The Musi River cuts across the city of Hyderabad into two – the historical old ramparts in the south and the newer gleaming city in the north. Both Hyderabads, so to say, have turned their backs on the river that sustained them for over a century, refusing to look at it beyond its function as a water source and a drain for their waste. The city developed from the Nizam’s pearl city to India’s IT city of the 1990s, the expansion continued into the 21st century with the last two decades turning Hyderabad into sought-after urban real estate. All along, the Musi carried the weight and waste of the transformations, quietly turning into a channel of filth.[1] Once the lifeline of the city and the pride of the princely rulers, it has been an outcast for some years – useful to the city but not central to its imagination. For most of its 55-kilometres course along Hyderabad, it is a stagnant smelly cesspool, a puddle at some places, and distressing dry patches at others. The devastating floods in Hyderabad, in 2023[2] and 2025 [3], turned the attention of the people and the Telangana government to the river.

This attention, unfortunately, may now prove to be further undoing of the river. Repeated floods and the filth were opportunities, perhaps nudges from nature, to reimagine what the Musi could be to Hyderabad. Or, go beyond to re-envision the city if its development were to be led by the river and the intricate old network of water bodies. Hyderabad could have made the river its central piece with its north and south sides wrapping themselves around it. Instead, the Telangana government rolled out the predictable and ecologically-discredited idea of riverfront development[4] of the Musi. This means more construction and concretisation along its banks rather than ecological renewal of the river..

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Congress-led Telangana government’s riverfront development project includes IT towers, retail and entertainment spaces, multiple bridges across the river, amusement parks and water sports facilities. Fifty metres on both banks of the river are to be buffer zones with no construction allowed. Pegged at Rs 58,000 crore two years ago, the cost has escalated to a staggering Rs1.5 lakh crore[5] for the same stretch. In the name of this river restoration, the axe[6] has fallen on easy targets – the settlements and slum-like colonies on its banks. These hold an estimated 15,000 households (activists claim higher numbers), or about 75,000 to a lakh people, who have lived there for years – many with legal documents or pattas.

N Chandrababu Naidu’s Telugu Desam Party government formed the Kirloskar Committee after the floods in 2020, which identified these settlements as the problem and recommended their removal, besides other measures. The evictions in late 2024[7] led to an uproar because resettlements plans were not clear. Homes in settlements like Shankar Nagar and Shivaji Bridge had simply been marked ‘RBX’ (riverbed extreme) for demolitions, people were given only verbal notices, rehabilitation sites were 15-20 kilometres away which robbed them of their livelihoods, and there was no clarity on why they had to be evicted when new gleaming construction was being planned not far away.

If the Musi led the city’s development and reclaimed its buffer zones and floodplains on which the poor had their homes, might it have shown more compassion? If the Musi were to renew itself, would it adopt the glitzy, construction-driven riverfront development model?

Familiar issues, timeworn solutions

The issues with the Musi are visible across rivers in cities across India – neglected waters, rivers turned into nallahs, encroached river banks, floodplain areas treated as developable land. This is a shame, perhaps more so in Hyderabad, where the river was respectfully kept at the centre of urbanisation in the Nizam era.

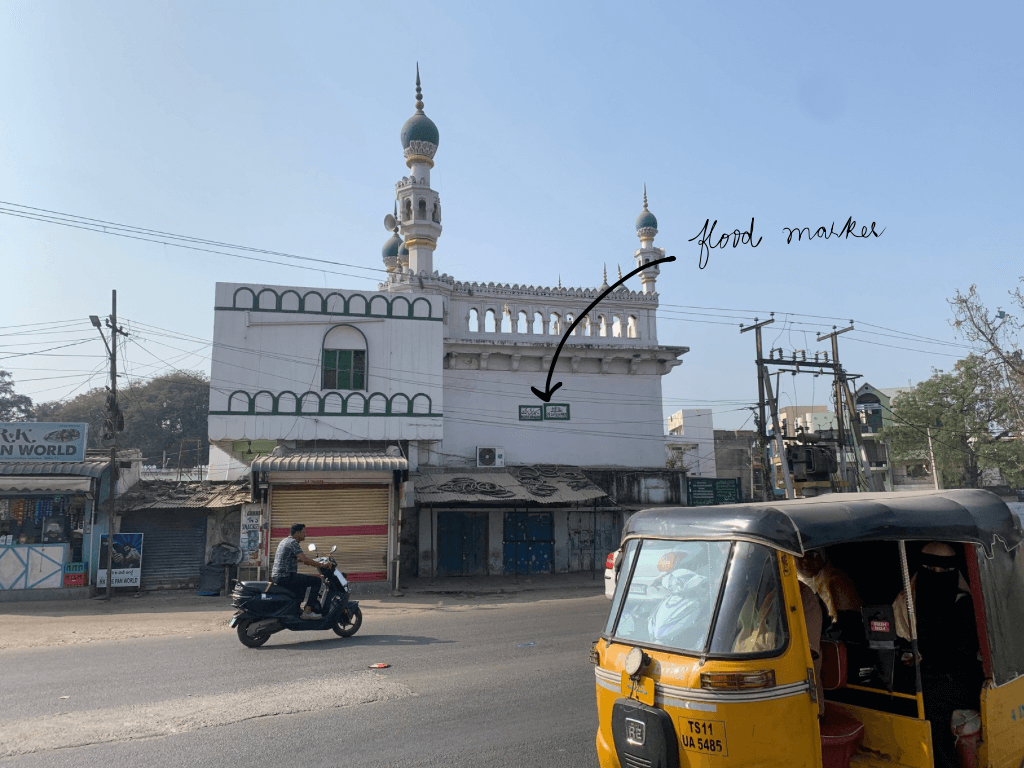

This was true especially after the devastating flood of September 1908,[8] which, in one strike is believed to have taken 15,000 lives, displaced thousands more, and led to several areas being under water for nearly 36 hours. The Nizam’s government, under the 6th Nizam Mahbub Ali Khan and his successor Osman Ali Khan, armed with the recommendations of India’s then foremost engineer Sir M. Visvesvaraya, began repair. Massive bunds were constructed from Puranapul to Chaderghat across the breadth of the city, major reservoirs were made to regulate the water flow – Osman Sagar was completed in 1920 and Himayat Sagar in 1927 – construction was banned in the floodplains, and the City Improvement Board was set up in 1912 to improve sanitation and water supply.[9] Besides these measures, public buildings were constructed on its banks as marvels of modern engineering. These buildings – the Osmania General Hospital, High Court, Telangana State Central Library and City College being some of them – stand to this day, braving floods and forming the backdrop of the vastly depleted river now. A planned corridor was also made with farms and gardens – 14 gardens – from the Osmania General Hospital to Chikkadpally along the gushing Musi, and plaques notified the public that the riverfront would be open from 4pm to 8pm. Marble slabs or tiles were placed on buildings along the river to display the level of the 1908 flood waters; only a handful of these have survived redevelopment.[10]

So, the Musi has seen planned and deliberate construction in the past too. What is different now is the scale and scope of the construction. The purpose now is to take over the river, impound its value as a natural asset in the interests of capital-led neoliberal city-making, and further disrupt the interconnections between the Musi and the city. The Nizam era built in relation to the river; the riverfront development is claiming the river and its spaces for the city while ignoring its urgent need of ecological restoration.

Photo: Shobha Surin

What river-led city-making could be

River-led development is not a new concept. The approach, essentially, moves from controlling natural water in a city and adopting engineering solutions for “keeping it out” to a development model and urban form that adapts to the natural water flow and cycles.[11]

This approach includes living with water (floating homes or houseboats in Seattle, Amsterdam and Rotterdam), making room for water by planning infrastructure and construction around its flow rather than ‘taming’ it, land zoning to maintain natural hydrological cycles, and integrating all aspects of the built environment with water spaces such as river banks, floodplains, and wetlands. For example, in Rotterdam which is below sea level, this approach has led to its streets turning into lakes, and bustling squares into water basins, during a heavy downpour. “This dual identity exemplifies water architecture, an urban living room by day, a flood basin by storm,” explains this essay.[12]

How would it be if Musi led urban development in Hyderabad? The principles would be similar: Placing the city’s hydrology at the centre of planning, hydrology-first principle in zoning, recognising and mapping natural drainage and water boundaries, planning for flexible and adaptive surfaces, building for temporality because water flows change season to season, integrating green areas into the plan as trees and forests act as water absorbers and groundwater rechargers, making waterfronts accessible to all people, and implementing neighbourhood-level micro projects (rain gardens, greywater reuse channels, bioswales). “In other words, let water dictate where roads, open space, and buildings go; not the other way around,” as this essay suggests.[13]

This is possible, say planners and water experts in Hyderabad. “The first change is to make the city co-exist with the principles and practices of natural designing. It calls for major reforms in urban designing and planning. All planning is now done for land, on land, without realising that land use changes will have repercussion on natural elements like water,” says Dr BV Subba Rao, former chief engineer in the irrigation department and geo-hydrologist, “Planning must understand the natural role or functions of the river, of water in any form, in an urban setting.”

Ignoring or bypassing this, deliberately or inadvertently while building, would spell disaster not just in Hyderabad but in any city as seen in the increased incidences of urban floods across India in the past five years.[14] Instead of maintaining or enhancing the river’s capacity to swell, its spaces have been reduced – by design. Popular government-backed projects such as the riverfront development bring more concrete to the floodplains and river edges that should be left alone. Dr Rao despairs, “in the name of restoration and beautification, we are doing all crazy things around rivers and lakes…Hyderabad has spent Rs 220 crore to revive the Hussain Sagar Lake but we have not integrated it into the city.”

A key point arises here – seeing rivers and water bodies in isolation. Water is hardly isolated; it flows and connects. Urban planning that constructs on or around water bodies, fracturing their network and isolating them, is a cause for localised flooding. If the Musi led Hyderabad’s development, it would demand the restoration of the entire water network that allowed its overflow to fill up tens of reservoirs and lakes.

This would lead to a fundamental change from the technocratic approach determined by real estate and financial interests to a river space that allows for a variety of functions for people without compromising on its quality, says an architect, requesting anonymity. The natural interconnection needs to be recognised and adopted. Activist Lubna Sarwath stresses on the ecology-and-people approach to city planning: “A river is a part of an ecology.”

The Musi would also get rid of or strictly regulate the polluting industries along its banks. Planners decry that there was never enough planning or implementation of rules for this. All this goes beyond having a Master Plan alone; it is about recognising the integrity of the river rather than seeing it as a receptacle for waste and untreated effluents. Even in its sorry state, the Musi has been serving Hyderabad by taking away its waste, acting as the city’s sink, points out a planner, “Shifting the industries is only a partial solution; the need of the hour is cleaner technology and treated effluents.”

Photo: Shobha Surin

The Musi might want to turn the clock back to the 1960s when it was primarily seen as a river flowing through the city, as Qamar Sultana and Asma Sultana write in their paper, A Review of the Deterioration of River Musi and its Consequences in Hyderabad City.[15] Disregarding the needs of the river to accommodate industrialisation and change in land use has meant the water turned unfit for human consumption and posed significant risks to public health and environment, this study Spatial and seasonal assessment of water quality of Musi River in India[16] pointed out last year.

Traditionally, tracts of land along the river were leased or gifted to locals to grow crops and fodder grass for horses and elephants; no construction was allowed. This changed over time as people migrated and industries were set up. Both led to the rampant landfilling of river spaces. In fact, law was flouted to build the Mahatma Gandhi Bus Station on the Musi river bed[17] Despite the Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs), the Musi water is highly contaminated, veteran environmentalist K Purushotham Reddy says, “The Musi is a river, it has to flow like a river.”

Sarwath echoes what many in Hyderabad desire: The Musi to be “aviral (unhindered) and nirmal (clean).” All said, the Musi is a seasonal river and would want to be recognised as such. This means respecting it enough to leave its dry floodplains alone when the water is a trickle. Planners point out that the river flows for about six months and remains partly or fully dry for the rest, but the expansion of Hyderabad, now extending beyond the river’s catchment area, does not take this into account. The very idea of the city, and how much of it can be serviced by the river, must be revisited. The Musi would want that.

Smruti Koppikar is a Mumbai-based award-winning journalist, urban chronicler, and media educator. She has more than three decades experience in newsrooms in writing and editing capacities, she focussed on urban issues in the last decade while documenting cities in transition with Mumbai as her focus. She was a member of the group which worked to include gender in Mumbai’s Development Plan 2034 and is the Founder Editor of Question of Cities.

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with more than 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she writes about climate change and is learning about sustainable development. She was most recently a Fellow of the Earth Journalism Network working on the issue of Non-Economic Loss and Damage suffered by communities due to climate change in Odisha.

Cover Photo: View of Musi River from Nayapul. Photo: Wikimedia Commons