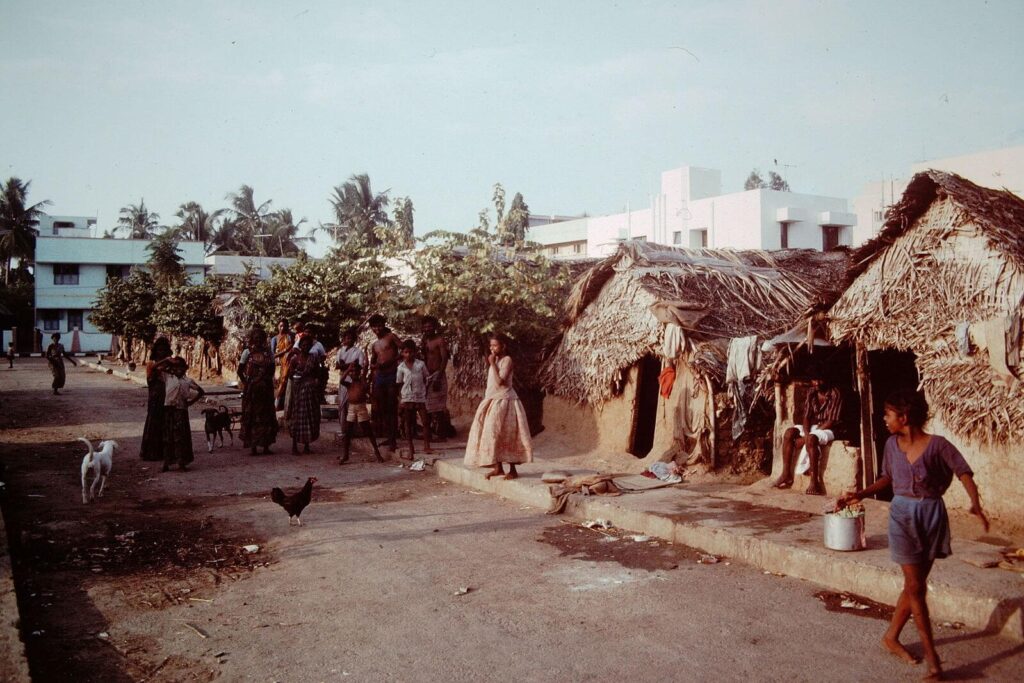

According to the UN, around 100 million people or 24 percent of Indians live in urban slums. And, the number is increasing. People come to cities in search of jobs and a better life. But without affordable housing and basic amenities, they live a life of neglect and struggle for their daily needs every day.

Informal settlements rapidly multiply in cities as there is a lack of adequate low-cost houses. The people, who migrate from other cities – which is more often now because of Climate Change, are left homeless and make the streets or any open space their home. Most big cities are filled with slums, which house the most significant workers of the society — drivers, domestic helps, carpenters, plumbers, cooks and daily wage labourers.

Their daily lives are a struggle for water, food and the fear of eviction. But, they continue living a life in unhygienic conditions without knowing their rights. They are ignored and sidelined by the authorities till its time for elections. They are the vote banks and their significance is realised only during polls.

Here is a compilation of laws, judgments and the housing schemes of the government.

Homelessness and informal settlements

More than 1.8 billion people live in informal settlements or inadequate housing with limited access to essential services such as water and sanitation, electricity and are often under threat of forced eviction. And one of the most severe violations of the right to adequate housing—homelessness—has been on a steep increase in many economically advanced countries.

The right to adequate housing contains freedoms.

These freedoms include:

- Protection against forced evictions[1] and the arbitrary destruction and demolition of one’s home;

- The right to be free from arbitrary interference with one’s home, privacy and family; and

- The right to choose one’s residence, to determine where to live and to freedom of movement.[2]

Those living in informal settlements have limited access to essential services.

Photo: Creative Commons

Landmark judgments

Although there have been progressive judgments in the past years, the slum dwellers continue to face eviction and live in apathy. The famous Olga Telis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation case in 1985 asserted the rights of slum dwellers, most of whom were unaware of this.

When Maharashtra and the Bombay Municipal Corporation in 1981 decided to evict the pavement dwellers and those living in slums in Bombay, it was challenged by the petitioner “on the grounds that it is violative of Articles 19 and 21 of the Constitution”.

The court observed that the right to life conferred by section 21 is vast and far-reaching. It does not simply mean that life can be extinguished or removed only in accordance with the procedure established by law. This is just one aspect of the right to life. The right to livelihood is an equally important aspect of this right because no one can live without means of subsistence… Article 41, which constitutes another guiding principle, stipulates that the State must, within the limits of its economic capacity and its development, effectively guarantee the right to work in the event of unemployment and undeserved desires. The principles set out in Articles 39 (a) and 41 must be considered as equally fundamental for understanding and interpreting the meaning and content of fundamental rights. …The court also held that anyone deprived of their right to a means of subsistence, except in accordance with the just and fair procedure established by law, may challenge deprivation as a violation of the right to life conferred by Article 21.[3]

In 1995, in another important judgement of Chameli Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh, the Supreme Court held that every citizen should have the right to food, water, education and a healthy environment.

The Bench of three Judges of the Supreme Court had considered and held that the right to shelter is a fundamental right available to every citizen and it was read into Article 21 of the Constitution of India as encompassing within its ambit, the right to shelter to make the right to life more meaningful.

The Court observed that:

Shelter for a human being, therefore, is not mere protection of his life and limb. It is however where he has opportunities to grow physically, mentally, intellectually and spiritually. Right to shelter, therefore, includes adequate living space, safe and decent structure, clean and decent surroundings, sufficient light, pure air and water, electricity, sanitation and other civic amenities like roads etc. so as to have easy access to his daily avocation. The right to shelter, therefore, does not mean a mere right to a roof over ones head but right to all the infrastructure necessary to enable them to live and develop as a human being.[4]

In 2010, In Sudama Singh v. Government of Delhi[18] court recognized the relation of human well-being and development with adequate housing by ruling that Adequate housing serves as the crucible for human well-being and development, bringing together elements related to ecology, sustained and sustainable development.[5]

The Delhi’s Shakur Basti case where the slum dwellers were evicted on a cold winter night in December 2015 triggered outrage. No prior notice was given to the residents of jhuggis (shanties). The Delhi Development Authority ruthlessly bulldozed the jhuggis and the residents were unable to gather their belongings.

In this case, the Delhi High Court adopted a restrictive approach towards the issue of rehabilitation, rather than the ‘broad and liberal’ approach. While the Delhi High Court in Shakarpur included lengthy quotes from Ajay Maken and the protocol, but it did not enforce the same… In this case, the Delhi High Court granted limited relief, holding that no demolition could take place without notice, early in the morning or late in the evening, and that a temporary location was to be provided to residents facing demolition so that they weren’t rendered completely shelter-less. The requirement of at least a temporary relocation may yet create more radical possibilities in an otherwise narrow decision.[6]

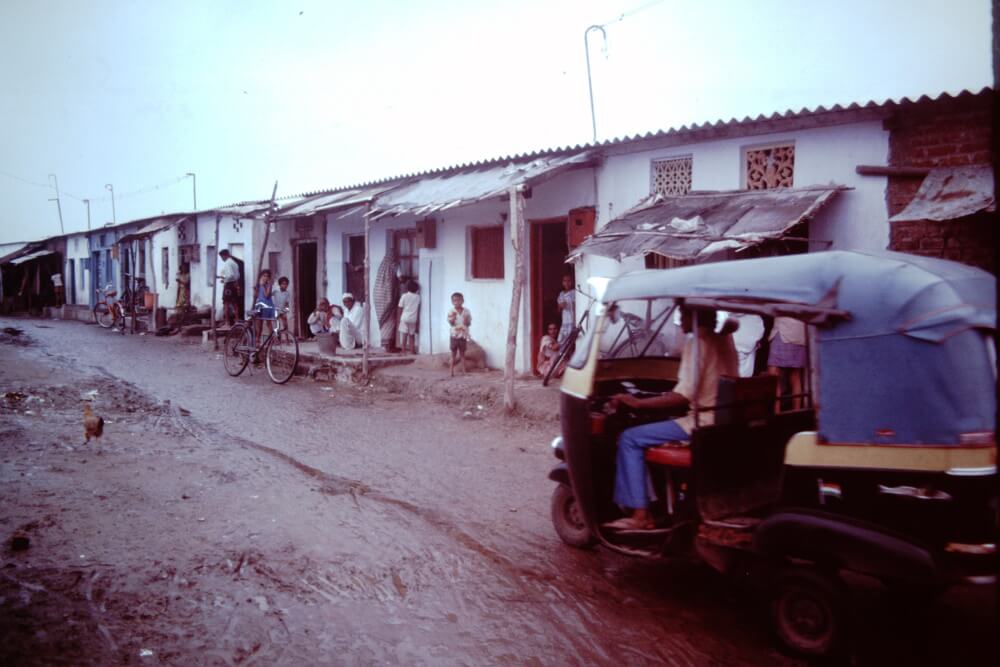

Affordable houses built by Telangana Municipal Administration.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Constitution of India and housing as a right

Housing is not an explicitly stated right in the Constitution of India which is grounded on the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity. It is, however, circumscribed as a part of the Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles of the Constitution.

Housing falls under the following Fundamental Rights guaranteed by the Constitution of India.

Article 21: The right to protection of life and personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.

Article 14: The right of every citizen to be treated equally before the law or be given protection of the laws within the territory of India.

Article 15 (1): The right of every citizen to be protected against any discrimination on grounds of sex, religion, race, caste or place of birth.

Article 19 (1) (d): The right of every citizen to move freely throughout the territory of India.

Article 19 (1) (e): The right of every citizen to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India.

Article 19 (1) (g): The right of every citizen to practise any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business.

The Directive Principles under the ambit of which, the Indian State must formulate policies that provide adequate housing are:

Article 39 (1): State policy to be directed to securing for both men and women equally the right to an adequate means of livelihood.

Article 42: Provisions to be made by the State for securing just and humane conditions of work and for maternity relief.

Article 47: Duty of the State to raise the level of nutrition and the standard of living and to improve public health.[7]

Though the Constitution of India has not specified the right to Housing, the Indian judiciary has, in several rulings made clear people’s right to life to include the right to live with human dignity and bare necessities such as adequate nutrition, clothing and shelter and facilities for reading, writing and expressing oneself in diverse forms, freely moving about and mixing and commingling with fellow human beings.[8]

The rules formulated by the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act of 2016 apply in states like Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Goa, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Tripura, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and West Bengal. Under this act, the real estate promoter is required to declare that they shall not discriminate.[9]

The Smart Cities Mission is one of the major flagship schemes started by the Union government that aims to create inclusive and barrier-free cities for universal access. Manual scavengers, women, persons belonging to Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes/Other Backward Classes, minorities, persons with disabilities and transgender persons are supposed to be given preferential allotment under the PMAY. However, it is said that these schemes do not explicitly prohibit discrimination or provide remedy against the same.[10]

Photo: Creative Commons

Housing for all policy

The Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) is one of the major flagship programmes being implemented by the Bharatiya Janata party-led government. Launched in June 2015 across all Indian states and Union territories, its aim has been to provide all-weather affordable pucca housing for all by 31 March 2022.

To be eligible for the PMAY scheme, applicants must belong to one of the four categories – economically weaker sections (EWS), a low-income group (LIG), a middle-income group I (MIG I), and a middle-income group II (MIG II). The annual household income of the applicant should be within the prescribed limit for each category. Additionally, the applicant must not own a pucca house anywhere in India.[11]

The policy has two verticals: Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Urban) (PMAY-U) for the urban poor and Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana (Rural) (PMAY-G for the rural poor.

PMAY-U is managed by the Housing and Urban Affairs Ministry. It has four verticals, namely, Beneficiary Led Construction (BLC), Affordable Housing in Partnership (AHP), In-Situ Slum Redevelopment (ISSR) and Credit Linked Subsidy Scheme (CLSS). PMAY-U allowed for private sector partnership.

According to a government reply in the Rajya Sabha dated December 12, 2022. Only 61.2 lakh houses out of the sanctioned 1.25 crore houses have been built. This means, in the five and half years since its inception, the policy has been able to fulfil only a little more than half, that is 51 per cent of its target.[12]

In August 2022, PMAY-U was extended up to December 31, 2024. This came after a proposal of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) was accepted the Union Cabinet.[13] However, a study by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) found that between the years 2012 and 2018, urban housing shortage increased by 54 per cent, from 1.88 crore to 2.9 crore.[14] Whether PMAY-U is enough to meet the meets of India’s burgeoning cities remains to be seen.

Cover photo: Kochi; Credit: Creative Commons