Corporate professional Ulka Shukla, living in Kharghar, Navi Mumbai, for the past 13 years, has seen the greenery deplete. Massive infrastructure projects like the Mumbai Trans-Harbour link, the metro network, Navi Mumbai International Airport and commercial development of land[1] have meant axing of tens of trees. The increase in dust levels, from construction[2] and dumping of debris in wetlands and vacant plots are leaving an impact on trees.

Kharghar is one of the 14 nodes in Navi Mumbai, the city built from the 1970s onwards based on a master plan by architects Charles Correa and Pravina Mehta with engineer Shirish Patel.[3] Navi Mumbai, across the Mumbai harbour, has seen its population rise by a staggering 87 percent since 1991, according to the 2011 Census, and building density rise too. The green cover in the area has depleted – mangroves in Sector 17 and 21 in Kharghar have debris dumped on them, fires have destroyed hills in various parts, and the City and Industrial Development Corporation (CIDCO) itself axed 724 trees for a housing complex and golf course on the upmarket Palm Beach Road.[4]

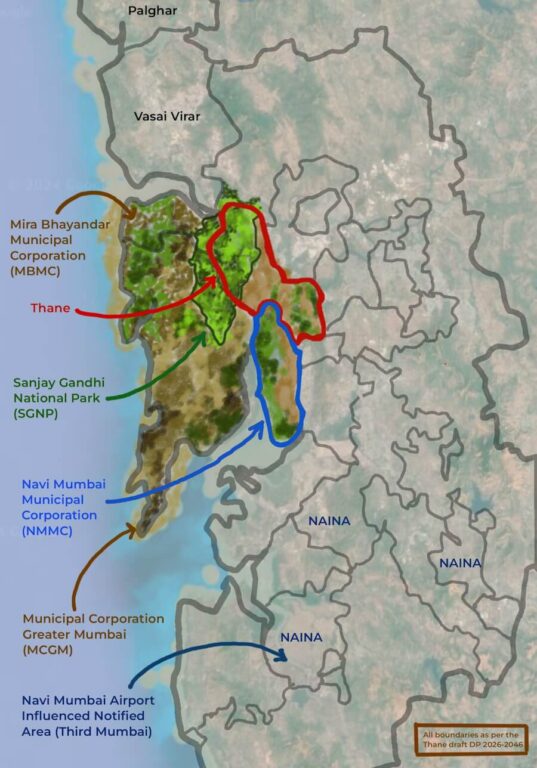

Map: Nikeita Saraf

Almost all the nodes – Vashi, Airoli, Ghansoli, Kopar Khairane, Sanpada, Nerul, Belapur, Kharghar, Kamothe, Kalamboli, Pushpak Nagar, Panvel, Ulwe, and Dronagiri – have seen green cover and wetlands shrink as urbanisation spread. The National Green Tribunal, in 2022, estimated that nearly 22 hectares of mangroves had been lost to development in only one taluka.[5]

Thane, one of India’s fastest growing cities that lies to the northeast of Mumbai and north of Navi Mumbai, registered a similar trend over the past decade. Its population was up by 35 percent, as per 2011 Census[6] and has been rising since. Its once lush-green cover, some of it in the Yeoor hills and beyond, is under pressure.

Of the total area of 128.3 square kilometres, the Thane Municipal Corporation (TMC) stated in its Draft Development Plan 2026-46[7] that about 39 percent is ‘non-developable’ which presumably includes green and open spaces. The DP does not explicitly factor in climate change or ecology. Only in 2024, Thane had a registered loss of 1,329 trees – or seven trees damaged every two days.[8] Clearly, in both the cities, the green cover is under duress. And it is the people who have extended themselves to save it.

Important fight

Navi Mumbai had huge parks, ample public and open spaces and dense greenery when it came to be. As the population increased, housing societies and office spaces were built and large-scale infrastructure projects started – besides the airport, there were roads, rail corridors and the golf course.[9] [10]

Navi Mumbai became a hotspot for real estate investment with 48 percent increase in the price per square feet in the last decade.[11] As its natural tree cover declined, the city saw the impacts of extreme weather events intensify. The impact of the loss of tree cover and wetlands on the city has been barely documented – a far cry from Barcelona master plan for trees 2017-2037[12] which approaches planning through the lens of trees.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

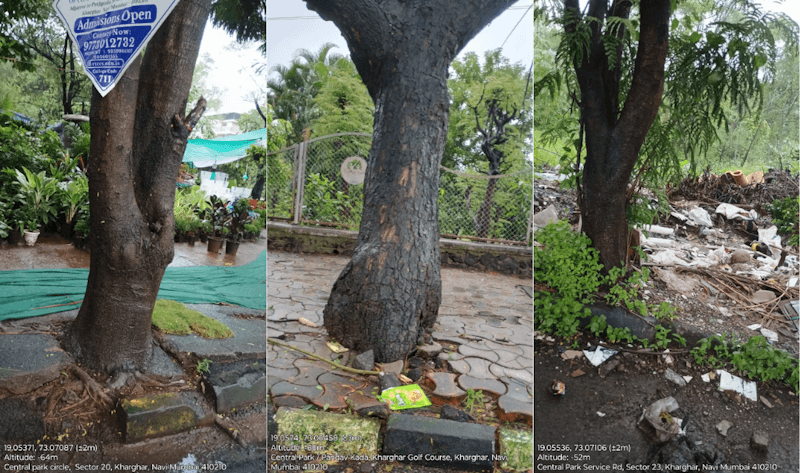

Environmentalists and activists made it their mission to prevent hacking of trees, getting them de-choked, and planting anew. Like Ulka Shukla in Kharghar, who first noticed trees in Mumbai’s Bandra Kurla Complex, where she worked, choked at their base with cement and tiles in 2019. After attending to them, she took the lessons to Kharghar, where she lives. Like others, she observed that areas without trees had water logging in the monsoon. It spurred her. She now requests people to send her photos of trees choked at base and canvasses with local authorities to have them de-choked.

“Cities around the world are taking down cement roads; we are building cement roads, pavements, and streets. Where will the water go,” asks Shukla. “I want people to get more involved and take this up with authorities. For us, to do this one by one will be a long process. There are thousands of trees in Navi Mumbai, in fact only in Kharghar, that are choked by cement,” she adds.

Urban trees are choked by concrete and/or tiles which prevent the aeration of their roots and percolation of water which, in turn, prevents trees from getting nutrients and minerals. They weaken, wither and perish. At least one metre of open soil around the tree trunk is needed, say experts. The National Green Tribunal (NGT), in a similar case about Delhi’s trees, stated: “They (the authorities) shall ensure that the concrete surrounding the trees within one metre of the trees is removed forthwith…and due precaution is taken so that no concrete or construction or repairing work is done at least within one meter radius of the trunk of trees”.

In Nagpur, it required a PIL to have trees de-choked and numbered.[13] But it’s not only Nagpur or Delhi or Navi Mumbai. Across India’s cities and towns, tree bases are being concretised or tiled under the guise of ‘beautification’.

As for the rise in tree cover that Navi Mumbai’s tree census showed – 78 percent in eight years[14] – environmentalists are livid. “We are not sure about the basis of this study, whether they have calculated even the few trees on the roadside and in housing societies. A small plant in a compound is not a tree. If the tree cover had really increased, we would not have had so much pollution. Also, most trees that CIDCO has planted are ones with no productive value or biodiversity. We need native trees,” explains BN Kumar of NatConnect Foundation

Photo: Ulka Shukla

Dharmendra Kar, a data scientist, combines his expertise with his passion for sustainability. As the founder of the WAY2 ISR (Individual Social Responsibility) Foundation,[15] and influenced by Sunil and Shruti Agarwal, wetland warriors in Navi Mumbai, Kar has planted 20,000 trees across schools, colleges, universities, hospitals, and government offices. “We have taken care of planted trees. Now, we want more people to join; few put in action, effort and money.”

Similarly, BN Kumar appreciates the authorities adopting the Miyawaki[16] approach at Kopar Khairane dumping ground.[17] “The per capita tree ratio may be on the rise but it’s not enough. There is no greenery in the Thane-Belapur Industrial belt,” he says. In November 2024, NatConnect moved the NGT to save 200 trees on a 300 square metre plot in Pawane.[18]

Thane story, same plot

Ghodbunder and Majiwada junction, two of the busiest junctions in Thane do not have a single tree along 19 kilometres of the Eastern Express Highway they cover. Ghodbunder was a forested area till the construction boom of Mumbai extended to Thane. Once only a connector between Thane and Mumbai’s suburb of Borivali, it’s now a city in itself with hundreds of residential buildings, commercial complexes, banquet halls, malls and retail outlets. The ecological price of this has gone unregistered.

In 2017, an alarmed Rohit Joshi filed a Public Interest Litigation against the rampant tree cutting and pushed for a tree census. Though mandatory every five years, the TMC had failed to do one after 2011. The census report, finally published in 2022, showed that trees had risen from 4,45,262 in 2011 to 7,22,426 in 2022[19] but the number of species reduced from 301 to 271.[20]

Here too, environmentalists are not convinced. “According to me, a 60-62 percent rise is impossible. In 2011, I believe the count was 5-6.5 lakhs, it’s now 7 lakhs. In fact, because of development, green cover has been destroyed,” says Joshi, “This needs to be challenged. The methodology of the mapping needs to be checked, for example, how they define a tree and whether it was the same in 2011 and in 2022, whether GPS was used.”

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

As per the Maharashtra (Urban Areas) Protection and Preservation of Trees Act, 1975, if trees are cut for construction, developers have to plant in compensation.[21] [22] For Thane, the Act mandates that if one tree is cut, 15 must be planted; for one transplanted, five new must be planted. Thane’s Draft DP[23] recommends it should be 25 indigenous trees for each tree cut.

It is also mandatory for each municipal corporation to have a Tree Authority with experts in forestry, agriculture, horticulture, and botany. Typically, developers get permission from the Tree Authority to chop trees. “For almost 40 years, karyakartas or workers of political parties have been appointed to the Tree Authority. They are definitely underqualified for the job,” says Joshi. Seeing this as the crux to save trees, he filed a PIL in the Bombay High Court which directed the TMC to dissolve and reconstitute its Tree Authority.[24]

Joshi, with others, filed another PIL in December 2024, objecting to a Ready Mix Cement plant set up in the eco-sensitive and protected Sanjay Gandhi National Park for the Twin Tunnel Project between Thane and Borivali.[25] Thane’s tree activists are also concerned about the ‘Sanskruti Art Festival’ every January that could affect trees as placards are randomly nailed in and trees wrapped in fairy lights and electrical decorations. Started in 2012, the annual art festival held along the Upvan Lake, one of Thane’s 35 lakes, now attracts thousands.

However, it’s not only activists at work. Purushottam Gupta, an autorickshaw driver, has been running the ‘Sadbhavana Hara Bhara Foundation’[26] since 2016. He used to water trees and plants as he drove, which gradually turned into plantation drives on Sundays. “We plant saplings in roadside spaces or replant plants that are dry. I started getting more drivers to plant trees. Every Sunday, we plant saplings; every evening, we water them. I keep a can of water in my autorickshaw for this. Until we plant trees nothing will change. Dust and pollution are in the air always, wells have dried up, groundwater has gone down,” he says.

Nishant Bangera, founder of MUSE Foundation, has been at it too. One of his initiatives was ‘Clean the Creek’ launched along with other organisations. He protested against the TMC inaction, in 2020, to stop the dumping of debris and garbage as well as erosion of mangroves in Kolshet Khadi.[27] Pallavi Latkar of Grassroots Research and Advocacy, Prof. Vidyadhar Walavalkar, president of Paryavaran Dakshata Mandal,[28] and Seema Hardikar, an educator and botanist, are among those working to sensitise people to protect Thane’s green cover.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The way forward

Environmentalists in Navi Mumbai and Thane suggest a two-pronged approach – zealously protect the existing tree cover to prevent cutting, concretising and so on; adopt and implement, by mandates if necessary, multiple ways to green the city by using methods that have been successful in cities around the world.

Ulka Shukla suggests the Miyawaki technique – the Japanese way to grow trees in a dense and mixed way – to green Navi Mumbai more. The method is gaining popularity but tree lovers have questioned the applicability all over.[29] Another step is to recognise and implement urban forest groves. A single tree standing is not enough, say activists, because of the ‘isolation effect’ in which a solitary standing tree can be weakened or unable to withstand the lack of moisture, intense dust and temperature fluctuations. Tree groves were a part of rural life, often worshipped and maintained; these can be implemented in cities, say tree activists.

Data, accurate data, is an essential step forward too. How many saplings planted, how many transplanted, how many fully grown trees cut down and for what purposes, in which areas of a city and so on are data points that are necessary for any protective action. Making this data public and available to all citizens is also crucial. It should not take an activist like Rohit Joshi to approach the courts for a tree census.

In 2023, the Bombay High Court ordered the setting up of a helpline to monitor the de-concretisation of trees.[30] Most people are not even aware of the helpline. Getting this to work will ensure people’s participation in planting, keeping track of their survival, and tracking tree axing. Plantation events as self-promotion for politicians or celebrities, activists say, must give way to substantive work.

At the centre of all this is the integrity and role of the Tree Authority in every city. It acts as the custodian of trees and it must not be reduced to giving permission for tree-cutting. Coordination between tree authority, municipal corporation, urban planners, environmentalists is necessary. Navi Mumbai boasts of verdant greens, flamingo-flocked wetlands while Thane has its forest and lakes. Without people’s efforts to protect the green cover, these may well become mere memories.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect, illustrator and urban practitioner, works with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons