“Be it acknowledged: The man-made environments which surround us reinforce conventional patriarchal definitions of women’s role in society and spatially imprint those sexist messages on our daughters and sons. They have conditioned us to an environmental myopia which limits our self-concepts…which limits our visions and choices for ways of living and working…which limits us by not providing the environments we need to support our autonomy or by barring our access to them.”

From Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics (1981)

As a student of architecture, my introduction to women in the field was through the late Zaha Hadid’s works. Her radical designs incorporating three-dimensional data sets, smooth curves and crisp white exteriors were awe-inspiring and aspirational. It wasn’t until Humanities was introduced that the class came upon the exhaustive catalogue of women practitioners who contributed, and continue to contribute, to city-making. The exclusion or non-importance of Gender Studies in architecture education manifests in the way cities are planned and built.

As Leslie Kerns writes in Feminist City, “women still experience the city through a set of barriers –- physical, social, economic and symbolic –- that shape their daily lives in ways that are (although not only) gendered”.

Though I was fortunate to study architecture in an institute that brought social equity and similar subjects into classrooms, I have had my own journey of learning about women who paved the way in architecture, planning, and spatial equity. From discovering the late Urmila Eulie Chowdhury’s work in designing Chandigarh, which is commonly attributed only to Le Corbusier, to learning about the late Pravina Mehta’s contribution to the New Bombay Development Plan in the 1960-70s, I realised that documentation, acknowledgement and recognition of women’s work in the field is lacklustre, if not absent.

However chequered the history, there is a tradition of women architects involved in planning and making of cities. This is evident in resources like Pioneering Women[1] and Her Perspective[2] but the documentation of South Asian practitioners is appalling. Women contribute to almost 50 percent of the population – and users – in city environments but are seldom part of its design, even women architects are few and far between. The few that work are rarely visible or heard. Only six women have won the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize, set up in 1979,[3] with Hadid being the first in 2004.[4]

As Jane Rendell points out,[5] where women’s spaces do exist, they are “primarily the result of activism by women, women’s movement organisations, and the work of those few but increasing feminists who are elected or appointed political office”. The default design is exclusionary of women and is an outcome of poor policies and unequal opportunities. This reinforces the gender stereotypes. There is growing evidence[6] that gender-based design has positive impacts on climate too, with reports[7] calling for integrated systems. Yet, the move to bring more women to the design table leaves much to desire.

Yet, lived experiences show that women planners and architects make cities that are better suited to all genders and, possibly, more sustainable in the era of climate change.

Over decades, collective efforts of women have led to participatory urban planning. Barcelona’s Plan for Gender Justice[8] is a blueprint for cities. By breaking down daily life into four aspects – productive, reproductive, community, and personal — it showed that urban design was “no neutral matter”. In New York, mayor Sadik-Khan pedestrianised over 180 acres of the city’s roads[9] and established a bike-sharing service to encourage walking and cycling as sustainable transport modes.

In the subcontinent, women architects have been quietly at work. Practitioners like Yasmeen Lari in Pakistan, Madhavi Desai and Neera Adarkar in India are some who merged architectural practice with social equity issues. Lari, widely considered Pakistan’s first woman architect, pioneered the country’s first housing programme, Angoori Bagh,[10] and designed a fuel-efficient chullah[11] to improve women’s health. Adarkar and Desai, both practitioners and veterans, are founder members of Women Architects Forum.[12] They have both authored books that focus on gender and cities.

The lens matters

It is only when the gender lens is applied to cities that the lack of equity, accessibility, inclusivity, amenities shows up. From the absence of bag hooks and trash cans in women’s toilets to grab handles in buses and trains at the average male height, it is easy to see how the non-application of the women’s lens manifests in everyday urban design. This ‘lack of’ narrative can sound like a grumble or grievance, but acknowledging it is important for all planners and architects, especially men who dominate the disciplines.

Despite this, women practitioners have made meaningful contributions in the last few decades. To redefine ‘practising architect’ especially for young practitioners, Gita Balakrishnan founded Ethos.[13] “While I forged my own path, I did not have to face issues that other women did. I don’t compromise easily and I make my voice heard…‘Negotiations’ in city-making usually mean compromise. You have to first include women in the process of evolving strategies,” she says. Start acknowledging that gender does not have much to do with capability to work on construction sites, the system has a huge role to play, she adds.

Anuradha Parmar, executive director of Urban Design Research Institute (UDRI), architect and urban planner, believes that “if you design for women or any minority, you make the space better for everyone”. Parmar has worked with public authorities as well as private institutions. She says, “The way we design our spaces controls the way people interact with those spaces. The key is that these interactions vary for men, women, children, senior citizens.” Gender-related inhibitions exist, especially in a country like ours, but the onus is on practitioners to start including women from the very first stage of design and planning, she adds. There is a growing need for safe, secure public spaces where women and girls can play, work and rest; the public space is a solution to “mitigating impacts from rising temperatures to harmful air quality to inequities facing our communities”.[14]

It is often remarked that women are naturally inclined to be better professionals due to stereotypical ‘feminine’ reasons but women architects have spoken out about sexism and unequal pay, besides other drawbacks, in the profession.[15] Jane Rendell did a deep dive[16] asking if women practised architecture differently and how these differences ultimately manifested in spaces.

Urban planner and policy analyst Dr Lalitha Kamath says, “Women are usually better listeners; they are partly socialised to do so, to take a background role rather than an assertive one. Women are good at navigating the politics of relationships and working collectively…the work spheres that women look at are different too as they tend to prioritise what they see is essential to life –- like water, sanitation and health.”

Deliberate action

American urban anthropologist Katrina Johnston-Zimmerman spends time in public spaces to understand how people use them in different ways. She founded the Women-Led Cities Initiative to bring women’s voices to the forefront of urban planning. “The future of our cities is female because it has to be. Without a greater level of diversity through women’s input and impact on our urban environments, we are at an impasse for the future of manufactured habitats,” she said in this BBC interview.[17] She advocates a shift in thinking for more humanist cities.

Building climate resilience, especially in the Global South, means ensuring that vulnerable groups like women, especially lower in the economic pyramid, are equipped to handle the inevitable adverse effects of climate change.[18] The long-term impact also affects a region’s access to basic services like water, increasing women’s work and risk. Women architects have paid closer attention to such issues.

Pune-based architect Pratima Joshi founded Shelter Associates to work on water and sanitation issues in the city’s slums. “When we started in 1993-94, talking about data and toilets was unheard of. There were very few women in the housing and sanitation space; it must have been uncomfortable, unrelatable and intimidating for many. Initially, men from the slum communities and government offices were not welcoming but we could easily connect to women in these communities. We recognised women as important decision-makers of their families,” she says.

An impactful project of Shelter Associates has been ‘One Home One Toilet’ created as a response to “women’s sanitation woes” with rigorous slum mapping and community mobilisation. It filled the gaps in Pune’s sanitation services; 27,500 families have been provided with toilets so far. “We have detailed household-level data of slum dwellers to correctly identify the gaps and prioritise resource allocation. It is important to include the marginalised communities in the deliberations and implementation…Our approach is to create a platform where urban local bodies and community members can have a sustained dialogue,” Joshi adds.

Interdisciplinary practices like Shehar Collective[19] that Dr Anu Sabhlok and Dr Kanchan Gandhi, of the Mohali-based Indian Institute of Science Education and Research are part of, explore small and medium cities in India. Says Dr Gandhi, “Citizens across genders have been bypassed in the selection and implementation of projects. In our country, political interference and elite capture are big issues which leave little room for participatory approaches. Urban agenda in India is largely elite driven.” This excludes women. In Abohar, Punjab, the organisation encourages students to conduct urban analyses of the town.

Gender-responsive planning and design

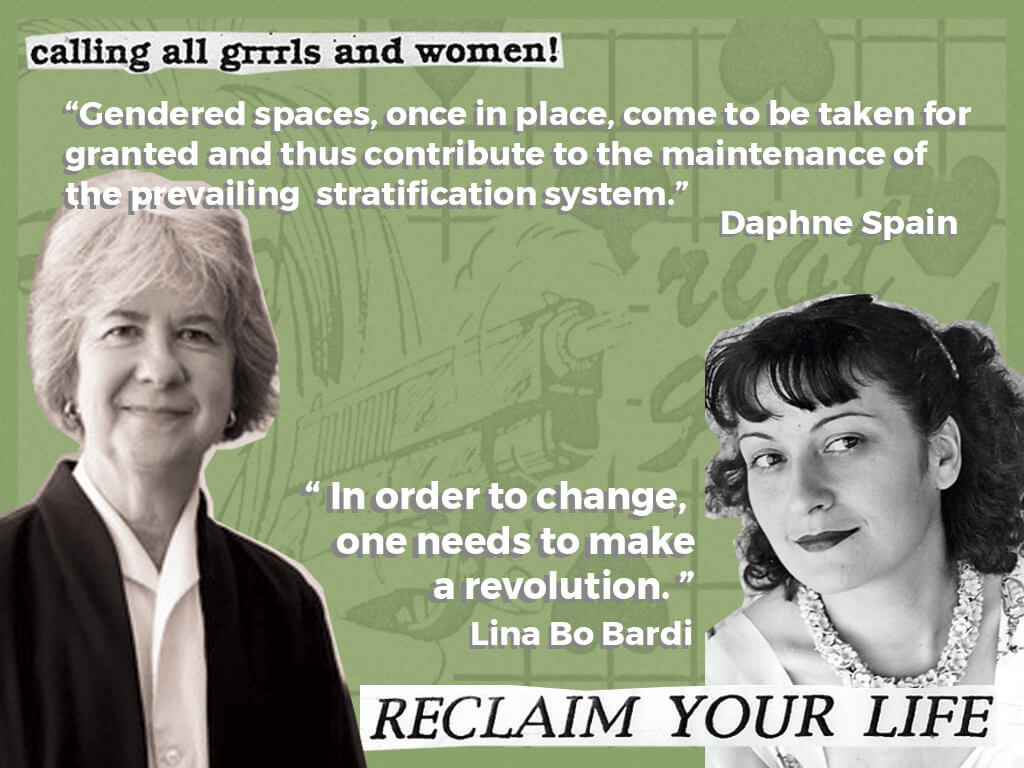

The discipline of Women’s Studies in the late 1950s was a response to the exclusion of women’s participation in and contribution to traditional academic disciplines; it eventually transformed into Gender Studies and found its way into urban design and planning too. Whether it has led to gender-responsive cities and spaces is an open question.

Johnston-Zimmerman, in her TedX talk,[20] makes a valuable distinction about designing a public space: “The problem in planning for everyone is that you run the risk of only planning for a few, based on who is doing the planning. Through implicit or explicit bias, you end up potentially excluding a lot of people”. The term ‘gender-inclusive cities’ is often heard but what does it mean when applied to urban spaces?

Women practitioners have pioneered and facilitated this discussion. Women in Urbanism,[21] a group advocating gender mainstreaming, believes that inclusive cities cannot simply mean street lighting or gender-balancing of names of public spaces; what is ‘gender-neutral’ usually has a male perspective, it states. By mapping gender inequalities in Brussels, it brings together professionals to develop gender-sensitive initiatives and amplifies voices that weren’t heard before in Brussels.

Gita Balakrishnan says there are many initiatives in India too but “the problem lies in all of us not coming together. It’s time to say ‘women in architecture’ instead of ‘women architects’ because we need to involve everybody including men.” Cities Alliance[22] seeks to develop policies, strengthen communities, and undertake city planning through an inclusive lens; its initiatives like Women and Sustainable Cities programme, partnering with local governments and feminist organisations (Figuig in Morocco, Kairouan in Tunisia, Sebkha in Mauritania) bring women into urban planning.

Pratima Joshi believes that “women bring empathy and sensitivity” to the city-making process. “When I started, individual-level data was mostly on men. The datasets completely left out women and their experiences which created a Gender Data Gap. Girls and women are invisible to decision-makers because information about their lives is incomplete or missing. So, we made sure that women are adequately represented in data sets, especially on sanitation-related issues, and we co-created data with mostly women volunteers. The data is also disaggregated by gender. This ensures the interventions are women-friendly,” she says.

Paths ahead

Around the world, various ways have emerged in which women have made a difference to city-making. As Barcelona’s first woman mayor, Ada Colau, elected in 2015 and re-elected in 2019,[23] turned her advocacy for housing rights into improving housing conditions and participatory processes, among other things. She collaborated on the platform Decidim Barcelona,[24] where citizens can access information, suggest and debate ideas, and help the government evolve its agenda. The collaborative, public, and free ecosystem has encouraged people’s participation in city-making – including pf women.

Says Dr Kanchan Gandhi: “The politics of care gets interwoven into the city when women come on board. Women architects create more fluid and flexible urban spaces, they understand the need to strengthen public transport systems, mix land uses, and create inclusive public spaces.” Her work in Ludhiana, Jalandhar and Amritsar showed that the cities depended heavily on public transport but women were absent after sunset on streets. “Women’s marches, night walks or rides, safety audits can help to sensitise women to the broken infrastructure that prevents them from accessing public spaces. When women map these, they find them too ‘masculine’ and demand interventions to make them more accessible. In my neighbourhood, a park that women avoided after sunset became gender-inclusive after LED street lights were installed.”

Far away in Paris, mayor Anne Hidalgo’s fight to reduce air pollution and transform Paris into a greener, more sustainable city has been ongoing since 2014; she was re-elected in 2020. She pioneered the pedestrianisation of River Siene’s banks, much to car-owners’ dismay. Despite legal challenges, parts of the bank are reserved for walkers and cyclists, which has helped reduce pollution too. Additionally, she initiated measures to address congestion; the climate action helped reduce Paris’ carbon emissions by 40 percent in ten years.[25]

“Planning authorities need to listen to people, include and engage them in the decision-making process,” suggests Pratima Joshi. Adding to newer approaches to city-making, Dr Lalitha Kamath states the need for “leadership roles that are more focused on care and community” while also enhancing women’s mobility and safety to increase women in the workforce. “It’s not always about the best practice, it is also about how we can scale these practices sensitively,” she states.

Start at the beginning, says Anuradha Parmar. Include women “at the beginning when cities design urban policies where issues can be brought forth by marginalised groups themselves”.

Women planners and architects recommend a simple step forward: all practitioners should add the gender lens to all urban planning and design work. This approach to city-making would lead to incremental changes, small but significant, to make cities more inclusive. The burden of inclusive and gender-responsive city-making need not fall on women practitioners alone.

Shivani Dave is an architect, writer and illustrator interested in exploring the intersection of architecture and social sciences. After graduating in architecture from Mumbai, and in media from the London School of Journalism, she is applying the fundamentals of architectural research and writing within urban contexts to develop phenomenological ideas about life in cities. She researches, writes and illustrates in Question of Cities.

Illustrations: Shivani Dave