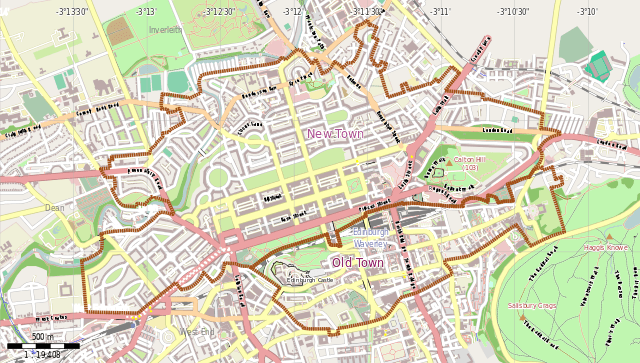

The year was 1887. The Royal Mile in the medieval quarter of Edinburgh was home to some of the worst slums in Europe, where outbreaks of cholera, food riots, unemployment, alcoholism, and crime reigned supreme. But it had not always been so. Old Town had once been inhabited by the wealthy and influential people of the city, who had by now moved to the neighbouring New Town, lured by its modern Georgian avenues and clean streets.

A young Scottish maverick named Patrick Geddes was observing these changes. Convinced that for any social change to happen, one had to live within the community, Geddes and his pregnant wife Anna, did the unthinkable. They moved to a tenement called James Court on Royal Mile, leaving behind the comforts of their home on Princes Street.

Surrounded by slumdwellers and working-class people at James Court, the newlyweds began to make changes to their environs. They set to cleaning and painting their own apartment and the external walls. They made boxed windows, with potted plants in them. The idea was to set an example. Aesthetically, the cosmetic alterations were pleasing to the eye; socially, they brought about a massive transformation in the neighbourhood.

Anna ran a sewing class at home for women and Geddes spoke the local Scots. They endeared themselves to their neighbours, who, gradually, started renovating their own flats. “The collective improvement brings with it a new atmosphere, that of a more collective and social life: the court is no longer a mere huddle of sooty hovels, pile upon pile, but a pleasantly varied and harmonious whole,” Geddes later said of the time.

This anecdote, right here, was classic Geddes: he took the living, breathing people of an environment into account, and got his own hands dirty. Later on, Geddes would go on to become an influential urban planning thinker and actor, but it was here, at James Court, that he began to reflect deeply on the nature of cities and the sustainable ways of preserving them. Over the next 20 years, he devised several social experiments that changed the face of Old Town.

Photo: Creative Commons

Almost all of Edinburgh’s Old Town in the late 1890s and early 1900s became Geddes’ laboratory. He stretched himself and the city well beyond the individual, by privileging community involvement over a top-down approach to urban planning. This signature style became a prototype for future generations of planners around the world. The experiments in Edinburgh formed the basis of his later projects abroad, as in Indore, Mysore and Chennai in India (working both with the enlightened rulers of India’s princely states as well as with the British Raj), and Tel Aviv (he proposed the city’s first master plan in 1925 for the Zionist Commission in the British-controlled Mandate for Palestine, 23 years before the creation of Israel).

Yet, in Edinburgh his name often draws blank stares.

But as the world grapples with the climate catastrophe, Geddesian ideas of conservation and ecology take on a relevance greater than ever before. Long before sustainability became a buzzword, Geddes believed that the environmental collapse was manmade, and the solutions should therefore be made by man too. At the first United Nations conference on the environment in 1992, it was agreed that citizen participation would be at the heart of sustainable practices going forward. This resonated with what Geddes had said at the beginning of the century: Think Global, Act Local, a motto popularised by Kofi Annan who took over as Secretary-General of the United Nations in 1997.

Geddes’ triad, conservative surgery

Patrick Geddes was no ordinary man. To whittle a polymath like him down to neat and singular definitions of profession or vocation would be unjust as he wore multiple hats effectively and simultaneously – town planner, sociologist, biologist, botanist, ecologist, and conservationist.

Perhaps his greatest contribution was his emphasis on the inter-connectedness between nature and culture, and how he saw “life as whole.” Deeply inspired by the French sociologist Frederic Le Play’s triad of ‘Place, Work, Family,’ (Geddes translated Family as Folk to encompass a wider swathe of society) Geddes devised what was then a radical approach to town and regional planning: integrating people and their occupations and livelihoods into the local environments they inhabited.

“Because he was coming out of this interdisciplinary culture, he was not siloed. He was constantly drawing these connections between people and cities, and botany, and plants. He was constantly alert to all these different fields and seeing the interest in all of them for learning,” the architect and architecture historian Robert Stephens told Question of Cities.

This is best represented by Geddes’ emblem of the three doves, signifying ‘sympathy, synthesis and synergy’. What he meant was that no project could be worthwhile if it did not engage on all these three levels: emotional, intellectual, and cooperative.

Around the time Geddes took up the cudgels for the Old Town, plans were afoot to pull down buildings that were old and dilapidated. This was unimaginable for Geddes, who believed that buildings fallen on hard times could be brought back to life by creative innovation and community participation. And this is where his revolutionary ‘conservative surgery’ method came into being. Simply put, conservative surgery meant: keep what can be repaired and let go of what was irreparable.

Photo: Creative Commons

So much of the architecture one admires at the gorgeous Royal Mile today would likely have vanished had it not been for Geddes. “We’re extremely lucky that Geddes did what he did,” Murdo Macdonald, author of the book Patrick Geddes’s Intellectual Origins, told me. “He saw the Old Town not as preserved heritage but as living heritage. For him, if heritage wasn’t alive and kicking, it wasn’t there at all,” Macdonald said. The buildings were not torn down, and are today, pretty much as he left them, put to commercial or residential use.

The living heritage idea is best illustrated in the Lawnmarket area on Royal Mile, where he embarked mostly on his private projects, without any formal help from the Town Council. Take for instance, Riddle’s Court, which sits at the foot of the castle, a stone’s throw away from James Court where Geddes and his wife lived. Built in the 1500s, this tenement was the address of royalty and influential aristocrats through the 17th and 18th centuries. By the time Geddes moved across the street, it was in a state of decrepitude. Around 250 slumdwellers lived at Riddle’s Court, crammed in tiny flats.

Geddes purchased part of the property and remodelled the building in keeping with his conservative surgery approach. Three years later, it was opened as a University Hall of Residence, one of the first, if not the very first such in Britain. It heralded a new way of looking at students’ accommodation.

What became of the slumdwellers who had lived in these Edinburgh buildings? This question was foremost on my mind, having come from Mumbai where displaced slumdwellers are often shafted in the name of development projects: I asked it of several Geddesian experts in and outside of Edinburgh and nobody seemed to know. The answer finally came in a book called Edinburgh – The Making of a Capital City, in a chapter on conservative surgery by Lou Rosenburg and Jim Johnson. It seems plans to rehouse them elsewhere did not quite materialise as previously envisaged, reminiscent of the Slum Rehabilitation Authority projects in Maharashtra. Could we see this as an early example of gentrification, a displacement of marginal populations proceeding alongside a well-meaning commitment to the comprehensive reform of urban design?

The garden as an ideal place

At Riddle’s Court, you can start peeling the many layers of Geddes’ mind. Walk in through the narrow gate and on the ground are engraved shapes of leaves, accompanied by Geddes’ famous motto: ‘By Leaves We Live.” Geddes embodied this philosophy. He said: “How many people think twice about a leaf? Yet the leaf is the chief product and phenomenon of Life: this is a green world, with animals comparatively few and small, and all dependent upon the leaves.”

Geddes believed that the “education of head, heart and hand”, best attained fruition in a garden. “He thought a garden was an ideal place to learn. It was where you picked up skills and attitudes towards nature, where you developed different ways of thinking,” said Walter Stephens, a Geddesian scholar and author of several books on Geddes.

Gardens, for Geddes, were also a vehicle to bring about social change. Before he undertook any project, he urged people to plant trees or lay out gardens. “When you’re organising cooperative gardens, you are giving people an innocent way of working out how to work together,” Stephens said. And this brings us to his other famous motto ‘Vivendo Discimus’ (by living we learn) which is carved above the archway leading into the inner courtyard at Riddle’s Court – which is today the Patrick Geddes Centre for Learning and Conservation.

A few hundred metres from Riddle’s Court stands the Outlook Tower, a property he purchased and christened, to demonstrate his vision of geography as a discipline that was interlinked with the self and the world. This building became Geddes’ headquarters – the Camera Obscura fitted at the top by the previous owner provided a glimpse of the city. For people to love and preserve their cities, civic education was crucial, Geddes believed. And so, Outlook Tower functioned as an educational centre, a museum, and a view of the world beyond Edinburgh.

Geddes himself took people on tours – starting first with the Camera Obscura, descending slowly down the floors, first through an Edinburgh room, then a space devoted to Scotland, then to Britain, Europe and finally eastern civilization and anthropology. His dream was to have the working class and the wealthy co-exist, creating a vibrant, diverse experience of the city. Thus, he embarked on one of his most impressive projects in Edinburgh – the Ramsay Gardens. Here, he willed into being a cluster of buildings where every flat was designed according to the specific needs of its residents. This project attracted the wealthy back to Old Town.

Photo: Creative Commons

Photo: Sukhada Tatke

Forgotten in the folds of history

Geddes transformed the field of urban design in terms of scope, scale, ideas and methods. If he is not remembered or sufficiently acknowledged today, it could be because his ideas have become so crucial a part of the architecture and planning community the world over, that it seems they always belonged. “Before Geddes we had architects just drawing plans of what they thought was the ideal city. Geddes came along and challenged that, saying, no, you can’t even begin to think about intervening until you understand the people, the history, the context,” said Robert Stephens.

Today, Geddes is barely known beyond the architecture community, even in Edinburgh which he transformed. He has had his share of critics but even they do not deny the influence of his ideas on later generations of architects and planners. A reason that Geddes does not invoke awe today could be that he defied pigeon-holes. He was a biologist and town planner, geographer and sociologist, weaving disciplines and borrowing from one to the other which makes him relevant to too many fields, at once.

Another reason could be that Geddes was not a particularly organised man; his methods were messy, his writing too dense. “Messy things generally don’t tend to become good bureaucratic systems. I would not be surprised, however, if there are remnants [of his thought] in community action and grassroots movements,” said Stephens.

After he passed away, the wars came and went and his ideas were forgotten. Every now and then, plans were floated to revamp Old Town, with the ‘conservative surgery’ approach left by the wayside. Thankfully, the plans never came to pass. Concerns in the architecture community changed during the interwar and post war years. Geddes was rediscovered in the 1960s and 1970s, mostly by architects and planners revolting against the brutal architecture, in particular the architect-pedagogue Cedric Price who was majorly influenced by Geddesian thought. “After he died, his ideas were considered too soft, too general, but when he was revived the environmental movement had taken off and his relevance was seen again,” said Walter Stephens.

There is one bust of Geddes in an isolated garden in Edinburgh; you could miss it if you did not go looking for it, unlike the prominent memorials to other great figures like David Hume, Walter Scott, and RL Stevenson. The Sir Patrick Geddes Memorial Trust in Edinburgh, consisting of Geddes scholars and enthusiasts, is trying to right the wrongs, attempting to raise awareness about the man to whom the city owes much.

Photo: Sukhada Tatke

Legacy in a painting

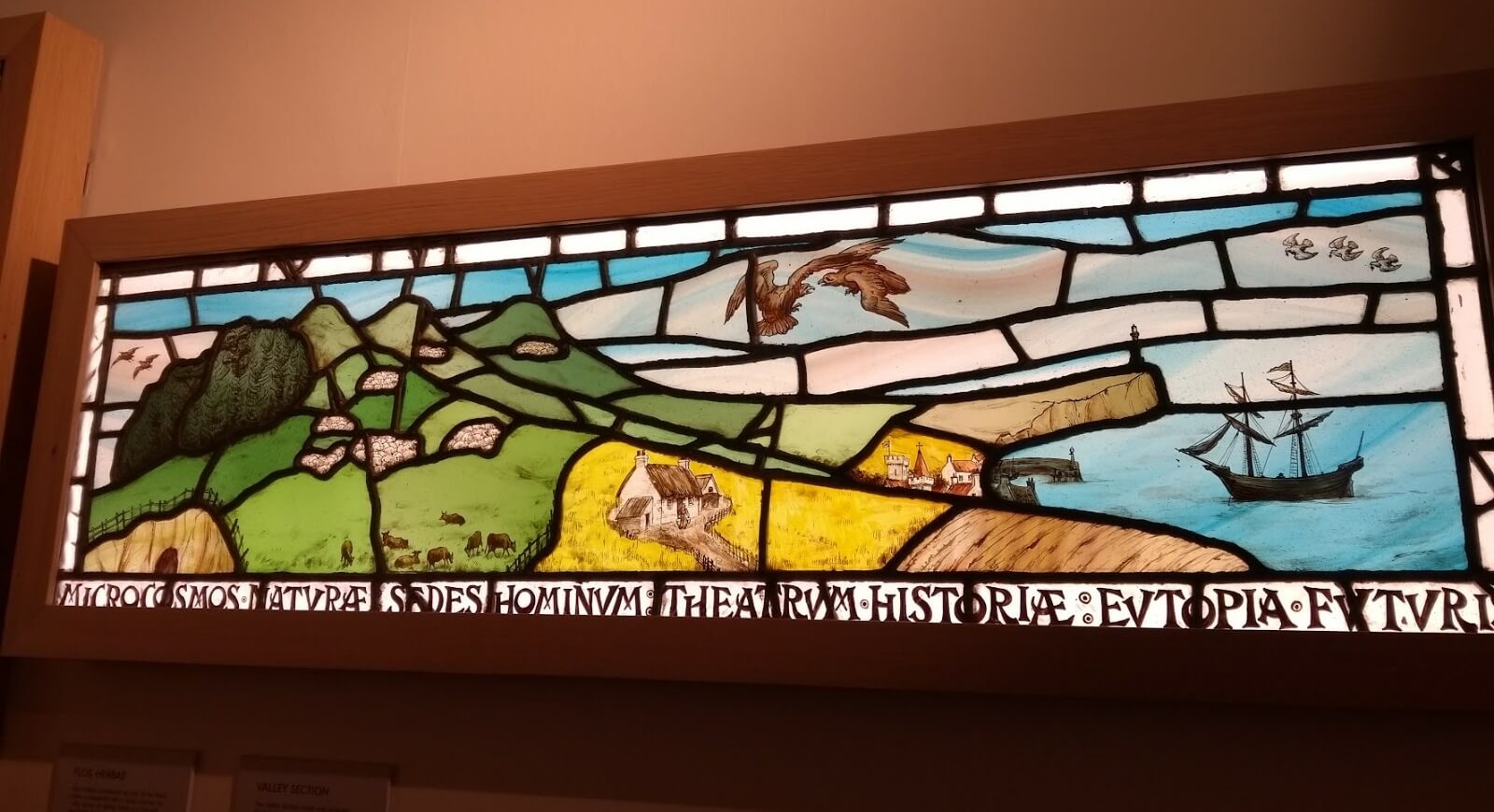

On a corner wall of Riddle’s Court, a stained-glass painting hangs like a frame. On it is an idyllic landscape, the ultimate diagram of sustainability: rolling green hills, the blue sky merging with the blue of the sea; birds, houses and agricultural land. This is the Valley Section, Geddes’ vision of an ideal city. At the base of the painting are the words: microcosm of nature, seat of humanity, theatre of history, utopia of the future.

This, right here, is Geddes in a nutshell. It is essentially a summary of his interdisciplinary views: you have the microcosmic nature, or the biological view; the seat of humanity, which is the sociological view. Then there is the theatre of history, which is the past. And finally, the utopian future, which is or should be a town planner’s prerogative.

And this is Geddes’ lasting legacy to us: his emphasis on scale, while never quite losing sight of community effort and civic activism; his awareness that the local-ness of the neighbourhood can never be removed from the larger region and environment of which it is a part.

Even though he advocated for a wholeness of human experience, for the coexistence of humans with nature, he did so with the knowledge that no human intervention could leave its surroundings undisturbed. So, while emphasising this coexistence, he was aware that this would have to be constantly recalibrated, re-examined, and with course correction built into the trajectory. Simply put: a city would have to be built around the abundance of nature, without reducing it to a decorative backdrop.

Sukhada Tatke is an independent reporter and writer based in Edinburgh. Her features and essays have been published in Indian and international publications including the BBC, fiftytwo, Atlas Obscura, Al Jazeera, and The Rumpus.

Cover photo: Creative Commons

There is 1 comment

A wonderful article, so relevant today, Geddes ideas of Cooperation, Sympathy, synthesis and synergy are sorely needed to renew our neighbourhoods.