In 2020, when the world was fighting the COVID-19 pandemic with strict lockdowns, the salubrious Goa saw another kind of a fight. Citizens, young and old, were busy saving the Mollem National Park, a part of the Western Ghats that have been internationally recognised for their biodiversity. The Amche Mollem (Our Mollem in Konkani) campaign was driven by volunteers who made art, managed the social media, coordinated with lawyers, and later organised protests.

“Initially, a small group of people came together in 2020 and realised the importance of protesting against these projects. Since then, it’s been completely citizen-led,” said a member of the campaign. “We were doing two main things — research-based activism and legal work. The Goa Foundation is looking after the legal aspect of filing cases.” It went to court against three proposed projects in Mollem — double-tracking the railway line from Tinaighat-Castlerock in Karnataka to Kulem in Goa, the Tamnar transmission line, and expanding National Highway 4A from Belagavi to Panaji. The activists campaigned to have the projects scrapped as they threatened to destroy the tropical forests of the Western Ghats and bring misery to Goa.

Looking back, they wonder if they made a dent because on September 10, the National Board for Wildlife cleared the 400KV Tamnar transmission line. When the construction starts, it would mean the beginning of the end of the Mollem National Park sprawled across 240 square kilometres. But they have a small win – the number of trees to be axed were brought down from one lakh to about 13,000. “We want no trees felled at all, the movement will go on,” says a member of Amche Mollem.

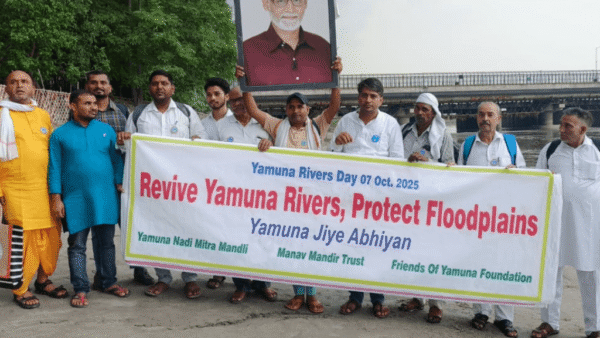

As in Mollem, so in cities and towns across India. Resistance movements and actions have been building up and clocking some wins on two aspects: Pushing back plans or proposed projects which put a heavy price tag on the environment and protesting for people’s rights in cities. After the pandemic, when nature began to revive itself because human interference was minimal, resistance movements have spread across cities – from Jaipur and Delhi to Guwahati and Kolkata, from Ladakh and Dehradun to Mumbai, Bengaluru and Hyderabad. Resisting governments and corporates to preserve nature and protect people is the leitmotif of our times.

Through direct action, use of social media, building alliances, employing legal recourse and more, people have taken it upon themselves to challenge governments or authorities who brazenly permitted environmentally-damaging projects. Or have banded together to assert their rights in urban spaces as Delhi’s slum dwellers did against the move to hide them during the G20 summit or farmers did to resist the three farm bills or doctors did to demand safer hospitals, to cite a few examples.

Photo: JosephAssisFernandes/Wikimedia Commons

Why resistance matters

Resistance became necessary as governments and authorities, mainly the central government, diluted key legislations like the Wild Life Protection Act 1972[1] and the Biological Diversity Act 2002[2] to allow development, passed orders to fast-track large residential projects in forest areas, and introduced a star rating system for states to speed up environmental clearances.[3] The Union Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change granted 12,496 clearances in 2022 compared to 577 in 2018; several policies, including the critical Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) notification of 2006, were diluted for private industry, stated a report by civil society organisations like PUCL and climate justice movements like Bahutva Karnataka in May.[4]

People’s resistance comes at a crucial juncture. India’s ranking on the worldwide Environmental Performance Index slid from 125 out of 180 countries in 2012 to the last place in 2022[5] while its position in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business rose to the 63rd position in 2019 from 142 in 2014.[6] Clearly, development is coming at the cost of the environment. As governments or authorities, custodians of the natural areas, abdicate their responsibilities, people have stood up to protect them.

Environmental justice activist and researcher Manshi Asher, also founder of Himdhara Collective, an environment research and action collective, says that cities are spaces with stark power hierarchies and “there are issues like gentrification, ghettoisation, caste, religion, and gender. The understanding that urban areas are modern conglomerations, and therefore these do not exist, is wrong. They are reproduced in a different form and sometimes get invisibilised in urban settings. Everything is more individualised, so there is all the more need for coming together.”

Even cherry-picking shows the wide span of resistance movements. The Aravalli Bachao group sought to protect Dol Ka Badh area, southeast of Jaipur, from being denuded of thousands of trees, 60 kinds of herbs, and 75 varieties of birds for a fin-tech park which, activists argued, could be located in an industrial zone.[7] In Delhi, people fought to preserve the greens and sacred groves of The Ridge.[8] Dehradun and Joshimath saw huge protests in defence of the fragile hill-station ecology.[9]

Mumbai’s Save Aarey movement may not have stopped the construction of the metro car shed but it foregrounded Aarey in popular imagination.[10] Activism to save Bengaluru’s lakes has been documented.[11] Pune’s Vetal Tekdi Bachav movement has gone all out to protect the hill. Activist Sonam Wangchuk, with hundreds of volunteers, went on a climate fast in Ladakh this March demanding legal protections for the region’s fragile ecosystem and life-giving glaciers.[12]

Many of these have a necessary local character but taken together they show, in the words of the celebrated American political scientist James C Scott, “…everyday forms of resistance (but) seen as a part of the vast realm of political actions”. He called this “infrapolitics” and noted that “everyday resistance is a dispersed, quiet, seemingly invisible and disguised form of resistance seemingly aiming at redistribution of control over property”. Scott’s work on “the dramaturgy of power” and the resistance to predatory states in everyday life[13] could, in the time of climate crisis, be extended to the environment. The everyday resistances take, other scholars have said, the form of temporary interventions to stop projects, acts of self-help, “guerilla urbanism”, and counter-hegemonic spatial practices.[14]

Resistance has been on socio-political fronts too as India showed a sharp rise in wealth and income inequality, which inevitably translates into spatial inequality. In Delhi where the G20 Summit was held last September, with a spend of Rs 4,100 crore,[15] but hundreds of houses and roadside stalls were demolished to “beautify” the city,[16] the affected and activists protested.

This prompted the Delhi Police to be prepared with chain and bolt cutters[17] signifying the return of the violence used to repress farmers’ protests and anti-CAA agitations.[18] This year also saw students’ protests across cities after corruption in various entrance examinations came to light. The notification of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act in March brought out protesters too.[19]

Photo: Sanjiv Valsan

The tactics, the future

The various resistance movements have, to paraphrase political anthropologist James Holston, forced “…the re-thinking of the social in planning”. Holston, author of The Modernist City, and the editor of Cities and Citizenship, wrote of an “insurgent citizenship” in Brazil’s “urban peripheries”. The extraordinary urbanisation of the 20th century, he noted, produced urban peripheries of devastating poverty and inequality in cities worldwide but “at the same time, the struggles of their residents for the basic resources of daily life and shelter generated new movements of insurgent citizenship based on their claims to have a right to the city”.

These are violent or peaceful, often constructive, and have managed with few resources but loads of commitment from resistors. Pune’s Vetal Tekdi example shows the fight over years in imaginative but peaceful, creative ways.[20] Bengaluru’s lake rejuvenation graduated from protests to constructive work besides forcing the civic body to stop projects.[21]

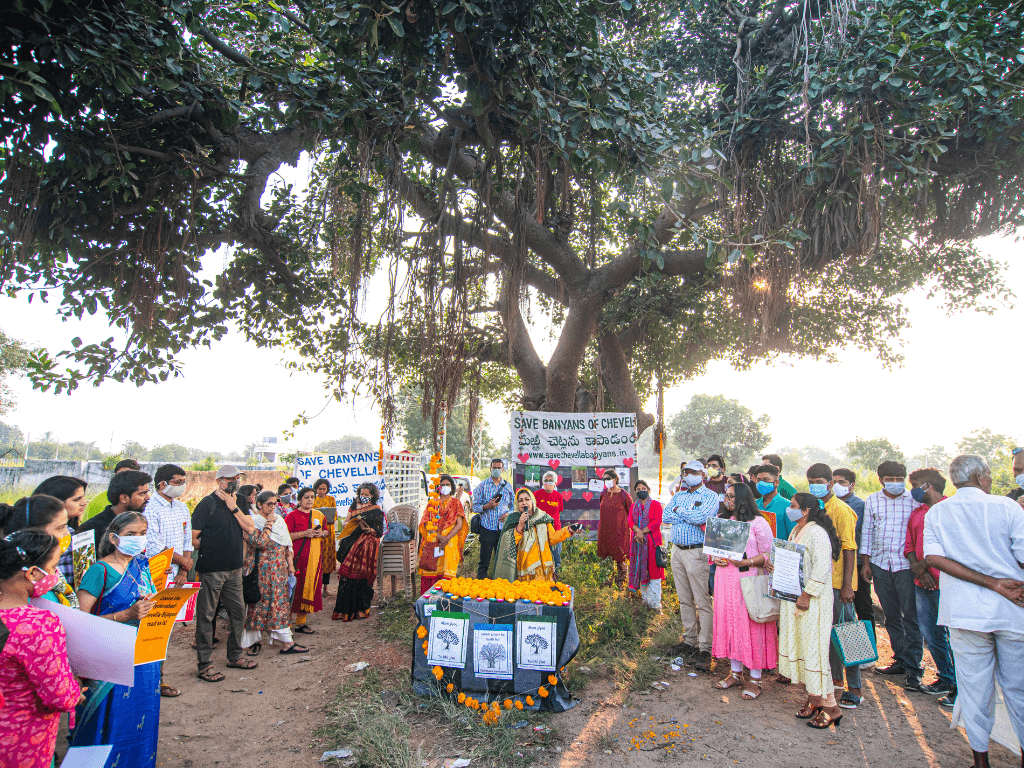

At times, resistance achieves partial victories like in Mumbai’s Irla Nallah Project or a temporary reprieve like saving the Chevella Banyans near Hyderabad. Environmentalists and architects in Juhu planned and supervised the cleaning of the filthy Irla Nullah and the construction of a linear park along its length, as a pilot project, showing the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation that nearly 300 kilometres of linear parks could be similarly built along Mumbai’s water bodies.[22]

Nearly 900 banyan trees of Hyderabad, many of them over 100 years old, were to be cut to expand National Highway 163. The protests since 2019 by the Save Banyans of Chevella led to the National Green Tribunal to direct the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI), last November, to minimise the loss of trees. This was an achievement. This September, however, the NHAI announced that it had got the clearances to build four lanes on the highway by retaining 393 trees and relocating 522. “We want the Environment Impact Assessment to be made public. We don’t know the details yet,” says Tejah Balantrapu, member of Save Banyans of Chevella.

Urban resistance has adopted various tactics. Tedious grunt work is sometimes expensive but committed people do it. What most agree upon is the need for a multi-pronged approach from the show of strength on the streets to battles in courts, running social media campaigns, using creative arts, working with political leaders and, of course, mobilising people. When signing online petitions is the norm, getting people out on streets to resist and protest is a challenge. But people’s collective power yields best results.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It took a year of such grunt work for residents in Mumbai’s Khar to have an underground parking project at Patwardhan Park scrapped. “Citizens objected to it. It’s an existing park, so it’s easy for people to understand the need to protect it. What’s out of their purview or area, people are not really concerned,” remarked architect Alan Abraham, who also filed a PIL to have the design of the coastal road changed to provide universal access to seafront areas. “The road has been open for over six months. No one has even once questioned, why can’t I walk near the sea? Why hasn’t a promenade been opened?”

Either court orders or people’s show of strength forces authorities to review or scale down projects. In Kolkata, junior doctors’ relentless roadside protests for safe workplaces, after the heinous rape-murder at RG Kar Hospital, brought the Mamata Banerjee government to its knees.[23] In Dehradun, locals coming out in large numbers against the massive tree-felling for road-widening projects saved thousands of trees when officials cancelled the widening of a stretch of New Cantt Road. “Dehradun had never seen such high temperatures (43.2 degrees Celsius in May). When the ACs were not cooling homes, it hit everyone in the face,” Ira Chauhan, member of Citizens for Green Doon, said. People joined the protests.

An observation many activists made is that resistance movements tend to be short-term and issue-specific, even if people in cities are able to rise above the quotidian demands of their work and long commutes; these do not necessarily transform into sustained or broad-based movements for the city as a whole. The opacity in the system is also a drawback, Abraham told Question of Cities, because projects do not come under public scrutiny at the conceptualisation stage. Despite this, committed environmentalists and social activists persist – with varying results.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“People come up with suggestions that planners, real estate companies and governments sometimes don’t think are important,” says Aravind Unni, urban practitioner and researcher, “Many policy changes happen through people’s movements and resistance.” Like Manch Sikkim, launched in 2023 by activists, architects, academics, IT professionals, designers, students is looking into models of “social entrepreneurship and social business to create sustainable livelihoods for all,” according to Kailash Pradhan who contested the general election but lost.

Everyday acts as resistance were exemplified in Mumbai’s Jaibhim Nagar basti in Powai. Demolished on June 6, the nearly 3,500 displaced daily wagers occupied nearby footpaths in temporary homes of bamboo and tarpaulin. A student-led group, Collective, arranged for food, building materials, clothes, and became their voice. How can we be safe without houses, the basti women asked. “This simple question exposes the deep cracks in our cities which refuse to count those living in slums or on streets as “people”. We demand safety for women but can it be meaningful without the demand of housing for everyone,” asked Huma Namal, a volunteer. Often, resistance movements reflect social divisions – women from the basti were prevented by Powai’s upscale women from joining the protests against the Kolkata rape-murder.

The politicisation of the young is a welcome spinoff of resistance movements. Resistance is political. The alternative, as Abraham points out, is to keep quiet and be a spectator.

With inputs from architect, illustrator and urban practitioner Nikeita Saraf

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she is concerned about Climate Change and is learning about sustainable development.

Cover photo: Credit: Citizens gather near the banyans of Chevella. Nature Lovers of Hyderabad