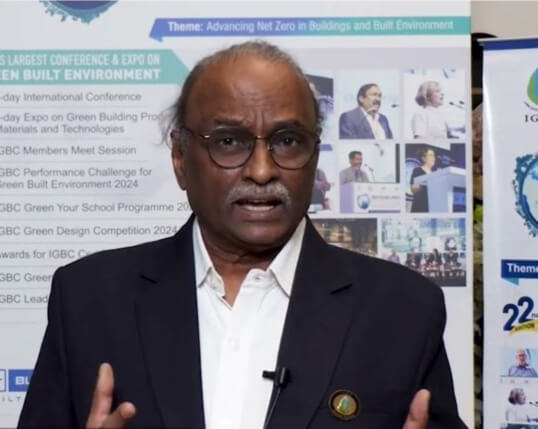

From its early fairytale-like start, over 20-plus years, the awareness and the need for green buildings or net-zero buildings has spread. However, senior architects who call the shots remain unaware and engineers, who matter more to design by making buildings power and water efficient, have to embrace the concept; equally important is the demand from buyers and renters which can persuade the market to make certified green buildings the default, says Dr Hariharan Chandrashekar.

An ecological economist, academician, and industry advisor on sustainability issues, Dr Chandrashekar has been a mentor to enterprises and entrepreneurs on, among other aspects, green buildings. A founder-member of CII’s India Green Business Council National Executive Committee, he is also the chairperson of the agency’s Bengaluru Chapter. In this interview with Question of Cities, the path-breaker recalls the early years and likens his continuing naivete and hope for green buildings to the legendary Don Quixote and the Windmills.

Can you talk to us about the initial days of the green building movement in India?

In 1991, India embraced liberalisation and, through it, economic independence. The abuse of the environment was evident but, in retrospect, it was nowhere as dangerous as it is today. Indian cities were still manageable; we had not seen the frenzy of construction yet. The first stirrings of the idea to make buildings energy efficient was in 1998. It would not be a travesty of the truth to say that the green building movement started that day in 2001 when some of us took a collective decision to house India’s premier Green Business Centre in a green building in Hyderabad. That was a “leap of faith” decision.

In mid-January 2000, to prepare for the then US President Bill Clinton’s India visit next year, Padu Padmanabhan got a call. He had moved from the World Bank to USAID for a two-year stint in New Delhi. The call was from V Raghuraman, energy advisor to the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), to ask if Padmanabhan could strengthen the case for President Clinton to visit Hyderabad. A joint endeavour of a Green Business Centre might be of interest to the White House given that climate change was high on President Clinton’s priorities. One bureaucrat triggered the idea of what became a movement.

During President Clinton’s visit, chief minister Chandrababu Naidu offered five acres of land to the CII to create the India Green Building Council (IGBC), India’s first green building. The design for its headquarters was born in Washington DC when architect Karan Grover sat overnight in Hotel Waterloo and drew up a schemata to present to Kath Williams and others of the US Green Building Council the next morning. Today, the 20,000 square feet building stands in the Hitec City of Hyderabad.

What were the early years like?

After the IGBC was formally launched in 2004, the next six years saw no more than one million square feet come up for certification. There was not much understanding of what green buildings meant. In the first five-seven years, only a few builders sought certification. The company I led, Biodiversity Conservation India Ltd (BCIL), had created the first sustainable residential enclave called Trans Indus in Bangalore in 1995-1999. After 11 years and four such projects, we hosted the second Green Building Congress with support from another builder in Bangalore and inputs from leaders from Indian Society of Heating Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Engineers (ISHRAE) which included Dr Prem Jain.

I continued to build but suffered a market that was very slow to accept the idea. Many walked away; they wanted a ‘builder’, not some ‘eco innovation freak’ as one prospective purchaser told me. Sales were a challenge for the focus was on sustainability, not location. I lost the market edge. Later, green certification was available with Green Rating for Integrated Habitat Assessment (GRIHA) and US Green Building Council (USGBC) apart from IGBC. By 2010, thanks to some professionals, a few larger buildings came into the ‘green net’. The IGBC did a MoU under which commercial buildings got US-based LEED certification and LEED got visibility in India. Even if people were willing, there were two operational challenges: higher cost and evolving methodology which made compliance difficult for engineers.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

How did the construction industry respond? Was there resistance from developers, architects, and policymakers?

Between 2005 and 2014, it was not just resistance; they did not want it for they did not see a market. Further, buildings with global companies as tenants did not put ‘green’ as a precondition; that happened only around 2012. Even today, multinational companies prefer LEED, not IGBC, rating but in those days, architects were not even aware of such a concept. Policy was very slow to be adopted.

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs was not willing to recognise either GRIHA or IGBC as rating agencies until 2012-13. That year, the IGBC managed to reach one billion square feet and set a target of 10 billion square feet for 2022. Even then, builder associations like the Confederation of Real Estate Developers’ Associations of India (CREDAI) or National Real Estate Development Council (NAREDCO) did not persuade their members to adopt the rating system. Only around 2020 they began to explore this possibility.

How has the definition of a green building evolved? What key shifts have you observed in materials, design approaches, or energy efficiency benchmarks?

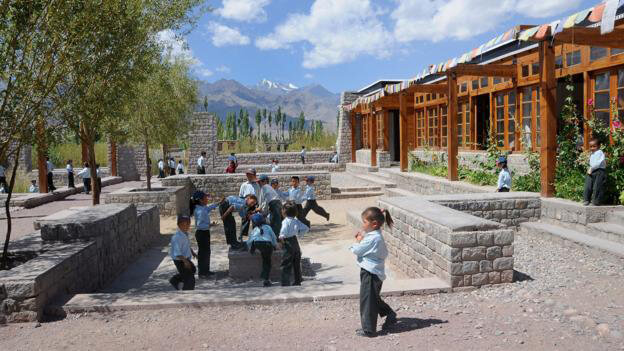

From ‘green’ being the colour in the 1990s and 2000s, it is now associated with sustainability. There are very few builders, even in Tier II and III cities, who are not aware of green buildings. Yet, the total number of certified green buildings is still under five percent of the entire building stock of over 200 billion square feet. The methodology of ratings has to become acceptable for engineers who make more difference than architects do. The key lies in enabling the process and methodology for engineers; certified architects do not impact more than 7-8 percent of all buildings constructed while civil engineers account for the major chunk of plans and sanctions.

For engineers, the challenges lie in understanding Scope 3 of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) or the nuances of Businеss Rеsponsibility and Sustainability Rеporting (BRSR). The new guidelines or the revised National Building Code 2025, now in the making, are areas of relative darkness. There have been no significant changes in materials use because engineers do not have alternatives or are not aware. Most architects trained in the 1980-90s are still focused on aesthetic, volume, and space, and have a distaste for understanding structural or water-energy efficiencies that buildings need. Engineers are trained to drain water and not to harvest it.

Have industry-led agencies like the IGBC and GRIHA been instrumental in mainstreaming green buildings or has policy played a bigger role?

The construction sector and builders are waiting for the government to enforce greater mandatory compliance. So far, most buildings have voluntarily done the certification but individual buyers or renting companies are still not demanding ‘green’ buildings. The Energy Conservation and Sustainable Building Code (ECSBC), as it’s now called, is still to be implemented. Most architects still are not aware of the nuances and demands that its provisions or ESG make on buildings.

Although India has signed the international climate protocols, the recent setback – of the US pulling out of the climate accord – will mean other signatories may go slow. The Government of India has taken the position that India is a ‘victim of climate change’. This means government mandates for compliance with green norms will slow down. However, the awareness in the marketplace could lead to a steady rise in the certifications sought. In 2024–2025 alone, the IGBC has set a target of 2 billion square feet; remember that it took ten years to reach the one billion square feet mark. So, there will be accelerated growth in green buildings. The scarcity of water will also put pressure on buildings to be water and energy efficient.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What advancements in materials, construction methods, or digital tools do you believe have had the most transformative impact on green buildings in India?

These have all been good supplementary aids for the acceleration we need. There are over 5,000 building products certified under the Green-Pro certification after evaluating the use of energy and water in manufacture but the process of evaluation has been lax in examination of carbon. The issue is that more than 80 percent of new buildings have clients who are completely unaware of the advantages of resource-efficient design. The trans-disciplinary learning is not available to senior architects who exert influence more than the rigour that new architects bring. Today, in India, we have 7,000+ IGBC Accredited Professionals (APs); the US has over 2,50,000 such LEED-certified APs for its 16 billion square feet of green buildings as against India’s 13 billion square feet. India has about 25,000 architects but nearly 10 million engineers in the construction sector alone, so it is important that they understand.

With the focus on net-zero buildings, circular economy principles, and embodied carbon, do you think India’s green building movement is keeping pace with global trends?

It is useful to remember that India is the highest in the world, for the last ten years, in terms of compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) for buildings certified, though we are second to the US for the total numbers. We are more than keeping pace with trends in Europe and Australia. The single debilitating factor for India is that there are no standards and codes in the execution process for design or construction, no certified plumbers or electricians, no independent certification needed for plumbing systems in a building. Similarly, for electrical systems.

Until we have codes and standards which are rigorously implemented with mandatory requirements from urban local bodies or government agencies which sanction plans or issue occupancy and completion certificates, the acceleration will not happen. India’s green building movement is very strong in terms of research and content, the process and methodology have been evolved over years by a fine set of professionals and industry bodies. The need is for mandates from the government; this is a major debilitating factor.

What barriers exist in making green buildings the norm? Is it cost, awareness, policy enforcement, or something else?

The major barrier for acceleration is the unwillingness of central and state governments to push for initiatives for the building industry. For example, 12 states offer additional FSI for certified green buildings; the rest including Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala have not shown the inclination or interest for such incentives. Most city administrators offer platitudes on the need for climate action but are clueless about what needs to be done. Even green consultants have fallen into a dull rhythm of audits and evaluations without looking for solutions to directly reduce carbon at operational levels.

There is no conscious effort to train professionals or city administrators in the green buildings processes. Governments are unwilling to see the obvious advantages of reduced use of energy or water. The reality is that politicians will not accept demand-side management of energy or water because lower public expenditure does not have the allure that large projects do. For example, a reduction of one million litres a day in a building can result in 6,000-tonne CO2 emission reduction and a mere 1,00,000 units of reduction in energy consumption can mean saving 80,000-tonne CO2 emissions. We do not realise that more than half a city’s energy bill is for transportation of water.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Having played a pioneering role, what advice would you give to young professionals and policymakers? What unfinished work would you like to see?

“The tragedy today is that the educated and moneyed are altogether out of touch with the vital fundamentals of our Earth and all she sustains” said Mira Behn in 1954. Schumacher spoke of how “…we have forcibly broken into Nature’s larder and are emptying it out at a breathtaking pace” also in 1954. In 1970, Alvin Toffler wrote of the alarming directions that the world would take if we did not reverse things. No one took heed; he died a broken man in 2016 in Bel Air, a suburb of Los Angeles, which had to be evacuated after the wildfires this year.

I have had my moments of despondency at the Himalayan failure that I have been in not inspiring change. The combination of people’s unwillingness to see the obvious threat coupled with human desire to acquire is a sad story of an inevitable collapse. We have seen seven civilisations disappear in less than a century after having survived two millennia – Babylonian, Egyptian, Mesopotamian, the Sumerian, Indus Valley, Mayan and Incan. The writing on the wall is loud and clear; yet, we hide under a welter of mandates, rules, guidelines. Companies who claim to be green have practices so primitive and regressive in their operations that it is appalling.

All pioneers have to bear the cross of not requiting their vision in full measure. They demonstrate possibilities but cannot expect others to emulate. In contemporary governance, the magnificent obsession with large projects and money is on a scale that’s benumbing. Customers and buyers are primarily to blame. A transformation in the marketplace can only, necessarily, be with market-led interventions. The pressure to reduce net carbon emissions will make administrators and politicians to bring in change. That is the only hope.

In the post-Covid years, I have pushed initiatives with young entrepreneurs. On demand-side alone, India’s corporate sector has to potentially reduce five billion tonnes of CO2 emissions. It is sobering to be reminded of India’s annual CO2 emissions that hover around 5 billion tonnes but India’s global commitment in 2023 is not more than a cumulative one billion tonnes by 2030. The battle is formidable. In 2005, my wife presented me a reprint of Picasso’s Don Quixote and the Windmills which has been hanging above my office table. It serves as a glaring reminder, every morning, of the naiveté and foolishness I represent but I continue to wield my sword to fight the giants.

Harish Borah, a subject expert in climate action and mitigation with 10-plus years of experience, was a QoC-CANSA Fellow 2023. He has been named among the top 25 leading minds in sustainability by The Economic Times, India, and his writing has been tabled at top climate negotiations including at COP28. He was also a part of the ‘2041 Climate Force Antarctica’ crew. Among various engagements, he is the founder of ‘OnePointFive’ collective that focuses on creating a space in India for new climate thinkers to emerge. An alumnus of NIT Silchar, the University of Manchester, and the University of Cambridge, he works as a carbon study/analysis expert for ADW Developments (UK) and serves as a technical advisor to GRIHA and IGBC in India.

Cover photo: CII-Sohrabji Godrej Green Business Centre in Hyderabad. Credit: Facebook