Located in the western region of Bengaluru, this is the story of the Vrishabhavathi River, a key tributary of the Arkavathi. This research focuses on one of its origin points, the V-200, also known as the Nagarabhavi stream, which emerges from the Peenya Industrial Area. The journey is of a water body that becomes a drain, shaped by people’s everyday lives, shifting landscapes, and state-led interventions.

The Vrishabhavathi hasn’t always looked like this. What we see today is a narrow, blackened canal boxed in by concrete. It is the result of decades of layered interventions. Some were responses to pollution, others to flooding, and some simply by-products of the city expanding without room for water. Over time, what was once a seasonal stream has been redefined to meet the demands of a growing metropolis. Redirected, reshaped, and redefined.

In the early years, until the 1990s, the water body functioned as a holding system with seasonal flows. Locals called it a halla (pond), a clean and vital source used for bathing, washing, and even irrigation. It ran through largely forested areas, where people lived in close relationship with the water.

This began to change in the 1970s with the establishment of the Peenya Industrial Area. As factories multiplied rapidly, with Peenya becoming one of Asia’s largest industrial hubs, so did the volume of untreated industrial waste entering the river.[1] By the 1990s, visible changes had set in. The water turned dark, occasionally foamed, and had a pungent odour. The river, once essential, became something to avoid. A drain. A health concern.

By 2003, the laying of the sewage trunk line signalled a shift in how the river was being planned for. The approach was no longer about restoring it but about managing what it had become: a conduit for the city’s waste. Over time, infrastructural interventions such as stormwater drains, diversion channels, and culverts increased both in number and in scale. The river was encased on three sides, the bed and both side walls, using reinforced concrete. This was done to prevent flooding and ensure efficient sewage flow.

But in doing so, it sealed not just the river’s form but also its fate. Whatever remained of its ecological character was engineered out, flattened into a canal design. By 2024, the river is fully capped and concealed, overlaid with a playground. In the process, the river has disappeared from view, its flow buried and its waters fully contaminated (see below).

Illustration: IIHS Urban Fellows

Each of these developments from 1970, 2003, and the later phases of concretisation offers a clue to how the Vrishabhavathi reached its present condition. But more than isolated interventions, they reveal a deeper shift in perception. From seeing the river as a resource to a risk. From something to live with, to something to contain. These changing perceptions did not just reshape the river; they reshaped the relationship between people and the river. What remains today is not only a transformed river, but also a transformed idea of what a river is and what it ought to be.

River in violation and river being violated

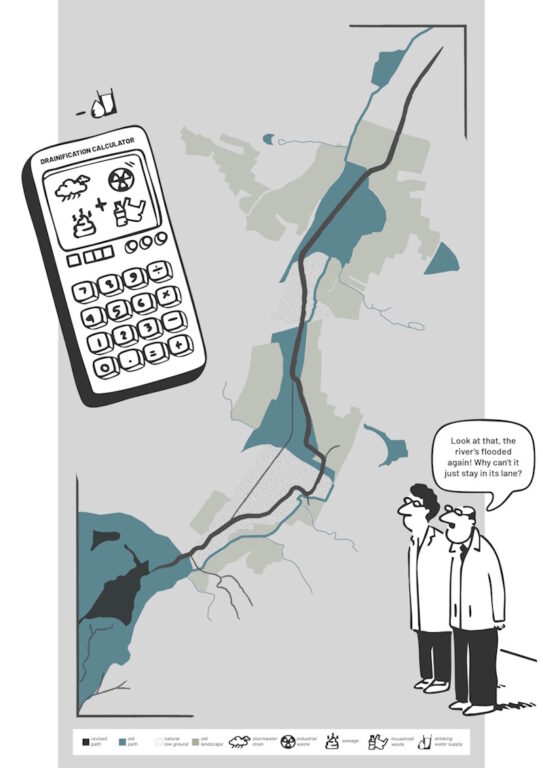

The narrative of a river in violation is our very anthropocentric way of thinking about rivers and their relationship with urban spaces. As Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha argue in Ocean of Wetness, when rivers flood or move beyond their human-imposed boundaries, they are often seen as transgressing their natural course. Flooding is framed as a violation, a disaster to be controlled.

But this perspective overlooks a fundamental truth. These boundaries are human-made. The river’s natural path has been redrawn to suit urban convenience, and when the river resists or responds, it’s the river that’s blamed.

Illustration: Fauwaz Khan

Perhaps, the river is not in violation. Perhaps it has been violated. Bengaluru, when looked at sectionally, reveals a landscape shaped by high and low grounds. The low grounds, once natural channels known as Raja Kaluves, would swell during the monsoon and connect a web of lakes across the city. It was a natural, complex and breathing hydrological system. Over time, these have been narrowed, covered, and re-engineered. Transformed from seasonal streams into perennial carriers of the city’s waste, including industrial effluents, domestic sewage, and everyday refuse.

As a Pollution Control Board officer from Peenya aptly put it, “If not for these wastes, there would be no river.” What was once a part of an adaptive, ecological network is now merely a canal engineered to carry the city’s discards. This is not a river ‘misbehaving’. It’s a river remade by human intrusion and interference.

If the only way rivers can exist in our cities is as carriers of waste, then what does that say about how we value them and their complex, alive ecosystems? Somewhere along the way, we stopped seeing rivers as living systems and started treating them as infrastructure, as drains, boundaries, and problems to be managed. Maybe it’s time we stop asking how to control the river and start asking how to live with it.

Temporary wins and long-term losses

Some interventions seem like solutions until time and geography begin to unravel their impact. To make sense of what has unfolded along the Vrishabhavathi, we need to look at it through two lenses: a temporal perspective (the now and what lies ahead), and a geographical one (from upstream to downstream).

This moment is the result of a chain of interventions, sometimes reactive, sometimes well intentioned, each addressing a concern but often at a cost. Some of these costs were visible and immediate, others slow and almost invisible. Some were acknowledged, others simply absorbed. While it’s tempting to critique the past with the clarity of hindsight, it is important to go deeper, to understand not just what went wrong, but why certain choices were made, what smaller wins were achieved, and why they seemed logical at the time. The absence of long-term vision and oversight has allowed newer, more complex challenges to take root.

Illustration: Fauwaz Khan

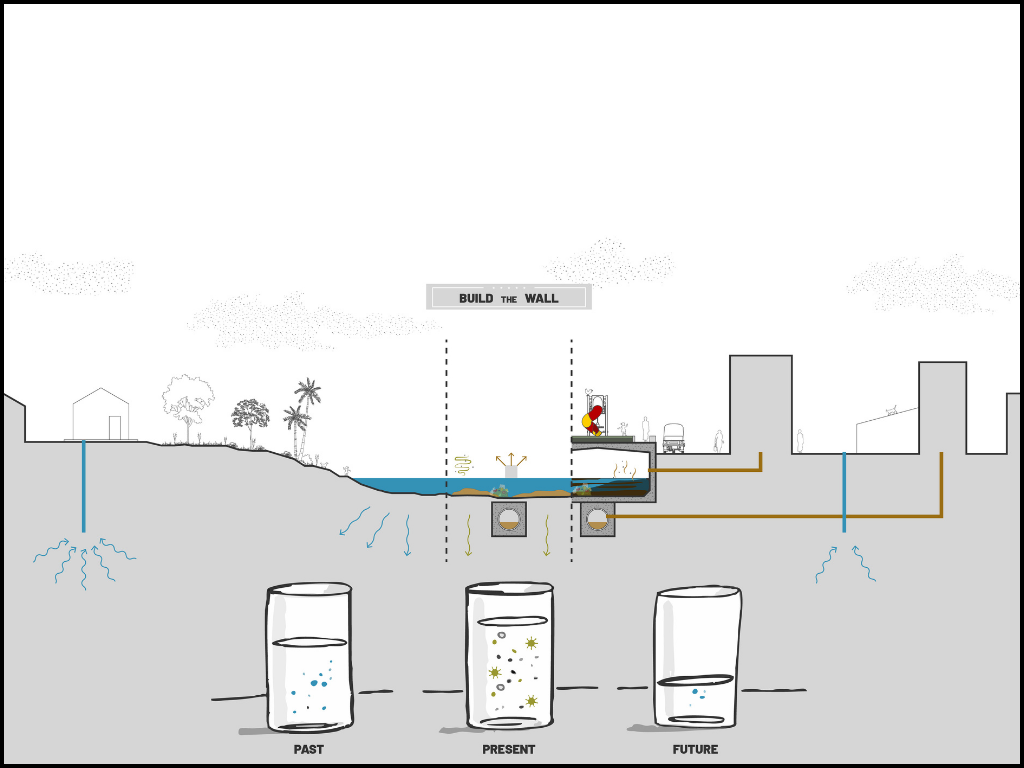

In the 1990s, the river began to visibly change due to increasing factory discharge. At the time, it was estimated that around 300 million litres of industrial and domestic wastewater were entering the Vrishabhavathi basin each day, with effluents coming from over 70 industries in and around Peenya.[2] In response, levee walls were built on either side of the waterbody in an attempt to contain the flow and reduce human interaction.

But the floor of the river was still natural. Slowly, the effluents and toxic water began to seep into the ground, making their way into the borewells that many depended on. In the Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY) Colony, located opposite Surana College, residents began noticing changes in their water. Madhu, who has lived there for 35 years, recalls, “If we sprayed the borewell water on the walls, it would turn them pink. If we touched it, it would sting and burn our hands.”

Eventually, the floor of the Vrishabhavathi was concretised too. What once flowed as a river became a canal, boxed in from three sides. And yes, the borewell water did get better over time, partially due to the concretisation or perhaps due to certain improvements in infrastructure to deal with the waste. But this ‘fix’ came with its own cost, one that is not immediately visible.

Bengaluru depends heavily on groundwater. While concretisation may have reduced contamination, it also slowed down the natural recharge of aquifers. Borewells have started to show signs of stress, and the groundwater table appears to be dropping. A new kind of crisis may not be fully here yet, but it is brewing. Now, it’s not one of quality, but of quantity. Its consequences are only beginning to surface, and are likely to be felt most by those with the least access to alternative sources. If left unaddressed, a water crisis awaits the city.

Lastly, seen from a geographical perspective, one realises that the river can be a flowing problem. While the concretisation of the waterbody may have offered temporary relief to residents living alongside it, such as less stench, fewer health concerns and reduced local flooding, it has pushed the consequences further downstream. The natural filtration once provided by soil and vegetation is gone. As the river flows, so do the pollutants, affecting downstream communities, farmers who rely on this water for irrigation, and ultimately, the city itself. These contaminants find their way back into Bengaluru’s food chain and drinking water through the Arkavathi.

Flooding too has not disappeared. It has simply shifted. The levee walls may have held it back locally but they have intensified it downstream, in areas such as Kengeri, Rajarajeshwari Nagar, and Bidadi. As recently as May 2025, after heavy rains, the Vrishabhavathi overflowed into Bidadi, around 30 kilometres downstream, carrying four truckloads of garbage into nearby villages.[3] What seemed like a solution upstream created new challenges elsewhere.

The futures

Video: Edited by Fauwaz Khan and Namitha Nayak

Bengaluru is currently witnessing multiple futures for its rivers. These competing visions shape how the city imagines and interacts with its water bodies. In Lakshmi Devi Nagar, the complete boxing up of the river has brought some relief to residents and has also created new land in the city, which is now used as a public space and playground. In contrast, the K-100 project led by the MOD Foundation, a rejuvenation initiative along a primary stormwater drain in the Koramangala Valley, is attempting something different. It seeks to create a more open and visible relationship with the water, challenging the “mori” label often attached to these urban streams. Rather than enclosing or concealing the flow, the project focuses on reconnecting people to it through design, public access, and improved infrastructure.

Meanwhile, the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) continues to direct its efforts at managing symptoms. These include raising wall heights, installing fences to block solid waste, and plugging “missing links,” referring to illegal sewage lines that discharge directly into the waterbody. But such measures continue to treat the river as a problem to be managed, not as a system to be restored. They offer control, not new imaginations, and do little to revive the river’s ecological or cultural life. More importantly, they fail to address the deeper harm these interventions have caused to public perception. Years of physical separation, coupled with increasing contamination, have widened the disconnect between people and the river, reshaping how it is seen, valued, or ignored.

What also remains missing across many of these visions is a recognition that the river can be a flowing problem, one that begins in the city but does not end there. While urban interventions tend to focus on what the river means within city limits, its journey continues well beyond, carrying with it both waste and consequence. In the city, it is managed as an infrastructure or nuisance. Further downstream, it becomes irrigation, livelihood, sometimes even drinking water. These are not separate rivers, but different realities of the same flow. Without acknowledging this continuity across landscapes, uses and responsibilities, any reimagination of the river’s future risks being incomplete.

Fauwaz Khan, Kirti Sharma, Namitha Nayak, Sanju Jayakumar, Simranjeet Kaur and Subhash Patil collaborated as urban fellows at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS), Bengaluru, to produce this research as part of the Practica project, from August to December 2023, under the Urban Fellows Program. The team extends special thanks to Juwairia Mehkri, Rasha Lala, Swati Surampally and Gautam Bhan for their invaluable support and guidance throughout the process. And would like to thank all the residents who generously shared their stories with us, offering insights that brought depth, nuance, and heart to the research.

Cover photo: Fauwaz Khan