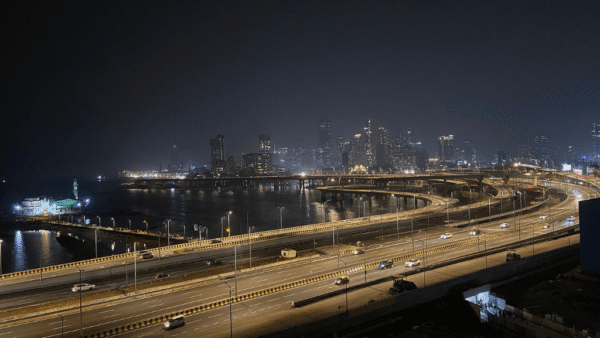

Off the Eastern Freeway, on the eastern side of Mumbai, is an array of decrepit brown buildings stacked dangerously close to each other with poor ventilation inside homes and absent green spaces outside. This is, obviously, a slum resettlement colony, one of the hundreds in the city. In between the buildings are dark and smelly alleyways, litter strewn here and there. Inside the buildings, corridors are stacked with household goods. Here, in Natwar Parekh Compound in Govandi, as in other resettlement colonies, no one seems to have given a thought to the needs of children.

The children, though, found ways out of the dinginess. They figured, with some nudging and help by civil society organisations and volunteers, that they could bring colour to their spaces, in fact even create spaces for play and care. Safe spaces, exciting spaces, spaces that any child would relate to. Gradually, three years ago, Kitab Mahal, the library, came to be and marked the first edition of the Govandi Arts Festival. Then came along Humraahi (companion), a space for children to study, play and express themselves, and Awaaz (voice), a space for the children and women to relax and bond. Together, the children-created spaces are evocatively called Ek Aasmaan Tale (Under One Sky).

These are colourful and vibrant spaces. Importantly, they meet the community’s needs for play, care, safety and companionship that the planners and builders had not drawn into plans. While Kitab Mahal is primarily used for reading and learning, Humraahi is where hundreds of the nearly 3,000 children in the neighbourhood come to feel, release and reflect on their emotions through art every week, and Awaaz is where women and children come together for a break from their punishing routines. “We have found friendships here, away from judgement and watchful eyes. It is a safe space,” says Shireen Ansari, 27, a homemaker.

In creating Ek Aasmaan Tale and using the spaces in their daily lives, what the children and women of Natwar Parekh Compound have shown is the abject lack of such spaces in mainstream planning and the growing realisation that such spaces have an impact on children’s lives. If the template of Ek Aasmaan Tale can be adapted and applied in other lower-class or impoverished neighbourhoods, where dedicated spaces for children are not mandated by policy, it would help to fill a yawning gap in how our cities are planned and made – without considering children at all.

Photo: Nikeita Saraf

Why Natwar Parekh Compound matters

Govandi is an undesired address in Mumbai. It immediately slots the resident as impoverished and, therefore, lacking in attributes needed to pass the smell-look-language test in the city. Children with a Govandi address have been denied admission in colleges outside the neighbourhood. Most, not all, families here are Muslim. Govandi is a part of the M-East civic ward in Mumbai, the poorest area under-serviced or unserviced by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation.

Back in 2009, when the BMC brought out the Human Development Index report, it ranked M-East ward, in which Govandi falls, the lowest among Mumbai’s 24 wards. The life expectancy of the ward was 39 years compared to the average urban life expectancy in Maharashtra which was 73.5 years.[1] and the open space per capita was only half a square metre.[2] The Deonar landfill, open and polluted, and a bio-waste treatment plant are major health risks here.[3] The M-East ward also has a large number of factories and slums. Low literacy rates, especially among women, and a high incidence of people exposed to climate-related risks such as heat stress underscore the lack of recreation spaces.

The Vulnerability Assessment for Mumbai found that the ward ranks low on access to the most basic amenities.[4] The deplorable state led to the Maharashtra State Human Rights Commission, in 2023, to direct the state government and the BMC to improve public infrastructure and existing civic amenities.[5]

Natwar Parekh Compound’s residents are construction workers, cab drivers, delivery drivers, and service providers whose informal work helps run Mumbai. As the city was selectively redeveloped and new infrastructure erected, many of the displaced were given houses here and they joined poor migrants who could only afford rooms here. The buildings – almost nestled, too close for comfort or air, poorly maintained, dark and filled with stench – give this away. Any space around or in between the buildings, has heaps of garbage or two-wheelers parked.

Children are forced to play away from the buildings which, despite being in the colony, offer little safety. Older children have been caught with alcohol and substances, violence has broken out. Even if boys were allowed to play here, girls were not. Women had no place to leave their young children and head off someplace. There were no spaces for them to come together and just talk.

The transformation

The spaces that Ek Asmaan Tale created have made a world of difference. The three spaces are tucked away on ground floors of three buildings, in rooms earmarked as offices of the buildings. They have a common language of free-flowing floor area, walls flanked by furniture and seating spaces, and small elements that give character. The layout in each can be changed as per needs. A pantry and a toilet are common amenities to all the spaces.

Awaaz is situated in building 6B in the centre of the colony. On most days, at 3pm, women come here to drop their children off or head to Humraahi to leave them there. They get some coffee going, filling the room with the aroma. Soon, cups are passed around on a large steel plate. They say they are happy that someone thought of creating this space. It’s important because they know their children will be safe here and occupied with play. They no longer lock the children at home.

Safiya Khan, 40, says, “Idhar sukoon ka jagah hai (There is a quiet/peaceful space). Many formed friendships here. “Yahan pe aake lagta hai na baccha hai na aadmi hai (I come here and forget that I have a husband and child),” jokes Zulekha. This is also where women get some rest after gruelling days or household chores. Soon, there will be Spoken English classes for them here, on their request. Film screenings have been organised here, women recount lying down to watch films. Sayeeda Sheikh says, “We have a TV at home but I had never watched a complete film.”

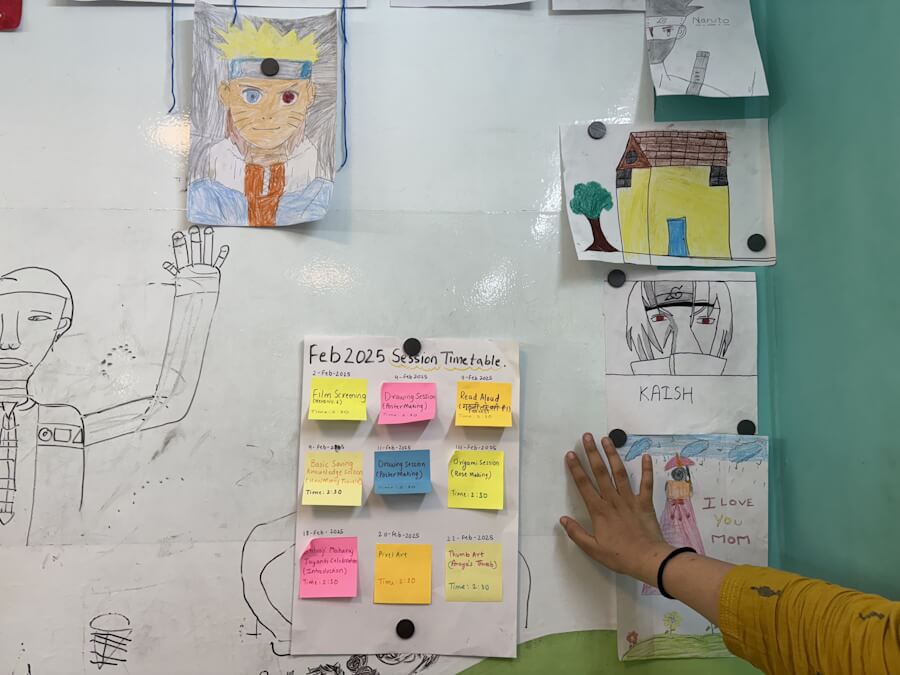

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Humraahi is designed as a space for children to study, play, and let their expressions flow. They run between walls, label their emotions on the emotions board, draw on a wall with an erasable film, climb on a small ladder, and more. Little niches, soft edges, cushions, and rearrangeable furniture blocks all invite them to have fun. This place has its roots in the anxieties of mothers who were shaken when a 15-year-old murdered someone and they found anger festering in children. The feelings-wall was designed for children to use different coloured bangles to express themselves. Saba, 19, a student who works part-time at Humraahi, says, “Children come here to simply run around or invent their own games and play.”

Tayyaba, 23, a graduate in Management Studies, and Sana Sheikh, 21, a Commerce graduate, have been working with Kitab Mahal since its inception. They started off as part-timers but now manage the space full time. It took them two years to build trust. “There had to be detailed conversations with parents about the children’s safety,” says Tayyaba. Sakina, 17, who conducts arts sessions, is thrilled to be here because she also gets free supplies.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

How the transformation happened

The spaces are integrated into the community despite being so starkly different from what people were used to. People see themselves in a new light too. Children demand workshops; there have been book readings, drawing and mehendi sessions, sound therapy, music, drama, poetry, Mandala colouring, writing and reflection sessions, and film screenings.

“Creativity is the best kind of expression to have and that’s the first thing that gets cut off when children are told ‘don’t do this, don’t do that.’ Here, we want them to be free, draw on walls all they want,” explains Natasha Sharma, Lead, Public Arts and Design at Community Design Agency (CDA) which carried out various interventions in Natwar Parekh Compound over the last seven years, including the Govandi Arts Festival. A child, prancing to fill water bottles, flashes a heart sign with hands at Sharma; she smiles back. This connection is precious to both.

In the by-lanes, a group of teenagers are being trained to shoot photos as a part of the mentoring they are getting for the second edition of Govandi Arts Festival this November. They go back to Kitab Mahal to discuss their work with the mentor where brightly painted walls and bookshelves stacked with an array of titles await them. Sana says, “People from outside the colony also come here to study after looking up on Google. It’s a common assumption that it’s a paid-for space because of the way it looks.”

Eight facilitators from the community work here in shifts to plan the programmes and keep a record of children’s attendance. The young women’s presence has encouraged other young women to step out of their homes and come to these spaces. But it was not so easy, always.

Ek Asmaan Tale had to be convincingly sold as an idea to residents before it was taken to civic officials for permissions. The need for leisure–play spaces, where residents struggle for basic amenities, was frowned upon. Children did not matter. The chairperson of the housing society and self-styled important men had to be on board to rent out the rooms. They declined to part with the rooms. A tailor shop, to be set up there, would fetch higher rent.

Parveen Sheikh, a resident and community organiser, stepped in to play a key role in swinging the decision. Then the women got together and expressed their ideas. The next hurdle was the Social Cell of the Mumbai Metropolitan Development Authority (MMRDA). Once the society men bought into the idea, they pursued the officials and did the paperwork. All along, the CDA supported them, holding meetings, explaining design and art, and so on.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Periodic transfer of officials meant delays. Kitaab Mahal got support from the MMRDA while Humraahi and Awaaz needed funds. While the allocation of rooms and a No Objection Certificate was MMRDA’s contribution, the programmes are sustained by residents and the CDA, Sharma says. The visible impact has meant the authorities are now encouraging the residents and the CDA to similarly transform other unoccupied spaces too.

“Spaces of rest, leisure and play should not be inherited or available based on your bank balance,” says Sharma. She questions why, despite having livelihood and access to basic formal education, children and adults do not feel a sense of belonging to a place. “We did not know we could go out on our own, go out to work. Now, we do as we wish,” says Tayyaba. They understand their right to the city, to space. “At a workshop on cities for children, our Govandi kids said they have everything they need in their colony,” she adds.

Economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods have fewer public spaces for everyone, especially children, opines Zahra Gabuji, a storytelling and arts education practitioner. “Community libraries help children build skills and expand their thinking. These are places where children learn beyond the binaries,” she says.

The empowerment and agency that the children, and women, feel here can pave the way for how similar spaces are imagined in other areas. “When our role here reduces, it’ll be our success,” says Sharma. The planning paradigm does not account for leisure spaces for the under-privileged. Natwar Parekh Compound’s residents, especially children, show this can be changed. Sharma says, “What we did in a community of 25,000 residents here demonstrates what can be done in the city at large. Open spaces, parks, community centres that are well-maintained, where you can collaborate with people should be in the city’s plans and budget.”

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Reporting inputs by Nikeita Saraf

Cover photo: Humraahi is an emotions-led activity and play space for children. Credit: Jashvitha Dhagey