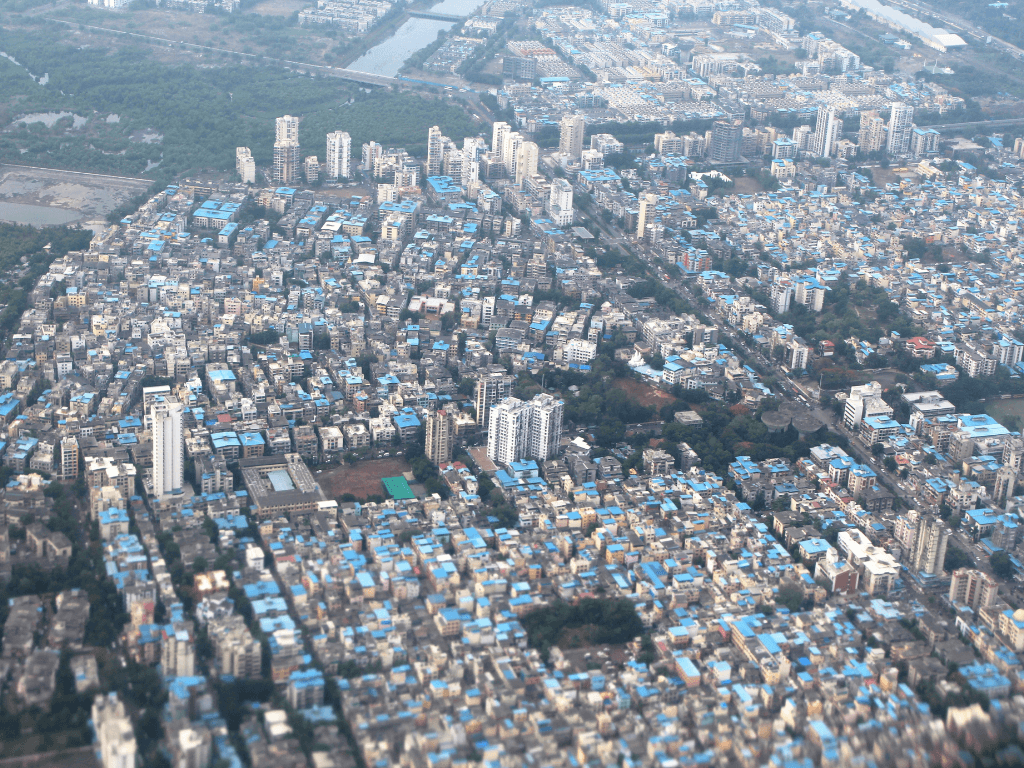

Phrases like ‘high density cities’ and ‘compact urban form’ have become oft-repeated mantras of those who occupy the power axis – governments, bureaucrats, corporates, and think tanks. Dense cities have been promoted as the model of urbanisation by multilateral institutions such as The World Bank[1] and unquestioningly embraced by countries and governments that confuse more construction – the build-more syndrome – with urban development.

The World Bank’s strategy documents recommended “urban transformation along these three dimensions – density, distance, and division” which translated into higher densities as cities grow, shorter distances as workers and businesses migrate closer to density, and fewer divisions as nations lower their economic borders. But this is not without costs – enormous costs – both to people and the environment. These, however, find little space in the enormous literature on the positive impact of density.

While not negating the benefits of density – higher productivity, shorter commuters, provision of public services, lower carbon footprint – research by the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), published in 2019, pointed to the less-discussed costs. Inequality ranked high among them as density made housing unaffordable for the large masses in cities, especially for low-skilled workers and first-time buyers. High density in cities, with people living and working in close proximity, has been shown “to lead to higher levels of inequality” besides “traffic congestion, exposing residents to higher levels of pollution and, partially as a result, higher mortality rates.”[2]

Inequality in cities, as an outcome of density, is a critical aspect requiring further attention; there are others. When high density is pursued as an economic goal, it becomes weaponised in the hands of governments with unquestioned profits for the power elite and a tool of discrimination of people and places in cities.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Moreover, dense cities that uncritically and unquestioningly follow the framework now face depletion of their natural ecology – tree cover reduced, forests shrunk or hacked, lakes built over, floodplains of rivers constructed upon, wetlands with new buildings – all of which can have disastrous implications in the times of climate change-related weather extremes. These aspects of density hardly get attention which this editorial expands upon.

Density weaponised for spatial order

When high density leads to “people just being warehoused into large buildings,” as the Congress for New Urbanism, the Washington-based non-profit organisation[3] called it, there are disquieting impacts. These must be closely examined especially in India where the ruling dispensation believes in the high-density ideology. “The country needs high-density cities which creates conditions for income gains by way of monetising land and generating tax revenues while having lower running and operational costs by way of laying cables, pipes etc…India needs to create dense cities which fits our aesthetics, our way of living and are economically viable,” said Sanjeev Sanyal, member of the Economic Advisory Council to the PM (EAC-PM) in December 2024 at the Global Economic Policy Forum, organised by the Union Ministry of Finance and the CII.[4]

In the hands of governments that have been more aligned with the interests of the corporate class and the uber wealthy, density has been gradually weaponised to achieve a number of ends: From enforcing control over the land and housing market, determining housing models that slowly squeeze the middle classes and the marginalised, making compact form an end in itself, disregarding basic human needs and requirements of families, perpetuating class divides in cities and forcing the brunt of it all on the poor and marginalised, and the commodification of land.

Photo: QoC File

Housing, besides open spaces, has been the most affected by the weaponisation of density. Housing, a social need and public service, is now viewed as a commodity and commonly referred to in the real-estate industry as “stock”. Its efficient production overrules consequences on people and environmental concerns. This build-more approach, focused on maximising production of high-profit and high-value housing, in which cities are turned into grounds for a rich harvest of real estate, is deliberately ignored by building low-grade housing, the non- or less-profitable housing options such as public housing and related services.

High density legislated as policies for private developers has meant they are pampered and empowered with the authority and control over critical public resources such as land. Density levels, when set down as policies, mean the monetisation of land and commercialisation of housing makes it deliberately unaffordable for most people in cities. Governments believe that their responsibility rests in making policies that allow high densities. The Slums Redevelopment Authority programme in Mumbai, emulated in the state and by other states, has pushed slumdwellers into a third of the plot forcing density to a staggering 1,500-1,800 tenements a hectare, against 400-500 tenements per hectare in the housing of the middle and upper classes. How can this varying class-based density policy be good?

There have been no evaluations at either macro or micro levels of how high density impacts the access to basic services and the quality of their lives. In SRA and low-income housing, high density has led to not only sub-standard living conditions for the majority but adverse impacts on their health, both physical and mental. Mumbai’s M-East municipal ward, which has among the highest density of population with nearly 70 percent of its residents in slums, had nine out of every 100, roughly 10 percent, of asthma-related deaths in the city, according to municipal data.[5] This year, researchers found that its heat vulnerability was also higher than other parts of the city.[6]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This, in turn, affects people’s quality of life and productivity – the metric that economists pursue. Super-high densities in the low-income areas of cities and tolerable densities in the better-off areas become a tool to enforce a questionable spatial order in the city. The built form, the facades, the character and feel of areas are, thus, influenced by density. Pushing untenable density under the guise of free housing has come to be seen as normal and accepted even by the affected. It is also furthered as a “successful model” seen in the jostling high-rises without adequate open spaces between them and the absence of amenities, as well as the number of people squeezed into densely-situated units, without adequate common spaces for people’s relief and interactions.

Density weaponised to silence

It is important to perceive and understand how the high-density built form has been used to first normalise and then silence the marginalised in cities. High density, promoted and sold as the panacea for all kinds of housing shortages, is often at its unliveable worst in the working class or poorer areas. This has now been normalised in our cities; it is somehow taken for granted that the marginalised sections – the lower-middle and poor classes – will have to make-do with much less space, in fact inadequate space, for their daily living. This is far from normal.

Often, the unique burdens that such living places upon people, families and communities, is romanticised and hailed as “the spirit of people” though it is merely their wretched day-to-day existence. In Mumbai and Delhi, also in other cities with slums, even toilets are a luxury and poorly-built community toilet blocks are known to give way endangering lives or push women to adopt routines that became unhealthy for them. The density in slums has been one of the excuses offered to not provide better or adequate sanitation. Worse, this subtle violence and exclusion have been normalised.

Photo: QoC File

The rent-seeking political economy in our cities, increasingly neoliberal and private-controlled, focuses on the distribution of essential goods and services as goodies, preferably prior to elections, which conceals or diverts attention from their right to these goods and services, and their deprivation. The profiteers benefit from such deprivation. Besides, these material benefits do not follow the minimum standards that are prescribed for the privileged sections in the city. For governments, the distribution of some spoils of privatisation and the accumulation of wealth by a few from the city’s common property resources, becomes their “urbanisation success” from which to draw political mileage.

Over time, this normalisation leads to the silencing of people because they are pointed to a laundry list of goods and services, especially housing, that they have been given “free”. Their demand for better amenities is politicised or postponed. And should they express dissent about the state of affairs, it is occasionally and selectively allowed – or ignored. Debate, dissent, social unrest which are natural political expressions of communities are silenced.

This is achieved because collectiveness and cohesion among people are often affected by high density in which close proximity and lack of privacy are further exacerbated by the lack of adequate light and air in the tightly-packed buildings, the absence of open spaces for community gatherings and socio-cultural events or people’s restricted access to them, and the resultant frustration or aggression. High-density play experiences get even less attention but greatly affect children. “Collaborative research between urban planners, architects, sociologists, child development experts, and children themselves could help to transform our understanding around play spaces in high-density areas, to better cater to children’s needs,” found this review of studies on the impact of high-density environments on children’s play.[7]

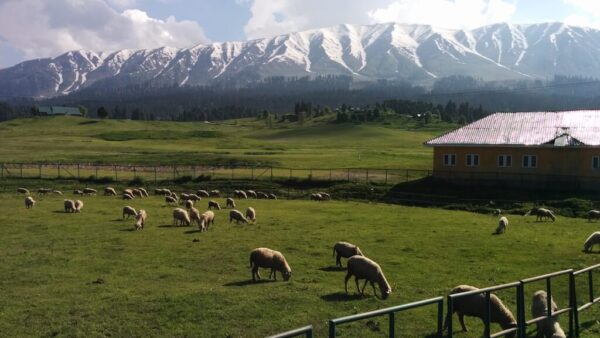

Density has an ecological cost

As the race to produce high-density real-estate commodities intensifies, the natural ecology in cities is at stake. Already, our cities have lost large tracts of their forests and hills, their water bodies and natural drainage channels,[8] and their stunning diversity of flora and fauna including some rare creatures. These natural elements and the complex webs of life that they support are inter-related and inter-dependent. When thousands of urban trees are hacked away, authorities deprive cities of their de-carbonisation and heat-mitigation potential.

The disconnection between density and ecology in Mumbai reflects in policies and rules that now allow construction on a plot from end-to-end leaving no open space around, and basements that go five-six levels deep to make parking spaces. This rips apart the ecology of the earth and the multiple webs of life that exist underground. Consequently, entire neighborhoods – and the city – will have only jostling high-rises without trees or any green. How such densely-situated buildings allow fire-fighting and evacuation in case of accidents is another debate altogether.

High-density development has an impact on urban flooding too. A study published in Science Direct in 2023[9] stated: “The analysis revealed that high-density development had an adverse effect on urban flooding and that the runoff characteristics of high-density development were not limited to those of impervious surfaces.” High-density development is a factor that causes flash floods and stagnation of water as there is no open ground to help percolation and that considering this factor in future urban disaster prevention plans is as important as other variables, it added.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

As cities grapple with increased frequency and intensity of rains, floods, rising temperatures, sea-level rise and other climate change-driven weather extremes, serious attention must be paid to land use and the high-density model that has been so uncritically embraced. Even if it served a few people well earlier, the era of climate crisis demands that it is honestly and thoroughly reviewed, especially as intense urban flooding and Urban Heat Island effect become endemic. The climatic events also leave a trail of imprints on the health and well-being of people – exacerbating the other impacts of high densities.

The posture of governments and private developers is that such climatic events and their outcomes can be overcome by technological, or engineering might despite evidence to the contrary from across the world. If private and government forces desire to go beyond their lip service to sustainable development, then reviewing high densities across cities in the context of their natural ecology would be called for.

In any case, it is time that the accepted belief that ‘high-density cities are desirable’ is examined with a critical lens. And course corrections made sooner than later.

Cover Photo: Wikimedia Commons