are also called ‘walking trees’ because they seem to be moving as they braid with themselves. These ‘grow out of thin air’, remarks Khan, showing up in building crevices and wall cracks in cities.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Tree of life

The Tree of Life, a powerful symbol in several cultures, is represented in India through the Mahua (Madhuca longifolia) and is also imbued with references to Adivasi cultures in central India, Khan says. The toddy or spirit made out of Mahua continues to remain outlawed since the colonial era. The Mahua tree helped Indians survive two famines, Khan reminds us.

There is another Tree of Life prominent on Mumbai’s landscape – the Baobab (Adansonia digitata). It was apparently brought here by Africans when they were shipped as slaves and is found growing close to churches, Khan tells us adding that many Baobabs exist in SEEPZ. It grows in segments with older segments retaining even lakhs of litres of water, fruits and leaves are consumed, and its oil is used in cosmetics. The Baobab, also called ‘living fossil’ because it lasts hundreds of years, became associated with Hinduism when saint Gorakhnath gained enlightenment under it and began to be called Gorakh chinch too; the Hinduisation meant that Africans could not come close to it anymore, Khan adds.

The Gulmohar tree (Delonix regia) shows up next with its buttress roots that grow at right angles. Brought from Madagascar, it’s now a part of Mumbai landscape. The Saptaparini tree (Alstonia scholaris), Khan points out, has fragrant flowers but it does not give the kind of shade that Gulmohar does. Its branches do not spread out, so it does not fall when it is restricted below the ground; this makes it popular in Mumbai’s urban landscape.

Trees with large canopies also have spread out root systems. “As above, so below,” says Khan, “We do not acknowledge the tree life that exists below ground. When trees don’t get space to spread themselves out because of the concrete, they fall down easily.” People rarely see trees as beings or ecosystems, often pruning them to tame them or restricting their space.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

The leaves of the Indian Teakwood (Tectona grandis), he says, are used by Mumbai’s indigenous Warlis to make the signature red dye for their art. Khan shows us, to paraphrase John Berger, a way of seeing: “There’s a contrast in how indigenous people and colonisers interacted with nature. While the Warlis, in their flat and geometric drawings captured the ecosystem of trees, replete with treescapes, wells, and people interacting with nature in their daily activities, the colonial drawings realistically captured textures and colours of specific plants for easier identification but this led to trees extracted out of their geography for display.”

Some trees grow in silos, like the Rain Tree (Samanea saman), without a network of their species. “It is an island in itself. Even ants don’t interact with it,” Khan informs. We then glance at the Tabebuia (Tabebuia rosea) with its pink flowers in full bloom. An ornamental tree, it apparently takes a lot of nutrition and does not interact with trees around it because it is not a native species. But then there’s the Black Pepper (Piper nigrum) which acclimatised to our conditions and brought colonial traders – and later, power.

And just like that, amidst a bounty of green, the tree walk comes to an end. It has given me a sense of the lush and leafy abundance that nature has to offer even in a concretised and densely built-up city like Mumbai. And, in the last clearing, I find an image of what the city must have looked like before it got its modern skyline – a lot of leaf litter, low fragrant notes, bursts of colour in different flowers, a smorgasbord of tree trunks, and quiet climbers and creepers all over. A forest as busy as the city would become.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Cover photo: Nikeita Saraf