If the verdant dense forest of Mumbai’s Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP) could speak, it might have railed against the draft zonal master plan rolled out last month to allow construction and ‘development’ in its eco-sensitive zone. Elected governments and authorities are its custodians. When these custodians disregard its ecological value and treat it merely as land to be monetised, they sign its warrant for a slow end. The plan for the eco-sensitive zone is its death warrant; there’s no gentler way of saying it.

If the authorities, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation under apparent directions of the Maharashtra government, have their way with the plan, not only the eco-sensitive zone but the entire 106 square kilometres of the SGNP will be under threat. The zone is almost 48 percent of the total park area. The plan classifies the eco-sensitive zone into three categories and allows construction in two of them, terming them as developable land.[1]

But the forest does not decide its eco-sensitive zone; people in power do. The mapping of the zone, done after due deliberations years ago, was to consolidate it as a buffer between the SGNP forest and the chaotic, polluting, ecologically disruptive activities of Mumbai and Thane cities that abut it. It was protective armour for the forest. The master plan proposes tearing down this armour in the name of development and infrastructure. This has resonance beyond Mumbai; across India’s cities, governments are making plans to usurp forests and tree covers for construction.

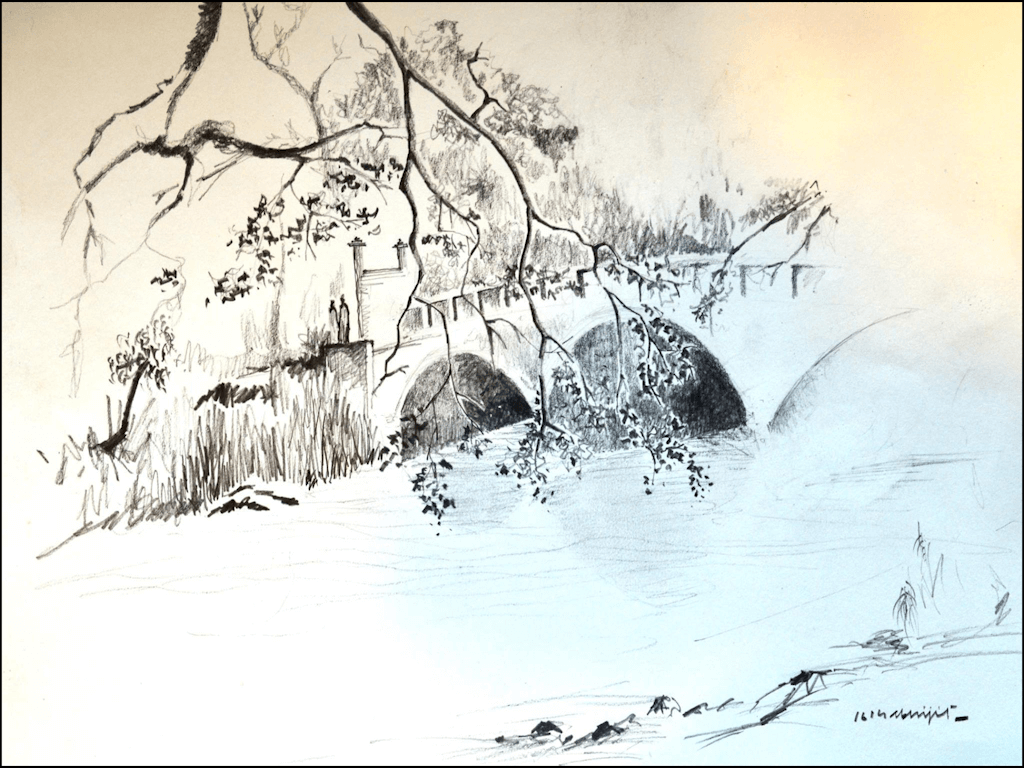

The illustrations, including the one above of a bridge over the Dahisar River, by urban planner, geospatial analyst and teacher Abhijit Ekbote bring out the varied riches of the SGNP. The tourist footfall ranges from 1.3 to 2 million a year but this is in the open area.[2]

The BMC admits, in the plan, that nearly 34 percent of the eco-sensitive zone has been already encroached upon by slums, industrial activity, commercial use, and transportation but presents 66 percent as ‘developable’ land. This is a shocking admission and interpretation. It failed to prevent structures other than old tribal settlements here. They should be demolished and the ecology restored; instead, the BMC interprets it as correct and proposes more construction.

Often called Borivali National Park after the Mumbai suburb, the SGNP is a contiguous spread that extends to the Aarey forest to its south.[3] The Aarey falls in the eco-sensitive zone but has been gradually opened for ‘development’ including the construction of the controversial car shed of Metro 3 line.[4] Now, the BMC plan opens up more of the eco-sensitive zone. How long before the forest itself is considered developable land?

The plan may well be the final straw that shrinks and strips the forest. It must be withdrawn – in the interest of both the forest and the cities. As it stands, it threatens the ecological security of Mumbai and Thane which together are home to nearly 20 million, disrupts the web of life that the SGNP supports in the dense cities, jeopardises climate action plans as temperatures rise and rainfall intensifies in these cities, and it violates 30-year-old court orders to protect the eco-sensitive zone and the forest.

The BMC sought objections or suggestions to the plan till October 17. It received thousands; just one of the petitions carried 26,100 signatures and protesters sent some 8,000 emails.[5] The prudent, ecologically-sound decision would be for the BMC and the Devendra Fadnavis-led government to withdraw the plan. If there must be a plan, it should be to protect all of the forest including the eco-sensitive zone and human-made boundaries, with the participation of the Adivasis who have lived there for ages.

The web of life

The SGNP, both the core forest and eco-sensitive zone, is not an independent territorial space in Mumbai-Thane but the plan, typical of such documents, asks us to see it in a fragmented way, separate from the ecology of the cities. Fragmentation is a myth. The forest, at the northern edge of Mumbai and to the west of Thane, is deeply connected to the ecology of both the bustling cities and forms their web of life, an integral part of their geography.

Its ecology – the mountains, the forests, the rivers, the water courses, the floodplains, the vegetation, the birds and butterflies, the life below soil and groundwater – all constitute the ecology of the cities. The forest and cities are inter-connected, inter-dependent, and must be seen as such. Ecological security of Mumbai and Thane naturally demands that the forest is protected in whole, including its eco-sensitive zone.

Besides Mumbai and Thane, in Palghar and the newly densifying suburbs of Mira-Bhayander that the SGNP touches, its green has been the carbon sink making air less polluted and cooling temperatures, its rivers have fed their water bodies,[6] and it has offered millions of people the only slice of nature they can afford. The SGNP is also home to thousands of Adivasis, primarily the Warli tribals, it carries archaeological significance with its caves dating back to the Buddhist era, and is a biodiversity hotspot with rich wildlife.

Without it, Mumbai-Thane would be hotter and more polluted, water supply would be affected, and the cities would lose their oldest and densest natural green. Instead of protecting this web of urban life, the BMC proposes to squander it away for a few roads here and tourist resorts there. Where is the Forest Department in this planned stripping down of ecological wealth?

This is a classic fragment-and-present approach – propose construction in a section of the forest, show it is in public interest, and point to other parts protected. The plan wants people to not see the inter-connected web, the whole picture. Those who see through this fragmentation are bound to oppose the plan. The approach was seen in Aarey too. A part of the same forest, it falls in the eco-sensitive zone, and should have been protected. Instead, after protracted struggles, 812 acres of its 3,162 acres were tagged as forest by the Uddhav Thackeray-led government in 2020 but other areas were gradually opened for projects after the Metro 3 car shed was constructed.[7]

The template of fragmenting the contiguous natural green expanse – between Aarey and the SGNP or within the latter – suits the mega land use plans of the Fadnavis-led government. Seen with the usurping of 256 acres of Mumbai’s salt pan lands for the Dharavi Redevelopment Project, the city’s natural web of life is under severe threat.

The contradictions, why they matter

The BMC’s plan has strange contradictions. First, by brazenly classifying the eco-sensitive zone into three categories – ESZ1 closest to the cities – and proposing infrastructure projects, eco-tourism, and construction in ESZ1 and ESZ2, it suggests that all of the eco-sensitive zone does not need to be protected although the forest does. But the eco-sensitive zone is, indeed, a part of the forest itself.

Secondly, the plan negates the pitched battles of the 1990s to protect the eco-sensitive zone. Thousands of slum settlements there were evicted on the orders of the Bombay High Court after Mumbai’s environmentalists, especially the Bombay Environmental Action Group, had approached it to demand their eviction[8] to protect the SGNP. Social activists and housing rights organisations like the Nivara Hakk Suraksha Samiti had argued that while the protection of the forest was indeed important, the slum dwellers had to be rehabilitated before eviction. The judgment, with more than 300 interventions, came in 2003 and was clear that there can be no parting of forest land for any purpose.[9]

It is important to note that the encroachments were not in the core forest but in the buffer or eco-sensitive zone. Protecting this zone was considered critical then; now, three decades later, the BMC officially proposes massive construction in it including eco-tourism facilities, businesses, housing units to rehabilitate Adivasis and eligible encroachers, infrastructure projects like drainage and transport systems. What changed in the intervening decades that the eco-sensitive area can now be officially built upon? Is this not contempt of court? The Janhit Manch, a NGO, has approached the HC alleging this but others are yet to speak up.

If construction in the buffer zone could be permitted, why did the slum dwellers and Nivara Hakk have to fight hard then to ensure that, of the 50,000 tenements, at least the 25,000 deemed eligible should be rehabilitated? It was a protracted struggle, captured in the report Crushed home, Lost Lives.[10] Subsequently, with the HC’s acceptance, the rights group has provided alternative accommodation to about 15,000 so far. On the Thane side, the constructions include lavish bungalows to which authorities mostly turned a blind eye. In the ethnographic research on the subject, IIT-Bombay researchers concluded that this “indicates the extent to which conservation politics in a city like Mumbai have diverse consequences for Adivasis and slum dwellers residing within the park, representing an elitist environmentalism neglecting poverty alleviation, social equity and human rights.”[11]

Adivasis have been living in SGNP for generations and are protectors of the forest.The class contradiction is all too apparent. Slums were not welcome but eco-tourism and other constructions are. Research like this[12] explored how “the relationships between the poor and the environment are framed on the conservative premises that poor encroachers were mostly responsible for the degradation of the park… New and apparently legitimate forms of urban governance, in our case the judiciary, maintain social prejudices and contribute to displace the poor to the periphery.” This October, the Bombay HC while setting up a high-powered panel to oversee the rehabilitation of encroachers and the restoration of the SGNP,[13] remarked that slum dwellers “can’t say you have a right to remain there forever.” Presumably, planned projects have the right.

Another contradiction lays bare two Mumbais. In the past few months, furious efforts were made by a section of the elite in south Mumbai to turn 100 acres of barren land along the coastal road, having no soil cover, into a lush coastal forest. From aggressive social media campaigns to meetings with the BMC, the movers and shakers put corporate might behind creating the coastal forest;[14] they have been relatively silent about protecting the existing natural SGNP. Also, on the one hand, the BMC indulges their forest creation while, on the other, prepares a plan to destroy the eco-sensitive area of the existing forest.

The historical context is important

Recognising the contradictions and recalling court orders is important for the much-needed historical context to the current battle to save the SGNP and its eco-sensitive zone. The current resistance is a continuum of many struggles over the decades. Earlier, the focus was to stop quarrying activities in the forest area, shut down a meat factory, and evict slum dwellers; now it is to resist officially legitimised construction. The battle itself is old and same – to protect the forest.

Previous battles had turned ugly too. In the slum dwellers case, the HC even directed that Nivara Hakk activists not be seen within four kilometres of the SGNP boundary and ordered inquiries into their antecedents; many were beaten up and jailed, there was helicopter surveillance and army deployment.[15] The historical context includes an observation. When Nivara Hakk activists ventured into the buffer zone to provide relief to the slum dwellers, many of whom belonged to minority communities, during the 1992-93 communal riots in Bombay, they noted that the slum settlements were not random but an organised ‘town planning scheme’ which pointed to a nexus between forest officials and the police.

Over the years, Adivasis too have taken up cudgels inside the forest and buffer zone to protect their lives and livelihoods disrupted by plans and projects.[16] The draft zonal master plan represents the latest massive challenge, even relocating them, some of the forest’s oldest residents. On the Thane side, a radar installation was stopped by environmentalists but the posh bungalows in the Yeoor hills were built anyway; the Yeoor area even has artificial turf and a casting yard[17] and these projects, environmentalists say, have already impacted the natural corridors hindering wildlife movement.

The ‘Save Aarey’ movement saw thousands of people joining forces to resist the Metro 3 car shed, fighting hard through nights to save 2,400 trees from being hacked – all in vain. In fact, Mumbai’s Development Plan 2034 projects Aarey as an urbanisable zone. The draft zonal master plan, then, is a part of this grand plot to open up more and more areas for construction. Environmentalists, social activists, planners, hikers and students are resisting on the ground and exploring legal avenues to push back.

However, it’s an infuriating irony that people with little time and resources must rise to protect the SGNP including its eco-sensitive zone while its custodians – the BMC, Thane Municipal Corporation, and the state government – make plans to destroy it.

All illustrations by Abhijit Ekbote