There’s irony, there’s dark humour, and then, a muddle of the two. On July 31, a day after torrential rain and two massive landslides flattened villages, took hundreds of lives, and altered the course of streams in Wayanad district, Kerala, a draft was issued from New Delhi notifying ecologically-sensitive areas in the Western Ghats. It sought to regulate development activities in the Ghats which straddle 1,600 kilometres parallel to India’s western coast, across six states including Kerala. In the list of 13 villages notified as an eco-sensitive area (ESA), it included Noolpuzha which, like Mundakkai, Chooralmala and Attamala in Wayanad, was wiped off the map. The union Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, which issued the draft notification, has macabre timing.

The draft outlined 56,825 square kilometres of land across Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra and Gujarat as eco-sensitive – nearly 10,000 square kilometres in Kerala alone – and called for a ban on mining, quarrying, thermal power plants, new or expanded industries under certain categories, and regulations for new buildings and hydropower projects. This draft notification could have been – but was not – a serious response to the landslides that claimed more than 400 lives (the official toll is 225), left 150 people missing and vast tracts of land damaged.

It was merely the union government ticking off a box – replacing an expired draft with a fresh one. The previous draft lapsed on July 31; the ministry merely re-issued it that day. Over the past ten years, there have been five such drafts but none turned into law. The reason? States raised objections that the ecological restrictions would damage their economic potential and jobs. Hundreds dead and thousands displaced in Wayanad paid a heavy price for this, indeed.

This, in a nutshell, is India’s development story which wilfully ignores and overrides anything ecological. But it is a narrative that simply cannot hold any longer in the face of the exacerbating climate change impact that places both nature and people in harm’s way. Wayanad represents the wilful disregard of ecology or an ecosystem in which development is done, cities are built, infrastructure is made, and relentless construction carried out. Why only Wayanad, towns and small cities in hilly regions of Uttarakhand to Himachal Pradesh, Dehradun to Malana, show that this is no longer sustainable.

To see Wayanad as a great disaster after which life – and construction – can go back to business-as-usual would mean writing more such or similar disasters into India’s development story. The lessons from Wayanad are many – for hilly regions as well as for India’s cities.

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf

Known dangers ignored

Development is now a euphemism for more and more construction of all types. When this is undertaken in eco-sensitive areas, with no regard to the local ecology, there can be only one inference: A powerful nexus of vested interests from governments to private corporations enable or manufacture ecological disasters such as landslides, flooding, and heat waves. These can no longer be called natural disasters given the large footprint of human decisions or interventions that enable them. In fact, they are being manufactured with every licence issued to quarry, mine, and construct.

The Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel, chaired by ecologist Professor Madhav Gadgil, in 2011, had suggested three ecologically-sensitive zones – ESZ 1, ESZ 2, ESZ 3 – along the Ghats with differing regulations for each. It had sought to protect nearly 64 percent of the Western Ghats across the six states. The report categorised all of Wayanad’s talukas as ‘ESZ I’ which meant the most stringent regulations, including a ban on construction and mining. Prof Gadgil recently termed the Wayanad landslides in the highly eco-sensitive area as “man-made”.[1] As is well known, the recommendations were rejected or disregarded by all states.

The government then set up the Dr K Kasturirangan Committee which diluted this to considerable extent but still kept around 37 percent of the Western Ghats out of bounds for development. Even this report was disregarded. Successive union governments have been content to periodically issue draft notifications, like the one of July 31, with no real intent to secure and conserve ecologically-sensitive areas. The Western Ghats, a unique biodiversity hotspot with 325 rare species, was given the status of the UNESCO World Heritage site in 2012[2], a year after the Gadgil panel report was virtually rejected.

But this is not only about Wayanad or the Western Ghats. How India’s governments plan and locate major and minor projects in hilly areas across the country and in its cities and towns will determine the sustainability of places as well as the security of people. Hill ranges in Assam and Uttarakhand to the Aravallis, the Himalayan states and, of course, the Western Ghats are all facing enormous anthropogenic pressure – human factors and decisions that disrupt, destroy and devastate the ecology.

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf

Torrential rain, cloudbursts, flash floods and landslides ripped through places and people across India, in fact across Asia, this June-July. Shimla, Kullu and Mandi districts in Himachal Pradesh were wracked by heavy rainfall and flash floods that led to 15 deaths, 87 roads closed, 41 transformers and 66 water supply schemes disrupted including the Malana power project, and losses of over Rs 662 crore. Karnataka’s Ankola district saw massive landslides.[3] Joshimath and other towns in Uttarakhand have seen rain-related havoc.[4] Pune and surrounding areas were inundated for days as roads and bridges disappeared under water, its hills threatened by increasing construction, and its river banks seeing construction as part of the riverfront ‘development’ project.[5]

The Western Ghats, whose eco-sensitivity has been well established and internationally recognised, are seen as fair game for ‘development’ or demolition-and-construction. Every road built through mountain ranges, every tourist resort built atop hills, every mining pit and quarrying site in the natural elevation, every project that received ‘environmental clearance’ has meant that an ecological disaster has been manufactured. Similarly in cities and towns across India. Roads cut through forested areas, trees hacked for buildings, rivers and streams bent for infrastructure, open areas colonised for large complexes mean disasters are manufactured as cities are built.

Hard lessons from Wayanad

Flooding and landslides hold many lessons if we, rather our governments and corporate houses, are willing to pay attention without dismissing ecological talk as namby-pamby and ridiculing environmentalists as hindrance-creating busybodies.

First, all and any digging into mountains, hill ranges, or deep into a city’s floor, because it can be done, turns hazardous in the long run. Just as Wayanad’s hills were blasted and drilled into for roads and resorts, the earth in India’s cities and towns is dug deep to hold tall towers, to create basements that go four and five floors below ground as parking spaces for hundreds of cars. The unsustainability of this path of ‘development’ was laid bare in Wayanad; it is brought home every monsoon in our cities from Delhi to Mumbai, Bengaluru and Pune where cars float in heavily-inundated areas.

Photo: Murali via X

Second, land use and land cover changes cannot be made at the pleasure or persuasion of a few vested interests or powerful lobbies such as real estate developers. Their aim is to maximise profits, not conserve ecology. It is for elected governments and bureaucrats, as custodians of natural areas, to ensure that such powerful interests do not undermine the ecology at the local, regional or state levels. Why, for example, did the Maharashtra government allow builders to construct on every inch of a plot without leaving ground space for trees and rainwater?

In Wayanad, land use changes meant resorts and hotels for tourists were situated deep in forests or high on hills – to make them exclusive – with the face of a hill cut for roads; land use changes also meant quarrying permits and mining licences, and a shift from self-sustaining agriculture to real estate-based local economies. This study[6] showed that in only one taluka of Wayanad, Vythiri, the “built-up area and grassland increased by 19 percent (115 square kilometres) and 25 percent while agricultural land and barren land decreased by 7 percent and 15 percent respectively”.

Third, ecological elements like forests and water have been viewed as fair game for exploitation by people for their profit or pleasure. This precludes the idea that natural areas are valuable for their own sake and, in fact, have complex ecosystems that cannot carry price tags. Wayanad, as other disasters before it, teaches that natural areas must be respected so that, even after construction, there are spaces left for water, trees, and a vast array of biodiverse species. As environmental economist Dr Pavan Sukhdev said at the Darryl D’monte Memorial lecture last year, “nature does not send us an invoice” so we do not ever know the full cost of any built space.

Mumbai’s underground metro 3, for example, was built at a whopping Rs 37,276 crore but even this does not include the value of more than 2,200 trees chopped down in the Aarey forest for its car depot or the value of the biodiversity they supported. The Char Dham road project in the fragile hill region in Uttarakhand, connecting pilgrimage towns of Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri, and Yamunotri with 53 civil works across nearly 890 kilometres of hills, is estimated to cost Rs 12,000 crore. What is the true and complete cost of boring deep into the Himalayan ranges?

Four, tree plantation cannot be a politician’s photo-op in which people who are not arborists or botanists decide, in their limited wisdom, which trees are to be planted or transplanted and where. Wayanad saw a large area of its hill slopes with naturally-growing vegetation replaced with mono-culture crops such as rubber or non-native trees planted for decorative purposes. The rubber trees could not hold back water in the soil; some native trees held out better.

Five, parse the scientific studies, listen to the experts, respect their recommendations, and then make them the basis of development plans. For towns and cities to thrive, in the hills or plains or sea coasts, master plans will have to make space for ecology; in fact, all planning must be nature-led or nature-based. Every natural ecosystem has an inherent carrying capacity beyond which it will push back in what we see as disasters. Climate change has worsened many of these as rainfall patterns have changed, drier areas have intense rainfall, four-month monsoon areas get short bursts of intense rain, heat waves have travelled to the hills with towns there showing summer temperatures of 38-40 degrees Celsius, and so on.

Photo: Tushar Sarode/Wikimedia Commons

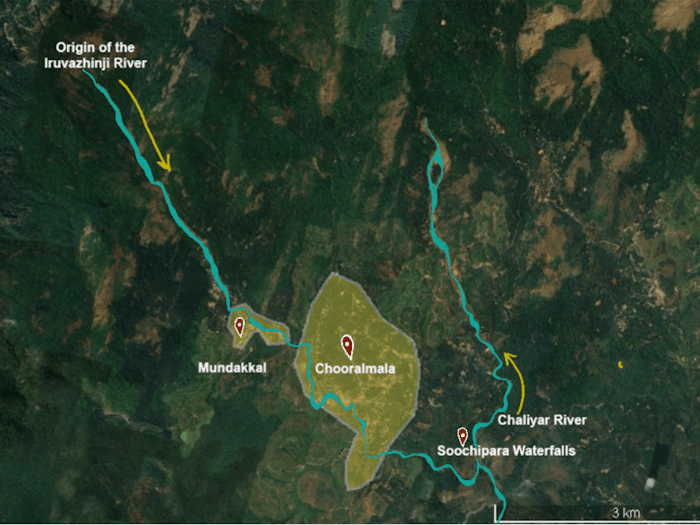

Wayanad, for example, received a staggering 572 millimetres of rain in 48 hours preceding the landslides – above the normal. Scientists studying the subject have also ascribed the landslide disaster to the climate change factors.[7] [8] The intense rainfall triggered landslides which, together, pushed an astonishing 86,000 square metres of land down the hill slopes, as seen in the high-resolution images of the National Remote Sensing Centre. No village and no construction in its runout stood a chance; most of the plantation labourers and workers did not either. In Himachal Pradesh, Assam, Delhi, Mumbai, rainfall has breached its normal records and patterns.

However, to only fault climate change and discount human decisions, the anthropogenic factors, is to invite exacerbated disasters. Climate change is not an unknown science. To continue to bend nature, control and colonise it, and pretend that development or construction can continue the old way is catastrophic. To draw up master plans for regions or cities in an ecological vacuum is no longer sustainable but an invitation to climate-related disasters. Indeed, disaster management has come a long way in the past three decades but, however finely-tuned and responsive, mere management of disasters such as cloudbursts, flash floods, landslides, and heat waves is out of step with what is needed now.

Wayanad’s disaster should force a review of development plans, both in that district and across India’s cities and towns, to build in nature – not at the cost of nature.

Cover photo: Akhin Sreedhar