Monsoon in India has become synonymous with extreme rainfall leading to flash floods, waterlogging, landslides, and cyclones on a scale probably not experienced before. India’s cities and villages lurch from one disaster to another as the impact of climate change plays out. Is the monsoon changing? Is it changing differently in different places across the country? Should authorities be paying more attention to this aspect than they have for flood-preparedness?

‘Decoding India’s Changing Monsoon Patterns,’ a tehsil-level assessment that examined India’s monsoons between 1982 and 2022 and analysed the shift in rainfall patterns, was released earlier this year by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).[1] The team studied the southwest and northeast monsoons and found that:

- 23 percent of India’s districts witnessed rainfall extremes with a high number of deficient and excessive rainfall years

- The last decade saw significant changes in the form of rainfall increase, deficit, and intensity

- 55 percent of India’s tehsils saw an increase in the southwest monsoon rainfall between June and September in the past ten years

- 11 percent of tehsils in the ecologically sensitive areas of the northeast and the Himalayan range saw a decrease in rainfall in only the last decade

- 64 percent of the tehsils saw an increase in the frequency of heavy rainfall days by 1-15 days per year in ten years compared to the previous 30

- The proportion of total seasonal rainfall between June and September is on the rise too

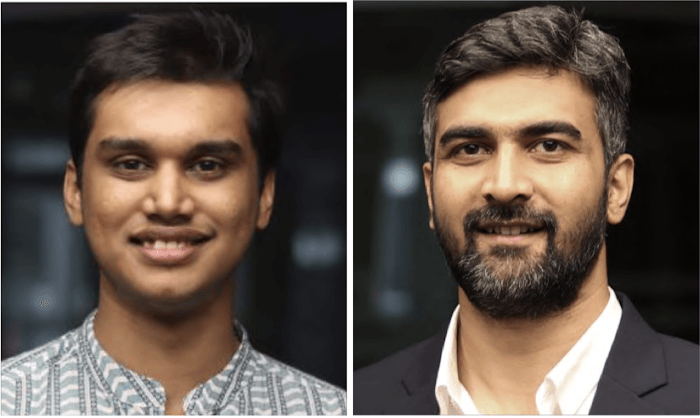

Programme Associate Shravan Prabhu and Vishwas Chitale, Lead, Climate Resilience team at CEEW, recommend local level plans for rainfall including granular mapping of risks and vulnerabilities, and early warning systems. In a pattern that can be attributed to evolving rainfall, they observe in a previous study[2] that nearly 40 percent of districts in India show a “swapping pattern, alternating between drought and floods, which leads to compounding risk.” Another study published in 2021 found that more than 80 percent of India’s population lives in districts that are highly vulnerable to extreme hydro-met disasters.[3]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The changing monsoon is reflected in this year’s season. After a timely onset, it was a dry June in most parts of the country. Then, there was excess rain in parts of the country while areas in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, and Jammu-Kashmir remained dry, writes Earth Systems Scientist Raghu Murtugudde.[4] The State of the Environment report, by the Centre for Science and Environment, found that extreme weather events were reported through all 122 days of India’s monsoon period between June and September last year.[5] This 2023 study[6] highlighted “frequent hydro-meteorological extreme events and climate vulnerability concerns.” It noted that the number of extreme rainfall events had increased in recent decades and called for real-time predictions for proactive disaster management.

Rainfall trend in cities

Cities have taken some note of the changing monsoon in their climate action plans but not a complete assessment or preparedness to face it, based on Question of Cities’ reading of the plans.

The Mumbai Climate Action Plan, based on official decadal data, “reiterates the increasing frequency of very heavy and extremely heavy rainfall events in the city” highlighting that the city has fewer rain days but the total rainfall per season has increased.[7] Bengaluru’s Climate Action Plan notes higher chances for extreme events with greater possibilities of both wetter and drier periods.[8]

Delhi’s Heat Action Plan weighs in on how heat waves were largely caused by sparser pre-monsoon showers which brought less moisture than normal. “The sudden end of pre-monsoon rain showers, an uncommon trend in India, has contributed to the heatwaves,” it states.[9]

The Ahmedabad Climate Action Plan observed that the city has fewer rain days while the annual rainfall increased by 12 millimetres per decade between 1970 and 2020.[10] The Climate Action Plan for Nagpur projects that the city will see an increase in rainfall by 12.5 to 30 percent and annual mean temperature by 1.95 to 2.2 degrees Celsius.[11] Bhopal’s plan shows an increase in rainfall average by 8 percent by 2050 and an increase in the number of heavy rainfall days by four days.[12]

Are cities aligning, or re-aligning, their monsoon preparedness and disaster management to account for this is an open question without clear answers.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

‘Normal’ monsoon and national average

The CEEW report points to unpredictable rainfall patterns that trigger severe floods in some cities while the traditional monsoon states face rainfall deficits. Last year, for example, about 50 hours of rain in Chandigarh was enough to fulfil near half of its annual rainfall quota[13] while this June saw Maharashtra and Kerala with 46 percent and 60 percent deficit respectively.

India’s varying terrain and weather conditions mean that monsoon patterns vary greatly. The study highlights this. The definition of a ‘normal’ monsoon at the country level is a national average of total rainfall received throughout the monsoon months but we need to also look at the spatial variability that causes changes in wet and dry spells, and extremes. The study infers that nearly 64 percent tehsils in the country experienced an increase in the frequency of heavy rainfall days while tehsils in Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and the western coast had more very heavy rainfall days between June and September.

The rise in the proportion of total seasonal rainfall between June and September could be one of the reasons behind the flash floods in Delhi, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh in 2022 and Bengaluru in 2023, the study points out. The 55 percent tehsils of India which witnessed an increase in southwest monsoon saw its intensity too increase by 10 percent compared to the June-September baseline. Some of these were, surprisingly, the traditionally drier tehsils in Rajasthan, Gujarat, central Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu. The dry Rajasthan, the study points out, had the highest excess rainfall in 2023 and 77 percent of tehsils in the state have been seeing increased rainfall over the past decade.

The changing monsoon patterns during winter also mean that parts of India have become vulnerable to forest fires. Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, northwestern Madhya Pradesh and parts of Vidarbha in Maharashtra are seeing a decline in the rainfall received between October and December; Uttarakhand leads the list with about 86 percent of tehsils facing this. The dryness is creating conditions that could cause frequent and intense forest fires. The southwest monsoon is withdrawing later than usual, bringing more than 10 percent higher rainfall in October to nearly half of India’s tehsils.

The report highlights, among other aspects, the importance of adopting newer frameworks that look at month-wise variability and contrasts between dry and wet extremes on a spatial scale. It underscores the need for district-level action plans based on socio-economic and sector-specific data, the necessity of hyper-local data at tehsil level to create ‘precise climate models and hyperlocal action plans’, and the importance of data democratisation by increasing weather recording stations to provide real-time micro-climate information.

In their own words

Researchers Shravan Prabhu and Vishwas Chitale of the CEEW took a few questions in this email conversation with Question of Cities.

Your report sounds several alarms about India’s changing monsoon. How should the findings be interpreted for cities?

Our findings suggest that while more than half of India’s tehsils experienced an increase in southwest monsoon rainfall (June to September), over 64 percent also saw an increase in the frequency of heavy rainfall days between 2012 and 2022 compared to the climatic baseline of 1982-2011. This indicates that the increase in total rainfall is primarily due to extreme rainfall.

Interestingly, the highest such increases were observed in traditionally arid or semi-arid regions such as Rajasthan and Gujarat, as well as on the western coast, which includes cities like Mumbai, Pune, and Mangalore. These cities have also experienced extreme rainfall this year. The erratic patterns of changing monsoons are visible. For instance, according to IMD data, Delhi saw nearly twice the normal rainfall for June in just one day on June 28.

These trends indicate that we need to prepare our cities for intense and prolonged heat waves in summer, followed by erratic rainfall characterised by very heavy downpours. This means we need to pay heed to early warning systems and climate proof our critical infrastructure.

Your research found that rainfall increased across the country but decreased over Indo-Gangetic plains, north- eastern India and Indian Himalayan region in the last decade. How will this play out?

The Indo-Gangetic plain is critical for our agricultural outputs. Our analysis indicates that while 11 percent of India’s tehsils experienced a decrease in southwest monsoon rainfall (June-September) between 2012 and 2022 compared to the climatic baseline 1982-2011, 87 percent of those tehsils showed a decline during the initial monsoon months of June and July, which are crucial for the sowing of kharif crops.

Moreover, in highly rainfed agricultural states such as Maharashtra, we found significant month-to-month variations in monsoon changes, such as a decrease in August rainfall in eastern parts and an increase in October rainfall. These trends pose significant risks to our agricultural systems, which means we need to reassess our strategies. For example, we should make cropping calendars climate-smart by providing week-by-week weather normals and advisories.

Photo: Ministry of Defence/Wikimedia Commons

What kind of policies do you think will help to prevent the incidence of disasters and hazards as a result of this study?

We need local-level plans that map risks from changing monsoons, especially for cities that face seasonal risks such as heatwaves in summer, urban flooding during monsoons, and air pollution in winter. Cities need to focus on developing extreme rainfall risk mitigation plans that address various aspects, including early warnings, preparedness before the monsoon season, immediate response, and long-term climate-resilient urban and infrastructure planning.

The CEEW has collaborated with the Thane Municipal Corporation to develop localised heat [14] and urban flooding action plans.[15] These plans feature a first-of-its-kind administrative ward-level mapping of heat and urban flooding risks through a comprehensive analysis of climate, socio-economic, and demographic datasets. The plan provides a framework for city administrators to prepare for and respond to urban floods and mitigate risks. To achieve this, it offers actionable and holistic recommendations for strengthening the city’s adaptive capacity, helping to transform Thane into a climate-resilient smart city.

Women and the marginalised are often the worst impacted by changes in climate patterns. What kind of provisions must our policies have to take them into account?

Extreme weather events do not impact everyone equally. People living in slum areas, women, marginalised communities, and those with pre-existing health conditions face heightened vulnerabilities, whether from extreme heat or heavy rains. Therefore, our local action plans must include granular mapping of risks and vulnerabilities that considers these factors. This approach will enable administrators to prioritise resources for the most vulnerable sections of the population.

How does one interpret India’s top four states for Gross Domestic Product – Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, and Karnataka – are seeing an increase in the frequency of heavy rainfall?

Extreme rainfall can lead to economic losses in these states, which puts our overall GDP at risk. Therefore, it is essential to climate-proof our economy.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award 2023, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Cover photo: Upvan Lake in Thane swells during heavy rainfall in 2018. Credit: Nikeita Saraf