Delhi’s municipal governance has long been the site of political contestation and structural reform. From the establishment of the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) in 1958 to its trifurcation in 2012 and subsequent reunification in 2022, the city’s civic administration has undergone repeated reorganisations. Each move has been justified on the grounds of efficiency, decentralisation or financial stability but the story is not as straightforward.

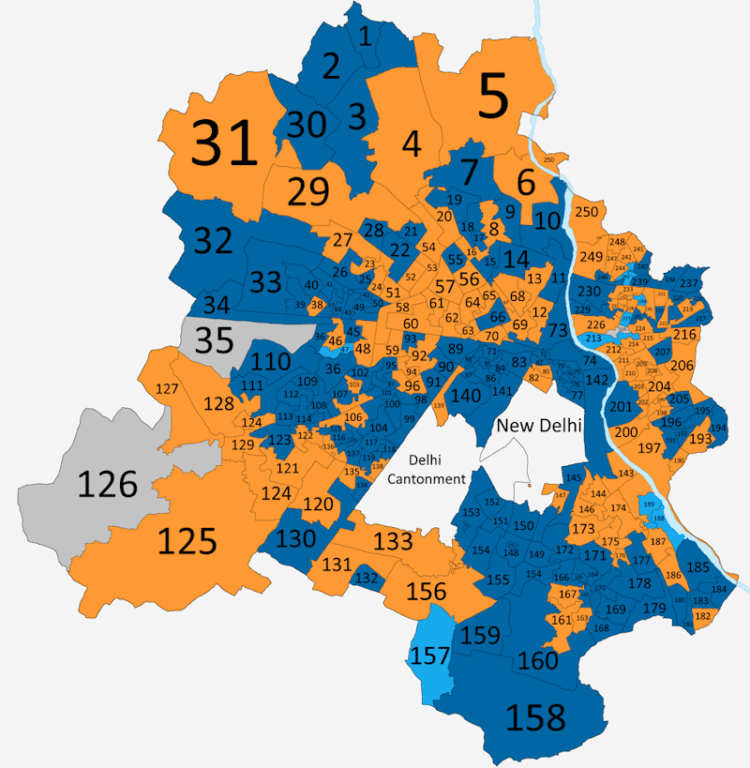

After the reunification or merger in 2022, elections to the MCD were held in December that year for all the 250 wards of the MCD. In this election, the Aam Aadmi Party won the most seats[1] with 132 councillors to the BJP’s 104; the Congress and independents trailed behind. In the by-elections of 2025[2] held for 12 vacant wards, the BJP won seven while AAP secured three, and the Congress and Left parties gained one seat each. Political majority matters to the parties but has little impact on the ground.

Decentralisation has been the buzzword to justify dividing the MCD but even as it finds its way around after the reunification – whither decentralisation now? – the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) has been split[3] into five corporations and placed under the command of the Greater Bengaluru Authority. The Vijayawada Municipal Corporation’s plan[4] to merge nearly 75 gram panchayats into a larger body and the Telangana government’s merger[5] of 27 urban local bodies with the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) all point to experiments in the centralisation-decentralisation of urban governance in India.

However, this chop-and-change resulting in constant redrawing of municipal maps has not necessarily translated[6] into better delivery of services. In fact, a 2024 CAG report[7] notes how, in 18 states, there is a 42 percent gap between resources and expenditure, while only 29 percent of their expenditure has gone into development work. With the elections to the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) wrapped up and Bengaluru heading to civic elections soon[8], we turn our gaze to the Delhi story to assess the impacts of divisions and reunification. Three years after the MCD became one monolith again, questions persist about the impact of the structural change on governance on the ground.

A history of upheavals

The MCD was established in 1958 by an Act of the Parliament. The idea was to create a unified civic body in the national capital to govern the rapidly growing city. Before 2011, the MCD was one of the three civic bodies in the National Capital Territory; the other two were the New Delhi Municipal Council and the Delhi Cantonment Board. The 2011 Delhi Municipal Corporation (Amendment) Act, spearheaded by the then Chief Minister Sheila Dixit, trifurcated[9] the MCD into municipal corporations of North, East, and South Delhi to ensure more efficiency.[10] The NDMC and DCB remained untouched.

Delhi’s municipal governance stands apart from that of other Indian cities because of its status as a national capital, its entity as a state, and the presence of the central government. All of these have significant influences on administrative decisions related to urban governance. Broadly, governance is divided between the central government, the state government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi, and the MCD. The jurisdictions of the Delhi government and the MCD intersect substantially, which have been the issue of contested administrative relationship, as scholars Asha Sarangi and Lipika Ravichandran argue in their essay[11] Decentralization Within Urban Areas in India: A Study of Delhi Metropolitan Governance.

While the MCD is responsible for providing civic services across the largest part of the city, the New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) is entrusted with the governance of specific pockets of New Delhi like the Rashtrapati Bhawan, buildings near the Central Vista, the Parliament House, the Supreme Court complex, North and South Blocks. And the Delhi Cantonment Board (DCB) governs within the cantonment areas and defense establishments.

At its helm, the NDMC has centrally appointed officials and, of course, does not have an elected body. It has a relatively stronger service delivery, benefitting from substantially high fiscal[12] support from the central government. The NDMC ranked[13] seventh in the Swachh Survekshan 2023 ranking. In contrast, the MCD is responsible for civic services for nearly 94 percent of Delhi’s residents but ranked 90th in the cleanliness list – a stark pointer to the difference in services in the same city.

Dixit’s decision was not arbitrary; it relied on multiple expert committees that questioned the effectiveness of a single, large civic body. In 1989, the Balakrishnan Committee[14] was among the first to argue that the unified and unwieldy MCD should be replaced with smaller, more manageable municipal units; in 2001, the Virendra Prakash Committee proposed reorganising[15] it into four municipal corporations and two councils, while a Group of Ministers[16] later recommended the creation of five separate entities. The chip-chop lasted a decade.

In 2022, Delhi’s municipal bodies were brought back[17] under a single civic authority, the reunified MCD. The NDMC and DCB were untouched. The rationale behind the reunification was primarily financial and administrative ease. The Statement of Objects and Reasons of the Bill[18] stated that the 2012 trifurcation failed even though it attempted to improve service delivery; it produced uneven territorial division, creating disparities in resource availability, and weakened the corporation’s financial capacity.

As Sarangi and Ravichandran note, the South Delhi Municipal Corporation due to its richer demographic, had a “greater revenue-generating potential” but this was not the case with the other two municipal bodies. The unification sought to share SDMC’s surplus revenue with the other two. The struggle in other municipal corporations to pay salaries on time to employees, triggering strikes[19] by municipal workers[20] and disruptions in essential civic services prompted the reunification. Municipal finances played a large part here.

Split or reunified – governance is poor

Delhi has never fit neatly into India’s urban governance framework. The three-way division – MCD, NDMC, DCB – usually produced friction. The 2022 Amendment altered this relationship[21] further. In the Act, the word “government” was replaced with “central government” which, in practical terms, sidelines local governments from key aspects of municipal decision-making. It has also raised questions of accountability. Who should citizens hold responsible for civic services delivery?

On the ground, Dharmendra Kumar, secretary of Jan Pahal, a Delhi-based collective of informal workers and low-income families, avers that the MCD merger has not translated into any positive change. “The merger unified the MCD at the top but administrative arrangements at lower levels remain unchanged,” he says, pointing to the Town Vending Committees (TVCs) as an example of how misaligned structures are undermining the policy to provide safe and reasonable hawking zones.

Photo: Ankita Dhar Karmakar

Under the Street Vendors Act (2014)[22], Town Vending Committees were constituted in Delhi with each zone having its own committee. “One TVC was meant to cover 10-14 wards but some zones ended up with two or even three TVCs,” Kumar explains. Despite this, all TVCs were chaired by the same deputy commissioner and the committees rarely functioned independently. “Meetings were always clubbed together, which defeated the purpose of having multiple committees.” Kumar argues that this structural misalignment has been at the core of the problem of hawkers in Delhi. “You cannot create a new parallel structure and expect it to function. TVCs should have been aligned at the level of wards, zones, MLAs, MPs or districts,” he suggests.

From the perspective of the Residents’ Welfare Associations which abound in middle to upper-middle class areas, the reunification of MCD has made little difference to everyday civic life. Atul Goyal, President of United Residents Joint Association (URJA), a network connecting more than 2,500 RWAs across Delhi, says: “On the ground, nothing has really improved.” Their problems in solid waste management, sanitation, and pollution control persist as earlier.

According to him, the reorganisation has not altered how systems function at the neighbourhood level. “You can change the structure at the top but if the earlier practices continue on the streets, people will not see any impact,” Goyal notes. He also flags weak enforcement as a major concern. “There is very little accountability even today. Rules exist but there is no fear of violation,” he says.

In split or reunified municipal corporations, the city’s civic services continue to be awful. In North West Delhi’s Kirari Sharma Enclave[23], water mixed with sewage waste inundates the colony for more than eight months of the year, forcing residents to wade through it with gumboots on. The pothole problem[24] here caused as many as 5,840 casualties in 2023, the highest in five years.

Photo: Ankita Dhar Karmakar

The MCD reportedly[25] saw the highest property tax collected in the last financial year – Rs. 2,700 crore – since the reunification. However, this has not translated into improved services. “Waste management, pollution, and such issues have still not been solved. RWAs are expected to cooperate without adequate tools, support and infrastructure despite residents paying municipal taxes,” points out Goyal.

Although a major reason for the reunification was the fund crisis in the municipal corporations, the reunified MCD, in 2025, continued to face a financial crunch. Its total liabilities increased by over Rs. 2,000 crore[26] since February; the Delhi High Court even directed the Delhi government to look into the MCD’s finances.

A recent report[27] by URJA argues that poor coordination between the Delhi government and the MCD is undermining the city’s efforts to tackle air pollution. Based on more than 160 responses to RTI requests, the study found major gaps in how GRAP[28] is being implemented on ground. The municipal body and the state government have defined roles to address the pollution but these are not functional, the report states, and points to the absence of ward-level and zonal-level teams in most areas despite GRAP’s local rapid-response structure.

Shashi B Pandit, who works with the Dalit Adivasi Shakti Adhikar Manch on rights-based issues including sanitation and manual scavenging, situates the MCD reunification within the larger retreat from decentralised governance. The intent of the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments, he argues, was to bring decision-making closer to citizens and enable their participation which made the trifurcation of the MCD administratively logical. “A city of nearly 15 million people cannot be governed from one place. Greater decentralisation strengthens governance,” he notes.

Pandit is sharply critical of the 2022 reunification which he sees as a move towards centralisation. “There was no collective demand or consultation to bring everything under one authority. This was a political move, not an administrative necessity,” he says. He also questions the use of delayed wages as a justification for the merger. “The unpaid wages were used as a political stunt to discredit the municipal bodies but even now, salaries of waste pickers and sanitation workers employed by the MCD are not consistently credited on time. For municipal workers, the situation remains largely unchanged.”

Since the reunification, protests by municipal workers have not allayed. In 2023, the 3,500 Domestic Breeding Checkers (DBC) went on a five-day strike[29], demanding their regularisation. The following year, MCD’s sanitation workers threatened to sit on a hunger strike[30] if their demands, including regularisation of employment and settlement of outstanding arrears, were not met. In 2025, the MCD’s multi-tasking staff which included DBCs and contractual field workers went on a month-long strike[31] demanding equal pay, medical and earned leave, and permanent jobs.

Challenges that need to be addressed

As things stand, Delhi has seen both models – a large unified body and smaller fragmented bodies – but neither have civic services greatly improved nor have the conditions of workers in the MCD. So what purpose did the reunification serve other than redrawing – somewhat simplifying – Delhi’s municipal map?

Dr Ramanath Jha, distinguished fellow at Observer Research Foundation argues[32] that a single, larger municipal corporation can be better equipped to govern megacities, given its stronger financial and technical capacity. “There can…be greater specialisation among the municipal personnel, which can, in turn, help in the management of megacities,” he writes but also warns that it can negatively impact local self-empowerment. “Larger municipal entities have less incentive to be responsive to local needs,” notes Dr Jha.

In the national capital with multiple power centres, the question is no longer whether Delhi is better off with one municipal corporation or several, but whether urban governance on basic civic services can be improved, be accessible for the majority of people, and bring local government closer to people’s aspirations. Of course, Delhi’s governance is complicated by the presence of the NDMC, the DCB and other central government agencies. Even the creation of municipal bodies, zoning and ward delimitation are in the realm of the central or state governments which, Sarangi and Ravichandran point out, “produces a democratic deficit”.

This means that elected councillors in the MCD – divided or reunified – function within a narrowly defined institutional framework limiting their autonomy and accountability to their voters. For instance, of the 18 functions meant to be devolved to urban local bodies under the 74th Constitutional Amendment, only four lie with the MCD. Does it matter if there’s one MCD or several of them, except from the perspective of political power?

Ankita Dhar Karmakar, Multimedia Journalist and Social Media in-charge in Question of Cities, has reported and written at the intersection of gender, cities, and human rights, among other themes. Her work has been featured in several digital publications, national and international. She is the recipient of the 4th South Asia Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity and the 14th Laadli Media & Advertising Award For Gender Sensitivity. She holds a Master’s degree in English Literature from Ambedkar University, New Delhi

Cover photo: Municipal Corporation of Delhi Civic Center. Credit: Wikimedia Commons