Sana Shaikh, a second-year BCom student and a resident of Govandi in Mumbai, had never imagined making a film, let alone people watching and liking it. But there she was at the Govandi Arts Festival, quite proud to show her new-acquired skills at this creative expression.

“Around seven months ago, when we had our first meeting, several people wanted to learn and showcase their skills. But, there were kids who were scared and they said, “Govandi mein? Govandi mein kuch nahi ho sakta.” (In Govandi? Nothing can happen in Govandi). We saw them and got scared, but we wanted to be courageous and do this,” said Shaikh, who is passionate about films. “No matter what, we wanted to see the Govandi Arts Festival happen. It gave us a chance to form our identity,” she enthusiastically adds.

The five-day festival in February gave the children and youth of Govandi a fresh dose of confidence, but more importantly, taught them new ways of creatively expressing themselves, learning to work in teams, planning and participating in the neighbourhood festival on a scale they had not done before. Art, dance, rap – they did everything and turned a drab concretised parking square in between tightly-packed buildings of Slum Redevelopment Authority (SRA) into a carnival venue.

A nondescript lane off the Eastern Freeway buzzed with people, not only locals but others too. During the festival, it was easy to follow the crowd to an open plot at Natwar Parekh Compound in Govandi, the changed and charged ambience making it stand apart from its surroundings. The Govandi Arts festival, the first ever in this marginalised locality, put the spotlight on a place which people hardly visit or want to visit.

Govandi, a far-eastern suburb of Mumbai, is the site of several resettlement colonies. It also has the Deonar dumping ground, which deters people from living here.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey.

Remaking the suburb

Govandi’s youth did not know but they had contributed to a larger discussion of claiming – or reclaiming – public spaces. Residents here are mostly lower class self-employed people who were displaced, many of them violently, from their homes and livelihoods for Mumbai’s infrastructure projects. The inhospitable living conditions and lack of civic amenities in Govandi makes it seem a world away from say Bandra or Malabar Hill.

Zaheer Zulfikar Choudhary, a junior college student, used to be hesitant in answering where he came from but after being mentored for the Govandi Arts Festival, he is a proud member of Code 43, a troupe that’s defined by the area’s pincode. “We are refused admission to schools in Sewri and Wadala…It’s a big deal that the Govandi Arts Festival took place. Now, we are proud to say that we are ‘Code 43’ from Govandi,” he says with excitement.

In the process of creating the festival, the Community Design Agency (CDA) organised mentorship for the children and youth. Tasheer Khan, one of the mentors for rap, who organises cyphers at Marol Art Village, is proud of the children he has been able to mentor in Govandi. “The kids have grown by leaps and bounds. I have been inviting them to Marol Art Village for cyphers and they have been learning how to interact with fellow artists and producers. Code-43 is the face of Govandi. They will bring Govandi on the map of Mumbai,” says Khan, popularly known as Tash.

When the CDA, supported by the British Council, planned this festival from February 15 to 19, they might not have expected the surge of interest or curiosity that happened. People from across Mumbai made their way to Govandi to take in the festival. Nurturing talent in the area for well over six months, after months of earning their trust, saw a total of 37 youngsters showcasing their talent in photography, filmmaking, rapping, art and theatre through exhibitions, screenings and stage performances. The festival made Govandi more visible on the map of Mumbai.

The sea change

Across the length of Mumbai, at its southernmost tip that is the city’s old and largest dock, Sassoon Docks, the Mumbai Urban Art Festival took shape, later popping up at other venues across the city. In a nutshell, it sought to explore Mumbai’s relationship with the sea and reignite it for the nearly 2.5 lakh viewers who came to see the massive exhibition spread over the months of December through February.

The Sassoon Docks can be smelt miles away; it is usually filled with the clamour of fish being caught and brought ashore, cut and cleaned, sold and exported to places far and wide. The festival filled it with a different kind of energy, especially the lanes leading to the wet docks where Mumbaikars rarely venture even when they are allowed to.

For the festival, evocatively titled “Between the sea and the city”, the lanes were awash with a fresh coat of paint depicting life at the docks, its humongous buildings that serve as warehouses and ice factories had their facades painted artistically, depicting the life of the fisherfolk or the Kolis, among Mumbai’s first settler-communities.

In the excitement, it was possible to almost ignore the smell of fish, sweat and the sea, but the organisers St+art India Foundation supported by Asian Paints, had provided for a ‘smell stall’ with pleasant fragrances in case the stench became over-powering for visitors.

People from all over Mumbai came to take in the festival offering, see the exhibits and installations, engage with the interactive ones, hear the stories of people they usually do not interact with and learn about their lives. It allowed visitors to witness these stories in a safe space. The festival opened up the world of art to the Kolis and introduced them to the rest of Mumbai.

The exhibition explored this theme through murals, installations and lectures among other mediums including films, paintings, and dance performances. The Sassoon Docks housed installations in three buildings, of which two were called ‘Illusions’ and ‘Intuitions’. Visitors explored and questioned the relationship and the stories of the sea. Tapping into the mind’s ability to conjure things up were installations by artists such as Kiran Mahajan, who through their work deconstructed the myriad of connections and relations people have with the sea while looking at them through a variety of vantage points.

Tarini Sethi’s work focused on the ‘circus of illusions’ that our city builds to capture its inhabitants. Both installations spoke of the chaotic and unstructured character of the city’s relationship with the sea. The other immersive exhibit that tested the mind’s eye was Dennis Fabian Peter’s mixed media installation called FLOW.0, where innumerable tube lights covered the ceiling and their rhythmic switching on and off mimicked the constant motion of the sea waves.

Busting myths

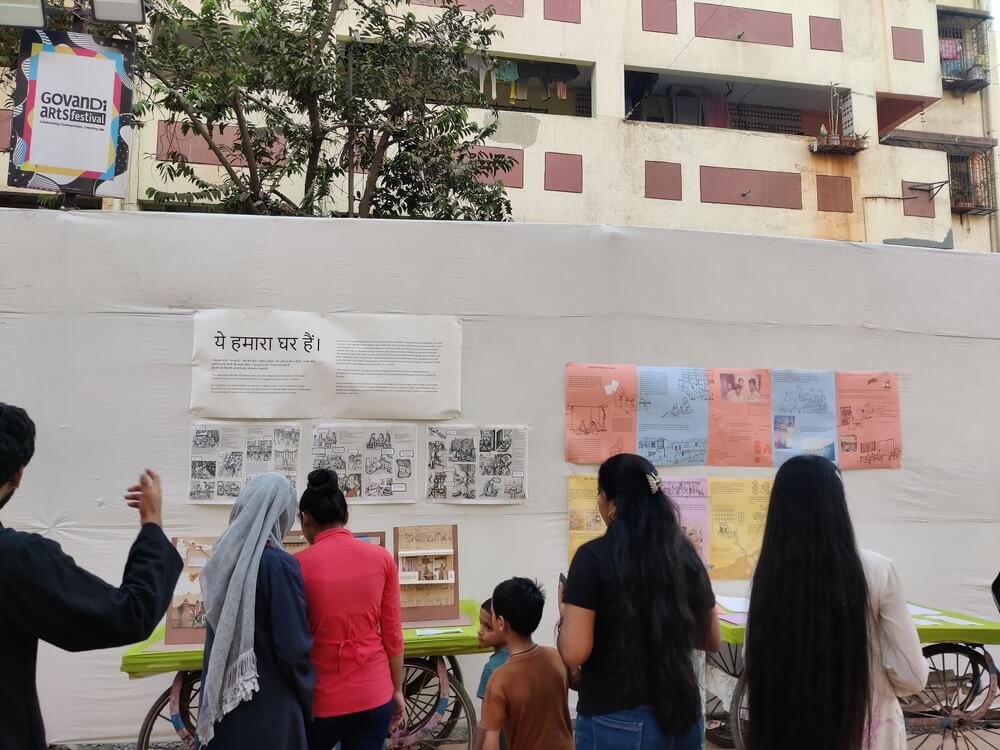

The students of the School of Environment and Architecture, Mumbai, spent several days with the communities at Natwar Parekh Compound, learning about their everyday stories, their cultural backgrounds, identities and challenges. This translated into a neighbourhood museum of sorts, ‘Yeh Hamara Ghar Hai’, under the guidance of Bhawna Jaimini and Rohini Singh of Community Design Agency.

“Coming from our privileged positions, there’s an absolute possibility of appropriation and othering,” said Rishabh Chhajer, who was part of the groups which worked on this. “All of us went with some presumptions and anxieties but they all vanished by the end of the first day. The method here was the conversation and reversing the gaze on ourselves. These conversations were charged by ethnography as a method of storytelling.”

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

The beauty of an art festival that unfolds in front of you, and the magic of the systematic process of the artists were a unique experience for participants of the Govandi Art Festival. The politics, if any, was at subtle levels and showcased the art as the residents approached it. The festival bridged the gap between people’s perception of hip-hop and its use as a means of expression. The ripple effect is that rapper-mentor Tasheer Khan has requests from other slum areas and non-governmental organisations to teach children.

Photo: Sohil Belim

The art of inclusiveness

What the festivals attempted to do was bust the myth that art and culture are exclusive and meant for a few chosen ones. However, when art steps out of galleries into the streets and the commons, it gathers far more interest and a sense of wonder. It lends itself to becoming a space that can hold the imaginations of several people at once.

In Govandi, children were busy making lamps for the lantern parade, there were workshops on mehendi and prosthetic makeup, musical shows were held until sundown and were open to all. In the Sassoon Docks, the immersive quality of the high-ceiling warehouses and the large, impactful installations allowed people open interpretation, introspection and rumination.

The exhibit that largely caught everyone’s fancy while also making an appearance on every social media platform, a large sheet that looked like a sheet of gold sequins in a striking blue-coloured room resembling the sea. Titled “Sea never dies” by Ghanaian artist Serge Attukwei Clottey, the gold sequins were actually cut-out squares of yellow gallon cans that supplied cooking oil which were repurposed as water containers by households in Ghana, and eventually were discarded, which blocked waterways and ended up in the sea. This installation was a mediation on the informal economic systems of trade and reuse, being understood through materiality and destruction of water resources.

French artist Rero took city-dwellers from acknowledging their relationship with the sea to literally coming face-to-face with their narcissism and hunger to fulfill needs that have caused them to selfishly kill the sea. ‘Vitamin Sea’, an ensemble of resin sculptures by auto-ethnographer Parag Tandel, from the Koli community, with its mostly dull and sometimes luminescent sea creatures ravaged by pollution and chemicals tells the story of the food of the Kolis based on the community’s history and shared experiences.

Tandel explains, “It was inspired by the shapes of phytoplankton, which is the food eaten by Bairidevi or the Whale Shark that used to be worshipped by the Kolis. Our tribe settled on the seven islands of Mumbai because we found food near the shore. The sea is important to us.” Tandel believed that the Sassoon Docks was the right place to showcase his work because the people of Mumbai don’t know much about the Kolis.

“People want to document us, but not understand us,” he adds. Tandel believes that he specifically wanted his art to be physically touched so that it could be experienced fully. “Our formal education does not provide us space to be able to sit quietly and think. People can witness inspiring thoughts in the form of images through festivals.”

Photo: Sohil Belim

Sakshi Gupta’s breathing metal scraps were a commentary on the city’s mindless usage and discard of materials that are junked beyond use. The exhibit had built a soothing lull soundscape for each and every space, however as we started walking towards one end of the warehouse a coarse and unmodified sound of dripping water took over. It was, “Pipes and Leaks” by Sajid Wajid Shaikh and Ronak Soni. The loud noise the installation made was corresponding to the loud and far more important questions the installation tries to make about the water infrastructure, deprived water connections and the right to clean water.

Sameer Kulavoor’s “metromorphosis” had a lasting impression on anyone who has ever looked at our city and wondered how elements keep adding to it and it never stops growing. Kulavoor, along with Sandeep Meher and team, built several miniatures of Mumbai’s buildings. Reminiscent of the paintings of artist Sudhir Pathwardhan, this installation tried to raise questions about the evolution of our urban landscape due to the constantly changing policies, political regimes and development codes. The project looks at the absurdities and the strange ways in which the city juxtaposes itself though all its anomalies.

Community for art

The visitors to the exhibitions also, in a way, became a community of people who took in art in ways and places they had not quite imagined. The exhibits and installations offered space for viewers to interact and figure out how they responded to the questions asked.

By making art relatively more accessible to everyone, the Sassoon Docks opened up art to be enjoyed, reviewed and judged by anyone and everyone who chose to interact with it. It almost presented itself like a social gathering, warmly welcoming people into itself and giving them a chance to find themselves within the art. In a city like Mumbai, this has its own value and relevance.

The Govandi event also brought home the idea that an area, usually dismissed in the mainstream narrative of Mumbai, could have its residents find creative expression in art forms they did not think possible – and have Mumbaikars come there to see it. As someone remarked, there should be more neighbourhood festivals like this one.

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Maitreyee Rele graduated from School of Environment and Architecture (SEA) in 2021, where she mostly chose to work on projects on a larger urban scale. She is interested in studying people, their cultures and the society in which they unravel. An unfathomable love for films, art and every other form of storytelling make up the rest of the being.

Cover Photo: Govandi Arts Festival/ Jashvitha Dhagey