Pune rests at the confluence of two rivers, the Mula and the Mutha. The old city centre has the Mutha flowing along it while the Mula is the natural boundary between the city and its industrial twin, Pimpri-Chinchwad. Then, the two meet to be called the Mula-Mutha, which flows east through Pune and meets Bhima River downstream. The relatively clean water and lush riverbanks gave way, over the past few decades, to untreated sewage in the waters, solid waste dumped on river banks, construction encroaching on floodplains, and channelisation of the river courses. This assault on the ecosystems of the rivers has been compounded by the river ‘beautification’ or Riverfront Development Project (RFD).

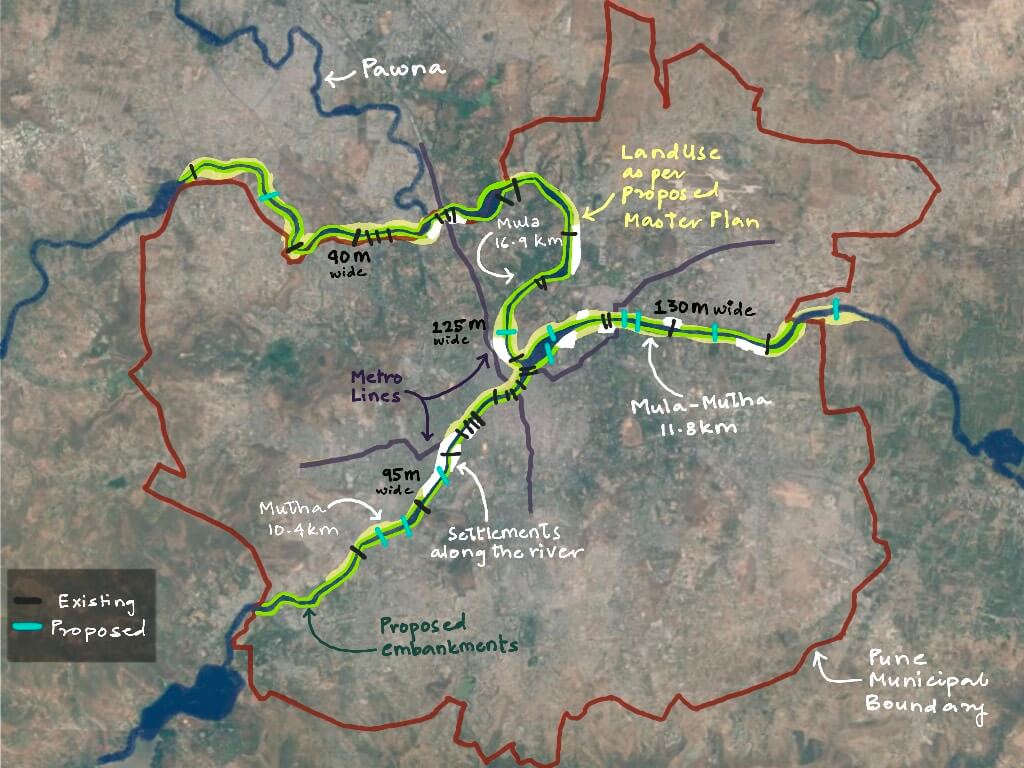

The highly controversial Rs 5,500-crore Riverfront Development Project, conceptualised in 2015-16,[1] planned to “rejuvenate” the Mula, Mutha and Mula-Mutha across 44 kilometres by constructing embankments, walkways, plazas, access roads, gardens and planting trees along the river banks. The construction also includes two barrages to impound water to probably make the rivers look ‘full’ like the riverfronts of the Sabarmati in Ahmedabad. The focus is not on restoring the rivers to their ecological health, but on creating infrastructure to unlock real estate value on the riverfront. This is development by another name – at the cost of ignoring science, increasing the risk of flooding, and downplaying ecological destruction.

The RFD project, aiming to construct a 22.5 lakh square metres built-up area, has got less national attention than it should have. But in the restoration and health of the rivers – not more construction and channeling – lies the ecological security of Pune. This is important as the city finds itself battered by unusually heavy rainfall, as in this July and August, leading to large-scale flooding and waterlogging. Old-time Punekars have stories of languidly swimming or boating in the rivers, of how the waters rose and occupied the floodplains when it rained heavily; they lament that the rivers are not the same.

The RFD project worsens the gradual diminishing of the hills and forests around the city to accommodate its expansion. It is an assault on the rivers’ ecosystems like no other – a gleaming symbol of post-liberalised ‘infrastructure development’.

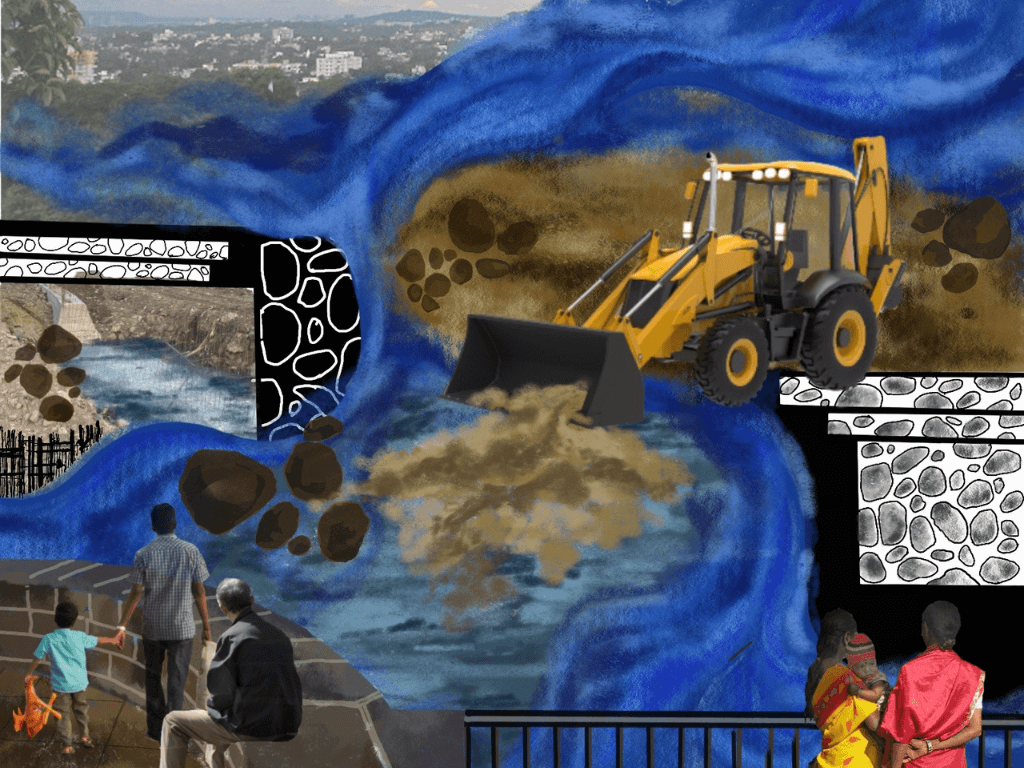

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf

Intertwined with the city

The Mula, Mutha, and Mula-Mutha are deeply intertwined with the ebb and flow of life in Pune, especially its water needs and rainwater drainage. With four dams – Khadakwasla, Panshet, Varasgaon and Temghar – on the Mutha, it provides for much of Pune’s water requirements. The Mula is also dammed at Mulshi where Tata Power plant is situated. The Pawana, a tributary of the Mula, flows through Pimpri-Chinchwad and supplies water to the city through a dam.

All the dams are in the Western Ghats, a global biodiversity hotspot and a notified Ecologically Sensitive Area, a UNESCO-certified world heritage site for its phenomenal biodiversity, which is a high rainfall region subject to cloudbursts and consequent heavy flows from the dams. In 1961, a cloudburst led to the breach of Panshet dam, causing heavy devastation and massive loss of life in Pune. This was when climate change was not as fierce. Ignoring scientific advice about filling the dam has apparently led to the devastation then. Is Pune about to make a similar mistake with the RFD?

The rejuvenation of a river should include controlling pollution in it, and protecting and restoring its natural ecology. However, these aspects are largely missing from the RFD proposal. There is no evidence that the massive budget includes sewage treatment. As much as 80 percent of it, according to the project plan, has been earmarked for the construction of 22.5 lakh square metres built-up area and 20 percent for landscaping and related work. The Pune Municipal Corporation contracted HCP Design, led by architect Bimal Patel, to undertake the project;[2] the firm’s similar project on Sabarmati River in Ahmedabad has drawn some flak.

It has been inspired by riverfronts in cities of Europe and the United States built decades ago but these were revenue generation models, explains Shailaja Deshpande, founder-director of Jeevitnadi and a pillar of Pune River Revival movement that is fighting for scientific and eco-sensitive rejuvenation of rivers. Many European riverfronts were planned after World War II to raise funds through real estate development; while these may look attractive from a distance, they are plagued with problems, adds Jaideep Baphna, actively involved with the movement. When Indian rivers have a different ecology, seasonal variations in water flow, and different climatic conditions, why should Indian cities copy-paste such models, ask Pune’s environmentalists.

Illustration: Nikeita Saraf

Less flooding or more flooding?

One of the stated objectives of the RFD project is to clean the rivers and make them free of pollution. However, allocation has not been made for sewage treatment. In any case, cleaning need not be tied with the construction because the PMC had received a grant from Japan International Cooperation Agency more than five years ago to build 11 Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) and upgrade nine existing ones. Only after the citizens’ movement did the PMC start work on these plants, says Deshpande. Even after the completion of this work, almost 400 million litres a day untreated sewage is likely to enter the rivers, not accounting for population rise. So, the problem of solid waste remains.

Another stated objective of the project is to reduce flooding. For this, the encroachments on the floodplains will have to be removed, the riverbed will have to be freed of obstacles, construction permissions in the flood-lines will have to be revoked, solid waste dumping in the river prevented, natural drainage of the banks retained so rain-water flows without obstruction, and natural vegetation along the banks retained to stabilise them, prevent soil erosion, and check water velocity. Does the RFD project do any of this? No.

The Detailed Project Report shows that the width of the river channels will be reduced; in some areas, to just 90 metres from the current 150 metres which will lead to a rise in the water levels around. However, this increase only considers the water released from dams and not major streams like Ambil Odha, Bhairobad Nala, Ramnadi and Nagzari Nala which carry considerable water in the monsoon. A cloudburst in the catchment of the Ambil Odha in 2019 caused unprecedented floods in Pune.

A report by The Energy Research Institute[3] shows climate change-induced increase in Pune’s rainfall and more cloudbursts. The report states that climate change would increase rainfall in Pune by 10 to 32.5 percent by 2030 and a likely decrease in the number of rain days which could mean more cloudbursts. Many areas of Pune face waterlogging in the monsoon due to insufficient stormwater drainage and bypassing natural drainage patterns while constructing buildings and roads. Constructing tall embankments will further cause pluvial flooding. In the recent rains, the under-construction embankments themselves were submerged in many places.

The RFD, in all fairness, has not adequately considered flooding risks. The flood calculations in its Detailed Project Report are inaccurate, underestimate flooding, and ignore the projected increase due to climate change.

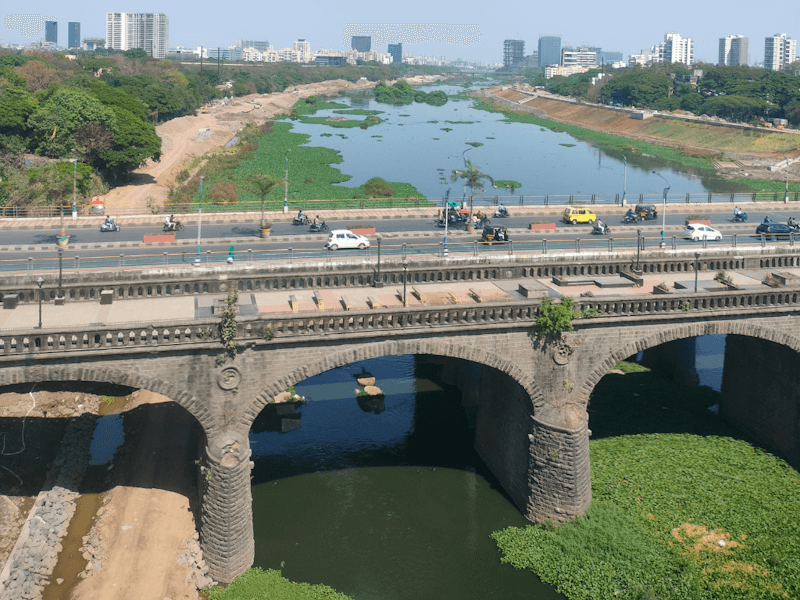

Photo: Kedar Champhekar

The problematic embankments

River embankments, according to the Indian Standard Guidelines for Planning and Design, should be constructed on natural ridge of riverbanks. However, in the RFD, they are on the riverbed. The PMC proposed new flood-lines[4] have been shifted towards the middle of the rivers, possibly to permit construction. The PMC claims[5] that the cross-section of the river will be increased, however the Detailed Project Report shows[6] that the cross-section will significantly reduce. Activists have pointed out several glaring errors in the drawings – for example, the water level at the Mula-Mutha confluence is shown higher than the level upstream.

Another factor that could exacerbate flooding is the PMC’s revised flood-lines. In 2016, the municipal corporation revised the flood-lines, reducing the extent of the floodplains and began permitting construction on the floodplains. The irrigation department rejected these flood-lines as invalid, yet the PMC did not budge. If flood-lines had to be revised, they should have included more of the river banks; instead, they are pushed further into the rivers.

Architect and activist Sarang Yadwadkar explains that a PIL had to be filed in the High Court which, on June 26 this year, ordered that the flood-lines must follow scientific procedures. The PMC will have to correct the flood-lines and remove all construction it permitted on the floodplains.

Nature’s bounty of flora-fauna

Even though Pune’s rivers are polluted and encroached upon, they demonstrate the incredible resilience of nature in their great diversity of flora and fauna. There are 316 species of flora and 77 species of birds found in and around the rivers, according to Jeevitnadi’s survey. Birdwatchers recorded 208 species in the RFD area on the open-source platform, ebird.

Photo: Kedar Champhekar

More than 150 species have been documented only in the Salim Ali Biodiversity Park, a stretch of the Mula-Mutha river bank from Bund Garden Bridge to Kalyani Nagar Bridge, named after the famous ornithologist and initiated by the late Dr. Prakash Gole, Pune’s eminent ecologist and ornithologist. A prominent Pune family had donated land for the sanctuary but it was never notified. The area suffers from large-scale solid waste dumping; a local builder has claimed a part of the land threatening activists who fight for the sanctuary.

The river here retains its natural rocky banks and has habitats for many migratory waterbirds. However, this is one of the first stretches of the riverfront that the PMC started developing. The ecology and biodiversity survey conducted as a part of the mandatory Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) was done so poorly that it recorded only 46 species of flora and 12 species of birds. The scientific errors speak for themselves; secondary data has not been quoted which is mandatory for EIA.

The Mula-Mutha riverbanks from the Sangam to Kalyani Nagar is lush green with thousands of trees. The Detailed Project Report says that no trees will be cut; the EIA also affirms that trees will not be cut. However, after the project was cleared, the PMC applied to the Tree Authority for permission to cut a staggering 6,062 trees.[7] Activists pointed out that the trees were marked without regard to species or age.

Photo: Kedar Champhekar

Contradictions galore but people fight back

There are glaring contradictions between the Detailed Project Report and the Environment Impact Assessment report on various aspects. The riverbed will be deepened by 2 metres which will destroy the habitat for fish and many invertebrates, and irreversibly alter the aquatic ecology, but the EIA has no studies on this. In fact, the EIA contradicts the Detailed Project Report on this and other aspects – the EIA says the riverbed will not be deepened but the project report states 2 metres increase in its depth; the EIA says there is no built-up area but the project report shows 22.5 lakh square metres – 556 acres – will be created; the EIA mentions no existing structures to be demolished or conserved but the project report lists several temples, samadhis, ghats, low bridges, even slum pockets that will have to go.

“We have all the necessary clearances and they are out in the public domain. We have also got environmental clearance from the State Environment Impact Assessment Authority,” said PMC’s environmental officer in 2022.[8] However, it did not convince people back then, nor now. They train guns on the PMC because the civic body is answerable to citizens. This is deliberate destruction of the rivers and it’s criminal, says Mukund Mavalankar, a senior citizen and part of the Pune River Revival movement. He started a unique fasting campaign to raise awareness; many youngsters from Fridays for Future joined him in chain fasts. This started on February 27, 2022, and volunteers have been chain-fasting since with more than 250 people participating. Enthusiasts have fasted multiple times; Narendra Khot has done 85 times.

Photo: Hardik jadeja/Wikimedia Commons

The Pune River Revival Movement has brought together citizens from different fields who have been organising rallies, protests, awareness walks, online talks, social media campaigns, research, and taking legal recourse. It is heartening that well-to-do citizens, who generally stay away from social movements, have joined in large numbers. A signature campaign at Bund Garden displayed bottles of polluted water from the rivers which spurred people to join, a Chipko Andolan was launched against the proposed tree-cutting, awareness walks, rallies and social media buzz are all being used. Beyond these, a difficult legal battle is also being fought. “This movement is totally apolitical and supported by citizens,” says Shailaja Deshpande. In November last,[9] the National Green Tribunal deferred the environmental clearance and ordered a revised EIA before work could proceed.

Who is the RFD project for? Its stated objective is to create a continuous public realm along the rivers. Creating new land and opening it up for ‘development’ would benefit real estate developers and politicians vested in them. In fact, the PMC itself intends to raise funds this way; when a sample stretch of the riverfront was done, the PMC first invited builders. Like the Sabarmati Riverfront[10] in Ahmedabad, this riverfront is also imagined just as a recreational space for the middle classes.

However, the rivers belong to many – people who graze cattle on the floodplains, washermen, fisherfolk, the poor whose slums are on riverbanks, street food vendors who use spaces under river bridges, cyclists and two-wheeler drivers who use the road on the edge of the riverbanks, birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, small animals and birds who nest and find food along the river. Without elected representatives in the PMC – elections were due two years ago – people’s voices are not heard there.

Yet, they persist in the fightback. The Ecological Society, a civil society organisation, even prepared an alternative plan which will cost less than 50 percent of the RFD budget and rejuvenate rivers ecologically. Citizens want clean rivers that flow naturally, support biodiversity, and have the capacity to handle floods besides preserving heritage on the riverbanks. Recreational avenues, they say, must integrate the natural beauty and ecology instead of shiny, lifeless concrete that the RFD set out to do. But neither the PMC nor the project developer are interested.

This essay was enabled with inputs from the Pune River Revival: https://puneriverrevival.com/ and Jeevitnadi: https://www.jeevitnadi.org/

Kedar Champhekar is a Pune-based freelance ecology expert, who carries out ecology and biodiversity surveys for environmental impact assessment (EIA) and other purposes. He has 17 years of experience in biodiversity education, outreach and assessment. He teaches in various colleges and is involved in biodiversity education and awareness activities.

Cover Photo Illustration : Nikeita Saraf