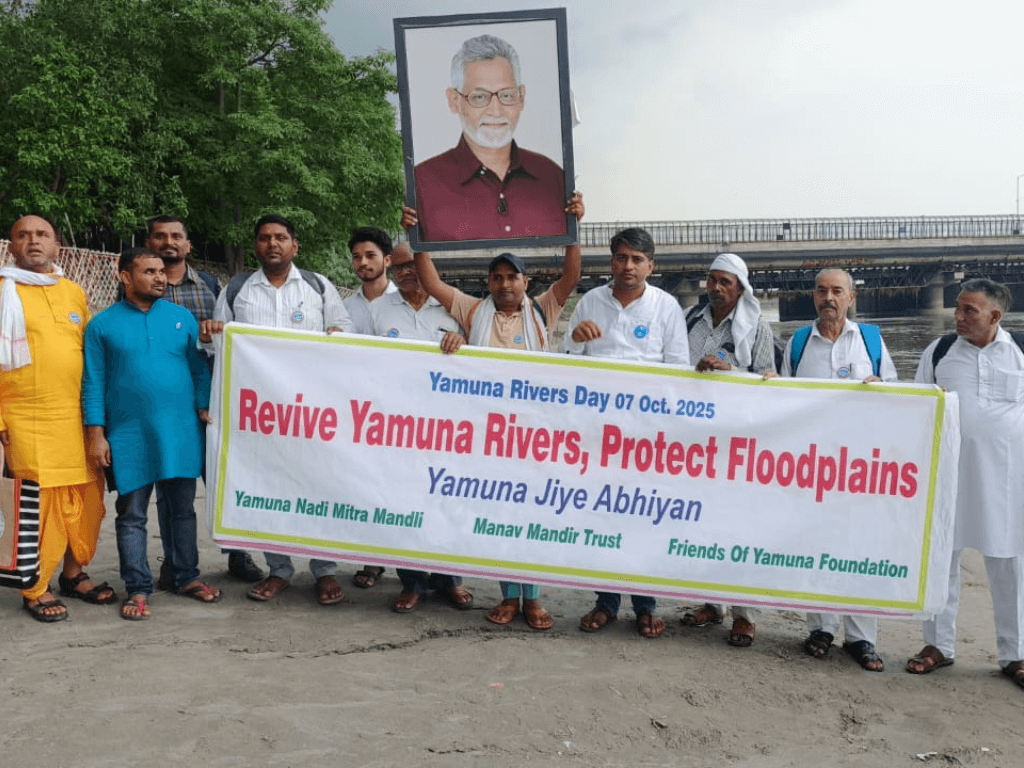

Over the decades, people in Delhi-NCR have mounted campaigns and fought battles, in the courts and on the riverfront, to save the Yamuna from deterioration as well as restoring it to health. Organisations and collectives like the Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan led by the late Indian Forest Service officer environmentalist Manoj Misra, WWF India, Friends of Yamuna, Earth for Warriors, Drishti Foundation which did biodiversity mapping backed by groups that led regular clean-up drives, organised human chains and continued with awareness campaigns in the face of fatigue, various students and voluntary residents’ initiatives have kept the pressure on the authorities for the ecological integrity of the Yamuna.

There have been a multitude of activities and relentless use of all legal measures available, including petitioning the National Green Tribunal (NGT) which directed a phased rejuvenation of the Yamuna in 2015, among other significant wins. From activities like the Yamuna Sansad, the Nadi Mitra Mandali groups in many villages to connect people to the river, educational campaigns and workshops in schools to the research studies which fed into the on-ground work, constant monitoring of official decisions and activities about the Yamuna, and sustained litigation, people have been the warriors of the river – for the river.

It was this movement on many fronts, sometimes coordinated and at other times chaotic, that managed to stall major projects like covering up stormwater drains and elevated road construction without environmental studies or persist in questioning others like the Millenium Bus Depot and the Art of Living festival. The Millenium Bus Depot, which was constructed on the Yamuna floodplains in 2011 despite protests and which the Supreme Court ordered removed, has been earmarked by the Delhi Development Authority for the Yamuna Riverfront Development Project.

While Misra’s passing in 2023 left a void in the larger movement, others like Bhim Singh Rawat have kept up the momentum – he spoke to QoC on how to save the Yamuna floodplains[1] – and many other less-known activists have picked up the gauntlet since – driven by their desire to see the Yamuna in Delhi rejuvenated

Pankaj Kumar

Climate activist

“I am from Bihar. I used to sell vegetables on footpaths in Noida. In 2015, I joined a multinational company and worked till 2022. When I went to the Yamuna for the first time around 2018, I felt bad because I had never seen such a dirty foamy river. I felt I should work for the Yamuna.[2]

I used to launch awareness campaigns showing plants in water containers connected to an oxygen mask — the message was plants are our oxygen cylinders. This campaign took me to Yamuna.”

“I founded Earth Warriors in 2019. We have a weekly cleaning drive on Kalindi Kunj Ghat, and conduct Yamuna Samvad where we talk about pollution, river health and other similar topics. Besides Delhi, we have covered about 12 states across India talking about wastewater treatment plants, Sewage Treatment Plants (STP); we check the water quality at outlets, we do research and publish reports, we analyse the reports that pollution control boards put out. We are also planning to launch a Citizens’ Laboratory which will carry out water testing for drinking water and publish reports that will be free to access for everyone.”

“I used social media to upload the campaigns and this helped more people to connect. Gradually, in one place, people saw that some cleaning work was being done, STP was put in, and teams formed. The organisation is independent and runs on donations; we work in teams – a research team, a reports team, a legal team.”

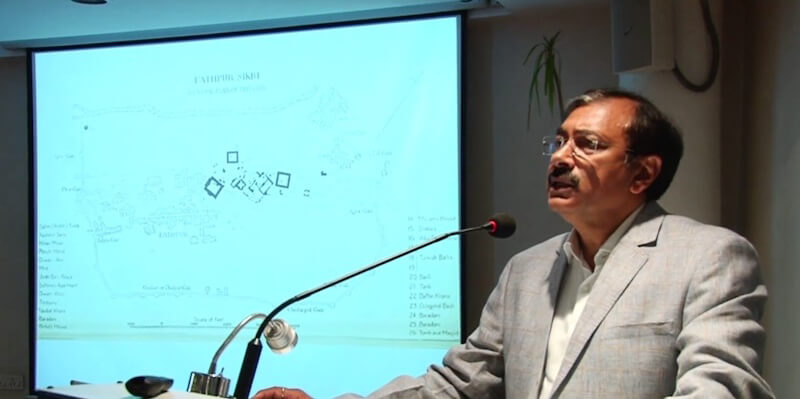

Manu Bhatnagar

Urban and environmental planner, Principle Director, Natural Heritage Division, INTACH

“I started working on water issues in 1996. The team worked on water policy, lakes and wetlands, river conservation, wastewater treatment and so on. We have done water policy and planning in Delhi and Yamuna figures in a big way.[3] We have not fought on-ground for the Yamuna but generated ideas for river conservation, conducted studies including one on the biodiversity of Yamuna in Delhi and Upper Yamuna.[4] We are now conducting one on the Yamuna Corridor examining the natural, cultural and architectural heritage.”

“Untreated water can be treated with bioremediation or nature-based solutions; these make a lot of difference. The water policy states that there should be more focus on recycling the treated wastewater, so that we take less water from the river. Pollution is an issue but the real issue is the flow in the river. It is very low. In the upstream, water is extracted from the Okhla Barrage and downstream from Wazirabad Barrage.[5] Downstream, the water flow is very low, increasing the concentration of pollution. The biodiversity of the river decreases; fish populations decrease, dish sizes are stunted, and other organisms diminish.”

“Maintaining the flow is more difficult than controlling pollution. We have made a regulation that the margin of phosphate in detergents should be reduced because it’s not easy to treat phosphates in Sewage Treatment Plants. It’s the beginning of the pipeline solution and, when enforced, will make a difference to pollution levels.”.

Nishant Pawar

Nature photographer, cyclist, environmentalist

“I live in Badwala village, Uttarakhand along the left bank of the Yamuna. Through Bhim Singh Rawat and the late Manoj Misra, a retired Indian Forest Service officer who ran the Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan (YJA).[6] I was connected to the Yamuna. Now, I have my own school, Rainbow Children’s Academy, near Dakpathar which is along the left bank of the Yamuna. We set up the Yamuna Eco-Scholar Club and the Nature Nurturers Club in our school for awareness activities. For example, we conduct plays which tell us how people are exploiting the Yamuna and other rivers. We do nukkad nataks, poster-making competitions, awareness drives on the riverbank mostly involving children. This works connects the river with the society.”

“Some actively participate and want to understand, others come to shoot photos or take the mic, but the positive factor is that our students who now study in colleges and universities participate in events and organise such movements elsewhere. For example, the movement in Dehradun to save the Khalanga forest.[7] When the government ordered it cut down, many of our ex-students actively participated.”

“I also do nature photography and I have cycled to Yamunotri – about 150 kilometres from our place – twice. I visited places in Uttarakhand such as Haripur, Dakpathar barrage, Juddo dam, Hathiyari dam. There is a huge mine in Haripur and the mining activities have destroyed the flow of the Yamuna river. The dam construction is the biggest problem for the river and the aquatic life in it. How will the river survive? Crocodiles used to live in the Yamuna, there was a lot of aquatic life; it is completely over.”

Vikrant Tongad

Greater Noida-based environmentalist and activist

“My village and my childhood were closer to Hindon, so Yamuna too is not far from us. I realised in 2010 that the situation of Yamuna and its major tributary, the Hindon, had been worsening. Unregulated underground water was being extracted from their floodplains. Ground water feeds the river, and during monsoon, the river feeds the ground water. If you extract water from the flood plain for industrial, domestic or other purposes, then how will the river remain alive when there is no rain?

“In 2010, I created a youth forum that would react to immediate environmental damage or would help people. We planted more than 1 lakh trees across Greater Noida and are maintaining them; since 2014, we have restored more than 10 water bodies on the floodplains of the Yamuna and Hindon. Jal Shakti Abhiyan amplified the water body restoration work. We have filed more than two dozen petitions on different environmental issues in the National Green Tribunal. We are working on the Yamuna in Delhi-NCR on ground water, tree plantation, water body restoration and saving the floodplains. There should not be any untreated drain emptying into the Yamuna. We stop floating garbage from flowing into the river by installing traps and dividers. The forum is continuously talking to the authorities to install trappers. Our work has been inspired by Manoj Misra and his Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan.”

“The first thing is to make farming sustainable along the Yamuna. Our group talks to farmers and also works with local communities to stop illegal mining which happens upstream (Haryana border) and downstream (Uttar Pradesh border). Directly and indirectly, we keep raising the mining issue. Downstream, as we raised our voice, Durga Shakti Nagpal’s[8] crackdown led to a significant reduction in mining activities. In Delhi and Noida, we are working for the restoration of the water bodies. If the water bodies, green areas and wetlands are conserved, only then will the river survive. The underground water is pumped and sold illegally – an issue we have been fighting since 2010 in the National Green Tribunal. On the banks of the Yamuna and Hindon, where green areas are available, we are developing urban forests.”

“The public should know the value of Yamuna. In Indian civilisation, the importance of rivers is philosophical but our rivers are the most polluted. Their state is so bad that people think that we have no direct connection with the rivers. Saving rivers has not been a priority because people think that they will get water anyway but people should understand that they are the custodians. River pollution is not just an environmental problem, it’s a social problem.”

Photo: Farukh Choudhary

Farukh Choudhary

Mandawar village

“My village is Mandawar in Shamli district, Uttar Pradesh, about 2 hours drive from Delhi. I am from a small farmer’s family but I am fond of politics; I have contested for village head position, district council and so on. I advocate against mining because it leads to many problems like pollution and water shortage. We noticed this when there was a mine in our area. I used to work with Bhim Singh Rawatji on the Yamuna issue. We brought a team to Jalba Chowk for this. We have talked to the villagers but, as soon as the excavation started, they started opposing us, not the excavators. As the problems increased, we reached out to people from neighbouring villages too.”

“With guidance from Bhim Singhji and a lawyer, we approached the NGT with all the documents possible. It took about a year to a year and a half from May-June 2024. We won in January 2026. Since it has been closed, the water is flowing. In this season, usually there’s very little water in the river but now it’s flowing. The mining has destroyed farmland too but it will be good now.

Cover photo: Protest at Yamuna Ghat, Delhi. Credit: Farukh Choudhary