Goa, supposedly India’s favourite tourist destination, conjures imagery of beaches, verdant fields, and lush hills. Few can, therefore, believe that this small state that received approximately seven million tourists in 2022 is one of the most urbanised states of India.[1] I argue that Goa presents an alternative urbanity, which is ecologically more resilient and fosters a higher quality of life. This alternative urbanity is what gives Goa its unique charm. However, Goa’s alternative urbanity is also rapidly being undone.

Forces at play are reconfiguring the state into a hyper-urban system comprising a gross mixture of large gated real estate projects and exclusive high-end tourist enclaves braided together by a network of grandiose transportation networks. Much of this nuevo development is carried out with scant regard for ecological systems. This essay argues that Goa’s alternative urban fabric resulted from land-use planning, namely regional and urban planning that began as early as the 1980s, is why Goa offers a high quality of life. However, it has also attracted the attention of investors seeking to capitalise upon this unique urbanity.

Tragically, the political regime has discarded its role of comprehensive land-use planning and busied itself inventing schemes to enable what has become known as the Great Goa Land Grab (Nielsen, Pulridge-Bedi & Da Silva 2022). This has not gone unchallenged; various civil society groups and individuals have mobilised to resist the designs to damage Goa’s urban-rural system.

Composite of grey, green, and blue

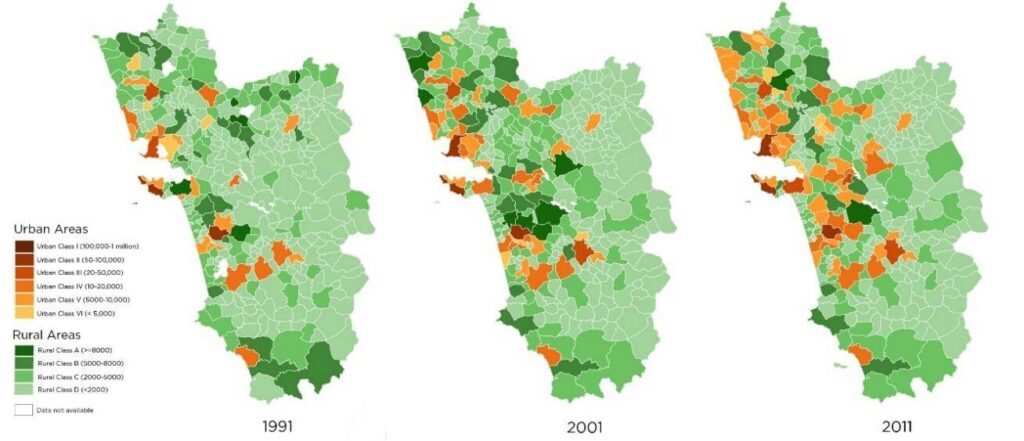

Goa’s settlement pattern is the outcome of naturally unfolding urbanisation that resulted in one of India’s most urbanised states. When studying the spatial distribution of urban areas from 1991 to 2011, Jayesh Swami and I found that what began as dispersed poly-centred urban areas have rapidly become connected into an urban system primarily concentrated along the coastline (see the figure below).

Fig 1: Goa’s urban pattern from 1991 to 2011

The notion of Goa representing a unique urban system ‘in which villages and towns intersperse with wild as well as managed landscapes, all growing into an economic and physical whole’ was proposed by urbanists Rahul Srivastava and Mathias Echanove who also speculated ‘Can Goa show the way for the rest of the country in a transformation from a rural to an urban economy, thereby offering a convincing urban alternative to the mega-cities?’.[2] Subsequently, along with Palmer and Low, I analysed the experience of urbanisation and land struggles in Goa using the trope of networks as a changing dynamic. We revealed configurations that are problematic and those that are enabling in order to promote sustainable and just urbanisation.

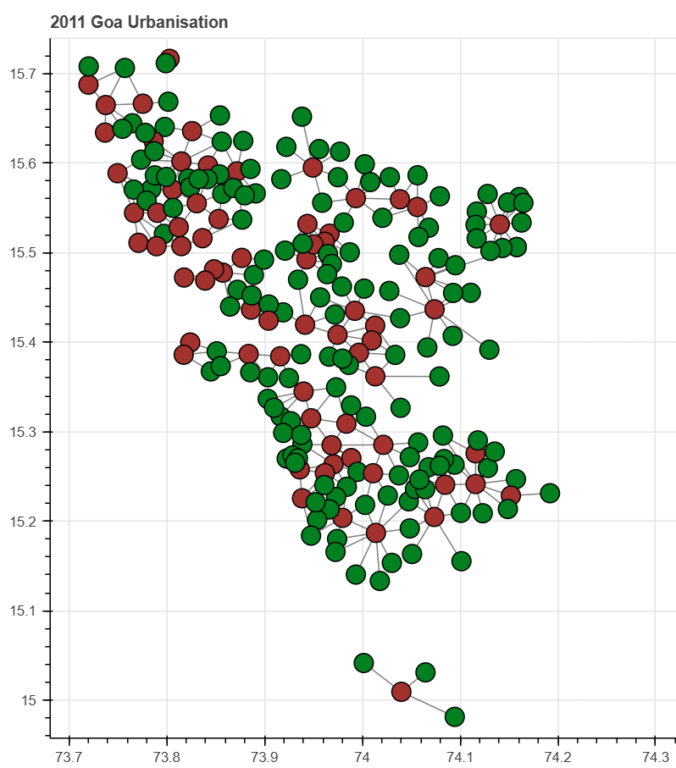

Two other studies similarly attempted to examine the uniqueness of Goa’s urbanity. One has used network analysis to demonstrate the nearness of urban spaces to rural spaces in the state (Gokhale 2021). See Fig 2. The other is a study by Swami and I, examining the extent of urban green spaces using zoning data which offers empirical support for the proposition that there are substantial green spaces in Goa’s urban system. This blending of grey and green spaces alongside fairly good urban amenities offers inhabitants in Goa a high quality of life and, as will be argued, is the product of regional and urban planning.

Fig 2: Proximity of Urban-Rural Spaces in Goa (2011)

Unique urbanity is the outcome of progressive land policies

Goa began using land zoning in the 1980s to ‘broadly demarcate areas for different land uses: agriculture, forestry, industry, urban and rural settlements’ and ‘provide areas for recreation, natural resources, gardens and sites of historical and archaeological value’ as in the Goa Town and Country Planning Act, 1974. There were institutional systems that facilitated it and these included the Goa Town and Country Planning Department (TCP) set up in 1964 and the Goa, Daman and Diu Town and Country Planning Act and Rules (GTCP Act 1974) promulgated in 1974. The Act empowered the TCP to prepare spatial plans to guide future land uses in the state.

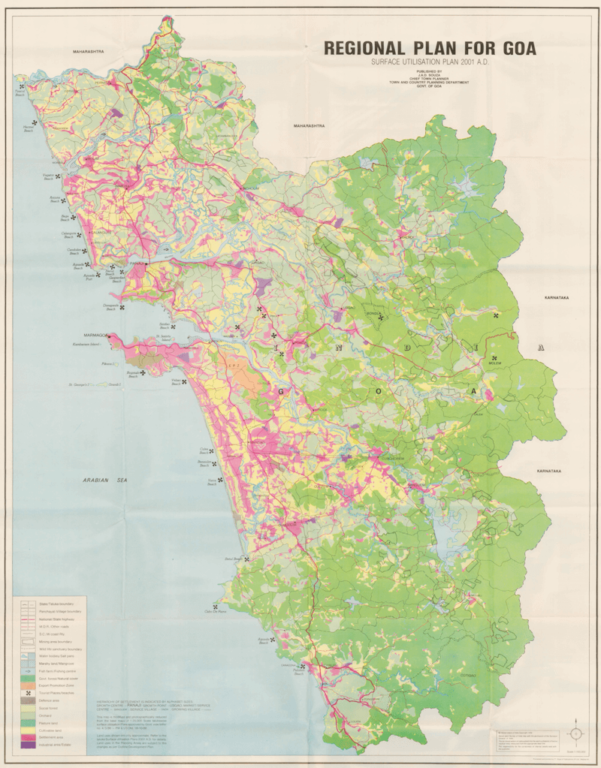

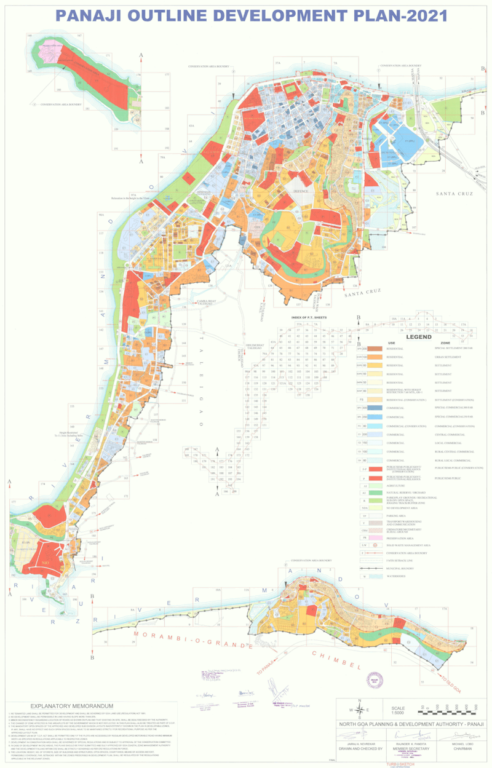

Beginning in the 1980s, the TCP created a master surface utilisation plan called the Regional Plan (RP) alongside detailed spatial plans known as the Outline Development Plans (ODPs) (see Fig. 3). The ODPs were used to regulate land uses in the state’s fast-growing urban areas. All development activities had to conform to the provisions of the spatial plans. The implication for land developers was that development permissions needed to obtain clearances – No Objection Certificates – from the TCP department, which would verify if the proposed development conformed to or violated the land use specified in the notified spatial plan.

Figure 3: Examples of Spatial Plans in Goa

Source: Goa Regional Plan – 2001 AD

Source: Goa TCP Dept.

Thus, as early as 1986, Goa had put in place legally binding zoning plans encompassing the entire state’s land mass. At the time, no other Indian state had a zoning plan that extended the entire state’s land surface. This planning intervention ensured that Goa’s agricultural lands, ecological systems, and historic sites had some protective cover from the land market that was expanding and rising in value. It is one of the main reasons for Goa’s attractive urban spaces; ensuring their proximity to green spaces and fostering an urbanity that configures the built environment within agricultural and natural green spaces.

This has arguably ensured that those who live in Goa have a sense of place where the urban or the built-up is constituted alongside agricultural and wild spaces. This unique urbanity is one of the reasons Goa has earned the title of being a lifestyle destination, resulting further in a voracious demand for opening land for speculative real estate and tourism projects. Disturbingly, however, the previously progressive land-use regulations that had set limits on land markets are now being undone by a regime that doles out exemptions from land regulation for select parties. The following will demonstrate the piecemeal way spatial plans are being undone in Goa.

The undoing of Goa’s spatial plans

The most controversial way that state governments are undoing the gains of land-use planning is by making ad hoc and case-by-case zoning changes to the existing regional plans and ODPs (Da Silva, Nielsen and Plumridge-Bedi 2020). Here, a relaxation is granted for a private party, exempting them from adhering to the existing zoning regulations that are in force for their land parcel. For example, if the land parcel is zoned as natural cover or agriculture according to the RP/ODP, the owner can apply to change the same to settlement or commercial.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This was first carried out from 1988 to 2005. The enormous discretionary powers granted to the TCP department earned it the title of being a lucrative portfolio. The practice was brought to an end in 2005 when Goa came under Governor’s rule. Jayshree Raghuraman, the then Secretary of Town & Country Planning, noted that it resulted in “haphazard development and mushrooming of concrete structures with scant regard to planning and land use norms”. She also observed that “conscious effort needs to be made to curb this practice of allowing ad-hoc changes” (file noting on 28 March 2005).

However, recently, the practice has been revived with a vengeance. It began in 2017 when the Legislative Assembly amended the GTCP Act to introduce Section 16B, which allowed private landowners to apply for case-by-case zone changes. An analysis of zoning changes processed under Section 16B from January 2019 to December 2020 indicates that over 23,16,000 square metres were sought to be converted. An overwhelming majority of the changes proposed converting agricultural land and 90 percent of all the changes sought to be diverted for real estate development.

In 2023, the GTCP Act was amended again to introduce a separate clause, Section 17(2) which enabled private property owners to request changes of zoning, this time by alleging that these were “errors” in the main spatial plan (RP-2021). From April 2023, more than 23,45,000 square metres have been sought to be converted. An overwhelming proportion has sought the conversion of ecozones to settlement.

The beneficiaries include local politicians (Chadha & Mishra 2024). In a grim analysis, over 30 percent of the changes under Section 17(2) have sought to convert Non-Development Slopes to settlements. Earlier this year, Section 39A was inserted into the GTCP Act, again allowing spot zoning by overriding the existing zoning stipulations in the Regional Plan and the Outline Development Plans (Noronha 2023). From June 2024 onwards, over 4,42,000 square metres have been sought to be converted by re-zoning agriculture and natural cover into settlements.

In a similar vein, in 2008, the Outline Development Plans which were detailed spatial plans for many of Goa’s towns were arbitrarily removed from adhering to the zoning regulations dictated by the overarching regional plan. By de-linking these plans from master planning, they were opened to manipulation via spot zoning changes. Many such piece-meal changes were made when finalising draft versions of the plan (Da Silva & Chandrashekar, 2018) or by not depicting restrictive zones such as ‘steep slopes, low-lying paddy fields, and forest areas’, despite these being marked in the RP (TCP Report 2022).

In addition to the above, the Goa Investment Promotion Act (IPB) has also permitted zoning changes. In 2014, this provision exempted commercial enterprises – cleared through this Board itself – from conforming to the land-use plans. An estimated 17,77,000 square metres have been converted using this provision (Da Silva and Noronha, forthcoming).

From the above, it is evident that the state government has used these amendments to convert significant tracts of ecologically sensitive areas for real estate and tourism purposes. The rapid transformation of land in Goa has come at odds with the sense of place held by many of its inhabitants, which has prompted Goa’s own land wars.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

How is this being contested?

While the politician-builder nexus argues for the need to open up land for housing and ‘development’, 22 percent of houses are unoccupied in Goa[3] and the state has become India’s capital for second homes. However, Goans have been acclimatised to an alternative urbanity with an intimate scale and have closely networked with rural spaces. The urban spaces are enmeshed with agricultural and green spaces; this is the urban imagination of Goa’s residents.

The state has also had a long history of environmental struggles, such as the Ramponkar movement in the mid-1970s, the agitation against the Thapar-Dupont Nylon 66 project in 1995, the Konkan Railway agitation in the early 1990s, the Goa Bachao Abhiyan movement in 2006, the anti-SEZ movement in 2007 and the legal challenge that resulted in stopping iron ore mining in 2012. It is, therefore, unsurprising that the scale and pace of land use changes resulting from the manipulation of zoning laws have been met with resistance.[4]

This has taken the form of protests led by village groups and civil society actors and, in numerous cases, has been supplemented by court cases filed in the High Court. At the time of writing, Section 16B, 17(2) and 39A – all provisions attempting to spot zone various parts of the state – have been challenged in the courts. Several Outline Development Plans have also been successfully challenged. In most of these challenges, the status quo on land conversion has been maintained pending the disposal of the cases.

Reflections

The land-use planning experience in Goa clearly shows, on the one hand, the capacity of politics and governments to influence progressive urban planning, which created livable urban systems of cities and towns alongside the rural and the ecological, and which gives Goa its unique character. However, on the other hand, political power demonstrated in amendments to land-zoning laws and manipulation of the zoning system erodes the promise of Goa’s unique alternative urbanity by allowing the creation of land banks for tourism and real estate projects. Goa’s civil society, from its long tradition of resistance, is playing an important role in exposing and resisting the state’s problematic design and holds out the hope that the state’s land laws will continue to protect its ecological and historical sites.

References:

- Chadha, Pavneet Singh & Mishra, Dheeraj (2024) ‘2 Goa Ministers, local BJP, Cong leaders – look who benefits from tweak in state land use law that threatens ‘green zones” Indian Express, 09 Sep 2024, pp. 1 & 9.

- Da Silva, Solano & Noronha, Tahir Fernando (forthcoming), Land-use Planning in Goa: One hand gives, another takes in Fish Curry and Rice: A Source Book on Goa, Its Ecology, and Life Style [In Press].

- Da Silva, Solano and Chandrashekar, Ananth 2018, ‘73 & 74 Amendment has been Kicked out of today’s ODPs’, Herald Forthnight, pp. 9–11.

- Da Silva, Solano; Kenneth Bo Nielsen & Heather P. Bedi, 2020, Land use planning, dispossession and contestation in Goa, India, in Journal of Peasant Studies. pp. 1301-1326.

- Gokhale, Chinmay (2021) Exploring Rural-Urban Networks in Goa, Study Oriented Project at BITS-Pilani K K Birla Goa Campus, under the guidance of Dr Solano Da Silva, Dept of Humanities & Social Sciences.

- Govt. of Goa, ‘Report of the Expert Committee on Outline Development Plan for Calangute-Candolim Planning area-2025, Outline Development Plan for Arpora-Nagoa-Parra Planning area 2030 and Outline Development Plan- 2030 for Vasco-da-Gama Planning area.’ 4 July 2022

- Nielsen, Kenneth Bo; Plumridge-Bedi, Heather & Da Silva, Solano 2022, The Great Goa Land Grab, Saligao: Goa 1556.

- Noronha, Tahir 4 June 2023, ‘The Economics of Arbitrary Amendments’ [Editorial] Herald

- Palmer, Henrietta, Da Silva, Solano & Low, Iain (2021) ‘Networks: Struggles for Land Justice and Belonging in Goa, India’ in Palmer, H. (2021) The Language of the Becoming City, Berlin: Jovis, pp. 126-161.

Solano Da Silva is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Humanities & Social Sciences at BITS-Pilani KK Birla Goa Campus. He primarily teaches Development Studies and Political Theory. His research has looked at electoral politics, urbanisation and land-use planning with a special focus on Goa. He recently co-authored a book titled ‘The Great Goa Land Grab’.

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons