And quietly flows the Hooghly. Along Kolkata’s western edges, cutting a wide swathe across the plains of Bengal, as a tributary of the Ganga, the Hooghly flows approximately 260 kilometres. It was on the banks of the Hooghly that Job Charnock, an employee of the East India Company, was said to have founded the company’s headquarters in a swamp called Sutanuti.[1] Three villages – Sutanuti, Gobindapur and Kolikata – formed what came to be known as Calcutta, the erstwhile capital of the Company. The river brought the British to Calcutta. Much water has flown in the Hooghly since. Calcutta is now Kolkata.

The Hooghly passes through districts in southern West Bengal before flowing past the twin cities, Kolkata and Howrah, towards the Bay of Bengal. It was an important transport channel and colonial trading port in the early history of Bengal. The Dutch and French colonies at Chandannagar, on the Hooghly, rivalled those of the British but were eclipsed in the colonial wars. The Hooghly’s banks hosted several battles, including the Battle of Plassey or Palashi, and earlier wars against Maratha raiders. The river has been witness to political upheaval, the first war of Independence, Partition, refugees, the rise of the Left and more.

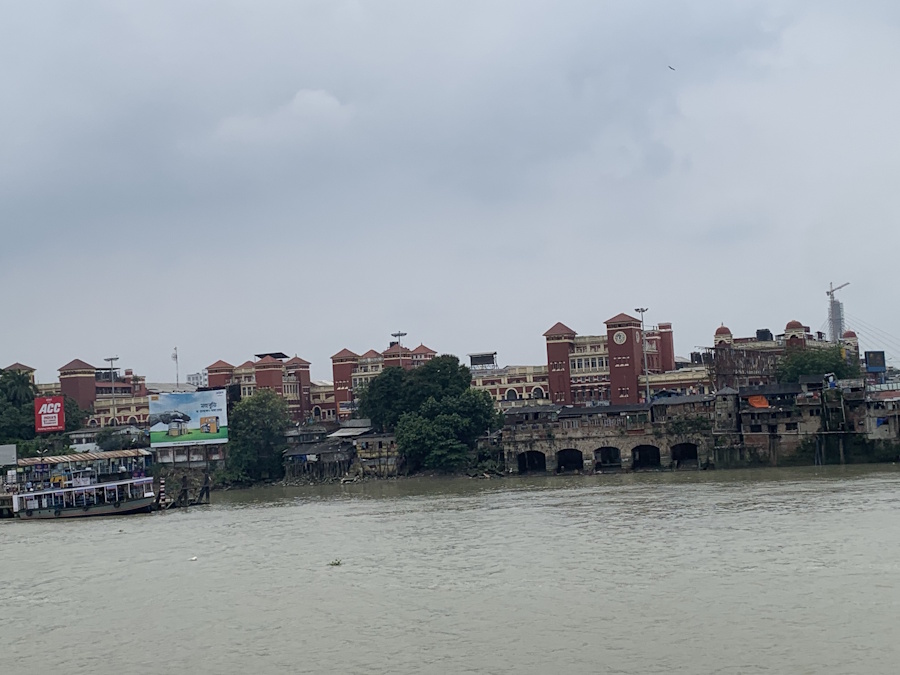

Immortalised in cinema and songs, the iconic river hardly has a happy relationship with the city now. It’s open and visible for barely 1.5 kilometres in the city. For a good part, its banks are dominated by garbage, debris, faecal matter higher than the permissible levels, crumbling structures including warehouses of the British era, derelict factories and ghats. The Hooghly appears to hide in shame though it should have been Kolkata’s asset and pride.

This was best captured by India’s legendary architect Charles Correa who had remarked, while in the city, that: “For an eternity, Kolkata has turned its back on its river, unlike Paris or London, and paid a heavy price for the apathy…Where else in the world would you have a sacred river flowing by with majestic buildings in the backdrop, yet, there is no connect between the city and the river? The city should be a celebration of the Hooghly.”[2]

Correa’s scathing criticism of Kolkata’s planners and administrations for neglecting the river’s relationship with the city went unheeded. Decades later, it is much worse as the expanding city puts pressure on its banks and new development, including luxury houses, are slated on its floodplains.

Photo: Shobha Surin

The sacred and the happy

The Hooghly was not always like this. I went a month back with a friend to immerse her mother’s ashes. When asked where she wanted to go for the immersion, she simply said, “at a clean ghat, please.” I recalled the same predicament I was in to immerse my father’s ashes.

All we want is a clean ghat to access the holy river to flow the ashes of our beloved ones. It’s hard to find. We both chose Babughat, the most popular steps where all kinds of religious activities are performed throughout the day.

The Hooghly also holds happy memories for my family. We would set out for our annual holidays crossing the Howrah Bridge, renamed Rabindra Setu, to reach Howrah station to board a long-distance train. The span of the blue-grey sheet of water always caught my attention. It’s a memory. Often, we would stroll on Sundays at Outram Ghat and sample street food bhelpuri, masala muri, puchka and more.

Later, as young adults, it was pizzas and ice creams from a snazzy joint here. The outlet has been shut for many years. Mostly, the Hooghly has largely been out of bounds for us living in Kolkata. The city sees a largely unkempt riverbank with filth, derelict structures, and neglect written all over.

The Hooghly-Thames connection

From Coin Street to Calcutta: A Tale of Two Pizza Restaurants by the British ship engineer George Nicholson narrates the riverfront development in London and Calcutta. Both had pizza restaurants but the similarity ends there. The thriving one in London, at Gabriel’s Wharf on the South Bank, speaks volumes about the public use of the riverfront; the one in Calcutta, at the Man-O-War jetty, stands forlorn and symptomatic of the difference in the city-river relationship.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Nicholson, who chaired the London Rivers Association (LRA) from 1987 to 2007, identified policy and responsibility gaps: “Town planning was focussed on land use, there was no policy on water space. The planning system was effectively blind to river development.” The LRA was created by the Greater London Council and local authorities to frame policies for water management. “It took 40 years to develop the riverfront,” Nicholson told this writer in 2017. The promenades on the South and North Banks of the Thames have people walking, jogging and strolling at the waterfront, the sandy bank with pebbles has artists creating artwork and children building sand castles.

Nicholson had been to the Hooghly riverside, at the invitation of the Left Front government, to suggest riverfront development. “It was totally derelict and walled in when I first saw it in 1987. The only public space was the Man-O-War jetty. The dock wall closed the river to the public,” Nicholson recalled, “The Calcutta plan had an elevated flyover over the waterfront, which was absurd and I told them so. We suggested a park on the waterfront. The millennium was approaching and they wanted a beautification project. So, the park was created.”[3]

The Millennium Park has since had two extensions—one to the south till Floatel and another from Fairlie Place to Howrah Bridge. Nicholson had recommended extending it to the Mullickghat flower market and restoring the warehouses along the river. The example was the defunct Bankside Power Station in London housing the Tate Modern as adaptive reuse of riverside space. Ironically, Nicholson drew inspiration from Calcutta to reimagine the Thames. “Till the 1970s, buildings had their back to the waterfront; when you walked along London Bridge, all you saw were backyards. We campaigned to build a pro-river attitude. It took 10 years but prime properties since are river-facing,” he said.

River-facing development

The last few years have seen real estate projects mark their presence on the west bank of the Hooghly. A grand project by a leading realtor is taking shape on the stretch from Rabindra Setu to Howrah Station. The 200-year-old salt golas have been demolished for luxury apartments spread over 17.4 acres. The developers have plans for ghats and promenades on the riverfront within their project area but these will not have public access.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Such development may not proliferate as large parts of the riverfront are, thankfully, owned by the Indian Railways, the Kolkata Port Trust, and the state government but there are no guarantees. The Hooghly is still navigable and sees a huge traffic flow.[4] For many decades, the Calcutta Port, now renamed Syama Prasad Mookerjee Port, was the biggest port of India but its significance reduced as a stretch of the river cannot be navigated due to silt.

The ghats or the steps

At the riverbank, traditional religious activities abound. The banks are dotted with 100-odd ghats or stone steps built in the early 19th century by zamindars, traders, or men of means for common people to bathe, wash, and pray. Crematoriums are situated on either bank of the Hooghly.

These ghats display marvellous heritage architecture, particularly those south of the Rabindra Setu. There are tiny ones and majestic ones spanning several yards—Sovabazar and Ahiritola ghats—reminiscent of the Varanasi waterfront. Calcutta is at its most ugly and most picturesque along the riverside that stretches for more than 20 kilometres, writes Soumitra Das, heritage correspondent of The Telegraph.

The sweep of the ghats is marred by development such as the Millennium Park. It’s a piecemeal development on the riverfront across only 1.5 kilometres. Its promenade, with elevated bridges and pathways linking Judges Ghat and Babughat, offers a view of the river vista. Pathways lined with palm trees, granite benches, and balustrades are, sadly, visible only through railings and gaps in walls.

To the north of Babughat are the Port Trust’s warehouses. Though architecturally significant for their red bricks with turreted and pedimented roofs, the 19th century structures that combined utility with raw beauty, are derelict. Several old houses are still seen on the Strand Road with the pedimented windows and doorways, pillars, porticos, and ornate cast iron grills.

Photo: Shobha Surin

People and the river

Two classes of people, the working class and street dwellers, use the Hooghly. Many cross the river to reach Kolkata in search of livelihood, using a ferry from Howrah railway station; thousands commute every day between the east and west banks of the Hooghly. Electric ferries now offer an environmentally-friendly option. The number is approximately 2,00,000 on weekdays and around half that on non-work days, according to the West Bengal Transport Corporation and the Hooghly Nadi Jalapath Paribahan Samanbay Samiti Limited which operate services. For street dwellers, the river is their living space. They use its water for bathing, cooking, washing clothes and daily ablutions. The rest of Kolkata merely passes by the river while driving on the iconic bridge.

Ferry users, street dwellers and others have not been a part of the state government’s efforts, however piecemeal, to revive the waterfront and the river’s ecology. Chief minister Mamata Banerjee, publicly professed her desire to “renovate and decorate” a stretch of the Hooghly like “London was created around the Thames”.[5] The one-year project was to have started in 2012. She envisaged a north-south pathway built on the east bank of the Hooghly.

However, it has innumerable and decades-old shacks and tiny shops besides the temporary shelters that the government puts up for squatters, especially mendicants and devotees, who come during the Ganga Sagar Mela, an annual pilgrimage at the confluence of the Hooghly and the Bay of Bengal.

The section to the north of the Howrah Bridge—dotted with derelict ghats, illegal warehouses and crematoriums—is essentially a vast open toilet zone, almost beyond redemption. The stretch south of the Bridge is where Kolkata’s relationship with the Hooghly can be renewed but there has been sheer lack of initiative. The procession of ghats and the abundance of greenery along the Hooghly, the city’s twin assets, seem wasted.

Several proposals from city architects and business organisations have been put forth. Most architects and city enthusiasts are of the opinion that some clean-up of the riverfront will help rejuvenate the area. Some have suggested a deep-dive heritage restoration along the river, including of the ghats and warehouses, while others recommend razing these and replacing them with mixed-use modern steel and glass buildings.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A landscaped promenade running north-south on the east bank appears in many suggestions. Economist and historian Sanjeev Sanyal, a member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council also made a presentation. “We can make (the river) a valuable asset from every perspective like heritage, conservation, urban landscape for working, living, and having fun,” he suggested.[6]

Despite the drawbacks, the Hooghly with Rabindra Setu (or Howrah Bridge) remains an inspiration for filmmakers and artists. French filmmaker Jean Renoir had used it not just as a backdrop but a powerful character in The River (1951). More recently, Hindi films like Yuva and Piku have used it in important sequences. Modernist painter Jamini Ray’s tempera depicts a sunset over the Hooghly. The late Bikash Bhattacharya’s Clippers on the Hooghly is an example of academic realism combined with creativity.

There’s a Bourne and Shepherd photograph of the Hooghly. Many colonial artists like William Hodges too have painted the river. Documentary filmmakers have depicted the river and its ghats as did film academic Madhuja Mukherjee whose video installation on Adi Ganga traces the route of the dying stream of water and mapping the city on its course.

The muse is there flowing, ideas abound. But the Hooghly continues to be filthy and disconnected from the city that draws so much of its identity from the river.

Anasuya Basu is an independent journalist and writer working on the intersections of urban development, conservation, climate change and migration. She has over 25 years of experience working in mainstream print media including The Telegraph of the ABP Group, Hindustan Times, Down to Earth. She is a Chevening Fellow and a state government-awarded reporter on child rights.

Cover photo: Shobha Surin