The humble-looking Nishtha Rural Health, Education and Environment Centre building in Rakkar village in Himachal Pradesh; the 644 kms of bike paths in New York City; the US Embassy building in Tokyo, Japan; Masaryčka Building in Prague; the Paranur railway station near Chennai; Zero-Carbon Shelters, Pakistan; St Stephen’s Church at Cumballa Hill, Mumbai. These are some of the outstanding designs and architectural work by women which stand out in the male-dominated field. The famous Zaha Hadid (1950-2016) popularly called architecture “a man’s world” showing how difficult it has been for women in the field. In the limelight as Hadid was, or quietly behind the glare, women architects and planners have attempted to leave their mark. Some succeeded in carving a niche for themselves and also encouraged other women to pursue this line of work.

The woman in the photo above, Minnette de Silva, Sri Lanka’s first woman architect, had an Indian connection. The first to design a social housing project in the island nation and the first Asian woman to be elected an associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), de Silva studied architecture in Mumbai, knew writer Mulk Raj Anand, briefly worked for German Jewish refugee and architect Otto Koenigsberger, chief town planner of Bhubaneswar. In London, she met Le Corbusier, famous for planning Chandigarh city. In the photo from August 1948, dressed in a silk sari with flowers in her hair, as she always did, de Silva is seen with artist Pablo Picasso (left), sculptor Jo Davidson and American political commentator Albert E. Kahn at the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defence of Peace held in Poland. However, de Silva is hardly remembered in Sri Lanka.

At the young age of 21, Maya Lin won a public design competition to design the Vietnam Veterans Memorial (Washington DC) while still enrolled in Yale University’s undergraduate program. A stark, black V-shaped ‘scar’ on the ground, the design garnered backlash which led to Lin defending her design to the US Congress.[1] However, this first project put her on the map as she went on to design several others – like the Civil Rights Memorial – while also experimenting with land sculptures[2] and installations that bring attention to the adverse effects of climate change (Ghost Forest, New York).[3]

In India, women make up for a whopping 47.06 percent[4] of registered architects but this number drops as they climb the rank ladder. Of course, building sustainable and gender-sensitive cities should not have to fall upon women only; it should be the endeavour of every planner and architect. Even so, it is important to make women’s work visible in a field that easily invisibilises them. In this compendium, we are shining a light on women architects and planners — some known, others not — in an attempt to familiarise them and understand their work.

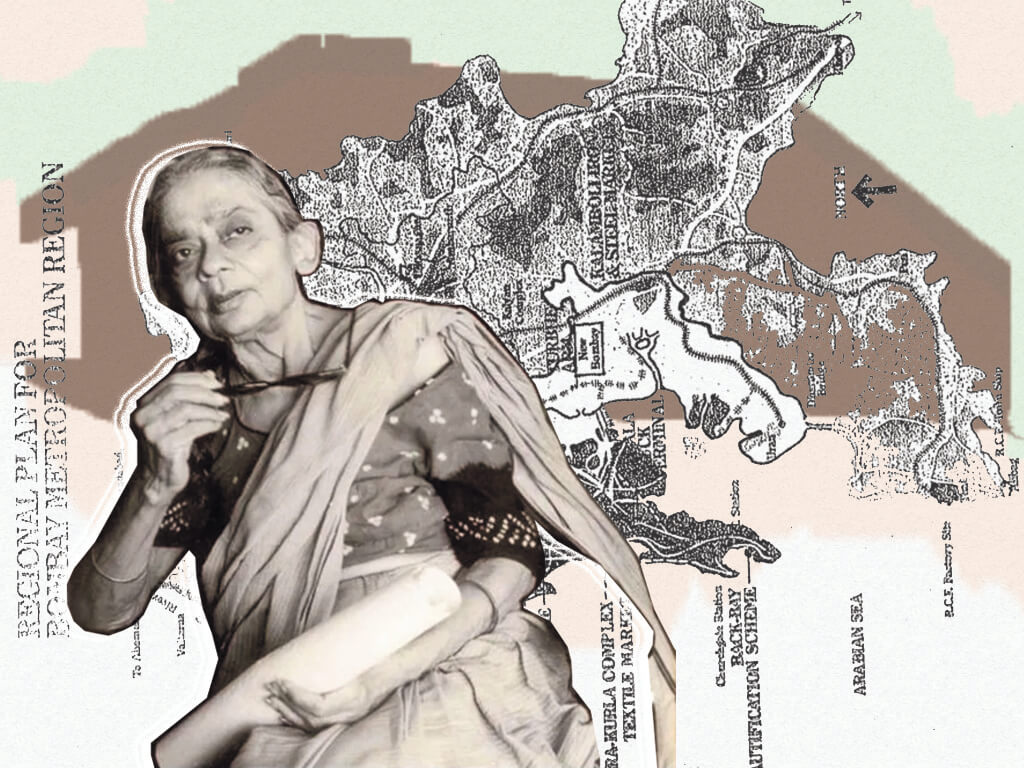

Pravina Mehta, India

“When a woman is truly committed to her career, when there is an inner compulsion, then she ceases to regard herself as a woman but only acts as a professional.” – Women Architects and Modernism in India: Narratives and Contemporary Practices by Madhavi Desai

Mehta wore many hats — architect, planner, political activist. Leaving her architectural education to fight for India’s freedom after being inspired by political leader and poet Sarojini Naidu, Mehta returned to the field after a short imprisonment for participating in the Quit India movement.[5] [6] She received her bachelor’s degree from the Illinois Institute of Design, and a master’s degree from the University of Chicago.

After two years of practice in Washington DC, Mehta returned to Mumbai and led a research unit documenting its multi-social and socio-economic issues. In her early career, she designed houses, factories, schools and institutions but unfortunately, most of these do not exist today. She was commended for her insight, knowledge and sensitivity to marginalised groups.[7] Along with architect Charles Correa and planner-engineer Shirish Patel, she worked on and finalised the plan for New Bombay — today’s Navi Mumbai.

They submitted the Draft Development plan back in October 1973 which proposed government initiatives for building new roads, bridges and land zoning. In a male-dominated profession of her time, she was outspoken[8] and believed that “a society which is committed to egalitarian values and to social justice should not allow gross inequalities to emerge in the housing facilities for the different sections of the population”. She was also a proponent for re-establishing the link between art and architecture, especially in the Indian-building context.[9] [10]

Delia Narayan ‘Didi’ Contractor, Dharamshala

“I’ve been attracted to architecture since childhood, but that’s not what women were encouraged to study in those days.” – Architectural Digest Feature (September 13th, 2017)[11]

Even though Delia Narayan Contractor (fondly referred to as Didi Contractor) has not been officially trained as an architect, her background in art and work using local practices to build homes led to her receiving one of India’s highest civilian awards, the Nari Shakti Puraskar.[12] She was born in Minneapolis, USA, to two artists, but lived across the world due to her father’s teaching role. Her journey in India began after marrying Narayan Contractor and living in Nashik, where they explored rural Maharashtra. But, she was inclined towards architecture since she was 11 years old.

After listening to a talk by Frank Lloyd Wright,[13] Contractor was inspired to create buildings that blend in with the surrounding landscape instead of contrasting with it. Her design philosophy used natural materials such as mud, bamboo, wood and stone, as well as local practices that are inherently climate-responsive.[14]

Her affinity towards natural materials is also evident in her 15 residential projects dotted around Dharamshala, where she resided.[15] This also meant that her structures simply required common knowledge of building practices instead of hiring ‘specialists’, which often seemed intimidating in the rural areas she worked in. In an interview,[16] she states that “eco-sensitive structures need to be built as per the season”, and that “one of the problems with contemporary life is losing our contact with the cycles of nature” – a philosophy practitioners today could adopt.

Perin Jamsetjee Mistri, Mumbai

“If men were compelled to do housekeeping, they would realise how avoiding corners, carved ornament and other dust-traps was an advance.” – Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects (January 1935)

Born in 1913 into a Parsi family of master builders, Perin Jamsetjee Mistri is regarded as the first woman to qualify as an architect in India. She was also the first woman member of the Indian Institute of Architects (IIA).[17]

Her family was progressive, and she went on to obtain her architecture diploma from Sir JJ School of Art. Her father had his own architectural practice, ‘Mistri & Bhedwar’, and specialised in industrial art deco style of architecture. While not much information is available regarding her early life, some of her biggest projects — the Khatau cotton mills in Borivali and St Stephen’s Church at Cumballa Hill — form the urban fabric of Mumbai.[18]

Her father’s firm went on to design the city’s iconic Metro theatre, among other structures, but documentation on Mistri’s contribution to other projects remains difficult to obtain. However, this does not take away from the fact that she was a ground-breaker for other women in a male-dominated profession.

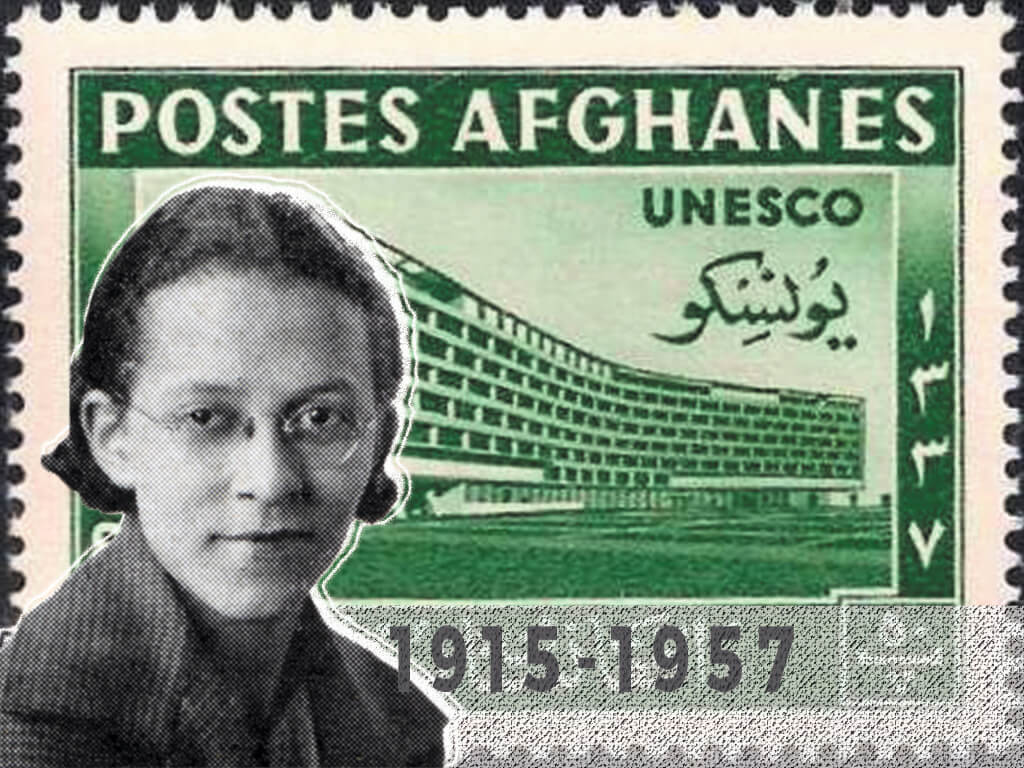

Beverly Lorraine Greene, Chicago

“I wish that young women would think about this field. Never did I have one bit of trouble because I was a negro, although there had been arguments about hiring a woman. However, the war has ended that, and Negro women in the postwar world will have a fertile field in architecture. I wish some others would try it.” – New York Amsterdam News (June 23rd, 1945)

As one of the first African-American women to be registered as an architect in the United States in 1942, Greene was also the first to earn a bachelor’s degree in architectural engineering from the racially integrated University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) in 1936.[19] As the only African-American and only woman member of the American Society of Civil Engineers’ student chapter, and an avid member of the university’s drama club, Greene supported the Chicago theatre by designing and painting sets.

The then mainstream media “made a practice of ignoring African-American professionals and intellectuals in general”,[20] but Greene went on to be hired by the housing authority after a masters from the same university. She assisted in designing the UNESCO United Nations Headquarters in Paris and some buildings for the New York University, but the biggest was an 8,000-unit housing complex in Lower Manhattan.

Almost 30,000 New Yorkers lived in this modernist garden city – ironically, Greene was not allowed to inhabit the residences she designed here.[21] Her record of being the ‘first’ for most areas in this field, Greene’s impact despite the race and gender disparities remains in her work even today.

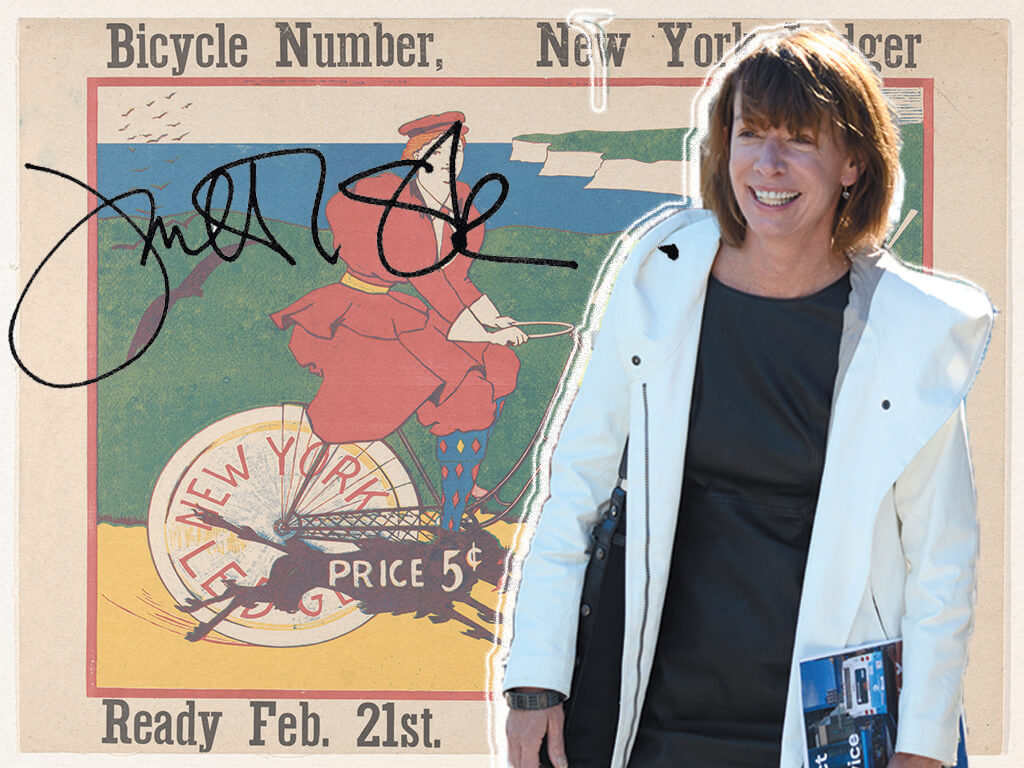

Janette Sadik-Khan, New York

“One of the good legacies of Robert Moses is that, because he paved so much, we’re able to reclaim it and reuse it. It’s sort of like Jane Jacobs’ revenge on Robert Moses.” – New York Feature: Honk, Honk, Aaah (May 15th, 2009)[22]

Ever marvelled at how pedestrian-friendly New York city’s streets are? We have Sadik-Khan to thank. As the former transportation commissioner of New York City Department of Transportation from 2007 to 2013, she pulled off a host of projects[23] [24] for the traffic-clogged city streets and made it safer for all.

She also led the creation of CitiBike, which is currently one of the most successful bike-sharing networks of over 12,000 bikes today. Despite being heavily criticised by media outlets for what seems like sweeping changes in the fabric of the city,[25] her bike and people-friendly initiatives were consistently widely supported in city polls. New York city now has 573 miles of bike lanes, with over 180 acres of former road space for motor vehicles converted to be used by bicycles and pedestrians[26] — a feat that could only be achieved under her leadership.

Norma Merrick Sklarek, Los Angeles

“In architecture, I had absolutely no role model. I’m happy today to be a role model that others follow.” – Pioneering Women of American Architecture[27]

Dubbed as the “Rosa Parks of Architecture” by AIA board member Anthony Costello when she was honoured with the AIA Whitney M. Young Jr. Award in 2008 , Sklarek was the first African-American woman to earn a licence to practise architecture in the states of New York and California in 1959 and 1962 respectively. Her childhood was spent in Harlem, where she was born, and was enrolled into the School of Architecture at Columbia University and graduated as the first African-American woman in her class.[28]

Discrimination in the field was high and she struggled to find work, but managed to secure one as a junior draftsperson in New York City’s Department of Public Works. Despite facing a series of obstacles owing to her gender and race, Sklarek managed to become the first African-American woman member of the American Institute of Architects in 1959.[29]

She believed that “architecture should be working on improving the environment of people in their homes, in their places of work, and their places of recreation”. A woman of many firsts, Skalrek was the first to be elected to the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects, and the first to co-own one of the largest women-led architecture firms in the United States. One of her biggest projects was designing Terminal One at the Los Angeles International Airport[30] — a building that continues to carry her story of success through hardship.

Sheila Sri Prakash, Chennai

“I take my role as an architect seriously because my thoughts and actions are bound to have a lasting impact on people, society and the planet. What I’m striving to achieve is holistic sustainability through design.” – Shilpa Architects Planners and Designers[31]

As the first woman in India to establish her independent architectural practice, ‘Shilpa Architects’,[32] [33] Prakash’s position as one of the country’s leading architects has led her to establishing various projects that focus on marginalised communities and sustainability.

Despite establishing her practice in 1979 in a field that was hostile towards women, Prakash persevered to create projects, like the Bahai Temple (Bihar)[34] and Cholamandal Center for Contemporary Art (Chennai)[35] that considered social and cultural aspects, preservation and conservation, as well as creating responsive ecosystems through architecture. She is one of 16 international expert members of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Design and Innovation (2011-2012),[36] contributing towards the Role of Arts in Society (2012-2013) — together, the council is dedicated to shaping a more resilient, inclusive and sustainable future.

In 1987, Prakash was recruited by the World Bank and HUDCO to create low-cost housing for the socio-economically underprivileged. She developed a ‘Reciprocal Design Index’ that prescribed design metrics for sustainable design[37] — her Reciprocal House went on to win an award and be replicated across South Asia.[38] She also founded the Reciprocity Foundation[39] to “facilitate appreciation of the concept of Reciprocity as a responsive eco-system of urban development that is holistically sustainable”.

Her firm has also been a member of the Indian Green Building Council, pioneering environmentally sensitive and socioeconomically sustainable design with LEED certification. She believes that “space can make or mar the quality of life”[40] and through the years, Prakash’s 1000+ projects[41] have greatly contributed towards sensitive architectural practices.

Yasmeen Lari, Pakistan

“You must believe in yourself, in your passion, your creativity and your ability, because you know in your heart that biases of age, gender or the colour of your skin have no relevance.” – Architectural Review (September 15th, 2020)[42]

The title of being Pakistan’s first woman architect is not to be taken lightly – Yasmeen Lari established herself in the field at the young age of 23. Today, after over 40 years of practice, her contributions to the fields of architecture, humanities and social work will remain relevant for years to come.

She pioneered Pakistan’s first housing program in 1973, Angoori Bagh,[43] which proposed to build 6,000 houses for medium and low-income families. Her projects like Zero-Carbon Shelters[44] and the Makli Barefoot Ecosystem[45] embraced traditional building materials and practices, while employing local labour to build low-cost sustainable structures.

Over the years, her architectural practice intersected with social justice, as she also went on to be a co-founder of Heritage Foundation for Pakistan in 1980, a humanitarian group, with her late-husband, Suhail Zaheer Lari. Her efforts to better lives did not just remain within the field of architecture — she also designed a fuel-efficient chulah, which did not produce hazardous smoke that endangered women’s health.[46] [47]

Since 2010, Lari has dedicated her knowledge towards building more than 50,000 homes for humanitarian causes, helping victims affected by earthquakes and floods in Pakistan.[48] [49] Emergency shelters are now her top priority, and her shift from architectural projects for commercial international clients to projects for humanitarian causes is especially noticeable in today’s climate change-affected vulnerable world. She is currently involved in rigorous efforts to build one million flood-resilient homes in Pakistan.[50]

Suhailey Farzana, Bangladesh

“Within each of us resides an architect…Every woman holds a unique vision for the architecture of her house, seeking a harmonious blend of functionality and aesthetics.” – The Business Standard (December 20th, 2023)[51]

Suhailey Farzana is a community architect who enjoys the process of co-creation. One of her co-anchored initiatives is ‘Sobai Mile Jhenaidah Gori’[52] aims at transforming the town of Jhenaidah by engaging the community in planning and execution, along with government organisations and other architects. Under the initiative, their project ‘Urban River Spaces – Jhenaidah’ won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2022.[53]

The community-led initiative for creating public space along the banks of Nabaganga river yielded positive results for both[54] [55] the ecologically sensitive river edge as well as the 2,50,000 residents who live around it. Apart from contributing towards the project, residents, primarily women, are also encouraged to be involved in designing their own homes.

In 2013, she co-founded Platform of Community Action and Architecture (POCAA)[56] with the aim to create a network of people involved in community architecture. As a member, she worked with slum populations in documenting their homes, and subsequently contributed to housing projects designed by the National Housing Authority of Bangladesh, the World Bank and the Brac University. Her direct involvement with communities and a design philosophy that includes them at every stage have ensured that her architectural background is a tool to ‘facilitate people’s dreams and aspirations’.[57]

This is, by no means, an exhaustive list; it is more an indicative one to inspire you to look for women who might have faded into history despite their work in architecture and planning. It is important to relay these women’s stories and experiences for multiple reasons — first and foremost being to document their efforts for generations to come. With an insight into Perin Mistri’s sketches for Mumbai’s prominent buildings, a peek into Urmila Eulie Chowdhury’s contribution to Chandigarh’s city planning, we would have a better understanding of the involvement of women in the process of making cities what they are today.

Cover photo from Wikimedia Commons: Architect Minnette de Silva with Pablo Picasso (left) at the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace, 1948.

Illustrations: Shivani Dave