Places, they say, tell stories. When we look around our cities with children in tow, seeing the built environments from their perspective, what stories do our cities narrate to them? Do they tell children any stories at all or are our built environments so mundane and functional that children merely use them with no thought or curiosity? How poignant a loss it is to grow up in a city but not have connections to it or memories of it, to live with only a passing relationship.

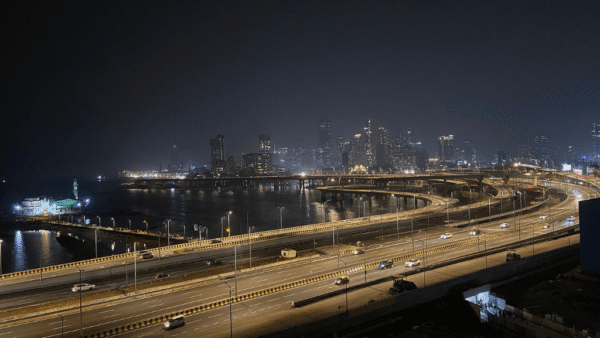

Cities and all forms of built environment in them – streets, pavements, buildings, parks, gardens, markets, open spaces and maidans – have purposes and functions that determine the quality of our life. They are discussed and pencilled into plans. We discuss housing, transport and mobility, schools, hospitals, workplaces and economic hubs. Relentless advocacy has resulted in some plans making a cursory nod to ecology and climate change.

However, all of this serves an average person, the able-bodied working man. It took decades for urban plans to adopt the lens of gender, of the underprivileged, if at all. Children’s turn has not yet come. This cannot continue. Children live in urban spaces and are shaped by them too. Research has shown that the built environment in cities – what it offers, what it lacks, what is accessible to children and what is not, what is public and safe – all determine their life, mobility, play, and a sense of belonging.[1] Yet, what we want cities to mean to them is rarely discussed or purposefully created.

A staggering 128.5 million children, equalling the population of Mexico, live in India’s cities; nearly 8 million of them below the age of 6 years live in poor conditions in informal settlements, according to the National Institute of Urban Affairs.[2] If we fail to plan and build sustainable and inclusive cities for children, we fail them all. Housing remains among the greatest of challenges in cities around the world for children with millions living in slums but it’s not the only one. Access to education, water and sanitation; air pollution, malnutrition, road safety, ecological and spatial inequalities, violence and the absence of child-friendly public spaces are other significant ones.

In the planning, designs and models of urban development, questions about what kind of childhood we owe children, across class and community, and how to make it possible should weigh on us all, especially so on policy makers and planners. The fact that they do not means children remain invisible and unseen in urban plans and designs.

It’s all in our imagination. Why, for example, can there not be a thoughtful public-access play space with daycare facilities in a business district for working parents? Or neighbourhood maidans and green spaces around local water bodies that connect children to the earth and nature? If we expect them to be sensitive to ecology and care about climate change when they are older, is it not our responsibility to provide them the spaces and opportunities to bond with the blue and green in cities?

Guidelines that should be mandates

UNICEF and UN Habitat jointly, in 1996, developed the concept of child-friendly cities. Two decades later, in 2017, the UN published a handbook titled Shaping urbanisation for children on child-responsive urban planning.[3] It works as a reference document for planners and policy makers to incorporate the relationship between children’s development and spatial planning into city plans.

The handbook also highlights the different needs that children have at different ages in their growth arc – and their varying needs for space. The needs, it points out, are across natural space, open space, and even hidden space. Cities, it recommends, should provide safe and inclusive public and green spaces at all ages that promote outdoor physical activity and offer opportunities for healthy development.

So, public playgrounds, recreational green spaces, public squares, pedestrian streets and pathways that connect neighbourhoods and communities – school to home and home to friends’ houses – should be in urban plans. But the guidelines and recommendations have not yet become mandates in cities. Children cannot collectivise and place their demands with authorities and policy makers, but surely adults in these seats can think about – and think for – children.

Green space was positively associated with children’s quality of life as did overall perception of the built environment and neighbourhood satisfaction in this review of studies; infrastructure did not show a direct correlation, though.[4] This implies that planners and policy makers must move beyond the physical infrastructure to create green precincts and neighbourhoods that support children’s development.

Child-friendly or child-responsive

Just as the UN moved from child-friendly to child-responsive in the two decades, a section of urbanists and the UN itself moved on further to child-participation and child mainstreaming (like gender mainstreaming) in urban plans. These are a mouthful of words but the nuances matter.

Child-friendly cities or spaces are meant to be suitable and appealing, comfortable and safe, for all children at all times. The UN set up the Child-Friendly Cities Initiative to take the idea further.[5] Child-responsive cities or spaces go a step further to prioritise or emphasise the different needs of children across age groups, and build or design accordingly. Of course, the attributes of suitability, comfort and safety prevail here too.

In 2023, its guidelines were released “to support governments at all levels to create urban spaces where children can access basic services, clean air and water; where children feel safe to play, learn and grow, which includes ensuring their voices are heard and their needs are integrated into public policies and decision-making processes”.[6] They highlight the critical role of policy and legislation as drivers of change, and set down minimum expectations for people in power in all aspects of children’s development.

Child-participation, a seemingly big word, takes the approach that cities and spaces should be planned and designed with the needs and desires of children as expressed by them. This, obviously, calls for a mechanism at school and/or community level to have children participate in a meaningful way. How, in the Indian context, can this include children from all communities and classes, and not get cornered by a few privileged, is a concern.

India’s cities are clearly far from child-participation but even if our urban plans were made more child-friendly, it would be a step ahead. It could ease the prevailing top-down control-led approach to planning and building cities – a reflection of the control that adults exercise on children anyway. Cities and spaces built in a child-responsive way or with child-participation also become inclusive and safe for everyone.

Play and play spaces

The value of play and recreation is ignored or undervalued but they determine our quality of life. More so, for children. Play and recreation can, indeed, mould people and make societies. Whether it was Aristotle who remarked that Sparta never flourished in times of peace because its constitution “has not trained them (Spartans) to be able to live in idleness…” or the 20th century philosopher Harry Overstreet who wrote that “recreation is a primary concern, for the kind of recreation a people make for themselves determines the kind of people they become and the kind of societies they build,” play was treasured. In modern cities and urban lifestyles, it has been stolen and, especially so, from children.

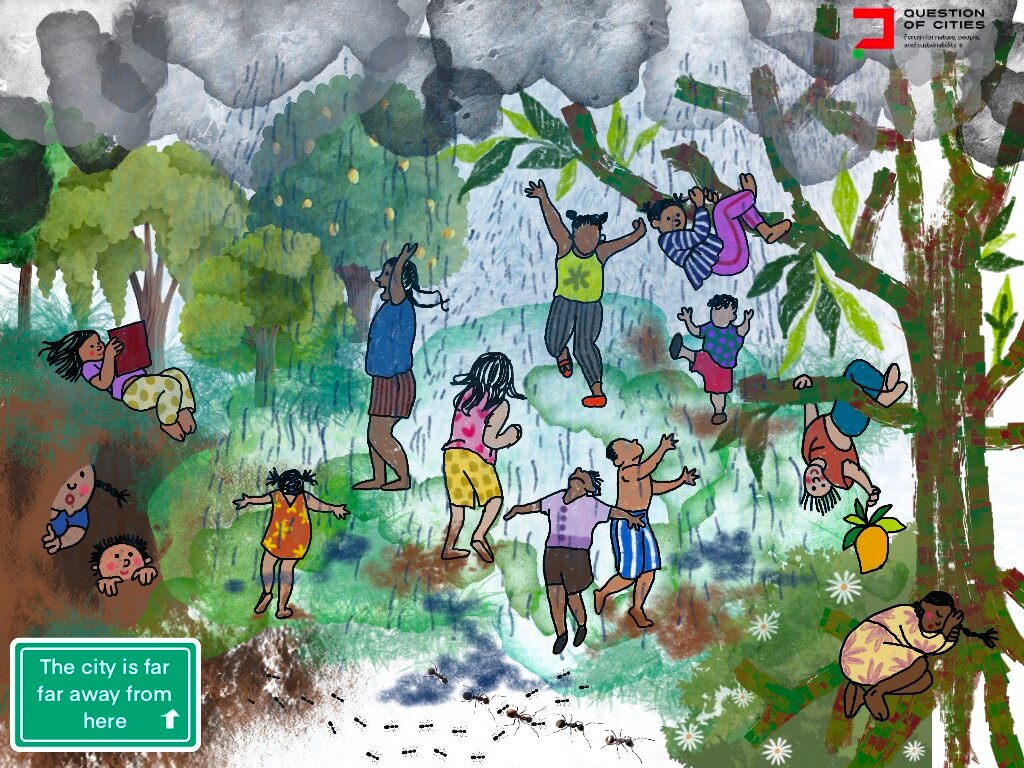

Play is a natural way for children to keep busy, stay active and find joy but it’s more than that, as studies have shown. Play – free play, unstructured play, even structured play – with peers and others, is essential for babies and children of all ages not only for physical development but also for cognitive, social, and mental development. They acquire skills that cannot be learned elsewhere, they learn about themselves and the world, they discover relationships and build networks.[7]

If the value of play has been proved, not that it needed to be, why do cities not have more play spaces? Why do some children, whose parents can afford private and luxury spaces, get to play while a vast number make do in crevices and corridors of buildings? Urban planning, at best, reserves space for parks and gardens – at least in well-off neighbourhoods – but open spaces, maidans, and tree-filled orchards are few and far between. Play is also when children climb trees, pedal away on pathways, create impromptu games in the open, find a water body to float paper boats, watch a stone sink into the water and a feather float on it.

Planned playability has not received the attention it deserves. Gated complexes in cities have play spaces but that’s hardly enough. Thoughtfully-designed and safe public play spaces are rare, forcing parents who can afford private activities to subscribe to them. Some play may be better than none but sequestered spaces – play pens in brightly-lit and exclusive spaces where children from similar socio-economic profiles dance or skate – are hardly what the philosophers meant by “learning to idle”. The absence has also meant children have come to rely on digital devices and social media – hardly healthy.

The fundamental question: why is playability, access to play spaces that encourage open and unstructured play, not a part of the core city-planning like water supply or pavements are?

Cities that show the way forward

All of this seems utopian but, as people working in the domain assure, it is not so. But let’s not take anybody’s word on this. Let’s look at cities that have consciously become more child-friendly or child-responsive, a few have even enlisted children’s participation. The way forward lies in the examples these cities have set.

Sharjah is a surprise. In 2017, even as the UN rolled out its guidelines, the Emirate brought out its ‘Planning Principles Guidance for Child-Friendly Open Public Spaces’, designed to influence its infrastructure and evolve an action plan for a child-friendly city.[8]

For ‘PlayStreets’ or ‘learning through play’ in Philadelphia, it was necessary to have champions on the ground and establish the Office of Children and Families, in 2020. Bringing the concerned city departments under one umbrella to ensure that policies and services for children and families are coordinated with the school district there was important.[9]

Tim Gill, an independent scholar, writer on childhood, a global advocate for children’s play and mobility, and author of Urban Playground: How child-friendly urban planning and design can save cities[10] advises three pathways to creating child-responsive cities – a strategic focus cutting across departments as in Rotterdam which reimagined itself as a child-friendly city between 2006 and 2018, a single department approach focused on transport or parks as in Vancouver and Antwerp, and partnerships with civil society organisations.[11]

A comprehensive volume on the subject is by Natalia Krysiak, a Sydney-based architect who set up ‘Cities for Play’ and travelled across Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, United Kingdom, Belgium, Netherlands, and Canada to document case studies from cities.[12] In her analysis, she suggests design interventions (care-free neighbourhoods, playable streets, community toy box, nature play, parent salon), programmed interventions (neighbourhood play web, hacking the playground, designing cities with children), and policy changes at municipal level to build inclusive cities for children.

By 2030, an estimated 60 percent of urban residents in the world will be below 18 years old and, of these, nine of every ten will be in Asia and Africa.[13] In sheer numbers, India has a strong reason to pay attention to children and space in cities. How we build our cities matters – to children and our future.